More Evidence Punitive NYPD Youth Programs Fail

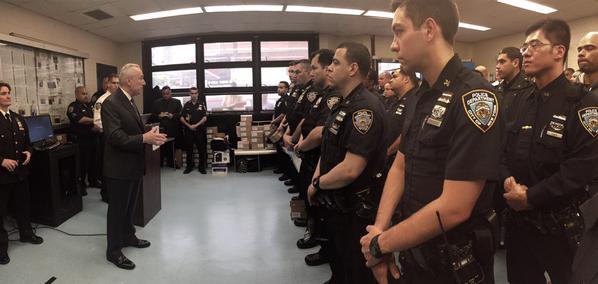

(photo via @NYPDnews)

This week the New York Times revealed the content of an internal NYPD report showing that a much lauded juvenile crime program doesn’t work. It’s yet another example of misguided punitive policing, offering little by way of actual progress.

Originally developed under the title “Juvenile Robbery Intervention Program” (J-RIP), it targets past juvenile offenders in hopes of preventing future crime. The original J-RIP program, which began in Brownsville in 2007 and expanded to East Harlem in 2009, targeted juvenile robbery offenders who were back in the community. These youths were given a clear message that they were under enhanced police supervision and would face significant consequences if rearrested. They were also offered mentoring and a few support services by police in hopes of steering them in the right direction.

In practice, the program offered little in the way of services. Young people were given a chance to participate in existing programs like the Police Athletic League (PAL) and were regularly visited by uniformed officers in their homes and on the streets. While these officers were supposed to be acting as mentors and monitors, defense lawyers reported that officers sometimes used these visits as a pretext to conduct searches and that they sometimes called attention to program relationships in front of other youth, potentially marking them as informants—a dangerous label in these neighborhoods.

No real services, such as job placement or family counseling were provided, and the officers involved had no special social services training, playing a primarily surveillance and enforcement role.

In April of 2014, NYPD Chief Joanne Jaffe, who developed the program, spoke at the Center for New York City Affairs at the New School, where she lauded J-RIP as being highly effective. She provided data that showed that over the course of the program robberies in the targeted areas had fallen significantly. What she did not discuss, but the November 2014 NYPD evaluation report makes clear, is that the decline mirrored city-wide trends and that J-RIP participants were rearrested at the same or higher rates than youth with similar records in the same and nearby neighborhoods without J-RIP.

Even though the 2014 report showed there were no crime reductions under J-RIP, the NYPD has moved forward with an expansion of the program in a different guise.

In early 2015, the NYPD rolled out NYC Ceasefire, under the leadership of Susan Herman, Deputy Commissioner for Collaborative Policing. The new version focuses more on gun crimes and adds group “call-in” meetings in which the targeted youth are brought in and lectured by police and community members about the harmful effects of their violent actions and the potential enhanced consequences of additional violent offenses. They are then placed under extensive surveillance regimes and targeted for enhanced punishments if caught re-offending. They are also offered some minimal services, primarily in the form of a centralized referral phone number run by a local non-profit that is there to link young people to already existing programs.

J-RIP and NYC Ceasefire are both examples of “Focused Deterrence” programs. Developed by criminologist David Kennedy, and first implemented in Boston in 1996, they attempt to stop gun violence or other serious crime through intensive and targeted enforcement combined with support services.

Ideally this model begins with a community mobilization effort in partnership with local police. The goal is to send a unified message to young people that serious crime will no longer be tolerated. If it occurs, they will use every resource at their disposal (“pulling levers”) to not only apprehend the assailant but to disrupt the street life of young people involved in crime across the board. The hope is that young people will choose to avoid violence so that they can concentrate on socializing and low level criminality free of constant police harassment. This is based on research that showed that a great deal of shooting was not drug or robbery related but involved a constant tit for tat of revenge gunfire by rival factions of young people engaged primarily in turf battles.

The key is to break that cycle of retribution and gun carrying. To achieve this, young people believed to be involved in violence are called into meetings with local police and community leaders and threatened with intensive surveillance and enforcement if the gun violence doesn’t stop. These “call ins” are made possible in part because many of these young people are on probation or parole for past offenses.

In addition to more intensive enforcement efforts, there is usually an effort to develop some targeted social services with the hope that this will help draw some of these young people away from violence and towards education and employment opportunities.

This approach relies primarily on intensive punitive enforcement efforts such as surveillance, investigations, arrests, and intensified prosecutions. Also, the social services offered tend to be very thin, involving some counseling and recreational opportunities but rarely access to actual jobs or advanced educational placements.

Some youth are able to get GEDs and access some social programs, but very few wind up with jobs, much less well-paying or stable ones. In some cases the focus is on a variety of life skills and socialization classes which do nothing to create real opportunities for people and reinforce the ethos of personal responsibility that often ends up blaming the victim for their unemployment and educational failure in a community that tends to be incredibly poor, underserved, segregated, and dangerous.

Evaluation research of these programs does show some meaningful declines in crime that can even last for years. Overall, though, the results are quite thin. Most reductions are small, occur in only a few crime categories, and don’t last very long. They also continue to reinforce a punitive mindset about how to deal with young people in high crime, high poverty communities, most of whom are not white.

It is certainly true that violent crime is heavily concentrated among a fairly small population of young people in specific neighborhoods. It makes more sense to target them than indiscriminately stopping and frisking or arresting and summonsing hundreds of thousands of young people who have either done nothing wrong or engaged in minor misbehavior. Despite the claims of the Broken Windows theory, there really isn’t a strong connection between the two groups.

The problem lies not in the targeting, but in the methods used. Most young people who engage in serious criminality are already living in harsh and dangerous circumstances. They are fearful of other youth, abusive family members, and the prospect of a future of joblessness and poverty. They don’t need more threats and punishment in their lives.

They need stability, positive guidance, and real pathways out of poverty. This requires a long-term commitment to their well-being, not a telephone referral and home visits by the same people who arrest and harass them and their friends on the streets. It was Bill Bratton, in his first stint as NYPD commissioner, who pointed out that police officers are not social workers, they’re not trained for it, nor prepared for it, and that’s not their role. Why would they be the best-suited for engaging these young people as mentors or life skills trainers? They aren’t.

It makes much more sense to do two types of things.

First, we have to have a real conversation about entrenched racialized poverty concentrated in highly-segregated neighborhoods. These are the neighborhoods that continue to be the main source of violent crime problems. It is true that crime has declined overall without major reductions in poverty or segregation, but it’s also true that the crime that remains is concentrated in these areas. And, unlike aggressive policing and mass incarceration, doing something about racialized poverty and exclusion would have general benefits for society in terms of reducing poverty, inequality, and racial injustice.

Second, we need to use peer-based mentoring systems and outreach workers, who can talk to people from a shared position of living in one of these neighborhoods. The power of that connection for building credibility cannot be overstated. Recently, Mayor de Blasio has expanded a number of City Council-developed initiatives to use violence interrupters and other community-based and public health-oriented interventions to reduce gun violence.

So-called “cure violence” programs like SOS Crown Heights, and GMACC in East Flatbush are training young adults to break the cycle of violence through rumor control, gang truces, and ongoing engagement with youth out on the streets. They provide safe spaces for young people to talk out their problems and when well-funded, provide real services to them and their families to deal with problems of housing, education, and unemployment, as well as mental illness and substance abuse.

It’s time for Mayor de Blasio and the NYPD to abandon NYC Ceasefire and other focused deterrence initiatives that primarily criminalize young people. We already know that jails and prisons produce much worse life outcomes for these youth. Let’s stop relying on coercion and control and try more compassion and concern.

***

Alex S. Vitale is associate professor of sociology at Brooklyn College and author of City of Disorder: How the Quality of Life Campaign Transformed New York Politics. He is senior policy adviser to the Police Reform Organizing Project and serves on the New York State Advisory Committee to the US Civil Rights Commission. You can follow him on Twitter: @avitale

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Time for the Mayor and the Governor to Work Together

De Blasio and Cuomo, via the Governor's Office

They are elected to lead millions of people, to handle billions of taxpayer dollars, and to develop effective public policy. To be as effective as possible, they must work together.

Yet, they barely speak to each other and won't even say each other's name in public.

There is simply no way that the ongoing feud between Governor Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio isn't hurting New Yorkers. The behavior of the two men - New York City's top two elected leaders - is beneath the esteem of their offices.

A leading advocate, Mary Brosnahan of Coalition for the Homeless, put it perfectly in an interview with Politico New York: "They're both very smart people, let's just lower the testosterone and ramp up the cooperation. It just kills me to see homeless New Yorkers being played like pawns in the middle of it."

Lately, it has been homeless people as pawns, but it has been all New Yorkers at some point over the past two years.

Sure, the feud can be the source of fun for observers, even for the governor and his team, it seems. But, there are legitimate policy issues, livelihoods, and lives at stake. It's well past time for Cuomo and de Blasio to work together more closely. And there are steps, beyond the recent dinner they shared, that can easily be taken - if they care enough to try.

The already toxic relationship took a turn for the worse when, in a now-infamous airing of grievances, de Blasio criticized the governor to the press at length on June 30. Remarkable for several reasons, de Blasio's words seemed to indicate he was giving up on the prospects of a strong working relationship with his former boss and longtime friend.

Still, in November, Cuomo defied what observers were seeing when he said, "The relationship is good...This is a professional relationship."

The governor added what appears to be nothing short of a lie, saying: "We coordinate the best we can."

Perhaps Cuomo's statement was true if by "can" he was implying 'given the fact that we are both more concerned with our petty feud than with working for the people of New York.'

When it has come to a series of issues: Ebola, the MTA, Legionnaires' Disease, homelessness, and more, the city and state have clearly not been coordinating "the best" they could.

Of course members of the two administrations talk with each other all the time and coordinate on a variety of public policy matters - there are major day-to-day operations that necessitate this. But, it is abundantly clear that the collaboration is not as strong as it could or should be.

Beyond beginning to speak more regularly by phone and in person, de Blasio and Cuomo could start regularly appearing at events together. Giving the semblance of a working relationship would at least instill more confidence that the two leaders have one and are not being negligent. A little bit of casual conversation, as the two had while awaiting the Pope in September, can only help repair the relationship.

Cuomo and de Blasio don't have to immediately hold joint announcements, they could simply share space when they're due to speak at the same event, something it appears they've avoided with intent.

But, they could hold joint events immediately and start to move beyond The Feud. De Blasio is set to make a minimum wage announcement Wednesday - Cuomo should be there and have a speaking role. Then, de Blasio should be similarly welcomed to Cuomo's next minimum wage rally in the city (he's been conspicuously absent from several). Also Wednesday, Cuomo is expected to announce a renovation plan for Penn Station - de Blasio should be there, not absent like he was when Cuomo announced plans for a new LaGaurdia Airport.

The two Wednesday events are, of course, scheduled for the same time: 2 p.m.

On Thursday, de Blasio is set to sign an executive order mandating paid parental leave for some city employees. Cuomo should be there, too, and he should use the occasion to praise the mayor and explain his intention to push a statewide paid family leave policy.

Though they have very different styles and somewhat different political philosophies, Cuomo and de Blasio actually agree on quite a bit and could find many ways to truly work together. The two should soon hold a joint announcement after coming to a New York/New York IV supportive housing deal.

They missed a good opportunity to show a united front when they came to an agreement on MTA capital plan funding in October after a prolonged and too-public dispute.

But, as they go down a similar road on homelessness, wouldn't it be refreshing if early in the new year Cuomo and de Blasio could coordinate policy and hold a joint press conference to explain how they are going to work together to improve shelter conditions, get people off the streets and into housing, and keep people from becoming homeless in the first place?

Like you, I am not holding my breath for such an announcement or for any of the joint appearances outlined above.

As the New York Times editorial board wrote in late November, "In a better world, the mayor and governor would be mutually supportive allies working together to ease the suffering of tens of thousands of homeless residents of the state's most important city. But in reality, the two men are stuck in a malfunctioning relationship that has turned once-routine city-state partnerships and problem-solving exercises into an unusually fraught psychodrama."

On Monday, the mayor was faced with a barrage of questions from reporters about the homelessness-related executive order the governor had issued with little warning to the de Blasio administration. It has become something of a pattern, state action without coordinating with the city, the governor showing the mayor who is in charge.

"We are very willing to work with the state," de Blasio said in response to a question about why he and his old colleague couldn't simply get together and hash out joint homelessness policy.

Being willing to work together is very different, obviously, from proactively seeking opportunities to mend fences and move forward for the good of the people of the city and state.

***

by Ben Max, Gotham Gazette

@tweetBenMax

Ending the Revolving Door of Homelessness

Patricia Swann, the author

While Mayor Bill de Blasio works on the details of a 15-year, $2.6 billion supportive housing program to address homelessness, Gov. Andrew Cuomo is creating a statewide plan to reduce homelessness. New York should draw on approaches that have helped in the past as well as those that seem promising, especially supportive housing, which offers job training, debt counseling, mental health care, and other crucial services to residents in an effort to stop the revolving door of homelessness.

We all have to start by acknowledging reality: homelessness is a chronic New York problem, as we can tell from walking the streets or reviewing simple statistics. On any given night the number of people sleeping in shelters is close to 60,000 -- 25,000 are children.

New Yorkers fatigued by the crisis tend to identify it with street dwellers – often middle-aged men with substance-abuse or mental health issues. The truth is that homelessness is rising among families, younger men and women, and the working poor.

The one-two punch keeps getting worse: housing costs are exorbitant while wages are stagnant. Last year, 30.1 percent of the city’s renters paid more than half their incomes in rent. The result: New York City saw 26,857 evictions in 2014.

So much for de-stigmatizing homelessness — the reality is that these are our neighbors and coworkers.

The urgent question is, what works?

In the past 20 years, the New York Community Trust has given about $30 million to nonprofits addressing different aspects of the problem. One proven approach is not simply to increase shelters but to create permanent supportive housing for lower-income New Yorkers. That includes on-site services for medical and physical disabilities, HIV-related illnesses, and mental and substance-abuse disorders. This housing should coordinate with nearby groups that provide other basics, including childhood education centers, employment and financial training, health and substance-abuse clinics, open spaces, access to quality food, libraries and cultural venues.

Studies show such supportive housing cuts taxpayer costs while helping vulnerable people become productive citizens. In the past, the state and city split the cost of supportive housing as well as stronger protections for existing low-cost housing; we hope they will resume that agreement.

Still, it takes years for new units to come online, and meanwhile nearly 60,000 people subsist in shelters that the city’s Department of Investigation calls dilapidated. We need to test alternate strategies. That’s why the Trust is funding an initiative called Gateway Housing, a coalition of nonprofits that run city shelters. Under Gateway, the nonprofits are committed to working with the city and state to rebuild shelters.

More important, they’ll use proven practices and undergo regular evaluations of their social-services programs. Because a strong community is critical to addressing homelessness, Gateway seeks to make shelters integral to neighborhoods.

We have learned that well-directed money can deliver lasting results. For example, we’ve funded several groups that had success in assisting families deal with rising housing costs — by freezing rents for the elderly and disabled, or by providing emergency aid and financial counseling to low-wage New Yorkers. Many times, a head of family who loses a job or is dealing with a health crisis needs just a few weeks’ aid to avoid eviction.

The Trust also funds a promising initiative called Joint-Ownership Entity. Under that model, nonprofit developers — the same organizations that saved the South Bronx, eastern and central Brooklyn, and northern Manhattan from disappearing into rubble in the late seventies — are combining developments into single-ownership entities. This should help them achieve economies of scale in running and maintaining their properties, keep rents down, and generate revenue for services. These nonprofit developers are important neighborhood anchors; if not for the housing they manage at affordable rents, many of the residents would become homeless.

We’re not naïve: No one can end homelessness in an expensive city with persistent pockets of poverty. But by finding ways to keep rents affordable in some neighborhoods, supporting those facing temporary financial setbacks, and offering job training, substance-abuse counseling, and other wraparound services, we can buttress thousands of New Yorkers who are trying to provide a stable home to their families.

***

Patricia A. Swann is a Senior Program Officer for Community Development at the New York Community Trust. On Twitter @NYCommTrust.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.