Finding Space for a Million More New Yorkers

Which city in the United States added the largest number of people over the last 15 years? The answer is not Las Vegas. It's not Phoenix. It's not Dallas. It's New York City. New York City added more than 800,000 additional residents since 1990.

And, according to forecasts, this will continue. We expect that probably a million, and perhaps as many as a million and a half, additional residents will come to New York City in the next 25 years.

By then, the whole tri-state region, the already-crowded 31 counties in and around New York City, is expected to grow to 26 million people.

All these people will arrive in an area that is built to capacity in many ways under existing land use plans and regulations. We are already feeling ill effects of dramatic growth. Residents of parts of Queens, Brooklyn and Staten Island see every sliver of space in their neighborhoods being developed as pressure builds for taller buildings to house new residents. Our area now has by far the longest commutes in the country. And as some suburban areas pull up the drawbridge, making it very hard to construct multifamily or affordable housing, people who might choose to be in the suburbs are forced to live in the city.

Finding ways to accommodate even more residents will require public education and support. People have to understand that the city and region are going to grow, and it is either going to happen in a thoughtful way or it is in an unthoughtful way, an unplanned way.

Across the country, cities have come to realize they must join in a regional growth strategy that emphasizes public transportation, improving existing urban centers and creating new ones. Many have enlisted political, business and civic leaders as well as ordinary citizens in a dialogue about how to accommodate growth and at the same time respect the needs and fabric of existing communities. It is time for the New York region to embark upon this kind of effort.

WHAT OTHER CITIES HAVE DONE

Chicago provides a good example of how regional planning might work here. Mayor Richard Daley reached out to suburban mayors and built an alliance of elected officials from across the region to work on growth and transportation issues.

A new group, Chicago Metropolis 2020, initiated a regional visioning process. This basically involves harnessing new technologies such as computer mapping and computer generated visual simulations so people in an area can see what the alternative futures for their communities and regions really look like. It also employs electronic town meeting techniques like we used at Listening to the City in 2003 to help shape plans for lower Manhattan.

A new group, Chicago Metropolis 2020, initiated a regional visioning process. This basically involves harnessing new technologies such as computer mapping and computer generated visual simulations so people in an area can see what the alternative futures for their communities and regions really look like. It also employs electronic town meeting techniques like we used at Listening to the City in 2003 to help shape plans for lower Manhattan.

The first step is engaging public officials and citizens to define tangible goals for their region and to set benchmarks to measure their progress. In the second step, residents develop growth scenarios. People are divided into small groups of eight or ten and sit at small tables working with maps. It is a little like playing Sim City. Each group gets chips that represent the number of people and the amount of new development that needs to be accommodated.

Usually, participants start by spreading the people and projects out in very low densities. Half an hour later, they have run out of land. That is when they come back and stack up the chips. It is kind of magical: Citizens reach the conclusion that the only way to grow is by creating a new mix of density in their region and by developing existing and new centers. When they add up the number of cars that would be generated by spread-out development, they conclude that they must have alternatives to single occupancy vehicles.

Every place that has done this has ended up focusing development in new and existing urban centers. Many have concluded that if communities with just 2 percent of the region’s land area welcome development and accept growth, they can accommodate about 80 percent of the projected growth for the entire region.

And so, in Chicago, this exercise produced a set of recommendations about transportation investments and land use changes. The usual wars about where the third airport is going to be and so forth remain – it’s still Chicago after all -- but the participants have reached real consensus about patterns of growth and the investment needed to support major growth in the region.

An even more relevant example is the Los Angeles region. Los Angeles is, if anything, larger and more complex than the New York metropolitan area. The whole area is in one state but, politically, it is thoroughly balkanized.

People from throughout the region spent about two and a half years on the visioning process, and then they spent the last two and a half years working out a way to implement it. They reached consensus on a new regional transportation plan with a network of truck-only toll lanes on major freeways and of high occupancy toll lanes in key corridors. And they have agreed on a set of transportation investments across the region.

They also adopted some land use changes. The city of Ontario, California, which is an older industrial city with an eroding manufacturing base, decided it could accommodate a substantial amount of growth. They agreed to adopt zoning changes to allow for more residents, and the region agreed to make investments around Ontario’s airport and in a new regional downtown that will double the city’s population. When this is done, Ontario will have almost half a million people, a major new employment center and new housing.

Other cities in the region said they could not accept 30 or 40 housing units per acre, but they were willing to see what 20 would look like. And so they ended up with former industrial areas and strips being rezoned for mixed use, mixed income development.

Los Angeles is expected to grow from 18 million to 22 million people over the next 25 years. The New York region is going from 22 million to 26 million, so we need to think about following Los Angeles’ example.

SPACES IN THE CITY

Bensonhurst, Brooklyn

Finding space for all the additional people arriving in New York City will be hard because we have built on the easily developed vacant sites.

Throughout the city, people do not want additional development or additional density.

But there are still plenty of places to develop. The city has begun the process of rezoning in Greenpoint/Williamsburg, the Far West Side and so forth to prepare for additional population and employment growth. We have got a network of what the Regional Plan Association calls regional centers, places like Jamaica, Flushing, downtown Brooklyn and the Bronx Center. All of these have the potential to accommodate some additional development. And in the suburbs, areas such as the Nassau hub and Hicksville could be developed to house more people and jobs.

Queens, which is projected to add about a half million additional residents over the next 25 years, will have to accommodate more growth than any other place in the region. It has a lot of areas along the avenues currently dotted with one-story commercial buildings. Those plots could be recycled and more intensively developed. And we have the potential to expand Long Island Rail Road service in large areas of Queens that do not have subway service. Doing that would create some new development opportunities without adding to congestion.

If we can harness population growth and reinvest in existing and new urban centers we can improve mobility, create better development patterns in the region and heighten the economic prospects for our citizens.

For an example of why we should do this, we can look to Orange County, California. Twenty-five years ago, it was a very conservative place. It said, “We really don’t want a lot of immigrants and â€those people’ coming here.” They adopted a number of “pull up the drawbridge” zoning and housing regulations to prevent multifamily housing. They did not accommodate growth. But growth came anyway. People doubled and tripled and quadrupled up in single-family houses. This caused serious housing safety problems and other dilemma.

So planning for growth is essential. But the city cannot go it alone. Both New York City and its suburbs are in the same boat, and it will take collaborative action to keep as all afloat.

REGIONAL PLANNING IN NEW YORK

We have a number of assets to work with.

Demographic Changes: The baby boomers are aging, their kids are out of the house, and many are deciding to chuck the keys to those suburban houses and move into New York City and or another of the region’s older urban centers. At the same time, crime rates in the city have dropped, making the city a more attractive place to live.

Transportation: Over the last 25 years, we have invested more than $50 billion in the transit system. That has created a safer and more reliable transportation system in the core of the region.

We also have the largest regional rail system in the world. And in many ways the commuter rail system is not as intensively used as its counterparts in London, Tokyo, Paris and other world cities. There are many places where the density of development within walking distance of a station is relatively low. And so we have enormous potential to fill in development around this system.

To promote that, we have several very large transportation projects that are now partially funded, have full funding agreements with the federal government or are expected to get them. These include the East Side access project and the Second Avenue subway. The ARC project, including a new Hudson River tunnel, is coming along just behind them, and the rail link between lower Manhattan and Kennedy airport has partial commitment of state and federal funds and Port Authority funds. None of these projects, however, can fulfill its potential unless we coordinate land use and transportation around them.

Planning: Our area has strong public agencies, as well as regional organization such as the Regional Plan Association and the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council. This tri-state area also has a track record of successful visioning exercises, such as Listening to New York, at the sub-regional and local level

But there are obstacles as well.

We have one region as far as the business community and commuters are concerned. But unfortunately, King Charles II decided it would be convenient to make the Hudson River the boundary between the province of New York and the province of New Jersey. The province of Connecticut was just 30 miles away. Like plate tectonics, these three places that don’t really like each other rub up closely against each other. To make matters worse, we have 31 counties, and things get really messy when you drop in the political subdivisions: towns, villages, small cities, boroughs, unincorporated areas and so on. We are the most politically balkanized metropolitan region in the country. This makes reaching consensus on the major land use and transportation investment policies and investments a lot more difficult than it would otherwise be.

Flushing, Queens

And then there is history. Robert Wagner was probably the last mayor of New York City to reach out beyond the city’s borders. Through much of the last 25 or 30 years, New York City felt like the region is a zero sum game: If Nassau or the Jersey waterfront grew, city officials thought, it was at the city’s expense.

But that may finally be changing. I think Mayor Michael Bloomberg -- maybe partly because he ran a company that has operations in New York and New Jersey -- understands that we live in a region with an integrated economy. And the city has been doing really well of late, so there is a growing realization that there’s plenty of development and growth to go around. We are not managing decline here, we are managing success -- and that makes it easier to reach across the political boundaries.

As part of this whole regional planning process, we must build a broad base of political support around tough things: Finding the money to pay for the next generation of transportation investments. Making difficult land use decisions. Promoting growth.

Doing this right can produce many benefits. We can conserve the environment, create a mix of housing types and densities, and get the governance and tax reforms to make this work. It is hard to reach consensus around anything in this big messy place that we call home, but we must do it.

Robert Yaro is president of the Regional Plan Association.

Â

Residency Requirements

|

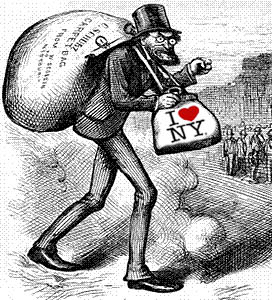

Carpetbagger |

As principal of Brooklyn Tech, one of the city’s largest and most prestigious public high schools, Lee McCaskill had been described as a “polarizing figure...ruling by intimidation.” But what eventually cost him his job was not that – but the fact that he lived in New Jersey.

Earlier this year, the Department of Education learned that, while McCaskill and his family lived in Piscataway, he sent his daughter to a highly regarded New York city public elementary school without paying, as the city requires of those who live outside the five boroughs. Under investigation, McCaskill resigned.

And McCaskill is not alone. In March, after McCaskill lost his job, at least 132 school employees told the Department of Education that they too lived outside the city, sent their kids to public schools and did not pay $5,500 a year tuition. But while some of those educators may gripe about having to pay to send their kids to free city schools, they can take solace in one thing: Unlike most other New York City employees, teachers can live wherever they want. Many city employees are required by law to live in the city itself and thousands more have to live in New York State.

It is apparent why the Department of Education sought to crack down on McCaskill and the other teachers. In essence, they cheated the city out of money as their children occupied seats -– usually in highly regarded schools -– that could go to bona fide New York City residents. But, in general, does it matter where a public employee or elected official lives?

NEW YORK’S POLICY: EXCEPTIONS RULE

|

Today, about 80 percent of all people who work for the New York City government live within the five boroughs, but this is far more than are legally required to do so. New York has a patchwork of laws and attitudes on residency requirements. While city residents voted overwhelmingly in 2000 for a senator who had lived and voted in Illinois and Arkansas, but never New York, the municipal government requires that a receptionist in the planning department live within the five boroughs. And while a teacher can reside wherever he or she pleases, a firefighter must have his or her home in one of 11 counties in New York State. Police Commissioner Ray Kelly must live in the city, but a beat cop does not have to.

The move for residency requirements gained force in New York City and much of the rest of the country in the 1970s. As middle class people fled to the suburbs, city officials struggled to keep as many salary-earning, stable people in the city as they could, and municipal employees fit that profile. Some officials argued that residency requirements would keep taxpayer money in the city rather than giving it to people who would use it to buy groceries and pay property taxes in New Rochelle. This argument still holds sway in poorer, more beleaguered cities, such as Buffalo and Detroit, but others question whether, in increasingly affluent New York City, the requirements have outlived their usefulness.

On a radio call-in program last August, Mayor Michael Bloomberg alluded to this. In the 1970s, he recalled, “there were forces to try to keep people in the city. Today we’ve got the reverse problem: Too many people trying to live here.”

The debate over residency requirements is as old as the country. "Every matter, and thing, that relates to the city ought to be transacted therein and the persons to whose care they are committed [should be] Residents," wrote George Washington in 1796.

And some residency laws date back centuries: In 1829, New York State enacted a law dictating that all firefighters live in New York. In New York City, the Lyons Law, passed in 1937, required city employees to live in the city. Under urging from Mayor Robert Wagner who called the law “inequitable,” the Board of Estimate repealed it in 1962.

By the 1970s, New York had a state law that said so-called public officers –- a vague term that includes people who have decision-making authority –- had to live in the jurisdiction that employed them. But the state expressly exempted from the law uniformed workers and those in independent agencies, such as the Metropolitan Transportation Authority or the Board of Education. (Teachers remain exempt even though the mayor has assumed control of the schools.) Over the years, the state has created some 70 exceptions to the rule, ranging from New York City sanitation workers to the dogcatcher of Onondaga County. As a result, city police and firefighters can live in the city, or in one of six surrounding New York State counties.

Mayor Ed Koch wanted all city workers –- even the exempt ones -– to live in the city, and the city passed a law doing just that. But the courts threw it out on the grounds that the city could not override the state law on uniformed employees. In response, in 1986, the city council passed a law that said any city employee hired after September 1 1986 and not exempted by the state laws had to live in the five boroughs. This law remains largely in effect.

DEBATING RESIDENCY REQUIREMENTS

In New York, the debate over residency requirements has involved activists on one side and employee unions on the other.

The Arguments For

Workers will be more available in emergencies: A commission appointed to investigate the violence that broke out during the 1977 New York City blackout cited a slow police response. It blamed this partly on the fact that, when the lights went out, many officers were at home in the suburbs, far from the streets of Bushwick and other hard hit neighborhoods. More recently, Bloomberg said that, if sanitation workers were allowed to live in the suburbs, it would be harder for them to respond promptly to emergencies, such as snowstorms. Ironically in New York City, many of the workers most vital to emergency response — such as police and prison guards – can live 90 miles away, while clerks and managers have to stay closer at hand.

City residents are more likely to understand and empathize with city residents: This argument is frequently raised with regard to the police department. “The hidden assumption, “the Times said in a 1986 editorial, “is that officers residing outside the city fall too easily into thinking of their patrols as â€occupation duty’ over an alien population.”

"If a person lives in the city, he can't help but have a greater feel for the city because he is here 24 hours a day," former Police Commissioner Lee Brown once said.

Following several fatal police shootings, as well as the police torture of Abner Louima, the Campaign to Stop Police Brutality, led by the New York Civil Liberties Union among other groups, called for a residency program “tied to an affirmative action plan for police officers to improve police/community relations” and increase the department’s effectiveness.

Following several fatal police shootings, as well as the police torture of Abner Louima, the Campaign to Stop Police Brutality, led by the New York Civil Liberties Union among other groups, called for a residency program “tied to an affirmative action plan for police officers to improve police/community relations” and increase the department’s effectiveness.

But others haved questioned whether it would make a difference. In 2001, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani said the city received fewer complaints against police officers who lived in the suburbs than against those who live in the city. “That doesn’t mean that police officers who live in the city are better or worse,” he said at the time.

But according to a 2001 poll (in pdf format) done by the City Council, 45 percent of city residents surveyed said requiring police officers to live in the city would be “very beneficial,” and 13 percent considered it “moderately beneficial.” Twenty-nine percent said it “would make no difference.”

Hiring city residents would create a workforce that, to paraphrase Bill Clinton, looks like New York: A study done in 1991 found that city residents applying for the police department were three times as likely to be Hispanic and four times as likely to be black as people applying from outside the city. If the city had to choose its employees from a pool of candidates where blacks and Latinos predominate, some argue, the workforce would reflect that.

Taxpayers’ money should stay in the city: People who work in the city do not live here do not have to pay city income tax or a commuter tax – it was eliminated in 1999.

The Arguments Against

People have a right to live where they want: This position sounds powerful, but the courts have not accepted it. In 2004, for example, the state’s highest court rejected the claims of a city maintenance worker who challenged the city’s residency law. And in 1989, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the state courts and ruled against firefighters challenging the law that required them to live in New York State.

The courts seem to agree with a former mayor of Madison, Wisconsin, Paul Soglin who told Governing magazine, “People have a constitutional right to live anywhere they want. They do not have a constitutional right to public employment.”

The city is too expensive: Unions raised this objection when the city first moved to enact stricter residency requirements in the 1970s, and it has gained force today as middle class people find it increasingly hard to rent or own a home anywhere in the city, which represents many maintenance workers, clerks, technicians and other municipal employees who must live in the city, has said it is unfair that some of the lowest paid city workers are the ones who must live in the most expensive part of the metropolitan area.

Residency rules keep the city from getting the best employees: Hiring only people who live (or are willing to live) in the city narrows the pool of applicants from which the city can choose. When city school districts found it increasingly difficult to find qualified, certified teachers, many districts that had residency requirements for educators abandoned them. “With such a teacher shortage throughout the country, most districts are trying everything they can to attract teachers rather than create barriers,” a spokesperson for the American Federation of Teachers has said.

The rules are difficult to enforce: Some cities have resorted to spying. Buffalo has had a residency sleuth who conducted on site surveillance and interviews with neighborhoods to root out employees violating that city’s rules.

In New York City, some government agencies have asked some workers to sign affidavits and, in some cases, employees may blow the whistle on other employees. It seems likely the teacher’s union, which had been warring with Brooklyn Tech principal McCaskill, may have alerted education department officials that he lived in New Jersey.

THE EFFECT ON SPECIFIC PROFESSIONS

Whatever the merits of these arguments, residency requirements, and the debate about them, play out in different ways, depending upon the job.

Firefighters

Residency is a particularly sensitive issue in the fire department. Despite frequent vows by the city to diversify, the department remains 92 percent white and almost entirely male. And about half of all firefighters live outside the city. Some advocates argue that requiring firefighters to live in the city would bring more blacks and Latinos to its ranks.

Residency is a particularly sensitive issue in the fire department. Despite frequent vows by the city to diversify, the department remains 92 percent white and almost entirely male. And about half of all firefighters live outside the city. Some advocates argue that requiring firefighters to live in the city would bring more blacks and Latinos to its ranks.

For now, though, like police officers, firefighters must live in one of 11 New York counties: the five that make up the city along with Nassau, Suffolk, Westchester, Rockland, Putnam or Orange. Changing that would require action by the state legislature.

The department does give preference to city residents, adding five extra percentage points on to the department’s entrance exam. But according to Paul Washington, president of the Vulcan Society an organization of black firefighters, many people claim to live in the city when they do not. The additional five points “would have an impact if it was really enforced,” Washington says, but “it’s easy for candidates to get around it,” and the department “seems to find it impossible to come up with a residency criteria that really works.”

A 2001 audit by the city’s Equal Employment Practices Commission agrees that residency requirements might help bring people other than white men into the department. It cited an array of reasons for the department’s homogeneity, including a failure to verify residency claims. But the corrections department has the same residency requirements as the fire department, and has a uniformed force that is more than 80 percent black and Latino.

Sanitation Workers

Since 1986, city sanitation workers have had to live in the city. But late last year, the state legislature said that sanitation workers, like police and firefighters, could also reside in six other counties. The workers “are ecstatic,” Harry Nespoli, head of the Uniformed Sanitationmen’s Association, told the Daily News after Governor George Pataki signed the bill easing residency requirements. “They want a piece of the American pie. They want to own a home.”

Since 1986, city sanitation workers have had to live in the city. But late last year, the state legislature said that sanitation workers, like police and firefighters, could also reside in six other counties. The workers “are ecstatic,” Harry Nespoli, head of the Uniformed Sanitationmen’s Association, told the Daily News after Governor George Pataki signed the bill easing residency requirements. “They want a piece of the American pie. They want to own a home.”

Bloomberg, though, expressed irritation at the state’s intruding in what he saw as city business. “I don’t think any of these things should be up to the state legislature,” he said on the radio at the time. “It should be the city negotiating with its unions and the state should stay out of it -- whether it’s medical benefits, pension benefits, where you can live or any of those kinds of things.”

Elected Officials

Perhaps because so many New Yorkers come from somewhere else, voters here have accepted politicians from elsewhere. When New York was filling its first Senate seat in 1789, a Long Island native lost out to Rufus King of Massachusetts.

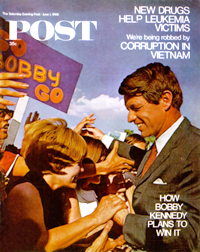

And in the years since, voters seem unfazed by politicians branded as Carpetbaggers, to use the term first coined to describe the Northerners who went South after the Civil War. Robert F. Kennedy became a New York senator even though he had spent most of his adult life in Massachusetts and Virginia. Hillary Clinton followed successfully in his footsteps more than 30 years later.

This year, people question whether William Weld was a carpetbagger when he ran for governor of Massachusetts, where he had lived for a number of year, or whether he is a carpetbagger now as he seeks to become governor of New York, where he grew up and has kept a summer home.

But some politicians have stumbled on the residency issues. Councilmember Bill deBlasio met with some derision earlier this year as he pondered whether to run for a congressional seat from Staten Island; the district includes a sliver of Brooklyn, but not the Park Slope area where deBlasio lives (and which he now represents in City Council).

But some politicians have stumbled on the residency issues. Councilmember Bill deBlasio met with some derision earlier this year as he pondered whether to run for a congressional seat from Staten Island; the district includes a sliver of Brooklyn, but not the Park Slope area where deBlasio lives (and which he now represents in City Council).

DeBlasio decided not to enter the race, but his City Council colleague David Yassky continues his quest to represent a congressional district, which his home is close to but not in. (To remedy the problem, Yassky recently moved.)

And residency requirements can offer an opportunity for the canny politician. Take Brooklyn Assemblymember Roger Green. In 2002, Green faced a vigorous challenge from lawyer Hakeem Jeffries. Green won but did not want to risk facing Jeffries again. So, when the state legislature set about redrawing assembly districts, Green made sure they moved the boundaries of his district by one block -- just enough to put the Jeffries home outside of it.

And now? Jeffries and his family have moved so they will be in the district. And Roger Green is running for Congress, to represent a district where he has lived for many years.

Â

Stadiumania: Snapshots of an Obsession

When a new Yankee Stadium (above) was approved by the City Council one day before the Mets unveiled their design for a new stadium in Queens (below) last week, it was just the latest episode in New York City’s sports building frenzy.

Nine sports teams in the metropolitan area –- the Yankees, Mets, Knicks, Rangers, Jets, Giants, Devils, Islanders and soon to be Brooklyn Nets –- all have plans to build new venues. And there are even plans to build a NASCAR race track in Staten Island.

Together, the projects will cost more than $5 billion and require hundreds of millions in taxpayer subsidies. The plans have also sparked vigorous debate over jobs, the use of parkland, and traffic –- and whether public money would be better spent elsewhere.

In an effort to win over New Yorkers, the baseball teams in particular aren’t just arguing that their new stadiums are good for the city’s economy - they are trying to appeal to feelings of nostalgia in a town where baseball was born, the first ballpark hot dog was served, and some Brooklynites still mourn the loss of a team that left a half a century ago.

"I almost feel like I'm walking through the rotunda, 8 or 9 years old, holding my dad's hand,” said Mets chairman Fred Wilpon, his voice cracking as he described the new stadium design meant to evoke memories of Ebbets Field, where the Brooklyn Dodgers played until they left for California in 1957.

Click Here for a Photo Essay on New York City Stadiums and the Issues Surrounding Them

Â