An Outer Borough Drought

This story was done through a partnership between The Huffington Post's Eyes and Ears citizen journalism program and Gotham Gazette. Gotham Gazette reporter Courtney Gross wrote the piece using stories from New Yorkers gathered through The Huffington Post and Gotham Gazette. Sign up here to join Huffington Post's citizen journalism team covering New York to be part of more of these stories.

Fruit stands are Manhattan's new hot dog vendor, minus the mustard and ketchup.

Their street corner takeover has sparked some New Yorkers, like Upper East Sider Jamie Kayam, to carp that their neighborhood is oversaturated with apples, bananas and overly ripe white cherries.

"In NYC, buying fruits and vegetables has never been easier!" Kayam wrote in an e-mail to Gotham Gazette and The Huffington Post. "When recently discussing life in the city with some friends, a key complaint that came up was that there are too many fruit stands in Manhattan!"

Across the river, Kayam's plight might be a blessing.

The Upper East Side has one of the highest concentrations of food retailers in the city, according to the Department of City Planning. The neighborhood ranks third in the number of grocery stores per capita, boasting more than 22,000 square feet of strictly supermarket space per 10,000 residents, according to the department.

But out of Manhattan, greens get elusive. In the South Bronx, residents have about half of that supermarket space. In Brooklyn's Bedford Stuyvesant, 82 percent of retailers are unlikely to sell fresh fruits and vegetables, and in some areas of Upper Manhattan that number increases to 90 percent, according to city planning.

The Huffington Post and Gotham Gazette asked you how far you travel to get fresh fruits and vegetables. Many of you said veggies are ripe for the taking in your neighborhoods. But a majority of those of you who responded, almost two thirds, live in Manhattan, brownstone Brooklyn or other affluent areas of the five boroughs.

Those outside of these areas may not find a fruit flood, but a produce desert.

|

|

|

|

|

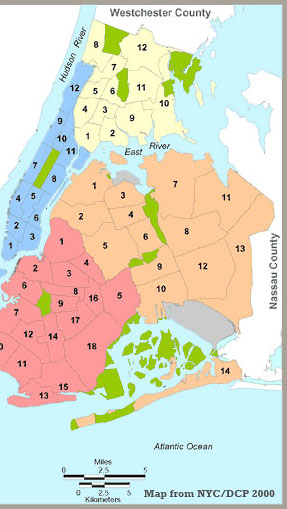

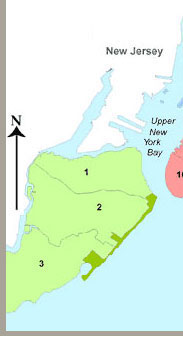

This map uses data from the city's Going to Market report released last year. Rollover a district to find out how many supermarkets there are and how that compares to the number of residents.

A Borough Away

Chelsea is an agricultural Atlantis, says resident Steve Panepinto.

"There's a wide selection of fresh fruit and vegetables on virtually every corner not to mention in the half dozen supermarkets that are within three to four blocks of my apartment," he told us. (Chelsea actually has the highest concentration of grocery stores in the city, according to city planning.)

About 100 blocks north it's another story.

"I live in the West Harlem area, and it is incredibly difficult to find quality fruits and vegetables," writes Erin Barker. "It's a big problem. Even when stores have this stuff, it's usually not in good shape -- bruised or not usable. I think it is more difficult in my neighborhood than it is in wealthier areas of Manhattan that have more upscale grocery stores."

Barker, according to the city, is on point. The lower the median income, the harder it is to find fresh fruits and vegetables. (Chelsea's median household income is more than $100,000, while West Harlem's is about $30,000.)

The discrepancy, according to Ben Thomases, the Bloomberg administration's food policy coordinator, explains why the city is targeting areas in Upper Manhattan, central Brooklyn and the Bronx to grow (pun intended) access to fruits and vegetables. It's pushing for produce on the shelves of corner bodegas, has issued 1,000 green cart permits for specific neighborhoods and is now working on financial and zoning incentives to get more supermarkets into certain areas.

"A lot of low-income communities in Upper Manhattan and the outer boroughs were decimated in the '70s and early '80s," said Thomases. "At that time, naturally, a lot of supermarkets left. When the communities were rebuilt, for a mixture of reasons, the supermarkets didn't really come back."

The administration has already kicked off its financial package, which includes tax abatements for new supermarkets and for those that want to renovate or expand. The city will provide a sales tax exemption for anything related to expanding or constructing a grocery store, from cash registers to two by fours. It also is offering a mortgage recording tax waiver.

To root even more supermarkets in needy neighborhoods, the city's Planning Commission proposes to allow developers to build bigger spaces if they include a supermarket in their plans. If a large mixed-use development has a supermarket on its bottom floor, the city will support the addition of the same amount of square feet of residential space, in effect adding thousands of square feet to the structure. City officials say they will also lower the amount of parking spaces required for supermarkets and are allowing larger grocery stores in manufacturing areas. Currently, these zoning proposals are under review and should be voted on by the City Council by the end of the summer.

Getting Fresh Foods

So far, the city is aiming low. A success to Barry Dinerstein, a senior planner at the city's Department of Planning, would be another 15 supermarkets sprinkled throughout the city's highest need areas in the next few years.

That goal is unlikely to alter Keri Roberts's two-mile bike ride from her Windsor Terrace apartment to the "local" Costco.

"My biggest complaint about living in New York is how hard it is to get fresh produce," Roberts, a technical writer and 16-year Brooklyn resident, said.

For many like Roberts, it's not just about proximity, but cost. If you're on a fixed income, the corner bodega's fruits, while close to home, come with an inflated price tag. "It's just so expensive," said Roberts.

So, some New Yorkers walk (a.k.a. wince and make like it's an added health bonus). Oliver Noble, who is on fixed income, travels 25 blocks from his Park Slope apartment to a vegetable market. Last week, he told us, those blocks cut his produce cost at least in half. He got green peppers for 69 cents a pound -- a bargain from the usual $1.99 a pound.

At least for the next few months, the city's green markets can be a summer savior. The Council on the Environment of New York City, a city-affiliated nonprofit, is running 49 greenmarkets this year across the five boroughs, bringing fresh vegetables (at least temporarily) a lot closer to home for scores of neighborhoods, said Sabine Hrechdakian, the council's special projects and publicity manager. Of those, 23 accept food stamps.

But only 18 of the markets are open year-round, seriously depleting the fresh food supply come the colder months.

Hence, the city's new pro-supermarket campaign.

"We recognize a farmer's market does not take an area that is really underserved by fresh produce and make it all better," said Thomases. "They generally operate one or two days a week. People need to shop seven days a week."

People like Michael Paone, a Crown Heights resident who heads to Park Slope's food cooperative for affordable veggies via bike or two subway transfers. Fresh Direct or a quick and accessible purchase at the local bodega is out of his price range, leaving him with little options.

"It's a shame to me that the main place I can afford (monetarily and biologically) to patronize is not in my neighborhood," Paone told us. "One day, soon, I hope this will not be so."

Public Hospitals in Critical Condition

Four clinics are set to shut, four mental health programs in New York City public schools won't be around next year, and three satellite pharmacies are about to fill their last prescriptions.

These are just some of the measures the city's Health and Hospitals Corp. is taking to address a budget hole that could grow to $1 billion in 2010. And more cuts are coming, said corporation President Alan Aviles.

Call it a side effect of being a public hospital system, but the Health and Hospitals Corp. has been consumed by a tsunami of unfortunate fiscal tidings. Several detrimental cuts from the state (the state's Department of Health argues otherwise) and a steady rise in the uninsured, corporation officials said, has forced the 11-hospital network and its scores of outpatient clinics to restructure -- floating the possibility of a consolidation of services and additional clinic closures.

At a City Council budget hearing Wednesday, Aviles said the corporation is grappling with how to close a $316 million budget gap for this year alone. It has already earmarked measures, such as closing clinics in Sunnyside and Springfield Gardens in Queens, a clinic in the High Bridge section of the Bronx and another in Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn, which would save $105 million. Additional budget actions, Aviles said, are under review.

But the corporation faces structural, long-term fiscal problems that its leaders attribute to restructured state Medicaid reimbursement rates, unreliable federal funding streams and a growing population of patients who can't afford to pay. The cuts alone will not remedy those problems.

Dire Straits

No one can deny the city's public hospital system, which sees 1.3 million New Yorkers a year, is in critical fiscal condition.

"HHC has problems in the few hundred million at the moment because of the state cuts, but when you look at its financial plan going out, its problems are in the billion dollar range," said Mark Page, the director of the city's Office of Management and Budget at a recent City Council hearing. "And how that gets addressed in the next few years, I think it's going to be a huge challenge for New York City and HHC."

Not surprisingly, it is difficult to determine who is to blame. The corporation, say officials, is pointing at the state, specifically its revision of Medicaid reimbursement rates and its distribution of federal Medicaid funding streams, including money it received from the federal stimulus package.

The Health and Hospitals Corp. says it lost out.

"The state has discretion with those dollars, and they were largely used for gap closing," said Aviles of the state's own budget woes. "They were certainly not used to offset further cuts (at the Health and Hospitals Corp.)."

With the aim of restructuring its rates for reimbursing hospitals, clinics and doctors for treating low-income Medicaid patients -- a calculation that still relied on figures from the 1980s -- the state, over the course of two years, approved new formulas for the disbursement of Medicaid dollars. The new formulas, according to state officials, would not only bring the reimbursement rates up to date, but also reflect the type of care New York's patients actually received. State health department officials said the state had been overpaying for inpatient care and underpaying for outpatient care as the health industry refocused its concentration on preventative medicine. Under the new rates, say state officials, the corporation could take advantage of higher outpatient rates by moving some procedures to their clinics.

The implication of the new rates, said Deborah Bachrach, deputy commissioner for the Office of Health Insurance Programs at the state Department of Health, was a hospital would get paid more if it did more. The state, she said, should not pay the same rate to clog a nosebleed that it pays for cardiac care.

"Our first obligation is to get people covered," said Bachrach. "And the second obligation is to buy the right care in the right setting at the right price."

The Health and Hospitals Corp. does not see the revision that way. Aviles told the City Council that the corporation would lose $45 million in Medicaid funding this year, $109 million in the next fiscal year and $150 million in fiscal year 2011.

Much of the corporation's funding comes from two other Medicaid federal funding streams, which are distributed by the state. This year, the corporation has received about $416 million so far from these streams, according to corporation officials, half the annual $838 million it received, on average, over the past five years. More is likely to come from the federal government later this year, Aviles said.

The state does not contribute to at least $300 million of that Medicaid funding. Half is from Washington, and the other half is from the city.

The corporation's primary patient population is poor and uninsured, and under its charter, it can turn no one away. Meanwhile, the number of uninsured patients continues to rise, increasing 8 percent from 2007 to 2008. This makes it particularly dependent on outside funding streams and government subsidies.

Of the corporation's $6.7 billion budget, little comes from city tax dollars -- about $89 million. That too could be cut by $3.5 million, according to the mayor's executive budget proposal, threatening child health clinics.

Who to Turn To?

At a budget hearing on Wednesday, Councilmember Helen Sears sang the corporation's praises.

"How do you get through these state cuts and federal cuts?" the Queens legislator asked. "Your cuts get deeper and deeper and you manage to give quality care."

Some fear that will not happen for long.

As other nonprofit, private hospitals across the city close their doors, like Mary Immaculate Hospital and St. John's Queens Hospital, City Council members fear patients will inundate the corporation's facilities, further taxing the system.

"They are incredibly important part of the safety net in New York City and anything that is happening that is going to push them to reduce their ability to serve uninsured people in their outpatient departments is going to be devastating," said Elizabeth Swain, chief executive officer of the Community Health Care Association of New York.

As for the city, a Bloomberg administration spokesperson said in an e-mailed statement: "HHC faces fiscal challenges as most healthcare providers do and addressing these challenges will likely involve the corporation, the city, the state and the federal government -- at a time when needed reforms of the health care system are a national topic of much debate."

In 2004, Mayor Michael Bloomberg allocated $200 million to the city's public hospitals to help reverse year's of neglect by the Giuliani administration. It's unlikely they would do the same again with their own fiscal problems. Overall, both the administration and the council have little influence over the structural deficit the corporation faces.

Currently, the corporation is pressuring city officials to lobby state legislators for funding to stave off the budget gaps down the line. That will not halt their current restructuring, which, Aviles said, would most definitely result in a drop in services.

"It will require looking at the traditional approach that all hospitals can be all things to every community," said Aviles. "To some extent we may have to consolidate some of our services in some of our facilities so that we can maintain those essential services and access to those services, but deliver them as efficiently as possible."