Mayor's Management Report for 2005: Thinner, Less Useful

Michael Bloomberg released his mayor’s management report for fiscal year 2005 on September 12, one day before the Democratic primary election, a preemptive strike against his political opponents. Fair enough: The report is required by the city charter in order to give voters a useful measure of mayoral accountability.

In this latest report, the mayor says that his administration has achieved “high levels of service delivery [and] in some cases, historic progress.”

But much like last year’s report, this one gives voters little help. It includes too many insignificant indicators, lacks any overview or sense of priorities, and says little or nothing about such major (and problematic) policies as the reorganization of city schools, big changes in homeless services, the costs of school construction, and high levels of overtime among the city’s uniformed services.

And a number of recent surveys and independent management studies challenge the mayor’s rosy assessment, identifying some real problems and providing an alternative view of mayoral accountability.

SMALLER, BUT BETTER?

The printed version of the 2005 Mayor’s Management Report is much smaller than the ones put out during the administration of former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani (276 pages in 2005, compared to 1,162 pages in 2001). Many observers admire this change, including most participants at an expert panel sponsored by the mayor’s charter revision commission on April 4. But one dissenter on that panel, deputy city comptroller Greg Brooks, pointed out that smaller is not necessarily better.

Brooks noted a net reduction of 1,087 indicators (from 2,606 in 2002 to 1,519 in 2004), a 42 percent cut. He also noted that 16 percent of the 1,519 remaining indicators are related to 311, creating what he characterized as a “soft indicator of the quality of city services [that] could in fact skew results.”

The good news is that the mayor’s management report does have a number of useful statistics, if not many performance indicators. It provides glimpses of current city demographics and some social conditions. The basic problem is that the report does not connect the dots between those facts and city policy.

Some of the more glaring examples include:

- Graduation Rates

- Between 2001 and 2004, the percentage of students graduating from high school within four years increased, from 51.0 to 54.3 percent.

- But in the same period, the percentage of students graduating from high school within seven years declined, from 69.5 percent to 68.0 percent.

Issue to connect the dots: What improves/impedes graduation rates?

- Special Education

- From 2001 to 2005, NYC student enrollment has decreased by nearly 30,000, to 1,075,300.

- But in the same period, the number of special education students has increased by 5.5 percent, from 167,800 to 177,100.

Issue to connect the dots: Is a higher percentage of students in special education good or bad?

- Homeless Families

- Between 2001 and 2005, the average number of homeless families in shelters per day has increased by 55 percent, to 8,623 (including 14,849 children).

- In the same period, in spite of a focus on “prevention,” there’s been a 46 percent increase in families entering the shelter system for the first time (6,618 in 2005).

Issue to connect the dots: What’s the actual impact of prevention work?

- Crime

- Since 2001, major felony crimes have decreased by 21 percent (murders by 15 percent, rapes by 11 percent), from 172,646 to 136,491.

- But the number of uniformed officers has decreased in the past four years by 3,141, or eight percent.

- And in the same period, police overtime has increased by 20 percent, from $338 million to $406 million.

- And over four years civilian complaints against police officers increased by 46 percent, to 6,358 in 2005.

Issue to connect the dots: Are officer levels, overtime, crime statistics, and civilian complaints related?

THE VIEW OUTSIDE CITY HALL

What The Customers/Constituents Say On Education

One performance indicator that would improve the mayor’s management report in many agencies is the constituent/customer survey. In June the city council’s education committee published an education oversight report card, based on a survey of 689 parents and 30 teachers. Using a state-based grading system (1=Not Proficient, 2=Basic, 3=Proficient, 4=Advanced):

- Three of 14 categories – class size, teacher and principal morale, special education, and operations -- got the lowest score of 1.

- High school admissions got a 3, and competition and choice a 4.

- All other categories (including instruction, communication, and parent involvement) received 2’s.

The Quinnipiac University September 22 poll of 1,504 NYC registered voters reported mixed public judgments of school performance: Some 66 percent of voters are dissatisfied with the public schools (an improvement from earlier polls over the past three years that showed dissatisfaction ranging as high as 78 percent). But the mayor got a 52 /33 percent approval/disapproval rating for his public education role, and chancellor Joel Klein a 40/33 percent rating.

Overall, 12 percent of voters were “very satisfied” with the ways things are going in the city, with 51 percent “somewhat satisfied,” 22 percent “somewhat dissatisfied,” and 13 percent “very dissatisfied.”

What The Independent Monitors Say

The city comptroller’s office and the NYC Independent Budget Office, like the the city council, serve as alternative governmental sources of accountability measures, particularly in data and technology areas. For instance, the comptroller’s May 2 audit of "the paperless office system" of the Human Resources Administration showed that a system that has cost $47 million and was (according to the 1996 Mayor’s Management Report) to be completed by April 1998, has yet to be finished.

Furthermore, HRA did not provide complete documentation of the many contracts associated with this project, and gave “the false impression” that the paperless office system “was progressing smoothly.”

The Independent Budget Office’s September fiscal brief, "Follow the Money: Were School Construction Dollars Spent as Planned?” (in pdf format) identified major problems with reporting systems: “Determining how successful the education department was in implementing its $6.9 billion 2000-2004 capital plan was a difficult task, plagued by inconsistent and missing data….The lack of detail linking the spending to individual projects limits the comparison between plan and actual.” (This is just what the mayor’s management reports are supposed to do, but don’t.)

In spite of the data restrictions, the IBO doggedly pursued a projected vs. actual cost study of a small part of the total capital plan -- 14 new elementary and four new high schools. The study found that actual spending was 22.0 percent and 38.1 percent higher per square foot in the elementary and high schools, respectively, than projected in the original plan. (The study suggests those percentages may be understated.)

SPECIAL EXAMPLE: SPECIAL EDUCATION

For decades 110 Livingston Street, the city Board of Education’s central office in Brooklyn, was a notorious symbol of the modern bureaucracy – distant, unresponsive, ineffective. Mayor Bloomberg, newly in charge of public education and sensitive to the symbol, moved central headquarters to the Giuliani-renovated Tweed building, next door to City Hall (although the $100 million cost of its renovations and the building’s association with the city’s most famous crook raised some eyebrows).

But has the mayor simply created a different monster? A new management study of Bloomberg ’s reorganization of special education describes an eerily familiar structure -– “a bureaucratically-driven” agency that has continued bad old policies and created a new set of dubious policies and procedures. Written in a polite and technical academic style, the study lays out an astonishing range of management problems, from complex and confusing infrastructure and ineffective data systems to a central-office reliance on an old “medical model of treatment” that the researchers say contradicts current best practices.

“Comprehensive Management Review and Evaluation of Special Education” was written by a team of seven researchers, headed by Thomas Hehir, a lecturer at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Contracted by the city’s department of education, its purpose was “to critically assess the recent reorganization of…special education evaluation and placement processes and special education oversight in light of the Jose P. litigation.”

The study is independent of both the department and the plaintiffs in that litigation, which has been in place since 1979, when the city was found in violation of the federal Education for All Handicapped Children Act (now the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004).

The report is also the first significant study of the core element of the mayor’s overall reform of education -– a highly centralized operation that has created 10 regions out of 32 community school districts and re-structured special education in those 10 regions.

The study says, in sum, no, the department does not yet have an effective management structure. Of 14 findings, nine are negative. Five positive findings applaud the commitment of the agency’s many teachers and specialists to their work. But six of the nine negative findings show structural and management problems:

- “The complex …infrastructure…leads to confusion with respect to roles and responsibilities and does not provide sufficient support to principals and school staff.”

- “The management of special education…is not sufficiently data-driven.”

- Policies and procedures “are not being communicated to personnel in an effective manner.”

- Pre-referral measures “are implemented inconsistently and are often duplicative.”

- “[A]n effective [due process] system is still not in place.”

- Staff development efforts “are insufficient.”

The other negative findings are more conceptual in nature. The authors question the special education medical model that the mayor and chancellor have inherited but also seem to have adopted. The report argues that the model leads to “treatments” by specialists and therefore unnecessary segregation of services. They suggest shifting to a more comprehensive, integrated, and local set of services.

The 2005 Mayor’s Management Report says nothing about these significant management and policy questions (special education in the 2003-2004 school year represented nearly 25 percent of the education budget, or $3.4 billion). The department press release accompanying the study quotes only its statement that the department is “moving NYC in the right direction.” It ignores the specific litany of structural/ management problems.

The mayor’s recent charter revision commission considered (and ultimately tabled) a mayoral initiative to reduce the number of reports. The thinness of the current mayor’s management report indicates that the problem is not too many reports. The problem is too few that are useful.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

The Fiscal Crisis After 30 Years

It was a dramatic time, Felix Rohatyn recalled: “Almost daily crises … heroes and villains; us against them." In short, he said, it was “the most rewarding experience of my professional life."

Few people would sound so nostalgic about the fiscal crisis of 1975, a time that saw massive layoffs, piles of garbage in the street because of cutbacks in the Sanitation Department, and a dangerous decrease in police patrols. But of all the experiences in his long life, Rohatyn takes the most satisfaction from his role in saving New York City from bankruptcy.

At the time, the federal government accused the city of handling its money like a heroin addict, focusing only on its next fix -- relying on deceptive accounting, borrowing excessively, and refusing to plan. This led banks to stop lending the city money.

|

Ballot Questions Question 1 -- Amending the state budget process. |

Now, 30 years later, says Rohatyn, the city’s good financial management is taken for granted. It has honestly balanced its budget for over 25 years, and has rebuilt trust among the banks that refused to lend it money in the 1970s. The Financial Control Board -- a state-ordered budget watchdog that Rohatyn helped form -- is given much of the credit for this turnaround.

But with the law that created the Financial Control Board set to expire in 2008, Rohatyn and others are concerned that the city may relapse.

This November, New Yorkers will vote on whether to put some of the practices that the Financial Control Board requires into the city charter. Most budget experts agree that these requirements are good ones. But some worry that without an external monitor New York City will slide back into the habits that caused it so much trouble in the past.

To see what happens when no discipline is imposed on budget makers, many point to New York State. Albany now regularly engages in the kinds of behaviors that the Financial Control Board has weaned the city from.

The state’s budget is also the subject of a referendum this November. If passed, it will change the roles of the governor and the legislature during budget negotiations. This proposal will not directly address financial mismanagement, but its advocates hope that by increasing accountability and transparency, the new budget process will force state officials away from their worst budgetary tendencies. Opponents of the measure, though, say that the amendment will only make such problems worse.

THE 1975 FISCAL CRISIS

New Yorkers continue to debate what drove the city to the brink of bankruptcy in 1975.

Some argue that New York City’s liberal officials borrowed money freely to spend on social programs, while powerful municipal unions forced them to agree to obscenely generous contracts. Others say that a variety of outside factors were a driving factor -- the city was increasingly tied into a world economy that was in shock from the 1973 Arab oil embargo; it was victimized by the banks upon which it relied to buy bonds; the federal government left the city in the lurch.

Some argue that New York City’s liberal officials borrowed money freely to spend on social programs, while powerful municipal unions forced them to agree to obscenely generous contracts. Others say that a variety of outside factors were a driving factor -- the city was increasingly tied into a world economy that was in shock from the 1973 Arab oil embargo; it was victimized by the banks upon which it relied to buy bonds; the federal government left the city in the lurch.

Rohatyn saw enough blame to go around (in pdf format):

"The banks had lent too much and checked too little; the unions took more than the city could afford; the city cooked the books, and borrowed; and the state encouraged this whole exercise," he said.

Whether or not they were the root cause of the crisis, New York City’s financial practices were out of control at that time, say experts. The city was relying excessively on debt; by Rohatyn’s account its short-term debt had risen from about zero in 1970 to $6 billion in 1975. The city relied increasingly on budgetary tricks to balance the budget –- reclassifying operating expenses as capital investments; continuously pushing expenditures onto the following year’s budget; or simply not keeping good enough records to know what was really going on.

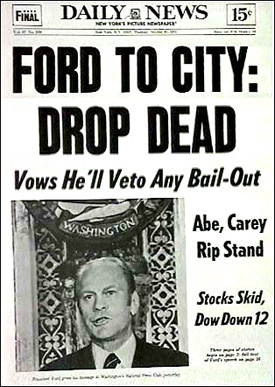

Ken Auletta writes in his book The Streets Were Paved With Gold –- one of numerous books written on the topic -– that the city acted as if it wasn’t bleeding to death when in fact it was hemorrhaging severely. But when first the banks, and then the federal government, declined to bail the city out (the latter prompting one of the most famous tabloid headlines in New York history: FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD), it became apparent that something needed to be done.

The answer, in Auletta’s words, was “fiscal martial law.”

THE FINANCIAL CONTROL BOARD

To get the city's fiscal matters in order and convince investors to resume the purchase of the city's bonds, New York State established the New York City Emergency Financial Control Board. The board was comprised of the mayor, the governor, the city and state comptrollers, and three private industry experts. It held veto power over the city’s budget.

The board required the city to adopt accepted accounting practices, to end the most egregious budgetary sleights of hand, and to work towards the type of fiscal responsibility that would convince banks to trust New York. The city was able to avoid declaring bankruptcy, and in 1982, banks resumed buying short and long term municipal bonds.

The board’s veto power over the city budget -– the so-called control period -- ended in 1986. Since then, the board has served a monitoring role, with the ability to resume its active role if the city’s budget deficit exceeded $100 million at the end of a fiscal year.

So far, the city has successfully avoided such action.

"The city of New York today, I believe, is probably the best governed in terms of finances," said state comptroller Alan Hevesi. "Our reporting systems, our financial transparency, are probably the best in the country. And that's because of this law [that created the Financial Control Board]."

The board has had several lasting effects on the way the city's budget process works:

Making the Governor a Partner: One of the primary reasons for establishing the financial control board was to force the governor and the mayor to be partners in making sure the city is healthy financially. Because the governor sits on the board, he is directly responsible for the city’s performance. The board also provides the state with a permanent structure for keeping abreast of the city’s finances without creating the tension that can arise from state investigations of specific city practices.

Political Cover: Something that became clear during the 1975 fiscal crisis was that good financial and budgetary practices sometimes run counter to good politics. City officials have an incentive to put off difficult decisions. By forcing officials to make these decisions, the board becomes a willing scapegoat.

"Whatever those decisions are -- taxes, service cuts -- they are going to be unpopular to some sector of the city," said Jeffrey Summer, executive director of the board. "And if we take the blame for it, that's fine, so long as the city does it."

A Culture of Accountability: The board’s most widely cited accomplishment has been to give an air of credibility to the city's budget numbers. New York City's accounting, which has been suspect in the past, is now trustworthy. Because the board requires the city to have a four-year financial plan, officials must also address future consequences of their actions. Good financial management, said Rohatyn, has become “part of the city’s DNA.”

There is a general acknowledgement there is a culture of discipline among city officials that has not existed in the past. Still, some remain skeptical about the durability of this shift.

"There has been a vast change in what people think they can get away with," said E.J. McMahon of the Manhattan Institute. "But has the culture really profoundly changed? No."

THE END OF THE BOARD?

The control board is scheduled to exist until 2033. But in 2008 it will lose its $3 million in annual funding and its ability to impose a control period over the city.

Some think that the board should be allowed to expire, arguing that the city has earned its independence through its performance since the 1975 fiscal crisis. They argue that the city and state comptrollers, the Independent Budget Office, the Citizens Budget Commission are monitoring the city closely enough to make sure it doesn’t backslide -- despite the fact that all of these organizations except the Independent Budget Office existed before the fiscal crisis.

"I think that [the board] has handled itself very well, and I think that when it expires it did a good job and left a legacy, but there's no reason for it to be in business," said former mayor Ed Koch.

Not everyone agrees. Because the board has the option to impose a control period, it alone has the power to force the city to act responsibly. Taking this away, some say, is dangerous.

"This is like talking about allowing just a little sip of table wine in the house of a raging alcoholic who once almost killed himself," said McMahon.

McMahon argues for a “permanent, semi-mothballed” board that can step in if the city performs badly. Both the state and city comptrollers also say that the law that created the board should be extended in some form. (The board itself has no stance on whether it should continue to exist.)

BALLOT QUESTION 4: PROPOSED REVISION TO THE CITY CHARTER

Seemingly in preparation for the board’s expiration, Mayor Michael Bloomberg has proposed revisions to the city’s charter that voters will decide on in November (in .pdf format). These revisions would require the city to balance its budget using generally accepted accounting standards, create a four-year financial plan, and limit the use of short-term debt – all things the board currently requires.

This would give the city added independence while guaranteeing continued financial responsibility, argue proponents: “As there always has been the sense that the city should have more autonomy in self-government, this proposal would create the ability for the city to monitor itself regarding financial matters,” wrote the Women’s City Club of New York in a statement.

Frank Mauro of the Fiscal Policy Institute, however, argues that the provisions become ineffective when there is no one outside the administration specifically assigned to make sure that the city upholds its responsibilities.

Still, other fans of the board don’t necessarily object to the city charter revisions. Deputy City Comptroller Marcia van Wagner says that the revisions encourage good behavior and should be supported; they should just not be used as justification for eliminating the board itself.

“There's no harm in [the revisions],” she said. “But I think what people feel is that there needs to be some kind of discipline that is imposed externally."

NEW YORK STATE’S FISCAL MISMANAGEMENT

In contrast to New York City, New York’s state government has not been forced to answer to an outside entity. The results, say budget experts, have clearly been destructive.

“I think the behavior of the city and the state, in terms of how they run their budget process, has diverged tremendously to where the city now adheres to very high standards, and the state is not adhering to the low standards it has,” said Diana Fortuna of the Citizens Budget Commission.

Among the behaviors cited as particularly dangerous are:

Borrowing for Operating Expenses: While the city has limits on short-term debt, Albany borrows to pay its operating expenses. State comptroller Alan Hevesi refers to this as the “cardinal sin” of finance, and others have likened it to taking out a mortgage to pay for groceries.

Unbalanced Budgets: Unlike city officials, state budget makers are not required to balance the budget according to general accounting principles. Albany regularly runs large deficits.

Outstanding Debt: The state doesn’t have the debt limits imposed on the city, and total outstanding debt in the state is $48 billion. As a result, credit rating agencies give low marks to New York State’s bonds, making borrowing more expensive.

Abuse of Public Authorities: The state borrows large sums of money through the public authorities, removing this money from the budget process completely. Public authorities, funded by the state but outside of the control of voters, have increased their debt by almost seven-fold over 20 years. The 18 largest authorities now have about $120 billion in outstanding debt.

These practices are symptoms of a culture that discourages good fiscal practices in the name of political expediency, says Fortuna. They affect not only the fiscal health of the state itself, but also local governments that are forced to assume greater responsibilities as Albany increasingly shifts the burden for expensive programs onto them.

The state’s dysfunction has become the subject of much attention in the past year. Good government groups, the press, and lawmakers themselves have called for changes in the way the state’s affairs are run. These reforms have not only dealt with the budget process – everything from the non-competitive nature of elections to how committees work to the way lawmakers vote on bills has come under criticism. But with a string of late budgets 20 years long (broken this year), the budget process ranked high on the list of issues to confront.

BALLOT QUESTION 1: PROPOSED STATE BUDGET ADMENDMENT

To address problems in the state’s budget process, legislators and some good government groups are backing an amendment to the state constitution, which will be put to voters this November. While this does not directly require anything specific in terms of financial management, its proponents hope that it will encourage more responsible practices through transparency and accountability.

The main provision transfers power over the budget from the governor to the legislature. Currently, the governor creates an executive budget that lawmakers have limited powers to change. Under the proposed amendment, if no agreement is reached on the budget by the beginning of the fiscal year, then a contingency budget based on the previous year’s budget would go into effect. This would automatically become the basis for the new budget, and the legislature would have more power to amend it. Other provisions would establish an independent budget office whose members are picked by the legislature, and make expenditures that are currently not part of the regular budget part of general budget negotiations.

Supporters of this proposal (in .pdf format), which include good government groups Common Cause and the New York Public Interest Research Group as well as many legislators, say that this amendment will give the public more information about what officials are doing, making them more accountable. It will also bring the balance of power between the governor and the legislature more in line with that of other states, they say, and make sure the budget is on time. The overall effects, they say, will be modest, but will lay the foundation for future reforms.

Critics of the amendment believe the effect will be more profound (download video clip). Among the opponents of the proposal is Citizens Union, (whose sister organization, Citizens Union Foundation publishes Gotham Gazette), the Citizens Budget Commission, the Manhattan Institute, and the Business Council of New York State.

Instead of guaranteeing an early budget, they say, the amendment gives lawmakers a reason not to negotiate with the governor until after the budget deadline, at which point they will have much more power. Had lawmakers been given such power in 1975, some say, upstate legislators would have kept Governor Carey from funding the Financial Emergency Act. Today, they say, this increased power will encourage lawmakers to spend money freely.

While they question the reform’s potential to make a positive impact, critics of the amendment do not question the need for change itself. Almost no one believes the state is handling its financial affairs sensibly.

“Change is very, very badly needed,” said Fortuna.

THE FISCAL CRISIS OF THE 1970s AND THE FINANCIAL CONTROL BOARD

- The Fall and Rise of New York by Felix Rohatyn

- The Coming Emergency and What Can be Done About It by Felix Rohatyn

- A Coalition from City, State, National Levels is Needed to Help new York Overcome its Fiscal, Social Crisis by Felix Rohatyn (video clip)

- Gotham’s Fiscal Crisis: Lessons Unlearned by Fred Siegel and EJ McMahon

BALLOT PROPOSAL FOUR: PROPOSED CITY CHARTER REVISION

NEW YORK STATE’S DYSFUNCTIONAL GOVERNMENT

- Albany’s Dysfunction by Gotham Gazette

- New York State’s Fiscal Condition by State Comptroller Alan Hevesi (in .pdf format)

- The New York State Legislative Process: An Evaluation and Blueprint for Reform by the Brennan Center

BALLOT PROPOSAL ONE: PROPOSED AMENDMENT TO STATE CONSTITUTION

- Text of Ballot Proposal One

- Overview by the Rockefeller Institute

- Vote YES on Budget Reform: The November 2005 Budget Reform Announcement by Common Cause/League of Women Voters/New York Public Interest Research Group(in .pdf format)

- The Runaway Spending Amendment by the Business Council of New York State

- Breaking the Budget in New York State: What’s at Stake in November’s Referendum by Manhattan Institute (video clip)

Mayoral Issue Grid: Finance

FINANCE

New York City’s annual budget will pose a problem for the next mayor. Experts project that the city will face a $4.5 billion deficit in each of the next two years. If the mayor cannot reduce spending, he or she will be forced to raise taxes or generate revenue from fees, fines, or tickets. The property tax is the only tax the mayor and City Council can raise without the approval of the State Legislature.

To reduce the city’s projected budget deficit, Fernando Ferrer says that he will eliminate loopholes in the tax code that he says costs the city $2 billion a year. He also promises to fight for more funding from Albany, particularly Medicaid payments. Ferrer also believes that the commuter tax should be reinstated, which would require the approval of the State Legislature.

While Ferrer says he will not raise taxes to balance the budget, he has proposed a stock transfer tax to help raise $1 billion for education.

Ferrer outlined a property tax rebate plan that would "offer a $100,000 property tax exemption to the approximately 600,000 New York homeowners of coops, condominiums and 1, 2, and 3-family homes valued under $800,000. Every qualified homeowner whose home is valued at $100,000 or more would automatically enjoy $973 in savings. Meanwhile, homeowners with homes valued above $800,000 would continue to receive the $400 rebate."

Renters would also receive relief. Under the HOPE plan, Ferrer would provide "an average annual benefit of $295 to renters living in rent-regulated units who have a household income below $60,000 and at least one child under the age of 18."

Michael Bloomberg says that the city’s budget can be divided into two parts: the spending that the city controls and the spending mandated by the state.

Bloomberg argues he has taken steps to reduce the budget where he can, cutting $4 billion from the budget and reducing the city’s workforce by 15,000 employees.

The city’s projected deficits, he says, are a result of things out of the city’s control, like Medicaid and pensions. He supports Medicaid reform and worked to reduce pension costs.

Although he raised taxes in the past, Bloomberg opposes increases in the income taxes or a tax on Wall Street stock transfers.

RELATED ARTICLES:

- 10 Budget Choices Facing The Next Mayor

- The Mayoral Candidates on Budgets, Taxes and Spending (Forum)

- $50 Billion Budget -- A Shortsighted Use Of Surpluses

- Budget Transparency After The West Side StadiumÂ