The Transportation Bond Act: Vote No

Gotham is an old city with an aging physical infrastructure. But the state’s $2.9 billion Transportation Bond Act, which will be on the November 8 ballot as “Proposal No. 2,” is not the best way for New York City to get the money it needs for its vital transportation assets.

The city certainly does need money for its mass transit, roads and bridges. New York’s subway system, parts of which turned 100 years old last year, needs $18 billion in investment over the next four years just to maintain its current state of repair. More than half of the city’s bridges are considered to be in less-than-stellar condition, and some are actively deteriorating.

But the transportation bonds on the ballot, if approved, will be issued by the state, not the city. The state doesn’t have infinite funds, and thus should make each dollar go a long way. But, despite this, it has not prioritized its proposed transportation-infrastructure investments according to urgent need.

THE CITY’S SHARE

What does this mean for New York City?

The city’s subways, roads and bridges will receive about $1.6 billion of the bond proceeds. At 55 percent of the total, this doesn’t sound like such a bad deal – especially in light of the fact that city residents, workers and businesses pay a little less than half of state taxes.

But the problem is that of that $1.6 billion earmarked for New York City, the bonds provide only about $700 million in funding for projects that the city needs completed now. So, in effect, New York City taxpayers will pay about $1.3 billion (their share of state taxes to fund the bond issue) in order to get back about half that in investment so critically necessary that it justifies new debt.

To wit: The bond act would provide the state-run Metropolitan Transportation Authority with $450 million to maintain the MTA’s core infrastructure, much of it within New York City. This means hundreds of millions of dollars for such mundane but crucial investments as new subway cars and buses, track replacement, tunnel lighting and other maintenance.

BIG TICKET ITEMS

But the bond act would provide a further billion dollars for several pie-in-the-sky expansion projects at the MTA: $450 million each for the Second Avenue subway (from the Bronx to Lower Manhattan) and for the East Side Access project (to connect Long Island Rail Road commuters to the East Side of Manhattan), and $100 million for a rail link from Lower Manhattan to Kennedy Airport.

Any one of these expansion projects might be worth seeing through to completion – but neither the city nor the state has committed to doing that. The Second Avenue subway, for example, will cost $16 billion.

In a rational world, the city and state would pick one of these projects – and make room in the budget to raise the capital necessary to build it. But each Albany official has his pet New York City project (Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver likes the Second Avenue Subway, while Governor Pataki likes the rail link to JFK), so no single project ever gets enough funds to make real progress.

Until the state and the city can figure out which of these three multibillion-dollar projects it likes best, the MTA would do better to commit the entire $1.45 billion raised through the transportation bond act to making critical investments in the assets it already has, to ensure that New Yorkers can depend on a reliable transportation system.

IMPROVING ROADS

What about roads? Of $1.45 billion earmarked for roads and bridges statewide, the city will get $273 million, or 19 percent. Some of the projects involve work on critical arteries in and out of the city: $81 million to rehabilitate the Van Wyck Expressway in Queens and $23 million to make repairs to the Henry Hudson Parkway between Manhattan and the Bronx. But at least one major project is not quite so critical: $19 million for a “green oasis” in the Bronx.

And to get its $273 million, the city must help pay for $1.2 billion road projects outside the city, including $21.5 million for 11 miles of new hiking trails in Washington County and a new pedestrian bridge near the Erie Canal.

CONTROLLING STATE SPENDING

These initiatives, and dozens of relatively small upstate road projects, may indeed be worthy – and no one is suggesting that upstate be deprived of infrastructure critical to its economy, or that the congested Bronx be deprived of green space.

But the state has so badly mismanaged its finances in recent years that it already has far too much long-term debt: more than $48 billion, which puts it fifth in the nation in terms of debt per person. According to state Comptroller Alan Hevesi, only about half of that debt was for prudent investment in long-term capital assets like transportation infrastructure – another 20 percent was for day-to-day operations, and another 25 percent was to fund state and local programs that should be paid for upfront.

Thus, it is not prudent for the state to raise new debt for worthy “extras.” Every penny should go toward the critical infrastructure that is badly in need of maintenance and repair.

Hiking trails and greenways are great – but the taxpayers who want them should pressure their local politicians to pressure Albany to get the state budget under control, so that we can afford to help pay for them without breaking the bank. If Albany were to cut its bloated and fraudulent Medicaid program by 15 percent, for example, state and local governments would have an extra $3 billion each year to fund smaller capital projects upfront.

Until then, city taxpayers would do better to vote down the Transportation Bond Act, and Gotham would do better to raise $700 million in debt on its own to pay for critical investments in its roads, and to help the MTA pay for critical investments in the subway.

This would send Albany a message: No more debt until state leaders reform the budget to get the debt we have under control.

Nicole Gelinas, a chartered financial analyst, is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a contributing editor to City Journal magazine.

• • • • • • •

• The Transportation Bond Act: Vote Yes by Jeremy Soffin

• • • • • • •

For more information against the Transportation Bond Act:

• CBC Announces Opposition To Transportation Bond Act (in .PDF format)

A statement from the Citizens Budget Commission

• New York's Endangered Future: Debt Beyond Our Means (in .PDF format)

A report on state borrowing by the Citizens Budget Commission

• Vote No

A position paper by the Conservative Party of New York

• Staten Island Borough President Opposes Transportation Bond Act

• No on Prop 2

A New York Post editorial Â

Transportation Bond Act

With mayoral candidates giving little attention to transportation issues, voters' biggest choice in the transportation arena will be their vote on the 2005 Transportation Bond Act. The bond act, approved by the Legislature this spring as part of a 5-year, $36 billion capital plan, would authorize $2.9 billion in state-backed borrowing for transportation, to be repaid through general revenues. One-half of the bond act funds would be dedicated to public transportation in New York City and its suburbs. Projects to be funded include:

• $450 million to move ahead with the Second Avenue Subway

• $450 million for the East Side Access project, connecting the Long Island Rail Road to Grand Central Terminal;

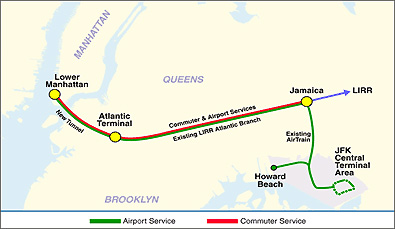

• $100 million for a rail link between lower Manhattan and Kennedy airport;

• $115 million for purchase of new subway and commuter railroad cars;

• $90 million for new buses; and

• $161 million for track replacement and tunnel lighting. An additional $235 million is set aside for upstate public transportation systems.

Although many people think of New York City as synonymous with transit and upstate as synonymous with highway spending, in fact, a substantial amount of statewide highway spending goes to New York City projects. Twenty-three percent of the bond's highway funding will be spent in the city. New York City highway projects (In PDF Format) include:

• $81 million for Kew Gardens Interchange/Van Wyck Expressway Improvements;

• $30 million for closed circuit television cameras, electronic message signs, vehicle detection devices and highway advisory radio on the FDR Drive and Henry Hudson Parkway;

• $23 million for Henry Hudson Parkway Rehabilitation;

• $25 million for West Shore Expressway Access and Safety Improvements;

• $19 million for the Bronx River Greenway; and

• $11 million for Long Island Railroad Bridge Upgrades to allow heavier, larger rail cars to access the Brooklyn, Queens and Long Island market areas.

Bond act spending also aims to maintain the percentage of state highway bridges in New York City that are rated as in good or excellent condition and slightly improve the proportion of interstate highway lane mileage in New York City that is rated as in good or excellent condition.

No one seriously disputes the importance of maintaining and upgrading the state's transportation system. The Bond Act has thus attracted a long list of supporters including Governor George Pataki, Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, State Comptroller Alan Hevesi, and transit advocacy, environmental and civic groups, including the NYPIRG Straphangers Campaign and the New York Public Transit Association. Both Mayor Michael Bloomberg and his opponent, Fernando Ferrer, support the bond act.

Supporters say that the Transportation Bond Act funds are vital to maintaining the state's sprawling and aging transportation infrastructure. The funding is also critical to construction of the Second Avenue Subway and East Side Access -- projects long discussed and planned but only now garnering the necessary funding. As much as $4 billion in federal funding is contingent on the bond act passing since the federal government evaluates projects on the level of local financial support. Supporters also point out that bond act spending will create construction jobs in the short term and spur economic growth for years to come.

The bond act has also attracted opposition, primarily from groups that feel the state already has too much debt. The Citizens Budget Commission (In PDF Format) says that the state is poised to take on $19 billion in new debt in the next five years. Only the $2.9 billion in the bond act requires voter approval, however. The budget commission argues that voters should reject the bond act as the only way to say no to the overall growth in borrowing.

The Automobile Club of New York also urges voters to reject the Transportation Bond Act. The Auto Club criticizes the state for raiding the highway trust fund, whose revenues come from the gas tax and auto registration fees. The Auto Club says that the state has used trust fund revenues to plug general budget shortfalls. The Auto Club argues that instead of borrowing to pay for transportation improvements, the integrity of the trust fund should be maintained and used for these projects.

Supporters reply that the real choice -- aside from underfunding transportation -- is between state-backed borrowing and borrowing that would be paid back through transit fares. They point out that after the 2000 Bond Act failed, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority borrowed heavily, leading to two fare increases since then.

In 2000, a $3.8 billion Transportation Bond Act narrowly failed to win voter approval. Prospects for this year's proposal are uncertain. A recent Quinnipiac University poll found voters statewide supporting the measure by a 56 percent to 36 percent margin. New York City voters supported it by 67 to 26 percent and suburban voters by 60 to 32 percent. Upstate voters were about evenly split.

While encouraging to supporters, these poll numbers also provide reason for caution because polls before the 2000 election also showed a majority in support. On election day, many New York City voters "who would be expected to vote favorably" overlooked the proposition in the lower right corner of the ballot. In fact, had the dropoff from the presidential vote to the bond act vote been the same downstate as upstate in 2000, the measure would have passed.

Supporters are aiming to heed the lessons of 2000. A group of business and building associations has funded a statewide Vote Yes for Transportation campaign. The $1.5 million campaign will include door to door canvassing and upstate radio ads.

Supporters have also moved to shore up support on Staten Island. The MTA recently shifted funds to build a third MTA bus depot on the island after the borough president, James Molinaro, criticized the measure.

Chances for passage of the 2005 Bond Act appear to be better than the 2000 measure, which failed narrowly, but are not assured. Voters thus have an important and very real choice to make on November 8.

Bruce Schaller, who has been in charge of the transportation topic page since its inception in 1999, is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Bruce Schaller, who has been in charge of the transportation topic page since its inception in 1999, is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Mayoral Issue Grid: Transportation

TRANSPORTATION

-2nd Ave Subway

-7 Extension

-Rail Link from Lower Manhattan to JFK Airport

-Rail Freight tunnel

-East River Tolls

-Congestion Pricing

-Subway Commute?

The last new subway line opened in New York City nearly 65 years ago, but candidates for mayor are making bold promises to undertake new mass transit plans.

For years, officials have been promising a Second Avenue Subway. It was first proposed in the 1920s. Recently, the MTA committed $1 billion for the subway line that would run from 125th Street to Hanover Square. It will cost an estimated $12.5 billion and take 17 years to build.

As part of his plan to develop the West Side of Manhattan, Mayor Michael Bloomerg has also proposed an extension of the number 7-subway line to 11th Avenue. It will cost an estimated $2 billion.

In Lower Manhattan, officials have plans to build a direct rail link from downtown to John F. Kennedy airport.

Some officials are also calling for a cross-harbor rail tunnel to be built between New Jersey and Brooklyn. The 5.5-mile tunnel would ship goods into the city and reduce truck traffic on area roads. As part of a new federal transportation funding bill, U.S. Rep. Jerrold Nadler secured $100 million to help launch the project.

While there are tolls on many bridges and tunnels in New York City, there are 12 city-owned bridges between Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx that are free to cross. Some estimate that charging $7 to cross the East River bridges and $3 for the Harlem River bridges could generate as much as $690 million a year.

Another way to reduce traffic and pollution is called "congestion pricing," charging drivers varying prices to come into the city at certain times of day. The city of London has instituted congestion pricing, charging people higher fees for driving in and out of the city at rush hour. The practice has reduced traffic in the city by 30 percent.

When running for office in 2001, Michael Bloomberg committed to ride the subway to City Hall to demonstrate his commitment to the environment and to public transportation.

Fernando Ferrer supports the construction of the Second Avenue subway and the 7-train extension to the West Side of Manhattan.

He is also a supporter of the cross-harbor freight tunnel between New Jersey and Brooklyn.

Ferrer is opposed to tolls on the East River bridges. At a recent forum he said, "Tolls on the East River bridges, even Mike Bloomberg walked away from that because he knows one other thing: There are people in this city who work hard every day who depend on their vehicles to make deliveries or get in to work. We've got to find a way to get them to use mass transit. But I'm not going to be the one to say they can't earn a living in New York City."

However, Ferrer does support congestion pricing. In a questionnaire for the New York League of Conservation voters, he wrote; "I do favor a congestion pricing policy, but one that is part of a larger framework; a framework which incorporates an expanded freight rail system, an efficient subway system, and an expanded ferry system."

At a recent forum, Ferrer said, if elected, he would take the subway from Gracie Mansion to City Hall.

Michael Bloomberg has expressed general support of the Second Avenue subway line, but has spent considerable effort on the plan to extend the 7-train, because it was part of his plan for a West Side stadium.

Bloomberg supports a lower Manhattan rail link to JFK, which he called “the single most important project for the future of Lower Manhattan” in his 2005 State of the City address

In March, Mayor Bloomberg withdrew city support for the cross-harbor rail freight tunnel between New Jersey and Brooklyn. Some residents of Brooklyn are opposed to the project because they say it will bring more traffic and pollution to their neighborhood. Bloomberg says he now agrees with them.

Bloomberg proposed tolling the East River bridges to help raise money during the fiscal crisis, but he dropped the idea.

Bloomberg is open to the idea of congestion pricing. In a questionnaire for the League of Conservation Voters, Bloomberg wrote; "To determine the feasibility and effectiveness of implementing a congestion pricing program, the administration is closely studying the impact of London's program on that city's traffic congestion, as well as any corollary effects of the policy. While London's program has reduced traffic congestion dramatically in the business district, according to reports by the London Chamber of Commerce and the Royal Institute for Chartered Surveyors, there has been a significant decrease in business activity in the area since the policy was introduced. The program's high operating costs have also limited the city's net revenue. We will continue to study the issue, but will not implement such a policy that could have a deleterious effect on local businesses."

Mayor Bloomberg regularly takes the subway from his house on the Upper East Side to City Hall.

RELATED ARTICLES:

- Security and the NYC Subways

- The State Budget’s $38.5 Billion Transportation Program

- What's Better, What's Worse During Bloomberg's Administration?

- Rail Freight Tunnel

- New Subway Projects and Their Benefits

- The Proposed Trains to Planes

Â