Parades, Permits And The Right To Protest

The New York Police Department has published a rule that could end the long-held and cherished right of protesters to proceed down the sidewalks of New York. It also imposes restrictions on two or more vehicles or bicycles “proceeding together.” A hearing is scheduled for Police Plaza at 6 PM on Wednesday, August 23 on the proposed rule, which would be put into place by “the authority vested in the Police Commissioner” rather than through local law. [Update August 21: The police department has withdrawn some of its proposed rules, and the August 23 hearing has been cancelled]

The rule has drawn the ire of civil liberties organizations. When civil rights activists led by the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. could not get permits for marches through the streets of the segregationist South in the 1950s and 1960s, they resorted to staying on public sidewalks, observing traffic lights at corners, and being careful not to interfere with pedestrian traffic. Even then they could run afoul of racist police forces, but at least the courts held that the protestors were within their rights.

Permits are required for marching through the streets or assembling in the public parks of New York, a right that has become increasingly restricted in the last decade or so. Whenever a protest group didn’t have time to get a permit--especially for a small demonstration--it was able to assemble and march on the sidewalk as long as it did not impede traffic.

The other provisions of the proposed rule, quietly made public on July 18, are aimed squarely at the long-running dispute between the police and Critical Mass, the bicyclists group that has been organizing group bike rides through the streets of New York on Friday nights as a combination of outing and protest. More than 260 of these bicyclists were arrested during protests at the Republican National Convention in New York in 2004.

Under the proposed rule, any “procession or race” of 20 or more vehicles, bicycles, or “herded animals” on a public street or sidewalk will require a parade permit. Moreover, two or more pedestrians, vehicles, or animals in a “procession or race” that fail to comply with traffic rules--already a violation--would be able to be charged with parading without a permit.

Clyde Haberman, in his New York Times column wrote, “Be honest. Have you never, while strolling or biking with a companion, crossed the street against a red light? It would seem that the two of you will now, technically speaking, qualify as a parade. And since you probably will not have first asked the police for a parade permit, it appears that you will--again technically--be breaking two laws. What happened here is that a molehill became a mountain.”

Norman Siegel, the civil rights attorney who represents Critical Mass, told Associated Press, “If the rules were adopted, New Yorkers will need the government’s permission to exercise their First Amendment rights, and that’s totally unacceptable.” Police Department Deputy Commissioner Paul Browne countered that opponents of the new rules are “grasping at unrealistic scenarios.”

Ann Northrop, a veteran organizer of scores of protests for the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), said, “The cops feel that they must always be in control and they live in fear of losing control and anarchy breaking out. They therefore go overboard to try to shut down everybody’s freedom of movement. They really believe in and want a police state and Giuliani and Bloomberg--and even Dinkins--have been more than happy to accommodate their approach.”

Police Commissioner Kelly, in an op-ed piece in the New York Post called “Protests & the NYPD: Keeping Speech Free and Safe,” said that the department is responding to a ruling by Justice Michael Stallman in the Critical Mass case that parade rules in the city were too vague. Kelly wrote, “None of the clarifications {in the proposed rule] in any way impinge on free speech or the message behind a march, parade, or protest. They impose no new penalties or punishments, and are in complete conformity with the conceptual framework of existing law.” He noted that the bicycle protests constituted “a real public safety problem” and had to be addressed.

“Every day,” Kelly wrote, “the department performs the great juggling act of accommodating street fairs, protests, parades and performances of one sort or another - while also safeguarding the participants and the public, and without letting the rest of the city grind to a halt.”

While mayors and police commissioners always say that they are acting to protect public safety and uphold the First Amendment, a federal lawsuit against Mayor Bloomberg brought by protesters at the Republican Convention in 2004 has revealed that his motivations may have really been political. Court documents in the case reveal, according to NY-1 News, that “an internal email a city parks official wrote back in 2004 says: â€It is very important that we do not permit any big or political events for the period between August 23 and September 6, 2004....It's really important for us to keep track of any large events (over 1,000 people), and any rallies or events that seem sensitive or political in nature.’” The New York Sun headline said, “’Mike’s Re-Election’ Concern Stopped Park Concert.”

Bloomberg denied knowledge of the groups that were denied permits, but the Times reported, “Mr. Bloomberg's involvement in the deliberations over the protests may have been different from how he and his aides have portrayed it.”

The suit was brought by the National Council of Arab Americans and the ANSWER Coalition, which had sought to rally on the Great Lawn of Central Park. It was blocked by courts, which agreed with the “security” concerns of the police.

The city is also having to pay out millions of dollars in settlements to the protestors police wrongfully arrested or detained during the Republican Convention.

City Council Speaker Christine Quinn issued a statement on July 20 saying, “These proposals raise significant questions that we are examining carefully.” No word as of this writing what action the council will take if the police department does not address Quinn’s concerns such as whether the rule constitutes “too broad a definition of a parade” and First Amendment concerns. Manhattan Councilmember Alan Gerson told the Times, “Let us remember that part of the right to protest is the right to spontaneously protest.”

Chris Dunn, associate legal director for the New York Civil Liberties Union, told Gotham Gazette, “It is quite likely that the rule will not be adopted in its present form. The police department can adopt a different rule or no rule at all.” He stressed that while the rule doesn’t restrict the right of assembly, “a family of four that doesn’t stop at a traffic light could be arrested.”

“The last thing the police department needs is to have to negotiate every funeral procession or class trip,” Dunn said. “They have better things to do.” He noted that the permit process can be arduous and take months.

The civil liberties union is in talks with the police department to get the rule modified or dropped and with the city council in case the negotiations with the police fail. “The Police Department is trying to rewrite the rules on permits,” Dunn said. “That’s the council’s responsibility.” If neither the police nor the council addresses the First Amendment concerns, Dunn’s group is prepared to go to court over it.

Noah Brudnick, deputy director for advocacy at Transportation Alternatives, a group that advocates for “better bicycling, walking, and public transit, and fewer cars,” in a city notably hostile to them, said the rule would “deter New Yorkers from walking and riding bikes” because it would make it “much more difficult for recreational clubs to organize runs, jogs and bike rides.” He also said the potential restrictions on walking tours and sightseeing “would hurt the economy of the city.”

Brudnick’s group, too, is working with the council on alternatives to the new police rule and mobilizing for the public hearing at the Police Department on August 23.

City Prevails in Suit Challenging Right to Inspect Bags on Subways

The Second Circuit Court of Appeals, a federal court, ruled unanimously on August 25 that the city had the right to randomly inspect bags being carried into the subways. Judge Chester Straub wrote, “We will not—and may not—second-guess the minutiae” of the decisions made by city counter-terrorism experts and elected officials who have “undertaken the delicate and esoteric task of deciding how best to marshal their available resources.” City Corporation Counsel said that the court agreed that the inspection program “balanced subway security and civil liberties.” Police Commissioner Kelly said, “Common sense prevailed.”

The inspections were begun last July after the London subway system was attacked by terrorists with bombs, killing more than 50 people. While the police have retained the right to inspect bags, the inspections have been much less evident in recent months. People trying to enter the subway retained the right to exit the station without submitting to an inspection, but they could not board trains.

The New York Civil Liberties Union had argued that the “unprecedented search program is not sufficiently effective to justify subjecting the millions of daily subway riders to suspicionless police searches. The NYCLU therefore has asked the courts to halt the program as violation of the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution.”

Andy Humm, a former member of the City Commission on Human Rights, has been in charge of the civil rights topic page since its inception in 2001. He is co-host of the weekly "Gay USA" on Manhattan Neighborhood Network (34 on Time-Warner; 107 on RCN) on Thursdays at 11 PM. Â

Gay Marriage Ruling Highlights a Changing Court

The 4-2 decisionof the New York State Court of Appeals denying that same-sex couples have a constitutional right to marry was more than just a blow to the gay rights movement. It was the most visible example of a project that has taken Governor George Pataki three full terms to accomplish and is not yet complete: establishing a solidly conservative appellate judiciary in a state that had a well-deserved reputation for a liberal one.

The 4-2 decisionof the New York State Court of Appeals denying that same-sex couples have a constitutional right to marry was more than just a blow to the gay rights movement. It was the most visible example of a project that has taken Governor George Pataki three full terms to accomplish and is not yet complete: establishing a solidly conservative appellate judiciary in a state that had a well-deserved reputation for a liberal one.

Although the issue of gay marriage may not be the best issue to assess the court's direction, the decision on same sex marriage "does not auger well for the future of civil liberties in this court, " said Art Eisenberg, legal director of the New York Civil Liberties Union.

“Up until recently, this was a centrist court that could go back and forth,” he said. But now, he said, “we are increasingly disappointed by the capacity of the state courts to protect individual rights, so we have chosen federal courts more frequently than state courts to bring our cases.”

The Appeals Court

In their decision in the marriage cases, the high court set out a limited definition of civil rights. Rejecting comparisons between laws barring marriage between African-Americans and whites and same sex marriage, the majority decision said, "Racism has been recognized for centuries - at first by a few people, and later by many more - as a revolting moral evil," while "the idea that same-sex marriage is even possible is a relatively new one." The plaintiffs, said Judge Robert S. Smith, ""have not persuaded us that this long-accepted restriction is a wholly irrational one, based solely on ignorance and prejudice against homosexuals."

Professor Arthur Leonard of New York law school, a leading scholar on gay legal issues, wrote in the Gay City News that to Smith the word “rational,” when used to evaluate legislative action, includes acting out of habit or custom, even in the face of contrary evidence. Smith apparently believes it is rational to preserve existing social arrangements even when they have the effect of discriminating against a segment of society.”

What’s more, Smith failed to note that, just two years before the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed anti-miscegenation laws in 1967 in the Loving v. Virginia decision, the Gallup poll found that 72 percent of Southern whites and 42 percent of Northern whites opposed inter-racial marriage.

Smith is a Pataki appointee, as are two of the three other judges who ruled against same-sex marriage. Both judges who dissented were named to the bench by liberal Democrat Mario Cuomo.

Court of Appeals judges in New York are appointed to 14-year terms, which means that, until recently, Cuomo appointees dominated the seven-member bench on the state's highest court. Three of those Cuomo picks still remain: Chief Judge Judith Kaye and Judge Carmen Beauchamp Ciparick, the two judges who dissented in the marriage case, and Judge George Bundy Smith, who joined the majority.

Bundy Smith--not to be confused with Pataki appointee Judge Robert S. Smith, who wrote the plurality opinion--has a term that ends in September. He is angling for a reappointment by Pataki, even though he would only be able to serve one more year before reaching the mandatory retirement age of 70. Most observers believe that Pataki, now contemplating a run for the Republican nomination for president in primaries dominated by conservative voters, is unlikely to reappoint Bundy Smith, the court's only African American, who had a relatively liberal record. Naming Bundy Smith to the bench again would deprive Pataki of the chance to nominate a more conservative judge for a full 14-year term.

Pataki's successor will have the opportunity to replace Kaye, whose term expires in March 2007, and Ciparick, whose ends in January 2008. The court's current "swing vote," Albert Rosenblatt, a Pataki appointee who recusedhimself in this marriage case because he has a lesbian daughter who has written briefs in favor of the cause, will have to retire when he turns 70 next year.

If the leading gubernatorial candidate, Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, a Democrat, prevails in November, he can replace these three with progressives. But Pataki's mark on the court will still last for seven more years.

Four Pataki judges would remain on the bench: Bundy Smith's likely replacement; Robert Smith, who can serve until the end of the year he he hits 70, 2014; Judge Victoria A. Graffeo, who is done in 2014; and Judge Susan P. Read, whose term lasts until 2017. These judges represent a conservative majority on the court. A new governor would not be able to change that until the end of his or her second term.

The conservative ascendancy in Appellate Division, the state's lower level appeals court, is even more evident, with two of its four departments ruling 5-0 and 4-1 to deny gay couples the right to marry. Associate appellate justices are selected by the governor from among the member of the Supreme Court -- the lower court -- and serve five-year terms. The presiding judge for each department is also appointed by the governor and serves until the end of his or her term. These judges, too, must retire at the end of the year in which they turn 70, but unlike high court judges, they do not have to be confirmed by the state senate.

While U.S. Supreme Court nominations--think Clarence Thomas--have become national circuses, nominations to the New York State Court of Appeals generally sail through the State Senate with virtually no controversy. Up until now, neither liberal nor conservative advocacy groups have made much of an issue of judicial nominations.

But that may change in the wake of high profile cases like the same-sex marriage decision. "Reporters should ask both candidates [for governor] about their plans for court appointments. The stakes are high," wrote Walter Olson of the libertarian Manhattan Institutein the New York Post recently. "For years, New York's high court was among the nation's most prominent liberal voices on criminal-justice issues, delighting civil libertarians and frustrating police advocates with rulings extending Miranda rights, the exclusionary rule and so forth. That's been changing lately as Pataki appointments have joined the court. Republican nominee [John] Faso, who has promised to make crime an issue this fall, may argue that opponent Spitzer is too beholden to Democratic constituencies to follow up on this trend."

Vincent Bonventre, professor of law at Albany Law School and a recognized expert on New York appellate courts, said the Court of Appeals “took a swing to the right beginning in 1996” when Pataki and former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani condemned it as “the most liberal in the country.” Bonventre said, “One of the worst cases was the 1999 case of the People v. Ralph Tortoriciabout an insane guy who held students hostage at SUNY Albany, and the court said it was OK to prosecute him even though they couldn't find one psychiatrist in the state to say he was sane.” As for the Appellate Division, bonventre said, “The first department in Manhattan used to be one of the most liberal courts in the country; now it is one of the most conservative.”

Vincent Bonventre, professor of law at Albany Law School and a recognized expert on New York appellate courts, said the Court of Appeals “took a swing to the right beginning in 1996” when Pataki and former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani condemned it as “the most liberal in the country.” Bonventre said, “One of the worst cases was the 1999 case of the People v. Ralph Tortoriciabout an insane guy who held students hostage at SUNY Albany, and the court said it was OK to prosecute him even though they couldn't find one psychiatrist in the state to say he was sane.” As for the Appellate Division, bonventre said, “The first department in Manhattan used to be one of the most liberal courts in the country; now it is one of the most conservative.”

The New York courts' turn to the right obviously pleases leaders such as Faso, the Conservative and Republican nominee for governor. Responding to the marriage ruling, Faso said, "The Court of Appeals correctly interpreted state law and put the question of the legality of gay marriage squarely in the hands of the Legislature and governor. Like many New Yorkers, I view marriage as both a civil and religious institution. Same sex marriage runs contrary to the religious traditions of millions of New Yorkers of all faiths. If elected governor, I will work to ensure that marriage remains a relationship between a man and a woman."

Next Stop: The Legislature

The fight for gay marriage in New York State will now move to the legislature. But few supporters of same sex marriage predict a quick or easy victory. "It is going to take a while," said Eisenberg. "This is a do-nothing legislature." Assemblymember Deborah Glick, an out lesbian, echoed this, saying, "It is difficult to imagine the state legislature moving in an appropriate or positive fashion [on legalizing same-sex marriage] anytime soon."

Alan Van Capelle, director of the www.prideagenda.org Empire State Pride Agenda, which organized rallies of thousands of same-sex marriage supporters on the day of the decision, said, "There is no reason why gays and lesbians can't win marriage in New York in two years." But he acknowledged that, so far, only 22 out of 151 Assembly members and nine out of 62 state senators have publicly supported such a measure.

"It's time for the Democrats in the Assembly to use their 66-seat majority to pass a marriage equality bill," said Matt Foreman, director of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. But Democratic Assemblymember Andy Hevesi, a supporter of same-sex marriage, said that if a vote were held tomorrow, "it would be close."

As for the two most powerful members in the legislature, Republican Senate Majority Leader Joe Bruno celebrated the court's decision. Democrat Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver issued a statement refusing to comment on it, while promising to take up the issue with his Democratic conference. That meeting is unlikely to occur until after the new members are seated in January.

Spitzer and Bloomberg

The politics surrounding the gay marriage case often seemed surreal. Two politicians who say they support gay marriage played key roles in the defeating it in the court. The office of Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, who promises to introduce a pro-gay marriage bill next year if elected governor, defended the law barring same sex marriage. Mayor Michael Bloomberg, another ostensible supporter of same-sex marriage, successfully appealed the only lower court ruling mandating licenses for gay couples who want them.

The court majority picked up on several arguments made by Spitzer and Bloomberg. For example, the judges said that only heterosexuals can "spontaneously procreate" and that that constituted a "rational basis" for a law that only allowed male-female couples to marry.

"This is Eliot Spitzer and Mike Bloomberg's legacy to the gay community in New York," said Allen Roskoff, president of the Jim Owles Liberal Democratic Club and a longtime gay activist. "They should be ashamed of themselves for arguing against our fundamental right to marry."

Donna Lieberman, director of the New York Civil Liberties Union, said Bloomberg must now "put his money where his mouth is--literally and figuratively," and get behind the campaign to pass an equal marriage bill in Albany with his considerable personal fortune.

Meanwhile, Conservative Party Chair Michael Long has said he intends to use his power to endorse candidates in elections – thereby giving them a second line on the ballot -- to put pressure on many Republicans and a few Democrats to oppose same-sex marriage. And so, with both sides seeking to mobilize supporters and use their power and influence, it seems clear Albany faces a protracted, hard-fought showdown over same sex marriage.

Andy Humm, a former member of the City Commission on Human Rights, has been in charge of the civil rights topic page since its inception in 2001. He is co-host of the weekly "Gay USA" on Manhattan Neighborhood Network (34 on Time-Warner; 107 on RCN) on Thursdays at 11 PM. Â

The Gay Marriage Ruling

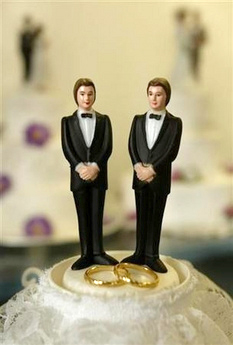

There is no constitutional right to marriage unless your partner’s sex is the opposite of yours, announced the New York State Court of Appeals. The 4-2 split could be summarized as, “It’s all for the children,” versus, “There are enough marriage licenses for everybody.”

There is no constitutional right to marriage unless your partner’s sex is the opposite of yours, announced the New York State Court of Appeals. The 4-2 split could be summarized as, “It’s all for the children,” versus, “There are enough marriage licenses for everybody.”

Same-sex marriage will continue to be barred in this state unless the Legislature changes the law.

The New York City case, Hernandez v. Robles, is one of four combined cases from around the state. After being denied marriage licenses, 44 same-sex couples brought lawsuits seeking to invalidate the Domestic Relations Law and the issuance of marriage licenses to heterosexual couples only. The plaintiffs, who range in age from 30 to 68, and include a doctor, police offer, teacher, nurse and a member of the State Assembly from the Upper West Side, alleged violations of the state Constitution.

In rejecting that argument, the main opinion by Judge Robert S. Smith is based on the theory that the existing laws reflect a rational legislative and state interest.

The opinion deferred completely to the Legislature, though the court clearly has the power to strike down existing laws. Judge Smith wrote, “The right to marry is unquestionably a fundamental right. The right to marry someone of the same sex, however, is not â€deeply rooted.” Therefore, by limiting marriage, the legislature “has not restricted the exercise of a fundamental right.” In her sharply contrasting dissent, Chief Judge Judith S. Kaye said that marriage could not be fundamental for heterosexuals only.

The four judges who voted to uphold existing law (one of the seven judges recused himself) quickly dismissed the argument that the Domestic Relations Law does not specifically say, “man and woman,” finding the heterosexual nature of the statute in references to “bride” and “groom” and “wife and husband.” They determined that, since the law treats women and men alike -- they are permitted to marry people of the opposite sex, but not people of their own sex -- there is no discrimination. It is just heterosexuals and homosexuals who are treated differently.

While the court agreed with plaintiffs and their supporters that there are advantages to marriage in many areas, such as taxes, wills, and insurance, the judges concluded that the denial of such benefits to same-sex couples is not irrational or unconstitutional. In fact, the court found that the legislature has a right to offer “an inducement - in the form of marriage and its benefits … to opposite-sex couples who make a solemn, long-term commitment.”

The opinion spelled out that “heterosexual intercourse has a natural tendency to lead to the birth of children, while homosexual intercourse does not. And, despite the advances of science, it remains true that the vast majority of children are born as a result of a sexual relationship between a man and a woman.” Furthermore, said Judge Smith, “The Legislature could also find that [gay and lesbian] relationships are all too often casual or temporary.... The Legislature could rationally believe that it is better, other things being equal, for children to grow up with both a mother and a father.” This the judge called “common sense.”

The dissenters, though, argued, “marriage is about much more than producing children.”

Both the main and dissenting opinions refer to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1967 decision that laws banning interracial marriage were unconstitutional. According to the Smith opinion, barring gays from certain rights is different. Racism, the decision said, “has been recognized ... as a revolting moral evil” with a “long and shameful” history.

In contrast, the court held that the plaintiffs in the case had not convinced the court that the restriction against gay marriage “is a wholly irrational one, based solely on ignorance and prejudice against homosexuals.” Using language that incensed the gay community, the opinion, while conceding “there has been serious injustice in the treatment of homosexuals,” says, “its history is of a different kind, lacking in centuries of struggle.” One black gay man who attended a Greenwich Village protest following the release of the opinion, said, “It feels the same to me.”

In the dissent, Judge Kaye joined by Judge Carmen Ciparick, wrote that because marriage has previously been limited to heterosexuals does not mean that such a restriction is not discriminatory. In fact, the dissent said, “Limiting marriage to opposite-sex couples undeniably restricts gays and lesbians from marrying their chosen same-sex partners … and thus constitutes discrimination based on sexual orientation.” The dissent continues, “A history or tradition of discrimination does not make the discrimination constitutional . . . it is circular reasoning . . . to maintain that marriage must remain a heterosexual institution because that is what it historically has been.”

Plaintiffs are denied the rights and responsibilities of civil marriage “because of whom they love,” concluded the Chief Judge. She called the decision “a misstep,” and taking a longer view, predicted change in the future. “This state has a proud tradition of affording equal rights to all New Yorkers,” she wrote. “Sadly the court retreats today from that proud tradition.”

Â