Where The Funds Stand

Giving to the government may seem a little ridiculous to some New Yorkers. But just in case you were thinking about it, we have taken a look at the charity watchdog ratings of a few government "charities" to see how your dollar would be spent. These ratings do not take into account the mission of the charity, and only examine their financial standings.

|

For those that are looking to donate this holiday season here are some watchdogs to check out first. Charity Navigator: rates charities on organizational efficiency, organizational capacity and how an organization grows. Better Business Bureau of Metropolitan New York: rates charities based on 20 standards, from governance and oversight to finances. New York State Attorney General's Office: Oversight of all charities is conducted by the attorney general's office. |

The Mayor's Fund to Advance New York City: Out of the 562 large charities scored by independent charity watchdog, Charity Navigator, the mayor's fund ranks as the best bet for your dollar. It received the highest ranking from the group, which is four stars, but it does not meet the Better Business Bureau’s twenty standards. According to the bureau’s evaluation, the fund does not clearly identify officers on its website nor does its budget clearly identify how much is spent on fundraising and programs. According to Charity Navigator, the fund spends 98.6 percent of its funding on programming, 0 .9 percent on administrative expenses and 0.3 percent on fundraising.

Fund for Public Schools: It met all of the Better Business Bureau's standards and was awarded a four star rating from Charity Navigator. The fund spends 96.5 percent on programs, 2.7 percent on administration and 0.7 percent on fundraising.

Aging in New York Fund: According to the Better Business Bureau, the Aging in New York Fund received nearly $2.8 million from July 2004 through June 2005. However, it did not meet all of the bureau's charity standards because its budget did not clearly identify how much it spends on administrative services and fundraising. The fund spends 83.4 percent on programming, 13.9 percent on administration and 2.8 percent on fundraising.

City Parks Foundation: According to Charity Navigator, the City Parks Foundation brought in nearly $9 million in revenue last year, but it received only two out of four stars. Because Charity Navigator measures an organization's growth, the foundation claims the watchdog does not accurately reflect it finances. The foundation said it helps start-up groups raise money and acts as fiscal sponsors. When that group is ready to become independent, the foundation transfers the fund it had raised for it. In the rating process, that makes the foundation appear as if it is losing program, when it is not, according to the foundation.Charity Navigator found the foundation spends nearly 80 percent on programming, 10.9 percent on administration, and 9.3 percent on fundraising.

Â

Managing Billions in City Contracts

In the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2007, the City of New York completed over 50,000 procurements worth a total of $15.7 billion. Through contracts and purchase agreements with 49,674 for-profit and non-profit vendors, the city used this enormous sum to buy goods and services and undertake capital projects. In human services alone, the city in 2007 had contracts worth $3.8 billion with various firms.

In addition, the city contracted for $3.5 billion in construction services, $3.7 billion in so-called standardized services (security, transportation, food services, etc.), $3.4 billion in professional services (legal, accounting, auditing, consulting, etc.) and $1 billion in goods. This information comes from the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services latest report, Agency Procurement Indicators for Fiscal 2007.

The contracting report was previously part of the semi-annual Mayor’s Management Report, but under Mayor Michael Bloomberg it has become a stand-alone document that gets even less attention than the MMR (see the October Finance column). One reason for its obscurity is that, like recent management reports, it is essentially a collection of statistics and program descriptions. Another is that it has even less analysis of management matters than the Mayor’s Management Report. Arguably, only three of the contract report’s 99 pages measure recent performance over time.

Worse, one of the two measures of performance celebrated in the three pages – the timeliness of human services contracting – is contradicted in several instances by statistics published by the city comptroller’s office, the office that, under the City Charter, registers contracts.

The other positive performance indicator – evaluations of service contracts – is cryptic. It notes that only 47 of 4,603 vendors evaluated – 1 percent -- were deemed unsatisfactory. Another 138 vendors (3 percent) were deemed in “need of improvement.” Thus 96 percent of all vendors evaluated performed satisfactorily or better in 2007. That’s all we get, since agency-specific evaluations were dropped from the report after 2005.

What the Report Says

The bulk of the contract report describes recent and forthcoming projects, including preliminary efforts to expand opportunities for businesses owned by minority-group members and women and for environmentally friendly purchasing.

It also throws a spotlight on new major areas of city investment:

--Technology, where the city plans to put out over $1 billion in contracts to develop a citywide mobile wireless network and citywide local and long-distance voice and data telecommunications services for all city agencies.

-- Solid waste management, where the report cites over $1 billion of recent and future contracts for truck purchases, disposal and new facilities.

-- The mayor’s ambitious PlaNYC2030 for a more environmentally sustainable city.

All of these programs underscore the fact that big contracts dominate the procurement system: The biggest 25 contracts represent about half of the $15.7 billion of procurements. The top seven contracts in 2007, for instance, each ranged from $500 million to $1.2 billion.

What the Report Does Not Say

These new programs raise an old question: How do we measure results? As presented in the report, there are no publicly announced base lines for big new, or old, investment programs, no specific performance goals, no performance measures for these huge dollar commitments. Yet the need for such performance indicators is reflected in the trouble the city has had fulfilling technological goals in a social services information system and improving police/fire communications, as cited in the 9/11 Commission Report.

The one section of the report that attempts to measure recent performance looks at the timeliness of contract registration. Without prompt registration, providers cannot get paid, and delays can be a sore point, particularly for non-profit organizations. But the performance methodology is narrow. A table in the appendix looks only at one year, and the text offers only few comparisons to the previous year. This ignores the five-year data in the Mayor’s Management Report.

In addition, the timeliness information in the contracts report is inconsistent with the results of similar measures used by the comptroller. The contracts report analyses retroactive contracts – those where the start date for services comes before the contract is registered -- at six human service agencies: aging, youth and community development, children’s services, homeless services, health and social services. According to the contracts report, the Department for the Aging for the second straight year had no contracts that were more than 30 days late. But the comptroller’s report says that 99 contracts – or 32 percent of the agency’s total -- were registered more than 90 days late in fiscal 2007.

Similarly, the contracts report says only 34 percent of contracts in the Department of Youth and Community Development were retroactive in 2007. But the comptroller says 76 percent of all youth department contracts were retroactive in 2007, and 87 percent of those were late for more than 90 days.

At children’s services, the results are much more positive. The comptroller says only 7 percent of children’s services contracts were retroactive, down from 32 percent in 2005. In this case, the contracts office records a higher percentage (16 percent) of retroactive contracts in 2007.

In another comparison more favorable to the city, the comptroller’s report notes a lower percentage (27 percent of late contracts in homeless services in 2007 than does the contracts report (53 percent) does

The inconsistencies between the findings of MOCS and comptroller reports are perhaps most troublesome in their recordings of the average number of days retroactive contracts were late in 2007: MOC says the range was 17 days late at the aging department to 107 days late in the health department) the comptroller says the range was 140 days (homeless services) to 230 days (youth).

Retroactive contracts in all six agencies are late by an average of 52 days, according to the contracts report, 196 days, according to the comptroller. In other words, with some exceptions, the comptroller paints a much bleaker picture of agency management than the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services.

A Case in Dispute

With so little information available about how city agencies deal with contractors, it’s useful to look at the city comptroller’s most recent audit of an agency’s management practices. The comptroller’s audit of the department’s oversight of the Ferry Point golf course project in the Bronx finds many deficiencies in its management system. Although it is only one, rather small vendor deal (less than $10 million of city funds originally), the problems raise questions about oversight and management that are ignored in the Office of Contract Services report.

The $22 million privately funded project, on the site of a former landfill, was conceived during the Giuliani administration in the late 1990s, but most of the project has evolved during the Bloomberg administration. The city entered into an agreement with a firm that would build the golf course.

The city agreed to pick up the costs of correcting the environmental problems at the site, up to about $8 million. The audit argues that the city mismanaged oversight of the project, overpaid for reimbursements to the concessionaire (Ferry Point Partners) by nearly $6 million, lost more than $3 million in anticipated revenue and permitted a construction company to get fees from acquiring fill for the golf course that could have produced as much as $10 million for the city.

The city recently canceled the agreement with Ferry Point Partners and the project, originally slated for completion in January 2003, remains unfinished.

The parks department has rejected most of the criticism in the audit. “The audit reflects numerous errors in both fact and law and a fundamental misunderstanding of a highly complex project and its associated regulatory permitting process,” commissioner Adrian Benepe said. The commissioner blamed the state department of environmental conservation for much of the delay.

In an unusually testy exchange, the comptroller’s auditors repeated many of their original charges. “The [parks] department’s response attempted to obfuscate the serious issues raised in the report,” the office said. ”Clearly, the department has failed to understand the salient conclusion of this audit report – that the department has not properly overseen and managed the administration of the Ferry Point concession.”

The most serious charge in the audit is that there was no effective management system. The report says, specifically, there was no scope for the remedial work to be done on the contaminated site, no breakdown of the costs of remediation, no written procedures for oversight and no full-time project manager for the oversight work. The administration rejects all these charges.

The volatile exchange between the comptroller’s audit office and the parks commissioner underscores how little the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services report includes that would help measure performance. Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

Wall Street's Binge, Workers' Hangover

The turmoil and uncertainty on Wall Street continues, punctuated by Merrill Lynch’s recognition last month that it had lost $8 billion in sub-prime backed mortgage securities. The profitability of many of New York’s financial giants has eroded and layoffs have multiplied, worrying city and state budget makers.

The latest losses, following three years of big gains, indicate the pitfalls of Wall Street’s all too frequent speculative binges. Wall Street’s tendency to create investment fads that enrich the few at the expense of the many, whether through dot.coms, Enrons, risky mortgages or whatever might come next, is not a smart way to run an economy. Beyond that, it all too often distracts attention from the financial realities facing people who live and work in the broader economy beyond Wall Street.

So, how are those people doing and how are they likely to fare if Wall Street’s woes continue?

Lately, wages and incomes have improved a little. Given that the economy has been in recovery since mid-2003 from 9/11 and the recession earlier in the decade, some gains should be expected. What’s surprising is that they took a while to materialize.

Against this backdrop, however, there are some troubling long-term trends in the New York economy. These trends have a lot to do with the economic well-being of average people and the neighborhood economy as opposed to the Wall Street economy that receives most of the media attention.

INCREASES IN INCOME

First, let’s take stock of the good economic news.

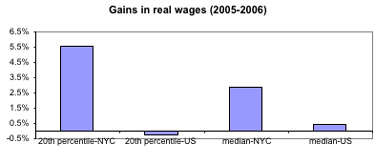

Hourly wages for most New York City workers, after adjusting for inflation, rose in 2006 and now are roughly back to 2002 levels. The New York worker in the exact middle of the pay scale made $15.38 an hour in 2006, 2.9 percent more than in 2005.The worker at the 20th percentile of the wage spectrum – a level representative of a low-wage worker – earned $9.27 an hour in 2006, 5.6 percent more than in 2005.

And as the graph below shows, wages for typical workers last year fared better in New York City than in the country in general.

NYC VS. U.S. 2005-2006, MEDIAN AND 20TH PERCENTILE HOURLY WAGE

Undoubtedly, earnings for low-wage workers received a boost from the increases in New York State’s minimum wage in 2005 and 2006 while the federal minimum wage of $5.15 remain unchanged until it was finally increased this July. New York’s minimum wage is now $7.15 an hour (a third and final increase took effect in January). The first of three annual 70-cent increases in the federal minimum wage lifted it to $5.85 in July.

Median family income has risen in New York City since 2003, climbing to $51,830 in 2006. Taking inflation into account, family incomes increased 3.9 percent between 2004 and 2006. This improvement resulted from increased wages and a slight increase in the number of people working. (It may also be that some of the apparent family income improvement results from a number of moderate income people –- those with incomes from $40,000 to $60,000 -- leaving the city, possibly due to rising housing costs and being replaced by more affluent household. See this report from the city comptroller’s office.)

Still, the city’s median family income is slightly more than 10 percent less than the U.S. median family income of $58,526.

SIGNS OF TROUBLE

The recent improvements in wages and family incomes are certainly welcome, but they could be short-lived given the turmoil on Wall Street and the likelihood that the national sub-prime lending crisis and housing market troubles will decisively slow overall economic growth. There is a growing realization that a good part of the national growth of recent years was fueled by the reckless expansion of sub-prime lending and other questionable Wall Street practices. Growth was fueled by excessive borrowing because there was not a broad-based growth in incomes.

There is more to the lopsided character of economic growth than irresponsible lending and the collapse of the housing bubble. The Fiscal Policy Institute’s recent The State of Working New York 2007 report highlighted other “troubling trends” that put recent economic news in perspective. These “troubling trends” characterize the state’s as well as New York City’s economy.

The “Productivity-Wage Gap”

Overall consumption spending has out-paced any growth in income and wages. Workers have not been sharing in the fruits of their labor. The “productivity” of New York workers – the value of what they produce -- has risen by over 11 percent since 2000 while inflation-adjusted average wages grew by only 1.1 percent. The emergence of this “wage-productivity gap” since 2000 is reflected in the fact that nationally, corporate profits have grown four times faster than total wages over the last six years.

Less Job Security, Fewer Benefits

An increasing number of businesses are hiring workers as “independent contractors” in place of employees. This results in a deterioration of working conditions and puts strains on social insurance systems. Employees get a range of benefits long taken for granted and essential to middle-class economic security: overtime pay, sick leave, co-payment of Social Security and coverage by workers compensation and unemployment insurance. As an “independent contractor,” a worker gets none of these. Nearly 10 percent of all private workers in New York are “misclassified” as independent contractors. The economic well-being of such workers undoubtedly falters compared to the status of a regular payroll employee.

This “misclassification” trend is part of the broader pattern of unregulated work and employer noncompliance with labor laws. Governor Eliot Spitzer recently issued an Executive Order, establishing an inter-agency task force to crack down on the illegal use of independent contractors.

Poverty-level Jobs

Despite recent wage and income gains, the number of working families who are poor or near poor is much higher now than it was in 1990. Today, poor people are more likely to have a job than was the case 15 years ago. Since so many jobs pay very low wages, having a job is no assurance of a decent standard of living. The number of people in working families in New York City who are poor, as defined by the federal poverty standard, has risen by two-thirds (222,000) from 1990 to 2005. Some 560,000 New Yorkers live in poor families, including over 250,000 children. Nearly half (47 percent) of children in working families in New York City live in families with incomes less than twice the poverty level. (The federal poverty level for a family of four is now about $20,000 a year).

A Widening Income Gap

Census data for 2006 confirm that New York State has the widest income gap between the rich and the poor (and the widest gap between the rich and the idle) of all 50 states. New York City’s income gap between the rich and the poor is considerably greater than for the state as a whole. In 2004, the richest 5 percent of people in the state accounted for 38 percent of all income while in the city, the top 5 percent garnered 47 of all income. Recent projections by the state Division of the Budget indicate the share of income flowing to the richest five percent jumped markedly between 2004 and 2007, a statewide trend that would also be evident in New York City.

All indications are that New York City’s economic recovery and expansion that began in mid-2003 is tapering off. The wage and income gains for most New Yorkers that finally materialized over the past year or two could be short-lived.

To confront this should involve more than crossing our fingers and waiting for the next Wall Street bubble to make things better. As with the increase in the minimum wage and the pending crackdown on the “misclassification” of workers, policy makers need to hone in on changes that will make a difference for average people striving to make ends meet in a city with a rising cost of living and in an economy that is all-too-prone to Wall Street-driven boom and bust. Otherwise, the “troubling” longer-term trends will completely swamp the short-lived gains that show up only at the top of the boom-bust cycle.

James Parrott is deputy director and chief economist of the Fiscal Policy Institute (www.fiscalpolicy.org). He has been studying and writing about the New York economy since he landed in New York City a quarter century ago.Â