State of Cycling

Even in packed subways, high gasoline costs and concerns about health, less than 1 percent of all New Yorkers regularly use their bicycles to commute to work. At the same time,18 percent of all New York City adults still smoke cigarettes.

Over the past five years, the Bloomberg administration has made a massive and somewhat successful effort to reduce the number of smokers. Now, can the same government that persuaded New Yorkers to stop smoking create an environment that will convince them to start cycling?

More than ten years ago, the Giuliani administration formally introduced the Bicycle Master Plan for New York City, an initiative to develop a city-wide bicycle network to increase ridership and integrate cycling into the city's transportation system. Since then, the plans have evolved. This spring, cycling has emerged as part of PlaNYC 2030, Mayor Michael Bloomberg's ambitious proposal to make New York City more environmentally friendly and reduce carbon emissions believed to cause global warming. The current plan calls for the completion of an 1,800-mile system of bike routes by 2030, as well as improvements to biking facilities and increasing public awareness. But New York still lags behind many other cities when it comes to promoting bicycling, and a number of questions remain about safety, facilities and the fight for always scarce space in the crowded city.

Building The Network

Since Bloomberg announced PlaNYC in April, the city has already begun work on trying to increase bicycling. Some advocates viewed earlier city efforts as sluggish. The city's previous transportation commissioner, Iris Weinshall, was criticized for being uninterested in cycling, and the department's bicycle program director resigned last summer. But advocates have praised Weinshall's successor, Janette Sadik-Khan, who was named commissioner in April, for her commitment to alternative transportation and environmental sustainability.

The administration is already trying to reach the cycling program’s first benchmark -- adding 200 miles of bike lanes by 2009. Overall, PlaNYC calls for:

• 500 miles of separated bike paths

• About 1,300 of miles of striped or marked bicycle lanes

• Additional greenways, or car-free paths that connect the city’s parks.

• Improving public education on cycling and safety issues and observation of traffic laws

• Installing 1,200 additional bike racks by 2009

The city’s move toward a complete bicycle network has not been without debate. A proposed bicycle lane on a car-free block of East 91st Street has drawn opposition from members of the local community who want to preserve the tranquility and safety of the street. The Upper East Side residents of Community Board 8 are also frustrated that city officials did not consult them before deciding on the lanes, according to David Liston, the board's chairman. "On something so serious, so important, and recognizing how important bike lanes are for the city, I don't know why they did not come to us sooner," he said. The community supports the city's efforts to install new lanes and encourage cycling, according to Liston, but he added, East 91st was "simply the worst location" for a bike path.

According to the New York Sun, residents of the Upper East Side have enlisted their elected officials all the way up to their congresswoman. The transportation department is considering an alternate route.

A plan to have bike lanes along Ninth Street in the Park Slope section of Brooklyn encountered opposition from residents hostile to bicyclists and from those who said the lanes would make it more difficult for them to double park in front of their homes to drop someone off. The city approved the lanes anyway.

Noah Budnick, deputy director of Transportation Alternatives, said the community tension over facilities for bicycling stems from New York’s longstanding focus on cars at the expense of cyclists and pedestrians. “Our city for the past six or seven decades has been designed around cars, which is the most inefficient use of city space to move people around,” he said. “What we’re left with is that bikers and walkers are fighting over the scraps.”_

Bike Sharing

Many New Yorkers cannot take advantage of the city’s lanes and paths because they either do not have a bike – it can be hard to store them in tiny apartments—or find it difficult to transport their bikes around the city. To address that issue, some cities around the world have implemented bike sharing. Advocates want New York to follow their lead.

" I think a look to a city like Paris would really be instructive," said David Haskell, founder of the New York Bike Share Project, referring to the French capital's recent launch of its own bike-share program. Paris currently provides more than 10,000 bikes that can be picked up, ridden and dropped off at another station in the city. Renters swipe a pre-paid subscription card and pay for any time beyond the first 30 minutes. And the city plans to install 10,000 more bikes within a year.

The Paris initiative, the largest in the world, is one of several around Europe that Haskell looks to when envisioning one for New York City. Last month he organized a five-day project in which riders could rent a bike for a free 30 minutes in SoHo and drop it off at another location. The program drew hundreds of people eager to try it out.

Since then, support has continued through e-mails and calls to his office, he said, and he hopes to launch an expanded follow-up project next spring. That program will be temporary, but Haskell called it “a way to keep the public interested,” while the city ultimately considers a permanent system.

Advocates are excited about the idea, and city officials considering whether it could work here. A bike-share program would require hundreds of stations at which to pick up and return the rented cycles. The department would not speculate on what else those stations might include. “Finding the space for all those stations is really something that’s under consideration,” said Joshua Benson, the Department of Transportation's bicycling program coordinator.

A Cycling Infrastructure

A system of shared bikes, though, is just one element in creating an entire infrastructure for cycling in New York. “We’re just seeing what’s out there in other cities,” Benson said. He said a “complete bike network" would include increased bicycle lanes, as well as bike parking and storage.

Budnick of Transportation Alternatives also emphasized the need for bicycle parking and storage -- the lack of safe storage is the number one reason why people in the city don’t take their bikes to work, according to 1999 report by the Department of City Planning. To that end, the transportation department under PlaNYC is continuing its CITYRACKS program -- in which the department builds racks based on requests from throughout the city -- and aims to put up 1,200 more racks in the next two years. The plan also calls for a law that would require commercial buildings to provide bicycle storage.

Budnick of Transportation Alternatives also emphasized the need for bicycle parking and storage -- the lack of safe storage is the number one reason why people in the city don’t take their bikes to work, according to 1999 report by the Department of City Planning. To that end, the transportation department under PlaNYC is continuing its CITYRACKS program -- in which the department builds racks based on requests from throughout the city -- and aims to put up 1,200 more racks in the next two years. The plan also calls for a law that would require commercial buildings to provide bicycle storage.

Safety

One challenge to increasing bicycle rider ship in the city is making it safer. A 2006 city study found that from 1996 to 2005, 225 cyclists died in crashes, 92 percent of them in accidents involving cars. Also, several high profile deaths in the past year, two from car crashes on a popular Hudson River bike path, have further highlighted the need to protect cyclists. One motorist, who killed a cyclist, drove along the bike lane, apparently not realizing it was not intended for motor traffic. Flexible plastic pylons are all that separate the Hudson River from motor traffic, prompting transportation officials to consider a switch to bollards, or steel posts or other barriers that are cemented to the ground.

A study released by Transportation Alternatives earlier this month found that 52 percent of cyclists surveyed felt “very safe” or “safe” in buffered lanes, in which there is an additional five-foot-wide painted space between the bike lane and auto traffic. Meanwhile, the study found, only 21 percent felt secure in conventional bike lanes, which offer no barriers between cyclists and drivers.

The study concluded that the city should come up with “more innovative ways” to protect bicyclists from car traffic as it adds bike lanes to major routes. “I think the next step in making the city’s bike network stronger is the city putting in actual protected bike lanes on the street,” Budnick said. He suggested that bollards be used to physically separate bike lanes from motor traffic.

The transportation department has recently begun to paint some bicycle lanes throughout the city bright green in order to make them more visible to car and truck drivers. Although many residents find the color ugly, the city plans to paint about five miles of these lanes in areas where drivers are more likely to clash with cyclists.

The city’s other current safety efforts include a free helmet giveaway and a recent law to protect bicycle delivery workers. Benson, the city’s bicycle program coordinator, also said an ad campaign would be launched in September that would “highlight the rights and responsibilities of motorists and cyclists.”

Haskell said the city deserves a lot of credit for its work with bicycles in the last two years. “There’s definitely been a shift in the understanding of how bikes can conquer the larger transportation challenges in the city,” he said. But, Haskell added, the administration still has work to do. “I would still urge the city to be a bit more bold with their thinking and a bit more visionary in terms of the scale of what might be done,” he said.Â

A Divided Council Confronts Congestion Pricing

In the touch and go, back and forth, here and there negotiations over Mayor Michael Bloomberg's congestion pricing plan, a new player got caught up in the controversy: the City Council.

If the mayor receives enough federal funding to move his plan forward and if it then receives the blessing of a 17-member commission, 51 council members will have to decide where they stand on charging cars $8 and trucks $21 to drive into or out of Manhattan below 86th Street during the workday.

Most council members are not yet ready to make that decision. But over the next several months, they could face a divisive issue, featuring the kind of democratic and sharp debate not really seen in council since the 2005 controversy over the city's waste management plan.

The Breakdown

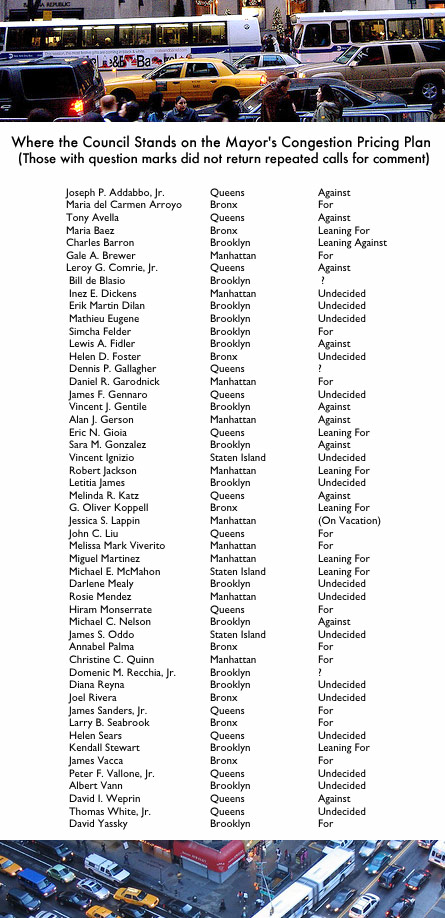

Of the 47 City Council members who responded to Gotham Gazette’s query, only 23 council members took definite positions on the mayor's proposal. The others are leaning one way or the other or say they are undecided.

Twenty council members support or lean toward the plan. Another 11 oppose it or lean against it. Nearly a third of the council, or 16 members, contacted by Gotham Gazette said they were undecided, and three others did not return repeated phone calls. Jessica Lappin was on vacation and so unavailable.

For the plan to pass, 26 council members would have to approve it. With City Council Speaker Christine Quinn supporting the fees, Bloomberg may be able to move some members over to his side.

The next step for congestion pricing could come as early as this week when the federal government tells the city whether it will receive up to $500 million to purchase equipment to implement congestion pricing and for mass transit improvements, including buses. The plan must then receive a favorable review from a 17-member commission charged with coming up with a plan to reduce the city’s notorious traffic jams, according to the bill approved by the state legislature late last month. If all that happens, then it will be the council’s turn to weigh in. If they approve congestion pricing, the final say will rest with the legislature and the governor.

Who Stands Where on Congestion Pricing

Surprisingly, where the council members’ districts are seem to have little effect on their position. One could assume those from the outer boroughs would be the most likely to oppose the idea. But some of congestion pricing's most outspoken supporters, like Councilmember John Liu, hail from Queens, while others who have expressed doubts, like Councilmember Alan Gerson of lower Manhattan, are from districts that supposedly would reap the most benefits from it.

Many of the council members listed as for or leaning for said their continued support hinged on the city making improvements in mass transit. Bloomberg has promised to do that, using first the federal funds and then the revenues from congestion pricing.

Council Gets Its Say

Congestion pricing has the potential to be that rare thing in City Hall – a divisive issue that could split alliances. As he has repeatedly done, the mayor initially wanted to exclude the City Council from having any role in congestion pricing. But during negotiations over the plan in Albany, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver reportedly insisted that the compromise creating the commission require the council's approval before the legislature could vote on any plan to relieve congestion.

"I've been insisting that the council has an absolute right to weigh in on this," said Councilmember Lewis Fidler – a congestion-pricing foe who introduced a resolution several months ago against the proposal. "Institutionally it's very important for the council that that be done. This is the issue of whether or not tolls are going to be imposed on the streets of New York," not Albany, he added. "I for one feel relieved."

Although the deadline for council to approve or reject the plan put forth by the commission is not until March 31, 2008, Council Speaker Christine Quinn is already gearing up to reach a consensus. Quinn, who will appoint three representatives for the 17-member commission, supports congestion pricing, albeit with conditions.

In a memo sent to council members last week, the speaker stated she would schedule individual meetings with every member to review their complaints, concerns and apprehensions regarding congestion pricing.

The memo states: "While I support congestion pricing, I am keenly aware that many of you have expressed concern about congestion pricing and will have questions about the agreement. I understand that a plan of this magnitude, whether congestion pricing or another method, will profoundly and uniquely affect each of your districts. I am committed to working with each and every one of you to hear and address those issues."

Their Reasons For Support

Council members, like other New Yorkers, recognize traffic is more than an inconvenience here – it creates health problems and affects the city economy. According to the mayor's proposal, congestion costs the city $13 billion in lost business revenue, lost time and increased vehicle costs. With congestion pricing, the report contends, 94,000 commuters would shift from driving to mass transit. A transition of that magnitude would consequently reduce the emissions that cause global warming and better the city's environment.

Council members, like other New Yorkers, recognize traffic is more than an inconvenience here – it creates health problems and affects the city economy. According to the mayor's proposal, congestion costs the city $13 billion in lost business revenue, lost time and increased vehicle costs. With congestion pricing, the report contends, 94,000 commuters would shift from driving to mass transit. A transition of that magnitude would consequently reduce the emissions that cause global warming and better the city's environment.

"Besides alleviating a lot of the pollution that goes into our environment from so many people that drive into work, it will help us improve our transportation system," said Councilmember Annabel Palma, a supporter of the mayor's plan dependent upon certain transportation improvements in her Bronx district. "And again it always helps to be able to put together a plan that will keep people healthier for longer periods of time."

While some council members said congestion pricing unfairly burdens those outside of Manhattan, others see the plan as righting a longstanding inequality from borough to borough. "I lean toward it from the fact it spreads out the burden Staten Islanders have borne," said Councilmember Michael McMahon, referring to the tolls his constituents pay. Under the plan, the tolls will count toward the $8 congestion fee.

Their Reasons For Concerns

Most council members' who oppose or lean against congestion pricing say they worry that the tolls will be implemented without the transportation improvements promised in Bloomberg's PlaNYC 2030 environmental proposal. These include five bus rapid transit routes in each borough, allowing buses to travel in special designated lanes, and increased capacity on the city's most traveled subway lines. Even those who have endorsed the mayor's pricing proposal, like council members Simcha Felder, Palma and Quinn, have said their support depends on these other promised improvements.

"I don’t believe we've exhausted every alternative before charging residents to drive into the city," said Queens Councilmember Joseph Addabbo, an outspoken critic of congestion pricing. "We could enforce cars (to stay out of) bus lanes. We could enforce other traffic rules. We could look at delivery hours."

A short list of other complaints include:

--fears that outer-borough neighborhoods would become parking lots for commuters wanting to leave their cars outside the congestion zone;

--concerns that congestion will increase outside the zone. This would raise emissions in some neighborhoods and increase health problems, like asthma, there;

--a belief that the $8 toll equates to a regressive, commuter tax that is unfair to the poor.

"I think the plan is myopic and shortsighted and does not show the real depth and purpose in creating the types of resolutions that would benefit the entire city of New York," said Councilmember Leroy Comrie.

The Undecided

The many council members who have not made up their minds raise an array of issues including whether commuters will use parking places, crowding out neighborhood residents, and what effect hundreds of cameras photographing drivers going into, within or out of the zone could have on the privacy and security of New Yorkers.

"What about above 86th Street?" asked Councilmember Thomas White of Queens. "What about the other boroughs? On face value, I'm not satisfied."

Other members representing districts outside the zone, like Maria Baez and James Sanders, worry about plan's effect on the poor. Both suggested incorporating a tax rebate for those charged by congestion pricing.

The undecided are united on one thing: Their main concern remains getting their constituents to their destinations in the fastest, easiest and cheapest way possible.

"What I fear is mass transit won't be prepared for it," said Councilmember Joel Rivera, who also questions the impact of a looming fare increase by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Rivera, though, is still open to the concept. "As a person that drives into the city… it gets congested."

Some are simply holding off on pledging support or opposition because the final details have not been determined. "The proof is in the pudding, and the pudding isn't even in the oven," said Councilmember Robert Jackson.

In fact, the council might never get to vote on congestion pricing. The commission, comprised of members appointed by the mayor, City Council speaker, governor, State Senate majority leader, Assembly speaker and minority leaders of both houses, would meet over the next several months. The plan it recommends does not have to resemble the mayor's. Its only criteria would be to reduce congestion by as much as Bloomberg's proposal – 6.3 percent.

Whatever comes out of this, many officials expressed optimism that in several years New York City will be healthier, greener and less congested. "It's going to be definitely different," said Councilmember Gale Brewer, a pricing supporter, discussing the so-called inevitable revisions to Bloomberg's plan. "If there is real mass transit plans, if we really have a discussion about high quality mass transit that happens with the $500 million, then I think people would be interested."

Â

Compromising on Congestion and Campaign Cash

Just a few days ago, the world as viewed from the State Capitol and City Hall, looked far different than it does today. Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver played his spoiler role as Mayor Michael Bloomberg, fresh from Sun Valley, Idaho, desperately tried to convince legislators to approve his plan to charge vehicles to enter or driver around Manhattan. Governor Eliot Spitzer smiled coldly from the cover of New York Magazine defending the anger that has become his hallmark - including his increasingly tawdry battle with Senator Majority Leader Joe Bruno. For his part, Bruno expressed little use for the Assembly or Spitzer

Just a few days ago, the world as viewed from the State Capitol and City Hall, looked far different than it does today. Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver played his spoiler role as Mayor Michael Bloomberg, fresh from Sun Valley, Idaho, desperately tried to convince legislators to approve his plan to charge vehicles to enter or driver around Manhattan. Governor Eliot Spitzer smiled coldly from the cover of New York Magazine defending the anger that has become his hallmark - including his increasingly tawdry battle with Senator Majority Leader Joe Bruno. For his part, Bruno expressed little use for the Assembly or Spitzer

Just another day in New York politics.

But following three days of plot turns that delighted bloggers up and down the Hudson, by Thursday evening everything had changed. The four men - individually -- announced deals on congestion pricing and campaign financing. A commission would try to hash out a plan to fight traffic congestion, and new limits would go into effect on contributions to candidates.

Still at the close of business last week, much remained murky, including when the legislature and governor would approve the deal, details of the agreements and the status of other outstanding issues, including legislative pay hikes, a key part of New York City's solid waste plan, expansion of the state's DNA database and more.

FOUR DAYS IN JULY

When legislators went home at the end of June, a number of issues remained unresolved. One, campaign finance reform, was a top priority of Spitzer's but Bruno stood in the way. Meanwhile, Bloomberg, with Bruno as an ally, was pressing his congestion pricing proposal. According to the mayor, the state needed to approve the plan by July 16 - last Monday - in order for the city to qualify for an estimated $500 million in federal transportation funds. But many members of the legislature objected to the driving fees and Silver seemed intent upon stymieing the plan. At the same time, Spitzer was blocking a pay hike for legislators, an increase in turn tied to raises for the state's judges.

Bloomberg wanted the legislature to go back into session on July 16 and hammer out its differences in time for the city to get the transportation aid from Washington. But the putative deadline for the federal funds came and went with no deal.

An irate Bloomberg fumed at Albany's inaction. For their part, the denizens of the capitol said that, unable or unwilling to deal with politics, the mayor had hurt his own cause. "When it came time to deal with people he didn't control, he didn't know how to do it," Assemblymember Richard Brodsky of Westchester, a key opponent of the congestion pricing plan, told the Times.

But talks continued. Finally on Thursday afternoon, Spitzer announced agreement on congestion pricing and campaign finance, along with two issues of less concern to New York City: a capital spending measure targeted largely at upstate and property tax relief for seniors. To the surprise of some, he did not mention salaries.

Four men in a room -- Spitzer, Silver, Bruno and, this time around, Bloomberg or more accurately, his representative Kevin Sheekey - had sat behind closed doors and hammered out a deal pundits called "The Big Ugly." In the horse-trading of politics, seemingly disparate issues became inextricably linked.

"Were this still a stand-alone issue, it would be dead right now," said Walter McCaffrey of Keep NYC Congestion Tax Free, an anti tax group, referring to the fee. "If anyone thinks this is not moving because of pay raises they are naive in the extreme."

At weeks' close, there was apparently no written official document detailing the agreements on congestion pricing or campaign finance reform. The leadership has not yet announced when members would assemble in Albany to vote on the deals hashed out secretly. Experienced observers expect announcements on other matters, particularly salaries, will be forthcoming but can't say what they will concern and when they will be announced.

With so much confusion, any or all of the agreements could still collapse. Capitol Confidential asked, "Will the deal hold long enough for lawmakers to come back? Will Bloomberg really get his traffic plan? And will New York find happiness in campaign finance reform?"

Stay tuned.

That said, here's the apparent status of the big issues at posting time.

CONGESTION PRICING

|

"We live in Staten Island, and we pay a lot of tolls. I know it works in other countries, but we seem to have so many more people. It would certainly be nice to get $500 million though." |

|

"I don't know much about it but it doesn't sound like a bad idea." |

|

"People should be allowed to drive into the city and I don't think they should be charging people more than what they already pay, especially since most people already can't afford to live in the city." |

|

"There are probably alternatives that can be resorted to before we do that, a last resort. I don't think we've tapped everything we need to tap. I know there are other cities that don't allow trucks and deliveries during certain hours, they make deliveries happen during the middle of the night. I frequently see congestion here because of trucks blocking the street." |

|

"You know, we're not on the highway, we're in the city. You're gonna charge people, what, $4.50? That's ridiculous. $8.00? No, he lost his mind. He could fix that manhole cover, that's 100 years old that blew up. That would be a good thing." |

|

"As someone who takes mass transit to work, I see first hand how badly the subway system could use the extra funds that congestion pricing would provide. As a cyclist, I'd be thrilled to see more cars taken off the road. And as someone who has a car, I think anyone who drives into the city during rush hour should be charged $8 for tying up traffic." |

|

"It's a necessary evil. Traffic is getting noticeably worse even within the 18 months I've owned a car. And it helps the environment, so why not? But I probably wouldn't drive into city if it gets implemented. I can't afford $8 a day." |

Last April, unveiling his PlaNYC 2030 for a more environmentally sustainable New York, Bloomberg proposed charging a fee for cars and truck entering or driving around much of Manhattan during peak hours. Known as congestion pricing and modeled on a program in effect in London since 2003, the plan was designed to reduce traffic and the pollution and congestion from it, generate fees to fund improvements in mass transit and qualify the city for a half a billion dollars in federal transportation aid.

Congestion pricing, and much of PlaNYC, won enthusiastic backing from an array of environmental, labor and business groups. But it also encountered staunch opposition from some politicians from Brooklyn and Queens and a number of state legislators. Given that the measure required approval from the state government that seemed likely to prove fatal.

The Deal

Faced with a shattering defeat that could have affected many parts of PlaNYC, Bloomberg late last week - three days after the deadline he had described as inviolate -- accepted the kind of deal he had once dismissed. Similar to a proposal previously made by Silver, the agreement sets up a commission to recommend a plan to reduce traffic congestion in New York City. Although a written proposal has not been released, Streetsblog and other sources report that it would:

--Establish a 17-member commission with three members each appointed by the mayor, the governor, the City Council speaker, the Senate majority leader and the Assembly speaker. The Senate minority leader and the Assembly minority leader would each get one appointee.

--After holding hearings and reviewing information, the commission will submit a plan to reduce traffic to the legislature, governor, mayor and City Council by January 31, 2008.

--The plan must be expected to reduce traffic by at least 6.3 percent.

--The City Council must first approve the plan. It would then require approval by the legislature and governor.

--All of this is contingent on the U.S. Department of Transportation providing at least $200 million.

Despite the many steps the city must go through before it can implement congestion pricing, Bloomberg remained impatient. "We will begin immediately to prepare for the installation of needed equipment to make our traffic plan a reality," he said.

Silver tried to put on the brakes. The mayor, the Assembly speaker told a press conference, is "prohibited from collecting a fee... He can put cameras on every street corner, but he can't use them to collect a fee."

Silver's cautions aside, advocacy groups had a generally upbeat reaction to last week's actions in Albany.

"Today is a watershed day for the health and the future of New York City," said a statement from Michael O'Loughlin, director of Campaign for New York's Future. In her official reaction, Marcia Bystryn, executive director of the New York League of Conservation Voters said, "We can all breathe a little bit easier today - and every day in the future - thanks to the leadership of Mayor Bloomberg, Assembly Speaker Silver, Majority Leader Bruno and Governor Spitzer."

While advocates recognize much work needs to be done, "six months ago no one would have said we would have gotten this far. We've made enormous strides," said Neysa Pranger, campaign coordinator of the Straphangers Campaign in an interview.

"Elected officials - the four men in that room - came to agreement that something needed to be done about traffic and air pollution and transit funding," said Noah Budnick, deputy director of Transportation Alternatives. "A course has been set for action. It has gone beyond talk."

The Looming Fight

The compromise changes the political equation by bringing the City Council into the picture - something Bloomberg had sought to avoid. While City Council Speaker Christine has endorsed the plan, her members seem largely divided. One count compiled by the Daily Politics lists 11 members other than Quinn as essentially in favor and nine as opposed or having major reservations. That leaves 30 members whose position is not known.

""I'm surprised that more council members aren't talking," said Queens Councilmember Tony Avella, who opposes the fees. "Even though it's the state legislature that will ultimately make the decision, the council should play a role."

Councilmember David Weprin who has opposed congestion pricing from day one, said he thinks most of his colleague agree with him.

But despite apparent opposition, City Councilmember John Liu, head of the transportation committee and a supporter, thinks many members will come around. Getting improvements in mass transit - particularly better express bus service for more distant parts of the outer boroughs - could go a long way toward persuading skeptical council members, he said. Now, Liu said, many New Yorkers have to "hop on a local bus for a half hour to get to the subways and then if they can even squeeze themselves in" have a 90-minute trip to work in Manhattan. If those riders could instead take a good, reliable express bus to their jobs, councilmembers, Liu thinks, would feel more comfortable "imposing that charge on people who still insist upon driving their own cars."

And even if the council can be won over, the legislature remains a barrier - and maybe not just the openly obstreperous Assembly. On Monday night, "congestion pricing could not muster enough votes in the Republican Senate. No one should forget that," McCaffrey said, adding that even some Senate Republicans, the groups thought to be most supportive of the idea, opposed it.

The Final Answer

So, what could emerge?

Supporters of congestion pricing think their plan will triumph.

Liu, in fact, thinks it may be all but inevitable. "I don't know how long we can stave it off in New York City," he said.

While congestion pricing has proved successful in London, many of the alternatives - restricting access to the city on certain days, for example - have not worked as well, according to Pranger.

And she thinks the logic of congestion pricing remain inescapable: It offers, she said, " the benefit of assisting those who can afford to get around the least which far outweigh charging drivers who are by and large wealthier."

But Hope Cohen, deputy director of the Center for Rethinking Development at the Manhattan Institute says alternate ideas could win more support and still meet federal guidelines for getting the transportation aid. Those requirements including some "tolling component" - not necessarily a congestion fee -- and using technology. (Cohen notes that under the federal rules, any plan must also promote telecommuting as a means to reduce car trips.) One possibility, which Cohen termed "the most American thing out there," would set aside special high occupancy vehicle lanes and charge people to use them.

The next several months will provide "the opportunity for this to be looked at in a more thorough fashion," said McCaffrey. He hopes that discussion will give rise to alternate solutions, such as stricter laws barring cars from "blocking the box" and removing tens of thousands of permit that allow city employees to park for free.

Whatever emerges, Pranger said, "After a three-month gap, people are finally talking about the details and what will work. That's a useful and good sign."

CAMPAIGN FINANCE

As much as Bloomberg wanted congestion pricing, Spitzer wanted campaign finance reform. He had been vowing to clean up Albany since before he became governor and campaign finance reform was an integral part of that drive.

Certainly many would argue that change was long overdue. It has been more than three decades since New York revised its campaign finance laws. The neighboring states of New Jersey and Connecticut have introduced some aspects of publicly financed campaigns and pay to play regulations. New York City far surpassed the state on campaign finance regulations years ago and instituted even more restrictions earlier this month. But the state lagged behind, setting few constraints on who could donate to political campaigns or how much they could contribute.

The accord last week came after a period of intense acrimony - including profanity-laced tirades and accusations of spying - between Spitzer and his campaign finance nemesis Bruno. The agreement delighted some good government groups, but they cautioned, the proposed changes are just a start. The changes do not go into effect until 2009 - the year after what could be a bloody - and expensive fight - between Democrats and Republicans for control of the State Senate.

Unwritten Legislation

Without a bill, it is difficult to analyze what the legislation, if and when it's passed and signed, would or would not allow. But in announcing the agreement on Thursday, the governor's office did reveal some details:

- Individuals will be limited to contributing $25,000 to a candidate for statewide office, down from the current ceiling of more than $50,000.

- For State Senate candidates, the contribution limits would be $11,500, down from $15,500.

- Maximum donation to an Assembly candidate would drop to $4,600 from $7,600.

These limits are far more lenient than those for federal or New York City elections. For example, the maximum amount an individual can give to a candidate for mayor is $4,950.

In addition, the new campaign finance system would:

-- Close the corporate subsidy loophole. Under current state finance laws, corporations can give only $5,000 annually to a campaign. But corporate subsidies are treated as separate entities, with each one able to contribute $5,000. Under the agreement, a corporation and its subsidiaries would be treated as one unit, allowed to contribute a total of $5,000.

--Bar contributions from lobbyists

--Prohibit contributions from so-called limited liability companies that were recently created or have few, if any, assets. This is aimed at special interests groups, which create dozens of pseudo-partnerships to avoid complying with limits on campaign contribution.

--Phase in caps on contributions to political parties' "housekeeping" accounts. These accounts are supposed to cover the parties' organizational activities but are often actually used to finance campaigns. A $300,000 annual cap would take effect in 2009, decreasing to $150,000 in 2013.

--Require individuals to list their occupation and employer when they make campaign contributions. Contributors would also have to disclose who, if anyone, is bundling, or collecting, money from multiple donors for one campaign.

A First Step?

The agreement does not include public financing of campaigns, and many other aspects of it remain vague. Reviewing this, good government groups and advocates said the new rules represent a step in the right direction, but do not go nearly far enough.

"The contributions were dramatically lowered, but by any point of comparison they are still dramatically high," said Suzanne Novak, the deputy director of the democracy program at the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law. "I think everybody including Governor Spitzer agrees that this is only a first step... There a nine million things in New York that needs to be corrected."

Some reforms initially on Spitzer's agenda appear to have been lost. One, said Novak, would have prohibited the "personal use" of campaign contributions. Currently use of these funds is largely unrestricted, letting legislators and candidates use their campaign funds on everything from flowers to lavish dinners at swanky restaurants. But putting control on this is anathema to some legislators in Albany, said those involved in the negotiations.

The compromise also sidesteps further limits on contributions from political action committees. New York has the highest cap in the nation for contributions from these committees in a governor's race -- more than $50,000 per election cycle, according to the Brennan Center.

Overall, advocates see the agreement as weaker than what the governor initially wanted. "The proposal that started off from the governor was a strong proposal, because it addressed each of the areas that need improvement in the state campaign finance laws," said Russ Haven of the New York Public Interest Research Group. "In the beginning they were very significant, but they weren't radical overhauls. In the natural progress, there were some areas that either fell off the table or got weakened."

Some political professionals do not expect the reforms to change much. "It's going to mean that fundraisers are going to have to be more inventive to get big bucks, but they will," said Norman Adler, president of lobbying firm Bolton-St. Johns. "It's like water in a basement. No matter what you do it always creeps in."

For their part, good government forces hope to see a second phase of campaign finance reform that would include the public financing of campaigns. But considering state leaders have not even approved this first phase - and Spitzer has expressed readiness to move onto other issues - a second part could be unlikely anytime soon.

AWAITING ACTION

The legislators left a number of other issues unresolved when they ended their regular legislative session. These are some pieces of unfinished business of particular interest to the city:

Gansevoort Recycling Station: Bloomberg's solid waste plan for the city calls for construction of a recycling station on Gansevoort peninsula in the Hudson River. Because the land is in Hudson River Park, the city needs state approval to build the station there. The Senate has said yes, but the issue stalled in the Assembly, where several Manhattan members have moved to block construction. The station, city officials said, is vital to its overall waste management plan.

Tax Credits for Housing: The legislature has approved a version of 421a, a city program that provides tax breaks to housing developers in an effort to encourage construction of affordable housing. The mayor and City Council had proposed their own version late last year. But the version approved by the legislature - and apparently authored by Assemblymember Vito Lopez of Brooklyn -- included a huge tax break for Bruce Ratner's controversial Atlantic Yards project. And according to the city housing agency, the legislature's bill places additional conditions on developers that would hamper the city's effort to promote building of middle class housing. Bloomberg and Quinn have both urged Spitzer to veto it.

DNA Data Bank: Spitzer would like to expand the collection of DNA to individuals found guilty of felonies or misdemeanors, in state prison or on parole or probation. The measure has been stalled in past years in the Assembly.

Wicks Law: The legislature planned to overhaul the Wicks Law -which requires multiple construction contracts for projects over $50,000. The law allegedly increases construction costs by 20 percent. A measure has passed the Assembly, but not the Senate.

Brownfields: Spitzer introduced legislation in early June to overhaul how the state would distribute tax credits to businesses and nonprofits that clean up, restore and development contaminated brownfield sites. The legislation stalled amid disputes between Spitzer and Bruno.

Â

Dorothy Coven

Dorothy Coven  Abu

Abu Dana

Dana Dan Milstein

Dan Milstein Tina

Tina Bill Yates

Bill Yates Rodney Tan

Rodney Tan