How Different Is New York City From The United States?

The population and demographics of New York City are vastly different from most of the United States. Immigrants from the heartland know that this is so, but many long time city residents forget that New York City is not the United States. The recent annual meeting of the demographers (the Population Association of America) in Minneapolis drove this point home.

IMMIGRATION AND RENEWAL

Compared to the rest of the United States, New York City is a city of immigrants and their children. The United States overall is 11 percent foreign born; New York City is 36 percent foreign born. While 82 percent of those that live in the United States speak only English at home, in New York City only 52 percent do so. New York City draws its immigrants from many different countries, while much of United States immigration is from Mexico. As happened at the turn of the century, immigration renewed New York City, but it is doing so by making the city a place vastly different from the rest of the United States.

At the demographers convention by contrast one of the largest trends seen now affecting virtually every European country and parts of the United States are declining birth rates (especially among the "white" population), increasing the proportion of old people compared to the younger population of workers. Women are not having enough babies to replace the population. A United Nations report indicates that to stem this massive trend the European Union would need 135 million immigrants by 2025.

UNMARRIED MANHATTAN

Though fewer and fewer Americans in general are getting married, New York City is less married than the rest of America, which is probably not a surprise to viewers of Sex and the City. For the United States as a whole, about half of all adult men and women are living with their spouses; for New York City, it is about two-fifths, and in Manhattan alone the figure is not even one-third, which makes it the least paired-up major county in America. In their book, The Case for Marriage, Linda Waite and Maggie Gallagher show that married people generally live longer and better by many measures than single people. Of course one does not know if those who are more likely to be healthy and wealthy get married or if marriage brings one health and wealth.

TRENDS AFFECTING NYC, BUT NOT U.S.A.

A series of other trends also affect New York City much more than other parts of the United States, including concentration of poverty, income inequality and its spatial concentration, the special needs of the immigrant populations, health disparities.

Though demographers at the Population Association of America conference came from across the country and around the world, many of the great demographic training centers are in the Midwest and the West. None are in New York, but the city is home to some of the premier demographic institutions including the Alan Guttmacher Institute, and the Population Council. Sometimes the sort of social science conducted by demographers has been derisively called "dustbowl empiricism" in recognition of its midwestern flavor. One cannot help but be struck by how mid-American most US demographers appear. So maybe it is not a surprise that the demographic trends shaping New York are not central to the concerns of most US demographers.

UPDATE: Racial Classification, the Census, and DNA

The great debate about how to collect data on race, Hispanic status and ethnicity and ancestry continued unabated at the Population Association of America conference. At one session a well-known sociologist and demographer made the stunning suggestion that perhaps a good way to classify the racial background of people in the United States would be to use DNA testing. According to this researcher, one can discover the proportion of various racial origins for a specific person by using DNA testing. He cited various websitesthat offer this service. The results of this test purports to provide racial proportions of one's ancestry based upon various regions of the world - which can be directly mapped to races. In a way, this is the high tech version of the 1890 Census interviewer instruction that asked about the racial proportion of the respondent's blood. Panelists and members of the audience questioned the scientific basis of the procedure, while treating the suggestion as absurd.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981. Since 1993 he has done demographic analyses and consulted for the New York Times. He has provided expert testimony in districting and redistricting, housing discrimination, and numerous other civil rights cases in the metropolitan area and elsewhere. The opinions expressed in Topics are his alone.

The Poor In New York City

There are more than a million and a half people in New York City who are living “below the poverty line,” according to official statistics. The poverty line for a family of four was about $18,000 in the year 2000. In a city where many New Yorkers with five times that salary feel that they are just scraping by, some argue that the poverty line should be much higher. But by any measure, poverty in New York City has increased. Almost 300,000 more people in New York City’s population lived below the poverty line in 2000 than in 1990, according to data from the census. In 1990, some 1.38 million New Yorkers -- or 19.3 percent of the population -- were living below the poverty line. By 2000, the number had increased to 1.67 million or, 21.2 percent.

DEFINING POVERTY

Poverty in the United States is defined based upon a formula created in 1963 by Mollie Orshansky. She figured out what income would be needed to purchase the minimum level of food needed for a family. Food was the only area where a clear minimum standard existed. She then multiplied that amount by approximately three, based upon a survey that showed that low-income families spent about one-third of their money on food. Though it has been slightly revised since then, the only real changes have been adjustments for inflation. The thresholds are the same throughout the United States, so those deemed to be “officially” poor in Peoria have the same income as the poor in New York City without regard to different living costs.

A series of other approaches to poverty lines have been proposed,each of these measures giving slightly different results, but no consensus has been reached on what should be the standard gauge.

WHO IS MORE LIKELY TO BE POOR?

Families headed by women with children under 18 are more than twice as likely to be poor (44 percent) as are all families (18.5 percent). Support for elderly through social security has massively reduced the poverty of the older Americans, while poverty among children has increased over the last 30 years: 17.8 percent of New Yorkers over the age of 65 live in poverty, but almost one-third of all children do so.

Many people who are poor at one time do not stay in poverty very long. Indeed, for most people poverty, like unemployment, is episodic. For instance, a student graduates from college and does not immediately find a job. Before finding one he or she might live in poverty. One person loses a job and needs time to find another. During that period that person may have little or no income and might be living in poverty. In such cases, however, official poverty is likely to be short lived. Studies have shown that household dissolution (caused by divorce, death, abandonment, etc.) is the number one cause of poverty, especially for women and children. Job loss is the second major cause of poverty.

When people talk about poverty as a problem usually they focus on the “persistent poor,” those who were born poor and remain poor. Indeed, social scientists (such as several at the Urban Institute) have identified a series of characteristics in the areas where the "persistent poor" are likely to live. These factors include:

- high rates of welfare dependency

- high school dropouts

- female-headed households

- and male joblessness.

Such factors contribute to high levels of urban crime, drug sales, and other urban ills, including graffiti, litter and a lack of neighborhood social control. Abandoned cars, check cashing establishments, advertisements for 40-ounce malt liquor adorn such neighborhoods. Often there are public housing project and high concentrations of minority members.

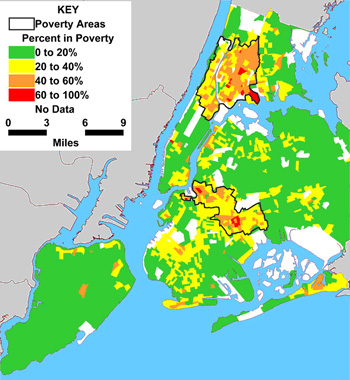

WHERE ARE THE POOR?

Since many poor are not poor for very long, the levels of segregation among poor residents are not that great. Nonetheless, New York City has two areas of concentrated poverty, as shown in the accompanying map. The first is the broad expanse of Northern Manhattan, including Harlem up into the Bronx. This area contains many African Americans and Latinos (especially Dominicans and Puerto Ricans). The other area is centered on Flatbush and Bedford Stuyvesant, also an area with many African Americans and Latinos. (It is important to point out that many Latinos are not impoverished, and there are many areas in New York City with affluent African Americans, including Southeast Queens and Northeast Bronx). The major “poverty areas” contain neighborhoods that traditionally are seen as containing “ghetto poverty,” where the persistent poor are more likely to make their home.

Areas in the South Bronx and areas in and around Bedford Stuyvesant have contained large concentrations of poverty for decades. Nothing that happened in the 1990s changed that. In fact, the poverty population in New York City grew. The 1990s boom did not trickle down enough to pull such New Yorkers out of poverty. The current economic downturn will only serve to exacerbate the problems of the poor and produce more poor people.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981. Since 1993 he has done demographic analyses and consulted for the New York Times. He has provided expert testimony in districting and redistricting, housing discrimination, and numerous other civil rights cases in the metropolitan area and elsewhere. The opinions expressed in Topics are his alone.

Eight Million New Yorkers? Don't Count On It

New York City officially had a population of eight million in 2000, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. But is this an accurate number? Can we know what the actual number was? The answer is: probably not. To complete a truly accurate census two things must happen: First, one must be able to find all the places in New York City where people live. Second, one must count all the people living in each place (and count them only once), whatever the place is (a single-family home, or a dormitory, a prison, a mental hospital, an old age home, or a convent). Census methods do not readily capture New York City's incredible diversity. Assumptions and procedures that easily count Ozzie and Harriet Nelson and their two children (or even Ozzy and Sharon Osbourne and their two children) living in a single family house in the suburbs, do not work well in much of New York City. With its large number of immigrants, households of roommates and unmarried partners, illegally converted apartments and lofts, and homeless and transient population, New York poses unique challenges for enumeration.

2000 COUNT MORE ACCURATE THAN 1990

To improve the 2000 census, the U.S. Census Bureau asked for help from local authorities. Using a variety of city lists and other methods, the NYC Department of City Planning found households that the census had overlooked. Many were concentrated in areas of high immigration, including Northwest Queens, as well as the Bronx and Brooklyn. According to Joe Salvo, director of the Department of City Planning's population division, the Census Bureau sent forms to at least 160,000 of these households. Since the average household in New York City holds 2.6 persons, that means there were 420,000 persons who otherwise would not have been counted. Such households were probably uncounted in 1990, so a large part of New York City's 680,000 population increase was probably just a result of having a more accurate count.

COUNTING HOUSEHOLDS AND MAKING UP DATA

The census uses a variety of methods to contact households and collect census data. First, they send out a form hoping that it will be mailed back. Nationally, about two-thirds are returned. The fraction is lower in the city and varies greatly by neighborhood. Follow-up methods must be used to count those households that do not return the forms. If a phone number is known, the household is called. For those that do not answer the phone, or for which the phone numbers are unknown, enumerators are sent to the household. When, after repeated attempts, no one is found at home, the enumerator contacts a landlord, a supervisor or even a neighbor to confirm that someone lives in the unit. At that point, the census substitutes for those data. Since they do not know how many people live there, they fill in the household responses by using information from a nearby unit. This is known as the "hot deck" procedure, so named because in the distant past, the data was actually processed using computer cards, and the information was drawn from a "hot deck" of recently processed households. In other words, the census makes up data for households that they cannot reach.

To give one small example of the special difficulties in using current methods to get an accurate count in New York City: A trained Census Bureau enumerator, unable to reach individual households, may look at a building that has been divided into a multi-family dwelling and count the doorbells. In one actual example that was explained to me, one house had three doorbells in one location and what appeared to be two additional doorbells in another location. It would seem obvious that a homeowner or landlord may have created additional apartments. But is the presence of five doorbells proof that there are five households? I posed this question to my students who, for the most part, live in Queens. One woman from Elmhurst lived in a single-family home that had previously been divided into three units. Her house, she said, had four doorbells: an older set of three that no longer worked and one working that she had installed. At the same time, my student also had three mailboxes. Since the basic address list that the U.S. Census Bureau uses is from the U.S. Postal Service, she received three census forms instead of just one.

The census expects one person to fill out the form for each household. Even where data are supplied by one of the occupants of a unit, difficulties may ensue. In certain cases, the degree of cooperation or knowledge about the other residents may leave something to be desired. For understandable reasons, sets of roommates, boarders, illegal immigrants, and live-in household help (who may or may not be documented) may be purposely omitted. When the long form, which is received by about one-sixth of households and includes detailed data on economic standing, occupation, education, housing cost, migration, birth place, and the like, is involved, missing data are even more likely. If characteristics of some individuals are left blank, the census bureau imputes (makes up) those data. In short, the results from every census include made-up data for entire households and for particular characteristics for particular individuals. According to preliminary results such made-up data for NYC increased greatly since 1990.

ANOTHER APPROACH THAT MAY BE MORE ACCURATE

Since 1980, demographers and survey research experts, backed by a report by the National Academy of Sciences, have advocated "statistical sampling" to get at the hard to enumerate households. By this approach, the census bureau would use completed interviews or questionnaires with residents in most households. But for those that proved difficult to reach, they would attempt to interview only a random sample, perhaps one in ten. Results from that sample would be used to estimate the number and characteristics of all of the unreached. These sample interviews would be done by well-trained enumerators, who would use their resources to "get answers" from the hard to reach households.

Though backed by most scientific opinion, the use of statistical sampling in the census is highly controversial. The GOP, perhaps fearing that it would increase the numbers and thus the power of Democratic urban areas, has consistently blocked its use. Scientific procedures to get a more accurate count have repeatedly been rejected by Congress and two Bush administrations. As late as this month, the director of the Census Bureau rejected any sort of adjustment or correction for ongoing programs of population estimates. Instead for Census 2000, Congress allowed the bureau to pour billions of dollars into coverage improvement to help reach more of the hard to count, but still required that every household be enumerated. As we begin to prepare for Census 2010 most demographers think it would make sense to follow the recommendation of a panel of the National Academy of Sciences and use statistical sampling.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981. Since 1993 he has done demographic analyses and consulted for the New York Times. He has provided expert testimony in districting and redistricting, housing discrimination, and numerous other civil rights cases in the metropolitan area and elsewhere. The opinions expressed in Topics are his alone.