Can Small Stores Survive in New York?

With large national chain stores having solidly established themselves in much of the city, Duane Reades and other discount drug stores occupying spaces once used by mom and pop businesses, and banks appearing on every street corner, many locally owned shops have shut their doors. Recently, the Municipal Art Society sponsored a panel discussion on locally owned retail in New York City: Can it survive and what can, or should, be done to save it.

The following comments are excerpted from the discussion.

Creating a Market

By Irwin Cohen

The 8 million people in New York City are being jumped on by the 292 million people who live on the mainland of the United States. They are trying to push their retail ideas on us, and it’s not good. We have to stand up to this, keep our neighborhoods strong and keep merchants in business. But we can do it. The opportunities are unlimited.

Even with the chain stores, you can still go into the retail business and be successful in New York. Maybe we have to cede the rights to have these mall-type stores in Manhattan because, if I’m a landlord and I can get a chain or a bank or a pharmacy to pay a high rent, I would probably think about it. But there are great facilities available in the Bronx and in Brooklyn. There is always something in each neighborhood that is available and can be developed.

You should take some of the parking garages around the city, get rid of them and let the city make that into space exclusively for small businesses. We don’t need cars. We don’t need parking. We have fantastic public transportation. If we got rid of cars and took all the lots and made those into locally owned retail we could go some place. We could set up pushcarts again. We would be healthier, and we would be able to have great shopping.

Chelsea Market

Chelsea Market provides an example of how this can work.

In the middle of the 1990s I was fortunate enough to find the old Nabisco buildings on the West Side. And I was even luckier to have investors in Tashkent, Uzbekistan and in Siberia. When I told them what we had purchased for them in Manhattan, the Russian said, “Aha, the capital of the United States.”

They allowed me to do what I wanted to do with respect to the ground floor of the building. At that time, we would hold meetings, with engineers, architects and construction people. My architect was from Holland. He lived in New York. My structural engineer was from Ireland. He lived in New York. My electrical engineer was form Russia. He lived in New York.

At these meetings, I was the only one who was born in New York City. And I realized one of the great strengths of our five little boroughs is their ethnic diversity. And I said we have to take advantage of that.

And we have to run counter to what everyone else is doing. I was able to convince my investors that just making a lot of money from retailing was not the function of a great, old building of historic significance in New York City. There was something more that the people had to have. So my daughter and I, working together, set some standards.

We said first, every one of our tenants has to be a family owned business, at least half of the businesses have to be female owned, the owner of each business and its executive offices have to be located in Chelsea Market, and the tenants have to be both wholesalers and retailers. That is because when the economy in the city was good, their wholesale business selling to restaurants would be good. But when business slowed down, as it did after 9/11, the tenant could stay in business because their retail operation would cater to the people who were not going out to restaurants.

It was a bit crazy, but it was a social experiment. You have to have a social conscience. But it worked out very, very well.

It was a bit crazy, but it was a social experiment. You have to have a social conscience. But it worked out very, very well.

We have Manhattan Fruit, which did business out of a truck and a very small freezer on 15th Street before it came with us. The Fat Witch Brownies operated from her kitchen. And the man who makes the gift baskets ran his business from his living room.

If you create a market – a concentration of people in similar businesses – you can create stability and establish a location where people will feel comfortable shopping without name stores. Every single tenant in that building that started nine or ten years ago is still there. Our biggest problem is that we don’t have enough room.

The market has to be an experience. At Chelsea Market, you are walking through a street that happens to have a roof on top. I kept it very cool in the winter and warm in the summer because you have to feel as if you’re outside.

We located the tenants haphazardly. Each was chosen for a very, very strong reason. “Can you get what this tenant makes any place else?” And if the answer was no, that was the tenant that we wanted. And that’s why people come back.

We created a neighborhood by having the owners on premises. If you had a little complaint about any of our tenants, they would be in your face in 30 seconds. “You don’t like the recipe? My grandmother used this recipe. She used it in Russia. How can you say it’s no good?” And the owner would take you into her kitchen and show you the ingredients and how she prepares them.

We brought all of the production to the front where people could see it. When we first opened, I could gauge the amount of customer activity and acceptance by the number of nose prints on the glass in front. People would come in with notepads and become specialists in cooking. People come in and watch today the way Amy puts her bread together. And it works.

There was no standard for entrances. I said just keep it clean and decide how you want to run your businesses. The last thing that can fail is where you run your business. You’ll give up your home before you give up your business because you have to eat.

La Marqueta

And there are other opportunities, An example: La Marqueta under the elevated Metro North tracks going up from 111th Street. The state Economic Development Agency said, “Give us some ideas about what we can do to bring La Marqueta back.”

I said, “It’s a good idea, but two blocks of La Marqueta is not the answer. You need a mile of La Marqueta.” And they said, “How are we going to fill it up?”

So, we went into a store on 116th Street where the people were from Senegal. The owner sold leaves that people press at home and use to make tea. And I said, “I have a new business for you. You’ll set up a tea shop and you and all the people that we get into La Marqueta will develop a market – a concentration of wholesalers and retailers.” With that, the owner said something in his language and his entire family came out from behind a curtain – they were living in the store – and one of them said, “I will translate. My father will go to work in La Marqueta and my mother and I will stay here, ”

That’s New York. We can do it.

Hunts Point

I am now working in the South Bronx, in Hunts Point, trying to change the way Hunts Point conduct its retail business. In the next six to a year, you will see what I’m planning to do. We are going to have hundreds of family-owned businesses operating. I’m trying to use that as a model for the rest of the city.

There is plenty of business for everybody. We have many great people in this city who know how to cook and how to sew and how to weave but they don’t have the opportunity to show their wares so they work as bricklayers and they have to work in factories. They could run their own businesses and train their families.

But for it to happen, there have to be people who are willing to take the risks and go against the 292 million people who are generating these malls. It can be done.

--Irwin Cohen is the chief of ATC Management and developed Manhattan’s Chelsea Market.

A Will To Preserve Character

by Victor Dadras

New York City is a city of neighborhoods. We have recognized there is an issue, if not a problem, and that is the loss of the character of those neighborhoods.

Once every neighborhood has the same stores -- Starbucks, Rite Aid, Papa John’s Pizza, and all the others – there is no reason to go from neighborhood to neighborhood. It happens now when you travel. Eat at a TGI Fridays in Salt Lake City, it is like eating at the ones on Long Island. New York City is, along with Boston and Philadelphia, one of the older cities in North America, and we need to be at the forefront of preserving character, which is ultimately what makes people who visit New York come back to shop.

The problem is once you put the independent druggist out of business, where is he coming back from? Once Home Depot and Lowe’s put out the local lumberyard, they’re gone.

We do not have a plan or a vision to address this. The city operates on a reactive basis. Everything we are talking about is a reaction to something that we don’t like, something that is happening to us, to our neighborhood, to the local stores, the corner drugstore, etc.

City property is a perfect example of this lack of vision. City property is always used in my recollection to maximize profit, not to preserve character.

There are many things that can be done. First there must be a will to preserve character. My firm has worked with some communities where people didn’t even think they had a “character.” It was being lost due to ignorance and neglect. So the first thing we need to do is educate communities as to what they actually have. We meet the community and work with them on what they see their neighborhood’s character as being: What do you have? What do you see as the positives, what would you like to improve, how can we best preserve what you have?

But once you have a vision, you develop guidelines. There are certain zoning regulations –- not in New York City -- that prohibit banks on corners. You can have incentive zoning where you try to encourage things or zoning regulations where you discourage things. You cannot tell someone what they can’t do with their property, but you can guide development.

The same criteria Irwin Cohen used for tenants in Chelsea Market can be used by communities, if they are organized, working with the city and the state to help with funding and with regulations and guidelines to help preserve the neighborhood character that makes a place special.

I like the fact that these are independent, hard-working, mom and pop stores and retail that I want to support. That’s why I live in New York.

--Victor Dadras's architecture firm works with neighborhoods to preserve the character of their downtowns and their main streets.

Â

Waterfront In Fits And Starts (And Stops)

If a revitalized waterfront is part of the vision of the current mayoral administration, with projects planned throughout the city, progress has been spotty, beset by squabbles, cost over-runs, reversals or simply inaction. .

Minerva's View

The tale is that the statue of Minerva in Green-Wood Cemetery waves at the State of Liberty in New York Harbor. The nine-foot goddess of wisdom has been sending that greeting since 1920. That's when her bronze form was put up at this highest point in Brooklyn to commemorate a Revolutionary War battle.

When a developer tried to put up a condominium tower at 614 7th Avenue at 23rd Street in Brooklyn that would block the view between the two statues, people in the South Slope neighborhood protested.

At 70 feet, the tower would be taller than the 40 feet the new zoning allowed. But the developer Chaim Mussencweig argued that he had laid the foundation for the building before new zoning went into effect. The tower should be grandfathered in on the old zoning rules.

On September 12, the city Department of Buildings denied his appeal. The building will have to abide by the new zoning rules, and Minerva can keep waving at her big green buddy in the harbor.

It wasn't just for sentiment's sake that neighbors argued to limit the tower. They wanted to maintain a neighborhood of modest-sized residences. Minerva's shield helped win that battle, and now residents have new zoning laws that will keep them safe from marauding high rises.

Belt Parkway Path

After bumping through Brooklyn streets past the hurly burly of apartments and businesses, the Belt Parkway always provides a welcome view of open water and the lofty Verrazano Bridge in the distance. A 13-mile path along the shore to the bridge gives residents of Bay Ridge a place to walk and bike. It was the location for a love scene in an iconic Brooklyn movie, Saturday Night Fever. But like the film, the path shows its age.

The seawall deteriorated badly over the six decades since it was built on landfill, and last summer, the Parks Department closed a two mile stretch of the walkway in order to rebuild it. Cost was estimated at up to $14 million, to be completed by this summer. Complications of backed-up sewers that caused soil erosion delayed the project, now costing more than $20 million and scheduled to be done this month..

Political complications also ensued. Republican Congressman Vito Fossella took credit for getting the project going and for getting $5 million in federal funds.

In a speech in August, his Democratic opponent Steve Harrison said that Fossella waited years too long to spur the repairs, and that he never actually received the federal money. All of the funding came from the parks department.

The issue is likely to remain a factor in the campaign. It'll be worth watching to see each of these candidates for Congress try to prove how much more he cares about a waterfront park than his opponent. Since the city parks department is in charge of the Belt Parkway paths, a Congressional representative won't have much control over the project. But if park advocacy becomes a viable campaign issue, it might be a charming election season in Bay Ridge.

Ikea and the Graving Dock

This isn't a case of paving over paradise and putting in a parking lot, as the lyrics go. It's the case of paving over a gritty piece of Brooklyn's waterfront industry to put up a parking lot.

To some, that might not sound like a bad thing, replacing a noisy, dirty industrial site in Red Hook with a big store that sells good-looking furniture at good prices.

But to some people who work in the waterfront's oldest profession – shipping -- the loss of a graving dock to repair ships is a truly bad idea.

Built in 1867, the dock is a clever structure. A ship floats into the watery parking spot, a door slides shut behind it, and pumps drain the water so that the ship can be repaired. At more than 700 feet, the dry dock can accommodate large ships. Replacing it would cost a fortune.

There's only one other graving dock in the harbor, and it's in New Jersey. Ships go to other ports for maintenance and only use one here for emergency repairs. As more and more ships come into New York Harbor every year, it's shortsighted to fill in a usable graving dock, argues Captain Andy McGovern of the Sandy Hook Pilots Association.

At this point, good arguments for the graving dock's preservation aren't likely to make a difference. The city changed the zoning from manufacturing, and the operator sold the property in early 2005.

Though Ikea is unlikely to take them up on their ideas, the Municipal Art Society offers a plan for accommodating Ikea and their parking needs and preserving the dry dock.

At present, Ikea may leave the outline of the graving dock as a historical relic. Industrial archaeologist Mary Habstritt says that would be like "the outline of a body after a homicide."

Hudson River Park

Hudson River Park from the Battery to 59th Street features smooth, well-marked walking and bike paths. It's a spine that is being filled out and dressed up with grass, trees, playgrounds, piers with vistas, boathouses, and sports venues. But the park is a work in progress, and the path to completion is not perfectly smooth.

The Hudson River Park Act of 1998 allocated state and city funding ($360 million so far) to remake the five-mile-long park from a stretch of derelict piers into a waterfront showplace. By rebuilding 13 piers, the plan respects the historic importance of the working waterfront.

Today, the completed sections show off lush lawns, pleasant playgrounds, and spacious piers.

The section adjacent to Greenwich Village opened in 2003. Clinton Cove Park at 54th Street opened last spring. A newly landscaped park and walkway opened in July from Battery Place (the west end of Battery Park) to Chambers Street. In mid-October, Pier 84 at 42nd Street (next to The Intrepid, the museum battleship) will open, becoming the largest public pier in Manhattan. It will feature a boathouse and a large fountain.

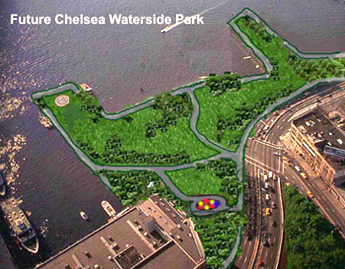

Work recently started on sections across from Tribeca and Chelsea. Two new piers will offer spectacular views. These are not quick projects. They should be ready by 2009.

There are growing pains. Pier 63 in Chelsea will be demolished and rebuilt as a public space. In order to start the work, The Hudson River Trust, which runs the park, evicted the commercial enterprises there.

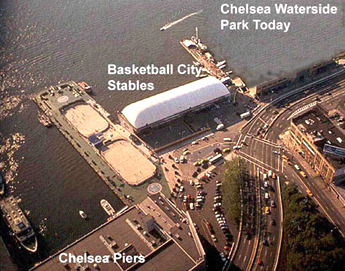

Basketball City, which occupied Pier 63 for nine years, fought eviction. Legal appeals gave them several reprieves over the years. But they lost their last appeal in August and had to vacate the pier by September 10.

Sixteen high schools from around the city and corporate leagues rented space in the six courts of the for-profit courts. Now Basketball City is scrambling for temporary space.

Another venture at Pier 63 knew that demolition was coming, but was still unprepared. When the Manhattan Kayak Company www.manhattankayak.com had to vacate the pier on September 10, it seemed to cut the boating season cruelly short. They had counted on Basketball City prevailing again, and they thought that the trust wouldn't throw them out so quickly.

The kayak company co-owner was philosophical about it: "The suddenness of this came as a bit of shock to us all as you may imagine, but we must adapt and continue as we always do," wrote Eric Stiller on the company's Web site.

In the meantime, the kayak company will work from the boathouse at Pier 96 (at 57th Street). Next year, the company will run their operation from 26th Street.

The pier also houses the New York Police Department's mounted unit, which will move its stables to another pier.

Lower East Side

Basketball City eventually plans to move to a pier on the East River just north of the Manhattan Bridge, one of three piers on the Lower East that are scheduled to be refurbished and opened to the public. The piers are currently behind tall chain-link fences.

Re-using the piers for new purposes is part of a larger plan to fix up the walkway/bikeway under the FDR drive adjacent to the Financial District, Chinatown and the Lower East Side. There is a biking and walking path under the FDR with glorious views of the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges, but beneath the highway next to the promenade along the river are parking lots, bad lighting and noise.

Funding for beautification is already there, in part from the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (from federal funding allocated in the aftermath of the attacks on the World Trade Center). The work has yet to begin, however.

City Councilmember Alan Gerson, who represents the area, says he's looking for an expedited timetable for the entire waterfront project along the East River. "We should be making better progress," he says. "We should not be going through 'hurry up and wait.'"

East River Park

Just north of the Manhattan Bridge, the park is still a mess, though rebuilding started on the walkway along the river last year. After contractors tore out the old promenade, soil from the muddy embankment began sliding into the river. The contractors placed bales of straw to stop the churned up mud from further erosion.

The work then stopped. Most of this summer, the construction site looked deserted, with heavy machinery sitting idle. Now, a parks department spokesman promises it will resume.

The delay did not attract much complaint from the neighborhood. The walkway has been closed since 2001, when it was deemed unsafe, so the community is used to living without it.

Carter Craft of the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance thinks the lack of community outrage at the stalled rebuilding has to do with how cut off the neighborhood is from the river on the Lower East Side. "They're so used to having crappy access," he says. He notes that there are just three pedestrian bridges across the FDR Drive to the park.

If construction stopped on the West side, where access is plentiful, says Craft, "they'd go nuts.”

Some on the Lower East Side explain the reaction differently. "The kind of development that happened on the West Side is the kind of development that’s going to raise rents and the cost of living, and I think there’s a huge part of this neighborhood that’s very scared of that," said David McWater, chair of Community Board 3 in Grand Street News, a neighborhood magazine. "They’d rather leave it alone because we don’t want everybody wanting to move here, because then I’m going to have to move to Iowa."

A Faster Track

The delay in the promenade construction led at least to one unexpected benefit. Since the landscapers couldn't work on the promenade, they transferred their energies to a runners’ track in the park at 6th Street. Runners will have their place to train in service at the end of September, well ahead of schedule.

Â

Housing Activists' Fall Agenda

While the scarcity of affordable housing continues to grab most of the attention when people talk about housing issues, advocates are pushing for answers to other problems. They have a full agenda for the fall, some of it a continuation of battles already begun – one is against the city’s flawed rent subsidy program, little more than a year old, called Housing Stability Plus, another is the effort to repeal the Urstadt Law, which prevents the City Council from strengthening rent regulation laws that affect about one million apartments in the city.

Building on the momentum housing issues have gained politically over the last year, though, advocates are now mounting new campaigns. In coming months some are hoping to persuade the City Council to pass legislation that would:

- Establish a “repair board” to enforce the city’s housing maintenance code

- Establish the right to counsel for senior citizens in housing court

- Make it illegal to discriminate against a person because of her or his source of income under the city’s human rights law

- Make it possible for tenants to sue landlords for harassment in housing court

Few advocates pretend that any of these issues will be easy to achieve. They are building support among a wide variety of groups for the inevitable political fights ahead.

Repair Board

For months John Williams has been trying to get his landlord to remedy a mold problem that is turning the floor of his Brooklyn apartment black. A tenant for 26 years who has always paid his rent, Williams has a problem that is far from unique in New York. Repair problems are as common in the city as cockroaches, which themselves are a problem that landlords are obligated to “repair” under the city’s Housing Maintenance Code.

When a tenant reports a problem to the city, an inspector is sent to confirm a violation of the housing code. That violation is entered in the Department of Housing Preservation and Development’s computer database and the landlord is then informed. And that’s usually where it stops. The exception is when the tenant – or the city’s housing department -- starts a lawsuit against the landlord in housing court.

“The current system isn’t working,” argues Ben Dulchin of Association for Neighborhood Housing and Development, which has spearheaded a campaign to make violations of the housing code like violations of the building code or the traffic code: Inspectors would be writing tickets and landlords would have to appeal to a newly created repair board, which would be an administrative tribunal.

“Just look at the statistics, Dulchin said. The Department of Housing Preservation and Development “writes 400,000 violations a year. About 25 percent are heard by a judge in housing court and most of those get corrected. But the other 75 percent are dealt with by sending a notice of violation … a polite suggestion to the landlord” to make a repair. “There is a misconception that notices of violation have teeth. They don’t.”

This explains why the city’s computers contain a list of three million housing code violations reported but never resolved.

The idea of a repair board has been around since the early 1980s, but got a boost recently when Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, the Democratic candidate for governor, expressed his support for its creation.

Landlords generally do not like this idea: “Anyone who thinks that penalizing the landlord is going to make more money available for repairs is fooling themselves,” said one landlord who asked to remain anonymous because he deals frequently with government agencies. “It’s going to mean less money for repairs.”

But some tenant attorneys feel the same way. The remedy a repair board offers “is not repairs; it’s fines,” said Susan Cohen, an attorney at MFY Legal Services. “The fine will be a cost of doing business. An administrative tribunal would have no authority to order repairs. It would just levy fines.”

Right To Counsel For Low-Income Senior Citizens

Of all the problems in housing court, none strikes more people as less fair than the uneven distribution of attorneys. While almost all landlords have legal representation, almost no tenants do. Free legal services available in the city are woefully under-funded and can represent only a small fraction of the people who qualify for their services.

For more than two decades advocates have sought to establish a right to counsel at housing court to remedy this problem. A small step in that direction is now under consideration: Establishing a right to counsel for low-income senior citizens in housing court.

“Housing laws in New York are very complex and on top of that the court system is difficult to navigate,” said Craig Acorn of the Community Service Society, one of the organizations pushing the proposal. “People who are brought to court on eviction actions are often very intimidated by those two things…. And landlords have an unfair advantage over those who are un-represented.”

Landlords have long opposed a right to counsel in housing court, arguing that giving tenants attorneys would be too expensive and slow down eviction proceedings. The court, they say, would need more judges, court personnel and space.

Acorn argues that the costs would be less than they are now. Evictions are expensive: “People who get evicted – in inordinate numbers elderly people – end up in nursing homes, hospitals, shelters,” he said. “One way or another, the city and state become responsible for their care. “And there’s an intangible benefit [to preventing their evictions] because we think that maintaining the character of a community and a neighborhood in large part depends on allowing long-term residents to stay where they’ve lived for years.”

Income Discrimination

The city’s human rights law, among the most comprehensive in the nation, outlaws discrimination in housing for a number of “protected classes.” One reason advocates say tenants are being forced out of affordable housing is landlords’ refusal to accept rent subsidies like Section 8 and public assistance. The answer is to update the city’s human rights law to prohibit discrimination based on “source of income.”

“It has become a very frightening way to push out long-term residents,” said Anne Lessy of the Pratt Area Community Council in Brooklyn. “Landlords are refusing to renew leases for tenants with Section 8 or other subsidies. And it’s harder for people to identify new housing opportunities if they receive income support or other assistance.”

The City Council is now considering legislation that would add source of income to the list of protected classes under the city’s human rights law.

The same landlord who cringed at the thought of a repair board was apoplectic at the thought of being forced to accept Section 8 and other rent subsidies: “The government behaves horribly in those programs,” he said. “I’ve had hundreds of bad situations. The city would be two years behind in paying. The city takes two years to figure out (a rent increase) and I’m supposed to go back and whack this tenant for two years rent?”

In fact, whether landlords should have to accept Section 8 in rent stabilized apartments – where leases automatically renew under “the same terms and conditions as the original lease” – has been a source of contention between landlords and tenants for a few years now. An appeals court decision is expected before the end of the year on this issue because housing court judges have come down on both sides.

But Lessy pointed out that other cities around the country have expanded their human rights laws to prohibit discrimination based on where their money is coming from.The answer to inefficient bureaucracies is not discrimination; the answer is to fix the bureaucracy, she said.

Suing For Harassment

When he was an organizer at the Fifth Avenue Committee in Brooklyn, Ben Dulchin recalls a landlord who put a bomb in the lobby of a building. The tenants filed an harassment complaint with the state’s Division of Housing and Community Renewal, which oversees rent regulated apartments.

“But (the division) said because he only planted one bomb, it wasn’t harassment,” Dulchin recalled. “Harassment, they said, was a pattern of behavior. That was the last time I filed an harassment claim with DHCR.” Dulchin is hoping the City Council will make harassment a “right of action” for tenants at housing court, allowing them the possibility of counter-suing when landlords file frivolous cases. Again, because landlords are almost always represented by attorneys, they do not have to go to housing court themselves. Most tenants do not get attorneys and end up spending hours at court, often losing at least a day’s pay as a result.

“We get calls from people who have been taken to court even though they’ve paid the rent,” said Jenny Laurie of the Met Council on Housing. “Some mechanism for getting landlords to stop suing tenants just to harass them would be good.”

It is not clear what punishments landlords would face for filing frivolous cases. But giving tenants the power to counter-sue for harassment would be a powerful deterrent against hauling tenants into court for rent that’s already been paid or subletting their apartments when all they have done is found a roommate.

Joe Lamport is the assistant director of the City-Wide Task Force on Housing Court, a coalition of community housing organizations. Â