Flushing Waterfront development rendering

When the developers behind Industry City, a massive retail and manufacturing space, announced that they had pulled the plug on their plan to rezone a portion of their property on the Sunset Park waterfront in Brooklyn, community activists in Flushing, Queens celebrated.

The proposed Special Flushing Waterfront District is a planned rezoning to usher in massive development along Flushing Creek, and is now being eyed by both proponents and critics as the next big New York City land use battle. The debate over the Flushing development hits on a number of persistent themes related to housing, development, gentrification, displacement, jobs, and more.

Given the defeat of the Industry City proposal, which had spurred fears of gentrification and displacement in a largely immigrant community, opponents of the Special Flushing Waterfront District appear to have some momentum on their side as the developer’s proposal works its way through the City Planning Commission and to the City Council. Politics in the city have turned decidedly against major development projects pushed by wealthy interests, most notably the aborted Amazon ‘HQ2’ plan for western Queens, which prefaced the Industry City outcome.

“Sunset Park set the tone that predatory rezoning is not acceptable, and communities should be in control,” said Seonae Byeon, the lead housing organizer of the MinKwon Center for Community Action, a tenant advocacy group and one of the most prominent opponents of the Flushing waterfront rezoning. “Whether you live in Brooklyn or Queens, racist rezoning shouldn't be happening in any neighborhoods.”

The proposed project in Flushing, which is itself home to large immigrant communities, would turn 29 acres of the waterfront into a 13-tower luxury complex with retail, hotel, and office spaces, plus over 1,700 residential apartments, 61 of which would have below-market rents deemed affordable.

The plan would also include a public waterfront walkway and outdoor open space. Other benefits cited by the developers — F&T Group, Young Nian Group and United Construction and Development Group, who have formed the consortium, FWRA LLC — include the creation of nearly 3,000 permanent jobs, with an additional 558 average construction workers per day during its building, and clean-up of Flushing Creek. While the project was originally estimated to generate $28 million in annual tax revenue to the city, the developers now say that new economic studies suggest the special waterfront district will generate $164 million in anticipated annual tax revenue.

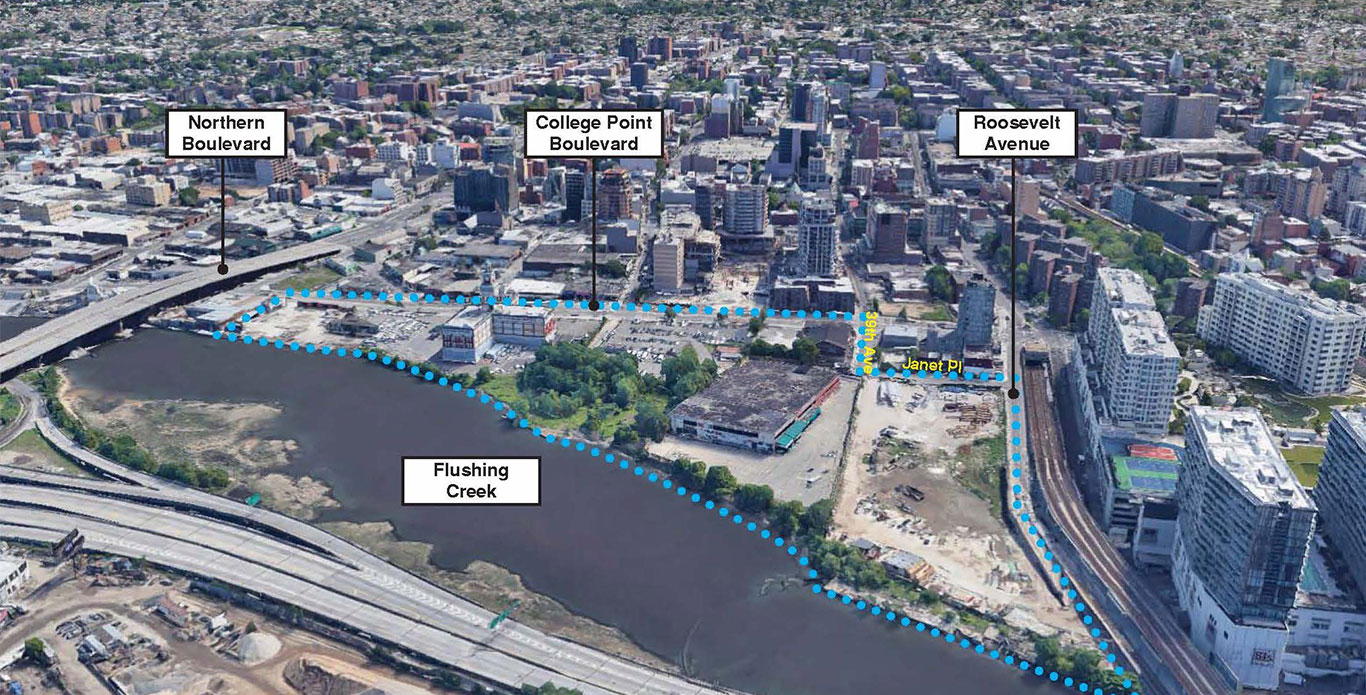

(view of the Flushing site as it currently stands)

(view of the Flushing site as it currently stands)

To realize the developers’ goals, which include removing some zoning restrictions to raise the height of 11 of the proposed towers, they must seek approval from the city, which includes votes by the City Planning Commission, which passed it on Wednesday, and the City Council, as well as other advisory opinions.

But opponents argue the project would fast-track gentrification in the surrounding areas, devastating working-class immigrant residents through rising costs of living and housing displacement. And, more generally, critics argue that it is the wrong type of use of valuable real estate, which they say should have more community-focused purpose with designs by and for the people who live nearby now, with taking on the city’s affordability crisis front and center.

Both the Sunset Park and Flushing rezoning debates are the latest manifestations of the “Vision 2020” Comprehensive Waterfront Plan, which was conceptualized during the Bloomberg administration with the aim of revitalizing New York City’s waterways and waterfront areas. Although the Special Flushing Waterfront District is largely a privately-funded endeavor, public money has underwritten the project since it was originally conceived in 2010, when former Queens Borough President Claire Shulman’s Flushing Willets Point Corona Local Development Corporation (FWC LDF) was granted a $1.5 million Brownfield Opportunity Area (BOA) grant from the Department of State to plan for revitalizing Flusing’s waterfront.

In effect, FWC LDF partnered with the Department of City Planning to develop the proposal called Flushing West, which would’ve rezoned approximately 47 acres of the Flushing waterfront before the plan was withdrawn due to concerns over infrastructure, traffic, affordable housing, and displacement. A somewhat different model of collaboration has distinguished the newly envisioned Special Flushing Waterfront District and rezoning application, namely when Community Board 7 Vice Chair Chuck Apelian served as a consultant to the developers before recusing himself from the rezoning vote.

But activists in Flushing say that, among other examples, both the opposition to Industry City’s proposed expansion and to the Flushing special district are proof of a growing movement for community-led rezoning efforts, in which New Yorkers refuse to be taken advantage of by monied developers. Through extensive coalition-building across the city, activists say they are pushing back against the status quo of the city’s land use processes to galvanize change that will put communities’ voices first.

The City Planning Commission, a body made up of appointees of city elected officials, voted to approve the rezoning application on Wednesday, sending it to the City Council for consideration, with 50 days for a vote by the Council. In the meantime, negotiations between the developer and local City Council Member Peter Koo are expected to unfold in both public and private, including through a Council zoning committee hearing on the proposal.

While other elected officials in Flushing have voiced their disapproval of the waterfront project, Council Member Koo has not taken an official stance one way or the other. He hinted at his opinion in a statement to Gotham Gazette, saying, “The Special Flushing Waterfront District has many merits that would provide our community with tangible benefits we wouldn't have under an as-of-right scenario. We're working with stakeholders in hopes of making this project the best it can be for Flushing.”

The Flushing waterfront rezoning plan has been divisive since the developers submitted their application in December 2019, with opponents arguing in part that environmental remediation and affordable housing should not be dependent upon the interests of private real estate. When the Department of City Planning certified the waterfront project without an Environmental Assessment Statement on the basis the rezoning would not result in significant impacts, effectively bypassing initial community input, critics said the city exploited the inherent weaknesses of the land use review process, known as ULURP, to rush the rezoning application despite the needs of Flushing residents.

The move emboldened a trio of groups — Chhaya Community Development Corporation, the Greater Flushing Chamber of Commerce, and the MinKwon Center — to file a lawsuit against the Department of City Planning and the City Planning Commission, calling for an environmental review of the development proposal and ultimately more community involvement in the waterfront project.

“There are lots of questions about the impact of this particular project that we will never find out because the city has rubber-stamped the developers’ rationale that there is not enough of an environmental impact,” said John Choe, executive director of the Greater Flushing Chamber of Commerce and a Democatic candidate running to replace the term-limited Koo via next year’s city elections.

Activists have also expressed doubt concerning ULURP’s ability to empower community voices after the City Planning Commission’s first land use hearing in six months was held virtually due to the coronavirus pandemic, on September 16.

“Having a public hearing [online] in a district where 41% of people don't have broadband internet access is not a public hearing,” said Elizabeth Oh, a community organizer with Flushing Anti-Displacement Alliance, citing data from City Comptroller Scott Stringer’s office. On the day of the hearing, Byeon decried on Twitter, “Our First Amendment rights are violated.”

Not unlike Industry City’s 11-hour City Council hearing, the City Planning Commission’s public hearing for the Flushing waterfront rezoning went on for over six hours. Some criticized the developer’s presentation at the start of the hearing for being too long and taking time away from community members’ testimonials. The expected City Council hearing on the Flushing proposal will likely also be a long, contentious affair.

On the other side of the debate, the collapse of the Industry City rezoning proposal coupled with the immense economic stress of the coronavirus recession has only heightened the sense of urgency surrounding the Flushing waterfront project. Carlo Scissura, the president and CEO of the New York Building Congress and a supporter of the Flushing development plan, objects to opponents’ claims that such major development won’t address the community's needs in the midst of a pandemic. “This is exactly what we should be doing when we’re in a crisis,” he said in an interview. “We need to invest.”

How and where to invest is, of course, precisely the crux of community members’ concerns, but, according to Scissura, “There will be opportunity at the community board, borough, and City Council levels to shape the project moving forward.”

Unemployment in Queens spiked from 3% in February to 15.1% in April, at the height of the pandemic, according to data from New York’s Department of Labor. The rate was down slightly in September, but remained high at 13.8%.

In zip code 11354, where the Flushing waterfront land to be rezoned is located, the percent change in unemployment is even more extreme. Data from The New York Times shows that the unemployment rate in the neighborhood in February was a mere 2%. In June, the estimated unemployment rate jumped to 23%, with other parts of the area as high as 28%.

Several proponents of the project have voiced anxiety about growing, blanket antagonism toward development in the city, a political climate that Tom Grech, head of the Queens Chamber of Commerce, has characterized as “the environment of ‘no.’” As the city lags behind the country in terms of a coronavirus-related fiscal recovery, Grech argues, “We should be rolling out the red carpet for people who go through the proper channels to create investment opportunities.”

In a statement to Gotham Gazette, the consortium of developers behind the Flushing waterfront project, FWRA, LLC, likewise attributed the failure of Industry City to a misguided anti-development ideology.

“Industry City was yet another example of politics over people,” the statement reads. “The Special Flushing Waterfront District is an entirely different project, the biggest difference of which is our District is NOT A REZONING. We are not asking for additional density except where affordable housing will be provided. We have been working with the community and its stakeholders for years on this project, including the opposition. Flushing's waterfront has been a contaminated wasteland for decades. Without development, there is no progress or growth. Can we for once put politics aside and prioritize the residents of Flushing?”

Grech asked of the project’s opponents, “What is your alternative? What do you suggest instead of the developers’ money?”

Ideally, Flushing activists say they would like to put forth their own community-developed plan for revitalizing the waterfront, as organizers in Industry City did. But that plan does not yet exist, and the organized effort to create it is in development.

While Industry City rezoning negotiations were also ongoing for years, public debate intensified greatly when the proposal entered ULURP, was passed by the City Planning Commission, and hit the City Council countdown clock. Pushed by organized local activists, Sunset Park Council Member Carlos Menchaca decided to oppose the rezoning altogether, even after many of his earlier demands had been met by the developers. With some of his colleagues in the Council expressing support for the proposal because of its promise of thousands of additional jobs, Menchaca rallied many other Brooklyn elected officials against it over fears of displacement and what they saw as too-few community benefits, leading the developer to pull the plan.

While Council Member Koo appears open to considering the Special Flushing Waterfront District proposal and negotiations appear set to enter a new stage given the ULURP process, Queens Borough President Sharon Lee has recommended to reject the proposal, and local State Assembly Member Ron Kim has also voiced his disapproval of the plan. Lee’s likely successor, Donovan Richards, has not taken a public stance on the project, but he recently voiced his support for the proposed YourLIC development plan along Long Island City’s waterfront. State Senators Toby Stavisky and John Liu have expressed public enthusiasm for the waterfront rezoning. Mayor Bill de Blasio has not addressed the issue at all, just as he also didn’t take a position on the Industry City proposal, saying it was a private application, not city-backed, and that while the promise of jobs was intriguing he wanted to let the City Council process play out, which it then did to the proposal’s demise.

Some believe that one of the reasons why the rezoning project in Flushing has flown “below the radar” of politicians is the ethnicity of the transnational developer team, whose members are Chinese- and Taiwanese-American. “If this was a group of white developers, displacing African Americans, Latinos, people would be paying a lot more attention to what's going on here,” said Choe. “But because it's Chinese-American developers pushing out Chinese-American residents and small business owners, no one seems to be paying attention to what is a very similar situation as other neighborhoods that have been gentrified.”

Proponents of the project have emphasized at public hearings that the developers are members of Flushing who want to empower the community. However, Dr. Tarry Hum, professor and chair of Urban Studies at Queens College, argues that this wrongly conflates transnational affluent developers with Flushing’s marginalized groups, such as immigrants and small business owners, who are more likely to experience displacement as a result of gentrification.

“When [the developers] say they’re from the community, you have to wonder which community they’re talking about,” said Hum, who has long questioned the proposed redevelopment.

While organizers in Sunset Park had necessary time — seven years — to develop a comprehensive alternative vision to their waterfront rezoning, activists in Flushing say they do not have that luxury. “This rezoning plan just hit us like a bomb that’s already lighted,” said Byeon.

For now, local groups say they are collaborating closely to develop an alternative plan to the developers’ that reflects the needs of the community.

Not only that, they’re in contact with organizers and groups in other neighborhoods, including those in Sunset Park, Long Island City, and Inwood, as part of a larger effort to form a city-wide coalition. During a time when the coronavirus has created a broader sense of isolation in the city, Flushing activists say they are grateful for the solidarity and empathy found in these other communities. What’s more, activists say that the increased reliance on technology during the pandemic has better enabled community-led planning across a larger, geographic scope.

The ULURP process has “forced people to fight for concessions from the developers and sell off communities bit by bit,” said Sarah Ahn, an organizer with Flushing Workers Center. Activists hope that their alliance will function as a network for those experiencing unwanted rezoning to share strategies and build power against the prevailing system.

No matter what vision plan the opposition drafts, however, the Flushing project’s developers are adamant that only one of two options is possible: the currently proposed mixed-use development, including public waterfront and open space access, as well as affordable housing, or an “as-of-right” development without any public benefits. Critics have cast some doubt on whether the developers can build as of right.

To this, Choe suggested a simple solution: “Let’s call their bluff.”

***

by Allison Smith for Gotham Gazette

@allison_n_smith @GothamGazette

Note: this article has been updated with the latest tax revenue projections by the developers and to note that the developer team is both Chinese- and Taiwanese-American.