Fighting Poverty

Disconnected Youth

David Jason Fischer

In recent years, public and government attention has begun to focus on New York City's "disconnected youth"—young residents between the ages of 16 and 24 who are neither in school nor working. A January 2005 report by the Community Service Society of New York estimated that nearly 170,000 city residents met this description; other measures that include unemployed young people who are actively looking for work peg the number above 200,000.

In recent years, public and government attention has begun to focus on New York City's "disconnected youth"—young residents between the ages of 16 and 24 who are neither in school nor working. A January 2005 report by the Community Service Society of New York estimated that nearly 170,000 city residents met this description; other measures that include unemployed young people who are actively looking for work peg the number above 200,000.

As is true in general for those in poverty, disconnected youth are not a uniform group. Some became disconnected when they dropped out of high school; others might be struggling to raise their own children; still others contend with physical or mental health problems or other barriers to education or employment. Roughly half have at least completed high school or a GED.

Given the differences in life circumstances, educational attainment and work readiness among the disconnected, there is no single-bullet strategy for reconnecting them to school or work. For many, high school or GED completion is the goal; others, particularly those with high school degrees and family responsibilities, are more likely to be tracked toward job readiness and employment. Unfortunately, the combination of severely limited public resources and bureaucratic confusion among numerous city agencies and programs has led to very small numbers receiving services: a 2005 report from the Young Adult Task Force estimated that fewer than 10,000 disconnected young New Yorkers were reached by city programs.

The Mayor’s Commission for Economic Opportunity identified “young adults,” including disconnected youth, as one of three groups to target for poverty alleviation. Its recommendations include expanding the alternative-education programs and settings now offered by the Department of Education, such as the Learning to Work program and Young Adult Borough Centers; increasing and strengthening “school-community collaborations” that combine education and community service to help keep youth connected; making available more programs that help young adults transition from GED attainment to college; and focusing on the most vulnerable groups -- ex-offenders and young people aging out of foster care -- with a range of services.

My organization, the Center for an Urban Future, noted in a May 2006 report that the problem of disconnected youth also creates a tremendous opportunity for New York City. As pending Baby Boomer retirements create a new and urgent need for workers in key New York City industries like health care and construction, we can work with stakeholders in these and other industries to create training curricula and career tracks that can reconnect young New Yorkers to jobs that will benefit all city residents.

David Jason Fischer is the project director at the Center for an Urban Future, a think tank focused on issue of economic development in New York City.

Lifting Children Out of Poverty

Donna Lawrence

Fifty percent of the children who are born in New York City today are born into poverty. That is a really frightening statistic. Once children are born into poverty it’s very hard to lift them out.

So, we need to ring the alarm on that alarming number. This report, this commission, is a good first step.

As a blueprint, it’s great. It sets out a framework and covers the critical areas for children and families. The fact that the mayor has done this and is taking leadership is a good signal. But the specific recommendations are going to be key.

For example, the report talks about providing health insurance to children who are uninsured. In New York City, there are about 300,000 children who do not have health insurance, and about 75 percent of those 300,000 are currently eligible for it. So it is good that the mayor recognizes that that children should get health insurance, but the plan does not go into any detail about how he will do that.

We need to know how he is going to reach those kids, what kinds of mechanisms will be put in place to insure that those kids don’t lose coverage and how to simplify the system so that families can get coverage and maintain that coverage.

The Children’s Defense Fund is trying to bring together the food stamp application with the health insurance application. Any child receiving food stamps should be eligible for health insurance, but there are a huge number of kids who get food stamps who don’t get health insurance and vice versa. This is very technical. A lot of federal regulations would need to be waived to bring those application processes together. The mayor talked in broad strokes about trying to bring the systems together. What we would want to see in six months is how far he has gone.

We need to look at things like enrolling children in health insurance at the time they’re born and enrolling parents. Now, when a mother who is uninsured comes to the hospital to give birth, there is no mechanism to enroll her or her children into health insurance.

The childcare issue is critical as well, and it’s good that the mayor is addressing it. To get mothers to go out in the workforce, we need to insure they have quality childcare. The challenge is going to be finding physical facilities. Where do we build these childcare centers, how do we get more programs up and running?

This report is a good first step. There is nothing like a mayor taking leadership on an issue like this, but he has got to keep the momentum going and make sure that the details that are filled in meet the overall recommendations.

Donna Lawrence is executive Director of the Children's Defense Fund-New York.

What Government Should – And Should Not – Do

Heather Macdonald

The government should focus on doing the things it can do and recognize what it cannot do. The dismal legacy of the War on Poverty, which destroyed the black family to the misery of generations of children, suggests that government has very little capacity to engage in what sociologist Nathan Glazer has called “social uplift.”

Government can, however, create the backdrop for individual success. New York should become the opportunity city by creating the most efficient public services in the country — the best roads, rails, communications services and parks — that allow all individuals to seize opportunity and to better themselves.

New York can become much more economically vibrant by cutting taxes and ineffective social programs that only enrich social workers. The tax burden in New York prevents many entrepreneurs from opening businesses here and creating more and better paying jobs. As Mayor Bloomberg himself says, the best antipoverty program is a job. But as long as the middle class is priced out of the city, our job growth will continue to lag far behind the rest of the country.

New York schools should be unfailingly rigorous and demanding; students should be drilled in spelling, writing, and their multiplication tables. Children should graduate not just with academic skills but also having learned to control their impulses and to show respect for legitimate authority. So far, our schools are far from achieving those goals, in large part because the educational bureaucracy remains in thrall to the knowledge-crushing nostrums of progressive education.

Government is responsible for public safety, and here, New York leads the entire country. Mayor Bloomberg and the New York Police Department come closer everyday to ensuring that residents of every neighborhood enjoy the right to safe streets.

What government cannot do is create personal responsibility and drive in individuals. Yet that is what Mayor Bloomberg is attempting to do by paying people to send their children to school or to keep medical appointments. This payment system creates a very odd situation for the long term, as well as the short term. Will the recipients ever be weaned off their payments? The entitlement mentality will inevitably suck in a larger and larger range of paid-for activities. Not just attending classes, but refraining from hitting your teacher, not bringing a gun to school, showing up for an exam, bathing your kids and feeding them -- all will be candidates for a bribe. How will the city choose which individuals to pay and explain to those it is not paying why they should act in their self-interest for free?

Finally, the single most effective way to reduce child poverty would be to restore the norm of marriage to the inner city. Children growing up in single parent homes are five times as likely to be poor as those raised by married parents. They are also many times more likely to fail in school, become juvenile delinquents, suffer mental problems, and, for girls, become teen mothers. Restoring marriage as the norm for raising children does not lie within the power of government. But the mayor can call on private groups to campaign for such a change, and put his own considerable rhetorical stamp on marriage. If successful, such an initiative would be the most important social change in a century.

Heather Mac Donald is a contributing editor at the Manhattan Institute's City Journal.

Don't Forget Those Who Aren't Working

Ketny Jean-Francois

I am one of the 400,000 New Yorkers on public assistance. I am also one of the 13,000 people in the city's Work Experience Program (WEP), administered by the Human Resource Administration. For over a year, I have been stuck doing dead-end and unpaid work. Each day I have to pull weeds from the streets and clean toilets. I do not receive a wage, benefits or a title in exchange for my labor. Instead I receive a public assistance grant. I am forced to do work that does not give me any experience to further my employment prospects. I am interested in entering the health care sector but am currently assigned to the Sanitation Department. Even if I wanted a full time job in the Sanitation Department, there is no pathway from WEP into a paid job at the Sanitation Department. This is the same for most city agencies with WEP workers.

The idea of the Commission for Economic Opportunity is a good and necessary one. But so far it is not clear how the commission’s new report will actually change the lives of people like me. It does not target the unemployed or public assistance recipients, overlooking some of the worst off in New York City.

To her credit, Deputy Mayor Linda Gibbs, who oversees 11 city agencies including the Human Resources Administration, seems interested in discussing the challenges faced by public assistance recipients. Here are a few things I think the agency should do:

First, caseworkers must be re-trained in screening clients for employment and training. This screening should consider past employment experience and current interests, and should be used to place public assistance recipients in employment and training programs that will help them develop skills and access jobs that they want.

Second, the city should expand the paid transitional job programs, such as the Parks Opportunity Program, to all city agencies. This program should include different job types and positions to meet the varied interests and career aspiration of participants.

Third, as is being proposed by the commission for other populations, the Human Resources Administration should create career ladder training programs for public assistance recipients. This would enable us to get onto the first rung of the ladder and out of the revolving door of the public assistance system.

Fourth, the Human Resources Administration should work with other city agencies so that public assistance recipients can benefit from workforce development resources and programs targeted at the working poor.

Overall, while cost-efficiency tells the commission to focus on programs and populations where success is most likely, social justice requires it to not forget those of us most in need.

Ketny Jean-Francois is a member of Community Voices Heard, an advocacy organization composed of low-income New Yorkers. She lives in the Bronx with her three year-old son.

Strategies to Create Jobs

Bich Ha Pham

The establishment of the New York City Commission for Economic Opportunity and the issuance of its recent report are promising developments. The recommendations of the economic opportunity report that were particularly encouraging in regards to the adult working poor include improving and expanding benefits that support work along with ACCESS NYC (a web-based pre-screening tool for over 20 city, state and federal benefit programs), and increasing access to training for those who are working.

As the city looks to implement the strategies in the report, officials can look to a number of promising and model programs from around the country that have raised earnings and family income. These include wage supplement programs that provide cash payments on top of earnings from wages in order to raise an individual’s income to a certain level. That level can be a targeted percentage above the poverty level or a living wage level.

The transitional jobs program for one-time offenders contained in the report can be expanded to include all job seekers, including welfare participants, who along with people who have recently left welfare comprise a segment of the city's working poor. As it implements the report's strategies, the Human Resources Administration should try to provide opportunities to increase access to education and job training, including vocational job training and vocational and educational programs at community colleges.

Lastly, though it may seem like a minor part of the report, the city should not promote policies that imply that working poor people and the poor have behavioral problems. Low-wage, part-time jobs with little or no benefits are proliferating in our city and country. Consequently, so are the working poor. People are poor, not because of poor behavior, but because of a lack of jobs adequate to sustain families and of the vocational training and college education needed to get those jobs.

Bich Ha Pham is executive director of the Hunger Action Network of New York State

Barriers to College

Lynne Weikart

Though the Bloomberg report recognizes that college is an important way out of poverty, it does not address many of the obstacles that keep New Yorkers from getting a college education.

Because of structural, cultural, financial, and political barriers, millions of young people do not even contemplate college, are unprepared to attend the college of their choice or struggle to complete their studies. And those who do finish college often find themselves overburdened with debt. A new “report card on higher education,” by the National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education found that, for many American families, college is becoming less affordable. Whereas Pell grants for low-income students covered 70 percent of a year’s cost in higher education in the 1990s, they now cover less than half.

The report gave New York a failing grade for affordability. In 2003, City University Chancellor Matthew Goldstein stated that almost half of CUNY students came from families in which neither parent had attended college and that 40 percent had adjusted gross incomes of less than $15,000. The cost of attending public universities and community colleges in New York represents nearly half of a low or middle-income students’ annual family income. New York does have tuition assistance but that alone does not solve the problem since New York State is investing less and less in higher education and depending more and more on tuition for revenue.

Other New Yorkers are legally precluded from attending college, since most people receiving public assistance are required to work and have no time to attend a four-year college program and do what they need to do to continue to receive their benefits. Race, ethnicity and citizenship status often affects a student’s ability to even contemplate higher education.

Moreover, recent studies suggest that policies adopted by federal and state agencies as well as institutions of higher education have discouraged low-income and minority students from attending or completing college. These practices include admitting low-income students but denying them meaningful financial assistance or conversely, encouraging wealthier, higher achieving students to attend a particular college by offering tuition discounts.

In New York and throughout the nation, the transition between high school and college is totally inadequate. Many high school students have an alarming ignorance of what academic and career avenues will be open to them after graduation. A few schools have adopted strategies to address this issue. We need to study these college readiness strategies and pay more attention to the issues of access to and funding for higher education.

Lynne A. Weikart is a professor at Baruch College School of Public Affairs

Tough Times for Seniors

Bobbie Sackman

Twenty percent of New Yorkers over 65 live in poverty, more than twice the national average. The typical elderly New Yorker living in poverty is a woman, minority, over the age of 75, living alone. Social security provides 80 to 90 percent of her income.

Unfortunately, the number of elderly people living in poverty looks like it will continue to increase dramatically. Growing numbers of minorities are reaching retirement age already poor – or near to it. Middle class seniors are moving out of the city, while the number of poorer elderly immigrants is increasing.

Unfortunately, the number of elderly people living in poverty looks like it will continue to increase dramatically. Growing numbers of minorities are reaching retirement age already poor – or near to it. Middle class seniors are moving out of the city, while the number of poorer elderly immigrants is increasing.

For the first time in history, the fastest growing segment of the city's population is people over 85. Old age brings with it declining income and wealth. Nearly 25 percent of all households headed by the elderly in NYC have incomes below $10,000, according to the census. Thousands more are near poor, which in New York City means having about $3 a day left for expenses after rent and food. A significant number of elderly New Yorkers spend over half of their income on rent. The Food Bank reports that 25 percent of people utilizing soup kitchens and emergency food banks are seniors, and that proportion is increasing.

If the city is going to address poverty in a comprehensive way, here are some things it should do to help poor seniors.

• Strengthen community-based services helping seniors to "age in place" in their homes and communities. These include senior centers that provide nutritious meals and social services, accessible transportation, affordable housing, case management to assist homebound elderly, home care, Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities, adult day services for people with Alzheimer’s, and caregiver support services.

• Help seniors access existing public benefits such as food stamps and the Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption Program, which protects seniors living in rent controlled or regulated apartments from increases. Currently such programs are significantly underutilized.

• Advocate for increased Supplemental Security Income benefits from the state and federal governments.

• Create jobs and incentives for seniors who are able to work.

Bobbie Sackman is the director of public policy at the Council of Senior Centers and Services of New York City.

Getting Foster Teens Beyond the System

Betsy Krebs and Paul Pitcoff

Most young people who “age out” of the foster care system at 18 can expect to live in poverty. Too many are not prepared for college and too many end up homeless, jobless, and incarcerated. They lack the financial and educational resources they need to become successful adults.

Young people from foster care have the aspirations and potential to become fully participating citizens -- to work in accounting, design, health care, web design, the entertainment industry. The main challenge is convincing adults around them that these youth can – and must-- take on more responsibility while they are still in foster care to prepare for a future of economic opportunity. The culture of low expectations for teens in foster care and the lack of accountability for their success or failure must change.

The foster care system has been given the responsibility of raising thousands of teens to adulthood, but its primary purpose is to protect children from imminent harm, not bring teens to adulthood. As a result, the services provided by the foster care system for teens are typically inadequate, and do not focus enough on future planning as a way for the young people to rise above poverty.

The city has to set high expectations for foster care teens and give them the tools, skills, and education to make the contributions that they can for our society.

The teens themselves can speak most passionately and articulately about what they want for their lives--not just today but for the future. If given responsibility, education and opportunities, they are the best advocates for themselves. And thousands of dedicated and experienced professionals in the foster care system can help lift teens out of poverty if they are given the support and tools to treat each teen as an individual with potential.

But, if we are to be successful in helping foster teens avoid poverty, the broader community must be involved. Leaders from the private sector, experts on higher education, national service, the arts, etc. must get involved -- whether it means giving advice to individual teens, providing scholarships and internships, or participating in policy discussions about preparing teens for adulthood. We all should share in the challenge and responsibility for helping young people in our custody escape poverty and achieve economic opportunity.

Betsy Krebs and Paul Pitcoff, co-founders and directors of Youth Advocacy Center, are authors of Beyond the Foster Care System: The Future for Teens, a book about the development of a program that brings teens, the system, and the outside community into active collaboration to increase opportunities for teens in foster care.

To End Poverty Among Immigrants, Address Language Barriers

Chung-Wha Hong

It is almost unimaginable to talk about any aspect of city life without talking about immigrants. Immigrants and their children make up two-thirds of the city’s population, and over half of births in the city now occur in immigrant families.

Immigrants have contributed enormously to our great city by stopping significant population declines, revitalizing our neighborhoods, and fueling our economy with their hard work and entrepreneurial initiative. Yet over half of all New York City immigrants live at less than twice the poverty level.

We think a comprehensive approach to poverty should include several key policies and programs specifically addressing immigrants.

1) Greatly Increase Adult English Classes and Workforce Training Opportunities

While English may not be required for many low-skilled jobs, there is clearly a link between English proficiency and earning power. Over a third of limited-English-proficient immigrant adults live in poverty, far more than the 14 percent of the English-proficient immigrant adult population. Helping immigrants learn English, and providing English instruction through contextualized workforce training programs is perhaps the most important investment the city can make to reduce poverty in New York’s immigrant communities.

2) Eliminate Language Barriers at City Agencies

Language barriers can prevent the immigrant working poor and their families from navigating vital government programs and gaining access to needed income supports to which they are entitled. For example, many immigrants and limited English proficiency tenants are living in unhealthy and unsafe living conditions, and yet over 60 percent do not know that there is a city agency, the Housing and Preservation Department, designed to help them address their housing needs. There is a need for a comprehensive city translation and interpretation system across all city agencies – similar to recent improvements in city schools, hospitals and welfare offices.

3) End the English Language Learner Dropout Crisis

Over half of the city’s school children come from homes where English is not the primary language. Almost one-in-seven of all city students are classified as English language learners, and therefore in need of quality bilingual education, English-as-a-second language, or dual language instruction. These students face the same tough conditions that all students encounter – a lack of quality teachers, overcrowded classes, and insufficient instruction time – but with the added burden of learning English on top of meeting all other State Regents standards.

Over half of public school students classified as English Language Learners drop out, the highest dropout rate of any subgroup of city students. Additional investments must be made in recruiting and retaining qualified ESL and bilingual teachers, increasing extended day and weekend instructional programs, and fully aligning the English language learners language arts curriculum with the mainstream curriculum.

Chung-Wha Hong is the executive director of the New York Immigration Coalition. This piece was adapted from a letter sent in response to the report published by the Commission for Economic Opportunity.

Banking and Poverty

Sarah Ludwig

If you live in a poor neighborhood in New York City, it’s not the pick-pocket or loan shark you need to watch out for. It’s financial services companies – check-cashers, payday lenders, rent-to-own stores, money transmitters, and unscrupulous tax preparers – looking to strip all the assets they can from you and your community.

|

Graffiti in Harlem |

Some estimate that low income New Yorkers pay as much as 10 percent of their income for financial services. Perhaps that’s no surprise, given that many low income neighborhoods of color still have no bank branches, immigrants wiring money to other countries pay as much as 15 percent of the amount sent, and conventional bank mortgage or small business loans are few and far between.

Unequal access to credit and financial services in NYC corresponds crudely to neighborhood demographics Lacking access to fair and affordable financial services, low income neighborhoods are flooded with solicitations for fast cash, predatory mortgage loans, foreclosure rescue scams, and a growing array high cost credit offerings (“Bad credit? No problem!”). This unequal provision of capital access:

• Reinforces residential segregation, limiting people’s mobility and fair housing choice;

• Thwarts local economic development, affecting the viability of small businesses;

• Diminishes homeowners’ equity and appraisal values, and impedes one’s ability to borrow against assets to pay for higher education or needed repairs, or pass along wealth to one’s family;

• Hampers community revitalization, including schools, crime prevention, and health care improvements;

• Impedes immigrants’ ability to gain an economic toehold in this country; and

• Adversely affects one’s ability to build savings and gain economic security.

The pervasiveness of destabilizing, high-cost credit in New York’s low income neighborhoods is reflected back in people’s credit reports, further perpetuating poverty for millions of New Yorkers.

If you’re among the millions of low-income immigrants in New York City, the situation is grossly magnified, since most of the banking world appears at a loss for how to serve you given the morass of anti-terrorist and money-laundering regulations, which have chilled many banks from even opening accounts for many new immigrants.

What can we as New Yorkers do about all this? The reality is that most banking policy matters fall within state and federal level jurisdiction, not the city’s. That said, the city can, and should, be part of the solution. For starters, the city can:

• Ensure a living wage;

• Refuse to do business, invest pension funds, or otherwise enter into contracts with companies that are known to engage in predatory financial practices, or that fail to serve communities equitably;

• Stop partnering with companies like H&R Block to do Earned Income Tax Credit outreach to low income New Yorkers, when H&R Block is a major purveyor of usurious tax refund anticipation loans that target low income neighborhoods of color in our city; and

• Press mainstream financial institutions to accept a broader array of identification for people to open accounts and adopt a policy of not asking people about their immigration status when they seek to open an account.

Sarah Ludwig is the co-director of the Neighborhood Economic Development Advocacy Project.

Implementing the Commission's Recommendations

Betsy Gotbaum

Government has a responsibility to help lift working families out of poverty so they have the opportunity to join the middle class, and I commend the mayor for convening the Commission for Economic Opportunity. But I would also like to raise a few issues and questions.

Will Private Funding Be Enough?

It is to this administration's credit that it is willing to set ambitious goals for the reduction of poverty, but we cannot expect city agencies to do more without additional resources. I applaud the mayor's pledge to raise at least $24 million in private funds to underwrite the commission's recommendations. An influx of private donations will certainly give this new anti-poverty initiative a shot in the arm. But private donations are not necessarily reliable or sustainable over the long term, and it is crucial that the funding to carry out the commission's recommendations be institutionalized so that it outlives the present administration.

Expanding Benefits

The commission's report calls for "improving and expanding benefits that support work." I urge the administration to interpret this as a mandate to adopt tools like the Able Bodied Adults Without Dependents waiver and remove obstacles such as the finger-imaging requirement for food stamp applicants, steps that would help more New Yorkers put food on their tables and bring more federal dollars into the city economy.

Don't Forget Single Mothers

The report also recommends that the city "expand programs that help prepare fathers for job opportunities, skills-building and legal, financial, and emotional responsibilities of parenthood." I, of course, strongly support this recommendation. But in a city where the poverty rate among single mothers is 41 percent and the labor force participation rate for single mothers with no more than a high school education has risen to nearly 58 percent, I would hope that the commission's recommendation could be broadened to include single mothers as well.

Betsy Gotbaum is the public advocate of the City of New York. This piece was adapted from comments she made at a City Council hearing on September 21, 2006.

Â

The Many Faces of Poverty

Tenement House

Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s poverty commission (officially called the Commission for Economic Opportunity) released its long awaited report on September 18, with a slew of statistics and recommendations about confronting poverty. Below, a dozen responses, which offer a glimpse at some of the many kinds of New Yorkers who are poor:

Disconnected Youth

David Jason Fischer of the Center for an Urban Future approves of the commission's focus on young adults, arguing that moving these young adults into steady jobs will not only help them stabilize their lives, but fill a major economic need as well. (Read More)

David Jason Fischer of the Center for an Urban Future approves of the commission's focus on young adults, arguing that moving these young adults into steady jobs will not only help them stabilize their lives, but fill a major economic need as well. (Read More)

A Blueprint for Children

With 50 percent of all children in New York being born into poverty, the mayor’s plan provides a good blueprint for addressing the problem, writes Donna Lawrence of the Children’s Defense Fund. The key, though, is how he fills in the details on health insurance, childcare and other important issues. (Read More)

The Working Poor

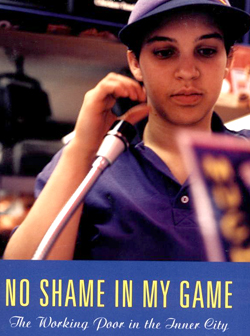

Urban anthropologist Katherine Newman discusses how many fast food workers – one of the archetypical jobs for the working poor – were able to work their way from poverty to the middle class – and why those who couldn't do so failed. (Read More)

Urban anthropologist Katherine Newman discusses how many fast food workers – one of the archetypical jobs for the working poor – were able to work their way from poverty to the middle class – and why those who couldn't do so failed. (Read More)

The Government's Role

Heather MacDonald of Manhattan Institute's City Journal urges the government to concentrate on the few things it can do -- creating rigorous, demanding schools and safe streets --, and stay away from things beyond its capacity, such as forcing people to be responsible parents. (Read More)

New Yorkers on Welfare

Public assistance recipient Ketny Jean-Francois argues that any response to poverty must explicitly deal with getting New Yorkers on welfare into stable jobs. (Read More)

Public assistance recipient Ketny Jean-Francois argues that any response to poverty must explicitly deal with getting New Yorkers on welfare into stable jobs. (Read More)

Helping People Get Good Jobs

As more jobs pay less and offer fewer benefits, the number of poor people increases. Bich Ha Pham of Hunger Action Network says any strategy to reduce poverty must help people get better jobs.(Read More)

Keeping People Out of College

Higher education can help people get out of poverty but, writes Lynne Weikart of Baruch College, a number of barriers, from high tuition to welfare rules, keep New Yorkers out of college. (Read More)

Poverty Among the Elderly

Seniors in New York City are more than twice as likely to live in poverty as the elderly across the country, writes Bobbie Sackman of the Council of Senior Centers and Services of New York City. She explains why and proposes some steps that could be taken to address the problem. (Read More)

Seniors in New York City are more than twice as likely to live in poverty as the elderly across the country, writes Bobbie Sackman of the Council of Senior Centers and Services of New York City. She explains why and proposes some steps that could be taken to address the problem. (Read More)

From Foster Care To Poverty

"Aging out" of foster care often leads to a life of poverty. For that to change, argue Betsy Krebs and Paul Pitcoff of Youth Advocacy Center, the foster care system must change. (Read More)

Immigrants and the Language Barrier

Over half of the city's immigrants at either impoverished or near poor. The major issue that needs to be addressed, writes Chung-Wha Hong of the New York Immigration Coalition, is the language barrier. (Read More)

Over half of the city's immigrants at either impoverished or near poor. The major issue that needs to be addressed, writes Chung-Wha Hong of the New York Immigration Coalition, is the language barrier. (Read More)

The High Cost of Credit

High-interest loans and a shortage of decent financial services in low-income neighborhoods make New York's poor even poorer, says Sarah Ludwig of the Neighborhood Economic Development Advocacy Project. (Read More)

Implementing the Plan

Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum praises the mayor for confronting poverty, but says the issue of funding must be addressed, and public benefits and programs for single mothers should be added as the commission's strategy is implemented. (Read More)

Â

Fast Track From Poverty?

A mayoral commission published its strategy for confronting poverty in New York City on September 18, putting particular focus on the working poor, young adults 16 to 24, and children under 6. Earlier this summer, Gotham Gazette's Reading NYC Book Club met with urban anthropologist Katherine Newman to talk about her work with young, poor fast food workers in Harlem. Such jobs are frequently dismissed as meaningless after-school jobs for teenagers looking for pocket money, or dead end jobs for adults who can do no better. Newman found a much more complicated picture. Below is an edited transcript of our discussion.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Our guest this month is Katherine Newman, who is an urban anthropologist who now teaches at Princeton; she has also taught at Columbia and Harvard. The book for this month is No Shame In My Game, a sort of an ethnography of fast food workers in Harlem, with the intention of examining the experiences of the working poor in urban areas.

One thing that you mention in the introduction to the book, Professor Newman, is that at the time you were writing, policy makers and academics were talking about welfare policy, but the people who were working and still stuck in poverty weren't being discussed.

In the last presidential election John Edwards ran a campaign that was largely based on policies addressing the working poor, and in New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg has also announced that he wants to look at poverty in New York City.

So have things changed? Are people now paying attention to the experience of the working poor?

KATHERINE NEWMAN: I think that people are paying a lot more attention than they once did. In the early 90s when I first got started doing this work, poverty was really synonymous in the public mind and in the world of journalism with people who were out of the labor force, especially those who were persistently attached to the welfare rolls, for whom there was no sympathy, no understanding, and no affection. The working poor were completely invisible in this discussion at the time.

I do think that that has changed, because welfare reform really shredded the safety net that once was represented by welfare, and thrust many people who were high on everybody’s list of the despised into the labor market, into exactly the same kinds of jobs that I focused on.

So it has changed, but there isn’t nearly as much sympathy and understanding as I would have hoped for.

I think that we remain persistently skeptical about people who are out of the mainstream. Where once that meant not working, now we say, "why are those people working at such crappy jobs? What is the matter with them that they are at the bottom of the working heap?"

FAST FOOD WORKERS IN HARLEM

GOTHAM GAZETTE: There are poor people working throughout the country. Why did you decide to focus on Harlem, and why did you decide to pick the fast food industry?

KATHERINE NEWMAN: I was a neighbor in Harlem, and all field researchers want to do their research close to where they live because you spend a great deal of time with the people.

I thought it would be worthwhile for a then-Columbia faculty member to invest some time to study the city that we worked in. And also because Harlem is a historic capital of black America, and black America is what I set out to study in looking at the working poor.

I chose the fast food industry first because I thought that I was going to be studying young people in the labor market; I actually set out to study teenage workers. I discovered subsequently that the labor market was so bad at the time I began the study that teenagers actually couldn’t get these jobs very easily. These jobs were being held down by prime working age adults with families to raise. And that was a shock to me.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Is it your impression that those jobs are still being filled by adults with families to raise, or do you think that the market is better now for teenagers?

KATHERINE NEWMAN: Well, I think that the market fluctuated in the period between the time when I began working on No Shame in My Game and the present. So I followed the people in this book and discussed what I learned about them in a book coming out in October called Chutes and Ladders. In that eight-year period the market became much better. Those opportunities began to open up again, and adults moved on to better jobs, moved up the ladder and into better sources of employment. Then after 9/11, the economy began to run down again, but not nearly to the level it was when I began the project.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Do you think that the experience of the working poor in New York City is different from elsewhere in the country?

KATHERINE NEWMAN: Not enormously different from other big cities. Of course the dynamics change and the population changes depending on the composition of the city. In New York at the time of No Shame in My Game, if you went a few miles outside of the city to Long Island you would sort of see a totally different population in that type of jobs – and a much more favorable wage structure, by the way. It just reflects supply and demand. The teenagers were too affluent there and weren’t interested in these jobs.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: The major groups of workers in your book are African-Americans, Latino immigrants, and Puerto Ricans. Recently, there has been a lot of talk as part of the immigration debate about illegal immigrants taking low-income jobs taking from native-born Americans. Did you find that to be the case?

KATHERINE NEWMAN: I did. In central Harlem, which at the time was entirely African-American, you did see a steady movement of Mexican-Americans, Puerto Ricans and Dominicans into this labor force. This was partly because employers were persuaded that immigrant workers – especially immigrant workers socialized abroad – would be grateful to have these jobs, wouldn’t complain very much, and be more compliant, docile workers.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Did that create tension between the two groups?

KATHERINE NEWMAN: It created tension and friendship both. There was friction, mainly when it came to hiring new workers. So when the African-American workers tried to foster their friends and family members into new job openings, and found that their recommendations weren’t taken as seriously as Latino workers' recommendations, that created friction and caused anger.

But the thing that I found most striking was that people created a community of friends out of the people they worked with. Workers had friendships or relationships with each other; they went to the movies together. The workplace is a great generator of cross-racial contact and friendship.

This was important because lots of young people in the workforce would take tremendous hazing or teasing for taking jobs that required them to wear uniforms and to show a lot of deference to customers. The more hazing that they experienced with their friends on the street or in the neighborhood, the more they drew close to the people they shared this stigma with: their fellow workers. They developed a sense of pride in being a worker, not so much in this job, but in being an employed person. That distinguished them from the people they knew on the street who didn’t have jobs.

THE PEOPLE WHO WORKED THEIR WAY OUT OF POVERTY

GOTHAM GAZETTE: So for the research in this book also for Chutes and Ladders, you followed people for about eight years. Are there any stories that stick out?

KATHERINE NEWMAN: There are many stories that stick out in my mind.

Jamal was an African-American young man, and was about 22 years old when I first met him. [The names Newman uses are all pseudonyms]. He had a common law wife and a young baby. This is a troubled situation; they lost the baby to foster care because of a violent incident that he never really wanted to talk about much. And Jamal looked for better jobs, but at the point I first encountered him only once in his life had he held a job that had paid a living wage: he had in his younger years found a job at an auto factory, that was the best job that he had.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: That was out-of-town?

KATHERINE NEWMAN: Yeah it was where his grandmother lived. This kid came from a pretty tough background, his mother was a heroin addict. And he had to fend for himself at a very young age, from about thirteen onwards. He had to work part-time and earn his own way, as his mother’s addiction got worse, his life got worse and he would run away to his grandmother’s house and she would put up with him for awhile until she got tired of having him. It was a very unstable life.

At the point that I finished No Shame in My Game. I lost contact with him. I looked for him everywhere and then eight years later for the final follow-up that appears in Chutes and Ladders we found him, way out West. And I almost didn’t pursue this lead, because I was so unsure that it could be him. I just couldn’t imagine how Jamal could have ever found himself to where he was. But, there he was, in a small community in Northern California, where he now earns about $30,000 a year. He is married -- not to the person that he was with when I knew him first – has three kids, a good steady unionized job.

Jamal works at a skilled job in a laminating wood factory. So through a long circuitous train of events he found his way to a place where his lack of education really didn’t matter very much. They don’t care whether you have a college degree in a wood factory.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Should we take anything from the fact that he is not in New York City, that he left the city and ended up in a completely different region in the country?

KATHERINE NEWMAN: Well, one strategy for upward mobility is to move where there are better jobs for people who have the characteristics that he had. But, other examples stayed here in New York. Kyesha worked the drive-thru window at Burger Barn. [Burger Barn is a pseudonym for the national fast food chain where the subjects of Newman's book worked]. She was earning 25 cents more per hour than the minimum wage after four years on the job.

Kyesha also had held a job cleaning up around the housing project where she lived in the summer time. She established a good reputation for herself as a good worker and then eventually got hired full-time as a civil servant. Eight years later she is earning about $30,000 a year running the janitorial staff and repair staff in one of the large public housing projects in Harlem.

Kyesha earns a lot of money for someone of her background, and is very motivated to study for advancement in the ranks of the New York City Housing Authority – or may shift over to the New York Sanitation department. If you had told me, when I first met her, that she would have a job that would have any of those benefits, I would have fallen over. But that’s a New York City story, of someone who found her way into unionized employment in the civil service, which has always been an avenue of mobility and security for minorities.

The ability to pursue that kind of chance in life is a function of how large or restricted we make the civil service. Every day we shrink public sector jobs is a day we reduce opportunities for people like Kyesha.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: In Chutes and Ladders you write that a large proportion of people worked their way out of poverty. Do you have a percentage?

KATHERINE NEWMAN: About 25 percent really did work their way out of poverty. About the same number remained more or less where they were. And everybody in between kept ahead of inflation and did migrate to better jobs, but just not enough to make a huge difference in their lives. For that middle group, the fate of their families depends a great deal on their personal relations with other people. If they have partners that are contributing as earners, their families look a lot better. If they don’t, they are still struggling.

KATHERINE NEWMAN: About 25 percent really did work their way out of poverty. About the same number remained more or less where they were. And everybody in between kept ahead of inflation and did migrate to better jobs, but just not enough to make a huge difference in their lives. For that middle group, the fate of their families depends a great deal on their personal relations with other people. If they have partners that are contributing as earners, their families look a lot better. If they don’t, they are still struggling.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: How much do you think these two factors make a difference in the changes: the changes in the economy, and just the fact that they are older and have more experience. What should we make from these changes?

KATHERINE NEWMAN: Some ability of upward mobility would accompany getting older and having more experience. But in a very slack labor market it won’t pay off very much. If there aren’t better jobs to go to – or the better jobs are being held by people with much better credentials – then you’ll still get this population at the bottom bumping up against a ceiling. It’s not a glass ceiling; it's more like a brick wall. But what happened in the late 90s and the early part of 2000 and 2001 is that we had record tight labor markets, better than we’ve seen for forty years. It was just about the best economy we’ve seen in generations, and might be the best that we are going to see in some time to come. That did open up opportunities for people.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Were there any things that the people who succeeded had in common?

KATHERINE NEWMAN: They had ways of taking care of their children that were stable, either because they had good day care, or because they had relatives who could share the burdens. This meant that they had stable track records in the labor force. It is very harmful for women in particular to have unstable ties to the labor force.

They did gain experience and gain references by virtue of having the jobs that they had before.

They had contacts or people who could give them advice about where to find better jobs. And sometimes those contacts were as simple as running into someone who had a job as a porter in one of the high-rise buildings and he said 'hey there is an opening here'.

There is nothing like a union card to give you a higher wage, even for a job that does not require a vastly higher skill set.

The union story is very important too. Not just civil service, but private unions also, which have traditionally not been that open to minorities. When they are, there is nothing like a union card to give you a higher wage, even for a job that does not require a vastly higher skill set.

One of the characters in the book, Reynaldo, this was his experience. When we first met him he was working at Burger Barn and doing a lot of other things on the side. His father had this kind of business as an unlicensed contractor. Reynaldo’s dad had taught him how to do wiring and plastering. He could renovate an apartment on his own, even though he never had any credentials in a union. Eventually he found a job as a unionized porter in an East side building. His wages jumped threefold, and he had the benefits that often come with union jobs.

DIFFERENT PATHS FOR MEN AND WOMEN

MARTHA SOFFER: Was there a statistical difference of how successful men and women were rising out of poverty?

KATHERINE NEWMAN: Their pathways for mobility were different. The men were more likely to get blue-collar, unionized jobs. Women did better in the service industry, in part because women tend to get more education.

So we see men and women not necessarily rising up in unequal numbers, but in different routes. Women are the ones who are likely to be burdened with childcare obligations, and if someone is going to stumble for family reasons, it almost always is going to be a woman. But that said, I was struck by the consistent contribution that men made to their children even if they didn’t live with them.

In general, women are outpacing men in their enrollment in higher education across the country in all racial groups. The numbers are much more skewed in the African-American community. But this is a serious problem across racial lines, because the kinds of jobs that permit you to earn a good living because you're strong are disappearing in large numbers, or are being exported overseas. This is a big policy issue that we need to address, because we are losing a lot of young men.

POVERTY AND PUBLIC POLICY

GOTHAM GAZETTE: What are some of the other policy issues that should be addressed?

KATHERINE NEWMAN: Well, I don’t think of myself as a policy expert. But here are some things that matter:

First; I think access to higher education is absolutely critical. That’s an issue where I think we are marching backwards very quickly, including here in New York City. The City University of New York has always been a gateway for low-income families and immigrants into higher education, but every time that we raise tuition by $1,000 there are 40,000 people who drop out of the university. It's really penny wise and pound foolish to do this.

Tragically, many people in No Shame in My Game were very well aware that they needed more education. They just didn’t have the money. They were constantly enrolling in school, and then dropping out. Some of them took ten or fifteen years to complete their bachelor’s degree. To their credit they stuck with it. But they would have been able to have access to much better employment, if they could have done that faster. But our financial aid policies are not set up to accommodate adult workers. We don’t provide childcare to make it possible for adults to continue school.

Second, funding training is very important as well. One of the things that I wrote about in the book, which subsequently got picked up by some mayor's offices around the country, was trying to provide better linkages between employers. An employer who has a crew of fast food workers cannot do that much for them. There are only a certain number of people that you can push up into management. But someone who has proven themselves in a job like that – which is a tough job that requires a lot of stamina and a lot of sticking power – should be able to connect to a better job. If employers were able to do this through what I call an employers consortium, a kind of a trading link between employers who only have minimum wage jobs to offer and employers who have more skilled better jobs to offer, I think there would be benefits for both. For the low wage employer, it gives him something to hold out to a potential worker as a reward for sticking with the job, which is typically quite high turnover.

For the employer that has the better jobs to offer, there are benefits as well. It is amazing to me how difficult it is for employers to judge the people who come before them as job applicants. What do they know about them? Actually, surprisingly little, one of the reasons why prejudice runs as rampant as it does.

Third, we certainly need to do better in our public schools. I give a lot of credit to Mayor Bloomberg for this. There was no serious effort going on before and nothing to look forward to improvement.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Do you think that raising the minimum wage makes any difference?

KATHERINE NEWMAN: Well, everyone is in favor of raising the minimum wage, myself included. But, the minimum wage would go to my seventeen year old son, who doesn’t need an increase in the same way that Kyesha needs one. We call this a blunt instrument. The value of the blunt instrument is that it is politically popular. It is politically more sustainable, and this is one reason why Republicans actually vote for increases in minimum wage.

A more targeted and efficient way to deliver money to poor workers is the Earned Income Tax Credit. This credit is not given to everyone; my son would not get it, because the Earned Income Tax Credit is only available to families with children who are on the very bottom of the labor market. It is targeted at working poor families. Now that means that it is more efficient, in the sense that it is delivering resources to the very people that we think need them the most. But, very efficient, very targeted benefits are politically less sustainable. The Earned Income Tax Credit has actually been pretty popular – it was a Nixon administration idea. Periodically though, conservatives attack the EITC and argue that there's fraud involved, and try to start to dismantle it if they see the uptake rate in EITC growing.

TOM MCFALL: When it comes to people from inner cities that have a difficult time getting employment, many, especially males, have been incarcerated. Then there are the mothers who are losing the welfare benefits. Do you find that there are bridges to these groups as a route to get to mainstream jobs?

KATHERINE NEWMAN: I was not focused on the incarceration question, but that is a crucial policy problem, and we are shooting ourselves in the foot with respect to this issue.

The employers that I studied were more positively disposed towards people who had prison records than most employers, and they were willing to make use of wage subsidy programs that others have rejected entirely. But I can’t really advocate that as a major policy because I know that in general it hasn't been very successful.

Honestly, we are building a time bomb there and it's not just a problem for men who have been incarcerated; it’s a problem for the neighborhoods in which they are being released. Something like 600,000 men a year are released from prison, and they are settling in very poor neighborhoods where the options for employment aren’t very rosy, and where we can probably expect high rates of recidivism. We have cut training budgets, and we have made it more difficult for them to pursue higher education, while incarcerated. All of this is just stupid beyond belief.

We cannot afford continuing to expand the prison system as we have been. It's actually economically unsustainable, and that is probably the only thing that is going to help reverse this. The states that pay attention and invest in this problem are going to eventually be shining beacons that the rest hopefully will turn to.

Time-limited welfare was something that I was worried about when I came to the conclusion of this book, because I thought that this would lead into a huge influx of people into the labor market who had much of the same characteristics as the people that I was studying. I was starting out in Harlem neighborhoods with high unemployment, I thought this is just going to get worse. But, what Chutes and Ladders shows is that this was not the case, because the economy roared in the late 90s. It was able to absorb not only people coming off of welfare, but young entrants into the labor market. We have seen a massive number of women going into the labor force, especially women with young children. If that was what we were trying to accomplish, then welfare reform worked very well. What we didn’t accomplish was a great decline in poverty. What we did was exchange welfare dependent poverty for working poverty.

Now is that a good thing or a bad thing? At the risk of alienating all of my politically correct friends, I actually think it's a good thing for people to be working. People who work for a living feel better about themselves. You cannot be a non-working able-bodied adult in this society and have a shred of honor. It just doesn’t matter whether you are an uptight right-winger or a woman on welfare. The women on welfare had exactly the same point of view. And once they took jobs – even if they were workfare jobs – they felt better about themselves.

While I am convinced that work is beneficial for the adults, I am not convinced that it is beneficial for their children. The consequence of going to work for long hours is to leave your kids often in substandard childcare settings or just unsupervised after school. We may see the next generation repeat the problems of the parent generation, even if the parents look better.

So one of the questions that I am concerned about is that when we formulate policies we tend to think about them in these little silos: the adult woman on welfare, the young man who is incarcerated. We don’t think about what policies moving in one direction will do to the other people in the households who are affected by the consequences.

EXPLOITATION OR OPPORTUNITY?

JOHN GUZMAN: I told a friend about the book, and I told him the title, and he said "well, there's no shame for the worker, but there's shame for the owner." But I think the owners fared well in this book.

KATHERINE NEWMAN: I have an interesting story to tell about that. When I first began this research, I had the cooperation of the franchise owners whose businesses I was studying. When the corporate level eventually found out, it was alarmed. I found myself in corporate headquarters, because they actually wanted to put a break in this study. It turned out that they couldn’t, because franchise owners are actually independent business owners and they could do whatever that they want. But I found myself in this fancy big operation with these corporate big shots. I told them that at the end they would be really sorry [that I didn't use the] real name of this firm. My observations suggested that this was a far more positive work experience, and that the employers themselves were more honorable people than most readers would ever think.

Doing business in the center of a very poor, high crime community is very risky. It requires a certain kind of almost missionary zeal. You could be on Long Island with the same business and make more money and have an easier time. You wouldn’t need all of the security guards and you wouldn't have all the problems that you face on the shop floor. These employers had elected to be in Harlem because they were committed to Harlem.

Now, I don’t want to say that they were saints. They were business people, and they were looking to make a profit. But they were much more invested in the lives of their workers then most people realize. They helped people get eyeglasses; they helped people get ID; they cosigned leases; they were offering young people money if they got good grades; they paid for their schoolbooks. A lot of the people think that they are totally exploitative and that the owners are despicable people. I went into this with many of the same forms of skepticism, and I came out thinking it's too bad we don’t have a lot more people like this.

Very often these employers were the only ones who were paying a good deal of interest in the school performance of these kids. So one of the things that I argue in the book is that really contrary to common wisdom school and work are not antithetical to one another. These young people were doing better in school than the young people who weren’t working, because the discipline that they learned on the job and the oversight the business owners and mangers exercised over them was having a positive effect on their school performance.

I think it would enormously helpful if public officials approached employers and encourage them to do these things. Probably many more employers would be willing to do the kinds of things these men and women were doing if they knew they were worthwhile. You get a better labor force if you connect with people beyond the wage you're paying them – which isn't a very good wage – offer them incentives, and show an interest.

MARTHA SOFFER: You have to keep in mind that the non-franchise business owners in poor neighborhoods tend to hire illegal aliens. It's only the franchises with the corporations behind them that have to hire documented people. So you have two distinctive business communities.

KATHERINE NEWMAN: I did not study undocumented workers. I am sure that there is less scrutiny over them and that is maybe a more shadowy labor market. Without studying those employers I wouldn't want to hazard a guess how they conduct their businesses. I must say that I was surprised at what I found in the businesses that I did study. And that has taught me as a social scientist that you shouldn’t prejudge anything. It's all open for investigation.

Â