Looking for Government Help on Housing

The prospects for resolving New York City’s affordable housing crisis have suddenly brightened thanks to the recent election results. Housing advocates are excited that a Democratic Congress and Senate can address a long list of problems contributing to the crisis, a list that includes the loss of federally subsidized housing in Section 8 projects and the financial difficulties faced by the New York City Housing Authority.

“The election results are absolutely thrilling for those of us working on housing issues and the tenant movement,” said Patrick Coleman of Tenants and Neighbors, the statewide tenant lobby group.

Victor Bach, senior housing policy expert at Community Service Society, agreed.

“I think it’s a big opportunity,” Bach said. “It certainly changes what we expect in terms of housing initiatives coming from Washington.”

In Washington, the Democrats can now move forward with long-stalled plans for a national low-income housing trust fund and seek to repeal laws passed in 1998 that require some residents of public housing to do community service or face eviction, Bach said.

Democrats like Representative Barney Frank of Massachusetts, who has long pushed for government intervention in housing, and New York Representative Charles Rangel will be able to use their new clout to address the financing of affordable housing and other federal housing policies. Frank is expected to become chair of the Financial Services Committee and Rangel chair of the Ways and Means Committee.

Coleman of Tenants and Neighbors recalled attending rallies where Frank's commitment to affordable housing was clear. "He has the background as a community activist and he is very knowledgeable about Section 8" and other housing issues, Coleman said.

The federal government has done very little to preserve and create affordable housing for years, according to advocates. They now hope that will change with the Democratic gains.

“We need allies in Congress (to work on housing issues) and now we’ve got that,” Coleman said. The federal department of Housing and Urban Development, he said, “has only listened to the Republicans for the last six years. It’s been a nightmare. Now HUD is going to have to respond to Democrats who will be in positions to oversee HUD.”

On the state level, housing advocates hope to counter 12 years of inaction on housing by outgoing Governor George Pataki. (A report from the Pratt Institute for Community Development released in June described in detail how little Pataki has done to create and preserve affordable housing, especially compared to his predecessors.)

Advocates look to Governor-elect Eliot Spitzer to reinvigorate the state’s efforts, but many are unsure what to expect. Spitzer comes from a real estate family, they note, and the real estate lobby is always powerful. Nevertheless, advocates hope Spitzer strengthens rent regulation laws and overhauls the agency charged with enforcing those laws, the Division of Housing and Community Renewal. Spitzer has already indicated he supports the use of administrative tribunals to address repair issues, one item on advocates’ agenda, but does not support repeal of the Urstadt Law, which restricts City Council’s ability to write rent regulation laws that are stricter than state laws.

Again, advocates are looking to Spitzer to put more resources into preserving and creating affordable housing.

“Spitzer has said some good words about preservation of Mitchell-Lama and other subsidized housing,” Bach said. The governor could also “restore operating subsidies” to public housing that Pataki cut in 1998. The New York City Housing Authority has significant budget deficits and this summer announced plans to hike rents and fees for repairs to address that deficit.

Noting the new governor has also “said some good words about that,” Bach said, “We expect to hold him to his words.”

Joe Lamport is the assistant director of the City-Wide Task Force on Housing Court, a coalition of community housing organizations. Â

The Staten Island Ferry Crash Three Years Later

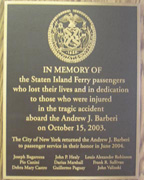

It is easy to miss the small plaque on the wall of the ferry honoring the people who died in a terrible accident on October 15, 2003. Repaired and back in service, the Andrew J. Barberi looks like the other eight Staten Island ferries, but it was the boat that failed to slide into its usual slip and instead crashed into a concrete pier. Eleven people died and 165 were injured. The captain on duty had been overmedicated and passed out as the boat charged full-speed into the pier.

Repaired and back in service, the Andrew J. Barberi looks like the other eight Staten Island ferries, but it was the boat that failed to slide into its usual slip and instead crashed into a concrete pier. Eleven people died and 165 were injured. The captain on duty had been overmedicated and passed out as the boat charged full-speed into the pier.

Three years later, while the ferry trudges dutifully back and forth on its 25-minute journey from Lower Manhattan to Staten Island, it remains a continuing and costly drama for those involved – including City Hall.

Crime And Punishment

The criminal cases have been settled. Federal prosecutors used an obscure 1838 maritime law known as seaman's manslaughter to charge both the pilot and the director of ferry operations. It is the same law that was used to prosecute executives when an excursion boat in the East River sank, killing more than 1,000 people. That happened in 1904, which was the last time a vessel in New York waters killed or maimed a large group of people – until the Andrew J. Barberi.

Richard Smith, the pilot who passed out at the helm that day, is incarcerated. Right after the accident, he had attempted suicide twice but failed. He pleaded guilty to 11 counts of seaman's manslaughter and making false statements. He is serving an 18-month sentence.

Richard Smith, the pilot who passed out at the helm that day, is incarcerated. Right after the accident, he had attempted suicide twice but failed. He pleaded guilty to 11 counts of seaman's manslaughter and making false statements. He is serving an 18-month sentence.

The ferryboat captain, Michael Gansas, was in the outbound wheelhouse doing paperwork during the crash. Prosecutors said that since the two-pilot rule was not enforced at the time of the crash, Gansas would not be charged with a crime. Since Gansas ducked investigators right after the accident, the city fired him. He sued the city for reinstatement but lost.

The director of ferry operations at that time was Patrick Ryan. He is in prison for not enforcing the rule requiring that two qualified pilots be in the wheelhouse at all times. He pleaded guilty to seaman's manslaughter and making a false statement to investigators and is serving a sentence of a year and a day at Allenwood Federal Correctional Complex.

Smith's physician, Dr. William Tursi, had hidden evidence of the pilot's medical problems and use of medication. He received probation, six months of home confinement and 300 hours of community service. His license to practice medicine was suspended.

The port captain, John Mauldin, who is Ryan's brother-in-law, received two years' probation for making false statements to investigators.

A crewmember, mate Robert Rush, was in the wheelhouse with the pilot, but didn't see the blackout. Officials suspended him from his job after he failed to show up for a meeting with investigators.

City Liability

Rulings are still pending on some of the issues that will affect how outstanding victims' claims will be settled. City attorneys have tried some odd arguments in court to limit liability. The accident involved an act of God because of the captain's medical condition. That would absolve City Hall of responsibility for some damages. The city government’s court filings also present seemingly contradictory blame of "intentional misconduct of Captain Smith…and the negligence of Mate Rush." That would mean that the crew was responsible, not the city (in the form of supervisors).In addition, attorneys argued that maritime law limits the amount of compensation to the cost of the vessel. That would be $14 million (though settlements already made have exceeded that amount).

Victims argued that ferry rules mandate two licensed pilots in the wheelhouse during docking. Federal prosecutors found two printed rulebooks—from 1908 and 1958—that list the two-pilot rule. If the rule was clearly on the books, the city may have to pay out much more to victims.

The city even paid for the (unsuccessful) defense of Patrick Ryan, the director of ferry operations, saying he was unfairly prosecuted for seaman's manslaughter. Criminal conviction of the ferry official (not just the personnel on board) could mean the city will be held responsible in civil suits by victims.

The city also paid for lawyers for 52 other city employees.

The city has settled 110 claims with $16 million so far with widely varying amounts. The largest settlement so far, $8.9 million, has gone to Paul Esposito, a waiter who lost both legs in the accident. William Castro, whose 39-year-old wife Debra died of injuries two months after the accident, received $3 million. One injured passenger got more than $1 million, and another received $500.

Another 81 victims' claims are pending. All the claims together total $3.2 billion.

Another lawsuit demands $8 million from the city for a tugboat that assisted the ferry. Immediately after the crash, the Dorothy J chugged over to the ferry, helped get the boat into the slip and held her steady for 68 hours. Maritime law allows the operator of such a vessel to claim compensation.

Other expenses for the city include nearly $7 million to repair the ferry and $1.4 million to repair the damaged pier. The city has also paid almost $4 million to outside attorneys.

Rules and Crews

Some 30 accidents caused by carelessness or lapses in judgment have marred the generally reliable service in recent years, according to an examination of records by the New York Times.

The most damaging accident before the Barberi crash happened in 1978, when a ferry rammed a seawall, injuring 200 people. In 1963, a ferry sank. While those and other accidents were serious, none caused fatalities. Many incidents could have been prevented with more vigilance by the crew, investigators found. But few procedures changed over the years.

Now, because of the deaths in the Barberi accident, rules for running the ferries have been firmed up and are more likely to be taken more seriously. In 2004, new regulations mandated more staffing on the boats, background checks, a strict drug and alcohol policy, more stringent medical exams for employees, surveillance cameras on board, better signs, and communication with fellow crewmembers.

There were always supposed to be two people capable of driving the boat in the wheelhouse. In practice, few ferry operators had ever followed the rule. Now the rules are more explicit. Three people are required, two of them pilots.

The ferry operation had been criticized for cronyism and nepotism. A change in management is meant to change that culture. Less than a year after the crash, James DeSimone, a graduate of the State University of New York Maritime College and a former vice president of a tugboat company and of New York Water Taxi, became the new chief operating officer.

There are questions about why the ferries are run by the city Department of Transportation and not by the state-run Metropolitan Transit Authority, as all the other city public transportation is. "We think it needs to be integrated into the public transportation system as a whole," Carter Craft of the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance told the Daily News.

Anachronistic Transportation

The city took over ferry service in 1905. It was—and still is—the only direct way to get from Staten Island to Manhattan. It seems like an anachronism in such a big city, to rely on boats to carry vast numbers of commuters. But only the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge provides a faster direct method of getting from Staten Island to other boroughs (specifically to Brooklyn). Two bridges carry vehicles to New Jersey. After 9/11, motorized vehicles could no longer travel on the ferry. The ferries remain an essential service for commuters.

The service runs 110 times a day, transporting 65,000 people. That adds up to some 19 million people a year. That would be a massive public transportation system in most cities. In New York, where people take 7.1 million subway and bus rides in the city every day, the ferry represents a small program.

Since 1997, the service has been free. It was too complicated to integrate into the new Metro Card system, said Mayor Rudolph Giuliani at the time.

Today, rebuilding and remodeling of the terminals at both ends have made the trip more pleasant. Renovations replaced the grubby terminals with shiny new structures more welcoming to commuters and tourists.

The Manhattan side features a glass-fronted building with a big blue neon Staten Island Ferry sign. Inside, but still visible from the street, the words from the familiar Edna St. Vincent Millay poem unfold across the room: "We were very tired/We were very merry/We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry."

With the long open wooden benches inside, the $2 beers and the magnificent views of the Statue of Liberty, Lower Manhattan and the boats in the harbor, the free ride is an appealing jaunt for tourists as well as an essential ride for commuters. Senator Charles Schumer found out just how appealing the ride is for visitors when he campaigned for reelection in 2004. He rode the ferry one day, shaking hands with everyone who was awake. "Hi, how are you? Where are you from?" he'd ask. England, France and Iowa were some of the answers that day. He chatted and quickly moved on, looking for constituents. After awhile, he turned to an aide, and sounding frustrated, said, "They're all tourists."

The tourists and the commuters (the commuters were probably the sleeping people that Schumer knew better than to wake up) know that despite the harrowing events just three years ago, and with more strict attention to safety, the Staten Island Ferry remains an integral part of the city's day.

Related Web Sites:

Staten Island Ferry, from the Department of Transportation Staten Island Ferry History, Facts

Â

Stuyvesant Town, Queens West And The Debate Over Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses

However else New Yorkers reacted to the sale last month of Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village, and to the announcement the same week that the Bloomberg administration would develop a new community on the “Queens West” site, it was inevitable that in the ensuing discussion some people would invoke the spirits of two larger-than-life figures in the history of New York City’s built environment – author and urban planning pioneer Jane Jacobs (who died on April 25th) and the city’s “master builder” Robert Moses (who died 25 years ago, in 1981).

This was inevitable because these two names are invoked nearly every week in debates about the future of New York City. Just the week before, in fact, the Gotham Center for New York City History presented a well-attended forum entitled “Jane Jacobs Vs. Robert Moses: How Stands the Debate Today?” which featured speakers ranging from the head of the New York City Planning Commission to the architecture critic of the New York Times.

But the Moses/Jacobs debate seems especially well-suited to Stuyvesant Town/Peter Cooper Village, since Moses actually played a substantial role in the building of these housing complexes, and Jacobs felt they were the antithesis of the “life on the street” that she adored in New York City. And across the East River in Long Island City, the 5,000 mixed-income housing units planned for the “Queens West” site would replace what would have been Olympic Village (had New York City been chosen to play host to the Olympics), reminiscent of Moses’ large-scale projects in Queens; his career was book-ended by the two World’s Fairs held in Flushing Meadows Park.

A closer look at both Stuyvesant Town and Queens West suggests the complications in using the usual arguments in the debate over Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses.

Has Jane Jacobs Won?

At the Gotham forum at CUNY Graduate Center, as throughout the city, Jacobs is generally praised and Moses is scorned. Neighborhood residents look at such projects as Atlantic Yards in Brooklyn, and see the kind of imperial efforts used by Robert Moses to roll over communities (as detailed in the biography of him by Robert Caro, The Power Broker). They cite Jacobs for her love of the “ballet of neighborhood life” and her opposition to planning from the top down, memorialized in her classic book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

“Jacobs has won the debate,” New York City Planning Commission Chair Amanda Burden declared at the forum, presenting the traditional view. (See her essay) The Department of City Planning, she said, now develops finely-grained, nuanced plans that seek to incorporate neighborhood feedback. Even when she plans for large-scale developments, she said, she imagines Jacobs looking over her shoulder.

But perhaps things are more complicated than they seem. Most of the presenters on the panel disputed the idea that “we are all Jacobs-ians now.” Richard Kahan (development czar under Mario Cuomo) agreed that "we are trying to have a diversity of uses where Moses was encouraging monolithic super blocks." But he argued that "we are still talking about mega projects, not bad, not good necessarily … but they are hardly paying much attention to neighborhood scale."

Other panelists presented revisionist views of the Jacobs vs. Moses debate. Columbia University professor Hilary Ballon argued that Moses got some important things right that Jacobs missed – especially a city’s need for large-scale infrastructure and large institutions such as universities. Ballon is curating a retrospective exhibition on Moses next year at the Queens Museum, the Museum of the City of New York, and Columbia. And two panelists (Samuel Zipp, a professor at the University of California-Irvine, and I) cited a paper by Damon Rich arguing that the image of “big plans and little people,” in which government planning is always seen to roll over neighborhood residents, has in many cases been used to give cover to conservative arguments that we ought to accept for our cities whatever the “free market” gives us.

Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village

At first, Stuyvesant Town/Peter Cooper Village might seem to follow the usual argument. The 11,500-unit development was created through eminent domain – pushed through by Moses – that displaced several thousand residents in a low-rise, tenement style, mixed-use neighborhood. It was planned from the top-down, built in “towers on the park” super-blocks, and has no street life. At the beginning, it was a segregated community; African-Americans were not allowed to live there.

And yet five decades later it is seen by most residents and planning observers as a supremely successful place. Community life thrives within its interiorized open spaces. And while it has not become the city’s most diverse community, it has become an enclave for the middle-class within a sea of far more expensive and socially homogeneous luxury housing.

From one angle, the recently-announced purchase of the property by Tishman Speyer from MetLife shows just how successful the property has become. The issue now, of course, is not about whether Stuyvesant Town is a planning affront, but how to save it as a middle class community. The purchase price of $5.4 billion can only be supported by substantial increases in the rents, by taking units out of rent regulation over time. The offering circular for the sale suggested that the complex could be converted from 75 percent rent regulated units now to only 30 percent rent regulated by 2018.

The same offering circular also proposed several ideas that might be seen as “bringing Jacobs back in” -- improving the retail mix along the streets, and perhaps the creation of new buildings that might better integrate with the grid -- as ways that potential buyers could bring in higher-paying tenants and increase the value of the property.

The threat to diversity in this case, then, comes not from top-down planning but from the marketplace. In fact, the only thing that has preserved a more diverse, more middle-income community at Stuyvesant Town is government action and regulation. The affordability requirements that came with the tax breaks MetLife received to build the property expired decades ago. Since then, it is only rent regulations that have kept the units affordable. And it is the weakening of those laws that has made the sale possible. In 1994, the New York State legislature began to allow “vacancy deregulation,” by which units can be taken out of the rent regulation system upon vacancy once their rents exceed $2,000 – and increasingly, landlords can deregulate units that rent for several hundred dollars less than this through major capital improvements.

Queens West

The proposed development of Queens West is also more complicated than the traditional “Jacobs vs. Moses” debate frame would suggest. The development will likely be in high-rise towers with a master plan created by City Hall – the type that Jacobs would likely have scorned: In 2005, just a few months before her death, she wrote a scathing critique of the Bloomberg administration’s similar proposal for the Greenpoint-Williamsburg waterfront just to the south. Yet local residents, community board leaders, and elected officials all praised the proposed development of the site. The most popular element of the plan is that it would provide housing for the “middle class,” for households earning from $60,000 to $145,000 each year.

The proposed development of Queens West is also more complicated than the traditional “Jacobs vs. Moses” debate frame would suggest. The development will likely be in high-rise towers with a master plan created by City Hall – the type that Jacobs would likely have scorned: In 2005, just a few months before her death, she wrote a scathing critique of the Bloomberg administration’s similar proposal for the Greenpoint-Williamsburg waterfront just to the south. Yet local residents, community board leaders, and elected officials all praised the proposed development of the site. The most popular element of the plan is that it would provide housing for the “middle class,” for households earning from $60,000 to $145,000 each year.

It is important to note that the proposed development hardly serves the diversity of Queens. More than 60 percent of Queens residents earn less than $60,000 – so most of Queens two million people will not be able to afford even one of the proposed 5,000 “affordable” units. A diverse set of Queens community organizations, known as Queens for Affordable Housing, is calling for a far better mix, with half of the units affordable to families earning less than the Queens median income of $48,000.

Here, as in Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village, it appears that what communities fear is less mega-projects imposed by the government than market-led development that creates luxury housing that only the wealthiest New Yorkers can afford.

Neither Top-Down Nor Natural Evolution Of Markets

It is not simply income and racial diversity that is in question. New York City’s growth and consequent market-led real estate pressures are putting strains on the quality of life of neighborhoods in every corner or the city – more traffic, more people using scarce open space, overcrowded schools in many growing neighborhoods, tear-downs of historic structures.

The answers will not be found in Moses’ style top-down mega-projects, which led to massive increases in traffic and were in many instance contemptuous of the very poor families they were serving (although he did create more open space that anyone before or since).

But the answers also won’t be found – as some who invoke Jacobs’ name today try to do – in seeking to prevent development altogether, nor in diminishing the role of government in city-building. New York City is expected to grow by one million people (mostly as a result of immigration) in the coming decades. We need thoughtful city planning and smart, activist government to make that growth work for New York’s communities.

To keep the city diverse and affordable, we’ll need not only more investments in affordable housing, but also strengthened rent regulations to enable those who are here already to stay. To preserve mixed-use communities, we need stronger zoning provisions that allow manufacturers to survive in the city. To make the new jobs created by all this growth and development pay enough for a family to live in the city, we’ll need “living wage” regulations that make sure we aren’t using our tax dollars and public planning to subsidize poverty wages.

To address ever-increasing traffic – in a region that already has the longest commute times in the nation – we are going to need both “congestion pricing” (charging people something when they drive in Lower/Midtown Manhattan) and investments in more transit infrastructure. To truly improve quality of life and create more green space, we will need to de-map some of the area we now give to streets, to let pedestrians have more room in their neighborhoods.

Many of these issues will be at stake over the next few months as the Bloomberg administration begins to reveal more about the work of its newly created Office of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability (profiled in Gotham Gazette’s land use column).

As the new office begins its work, it might take heart in looking neither to Jacobs nor to Moses – but instead to two efforts in the Bronx. At the Kingsbridge Armory – after many years of organizing by the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition – the New York City Department of Economic Development recently sought proposals for a 575,000 square foot redevelopment to include a mix of retail, entertainment, recreational, and community uses. Several schools will be developed in an adjacent campus. For the first time, City Hall agreed to favor developers who commit to pay a living wage to workers. Unlike the displacement of the Bronx Terminal Market last year for a large-scale retail mall, when many community groups and small business advocates criticized the administration, in this case there was praise from all side.

Two miles to the southeast, residents of Soundview, Hunts Point, and West Farms are open to an even larger development. The Southern Bronx River Watershed Alliance – a coalition of four community organizations and three citywide groups – have proposed the demolition of the Sheridan Expressway, an unnecessary blight on the neighborhood built, of course, by Robert Moses. This summer, through a series of community planning sessions, they developed a plan for something far grander in its place: a mixed-use, mixed-income development that would include thousands of units of housing; new commercial, retail, and community facilities; and new open spaces.

The (hopeful) lesson: we don’t have to choose between top-down Moses mega-projects (that accommodate growth but undermine communities) and the natural evolution of markets in places like Jacobs’ West Village that may preserve neighborhood character but results in a neighborhood that very few can afford. When people are truly included in the planning, when development comes with real and more fairly-shared benefits, and when smart public policy helps shape growth to make it work for neighborhoods, communities can be willing to accept large-scale development and shoulder their share of the city’s growth.

Brad Lander is the director of the Pratt Center for Community Development.

Â