Are Higher Rent Increases Justified By Rising Costs

The Rent Guidelines Boardgave preliminary approval for the highest allowable increases for rent-stabilized leases since 1990. If approved in the final vote to be held on June 19, one-year leases will rise 5.5 percent, and two-year leases by 8.5 percent, beginning October 1, 2003.

The board’s justification for the large increases lies heavily in one of the reports they issue annually – the Price Index of Operating Costs(pdf format). That report looks at the costs for a market basket of goods and services needed to operate and maintain rent-stabilized apartments in New York City.

The 2003 price index jumped 16.9 percent, largely due to sharp increases in fuel costs, insurance premiums, utility prices, and taxes. Labor costs, contractor services, administrative costs, parts and supplies and replacement costs showed more modest increases. It was the second highest price index increase in the 35-year history of the report.

Landlord representatives argued that higher prices proved the need for higher than usual rent increases, while tenant advocates discounted the price index entirely.

The 2003 Price Index of Operating Costs

A handful of factors came together over the past year to cause the spike in the price index.

Fuel Costs – Up 66.9 percent

The price of heating oil (chart) began rising last November, just as cold weather set in. Those higher prices and a colder-than-usual winter combined for an unprecedented one-year increase in the cost of heating a typical rent-stabilized apartment.

The cold weather accounted for about 40 percent of the cost increase. The remainder came from the rising price of crude oil, which made itself known at gas stations and beyond, as it neared $40 per barrel.

Insurance Premiums – Up 40.5 percent

It wasn’t just the losses of 9/11 or the fears of more terrorist attacks that boosted insurance premiums for city landlords last year. Wall Street’s poor performance played a big role. Just like hopeful retirees across the country, insurance companies watched their reserves deplete as the stock market dropped and scrambled to refill them with higher premiums.

But 9/11 did cost insurers $ 40.2 billionand made them more reluctant to stay in the New York City market. And owners who increased the insured value of their properties, or added terrorism coverage faced premium increases of almost 50 percent.

Utility Prices – Up 21.7 percent

Natural gas and electricity costs rose by more than 40 percent over the past year. They both correlate to rising crude oil prices. Natural gas can be used as a substitute for heating oil, and high oil prices increased demand and price of natural gas. And both oil and natural gas are common feedstocks in the production of electricity.

While water and sewer costs rose minimally over the past year, the New York City Water Boardrecently passed a price increase of 5.5 percent, effective July 1, 2003.

Taxes – Up 14.8 percent

The strong housing market has meant that assessments of property value have gone up. Furthermore, the city’s 18.5 percent property tax increase was implemented in January. Property owners are now paying more and hoping to pass along the increase to renters.

While these numbers would seem to support the need for higher than usual rent increases, tenant advocates caution that they are not the whole story. First, they say, the price index only looks at changes in prices, not at actual landlord expenditures. Previous Rent Guidelines Board studies have noted a difference, since landlords find ways to economize when prices spike.

Secondly, “It only looks at one side of the profit equation and ignores income,” said Michael McKee, associate director of New York State Tenants & Neighbors, a statewide tenant organization. While the Rent Guidelines Board does consider income and expense studies(pdf format), they use data which is outdated by the time the board makes its annual decisions on rent increases. Landlords should be required to submit real-time income and expense reports for the Rent Guidelines Board to consider in its calculations, tenant advocates say.

“We reject the price index methodology entirely,” said McKee. “It is fundamentally one-sided.” In support of this notion, a bill was recently introduced in the City Council to bar the use of the price index in the determination of rent increases. For this year, however, “we are hoping we can persuade a majority of the [Rent Guidelines] Board to lower the number for the final vote,” said McKee.

Half a percentage point or a percentage point could make a big difference for tenants. Even the relatively modest 2 and 4 percent increases that were adopted last year resulted in a citywide rent increase of $174 million in the first year. “That’s a transfer from a million-plus tenants to 25,000 landlords who include some of the wealthiest people on the planet,” said McKee.

But landlord advocates are also hoping to persuade the board to alter the numbers before the final vote. They would like to see bigger increases than the current proposals.

“It’s totally inadequate, given the extraordinary increases in costs that owners have experienced in the last year,” said Frank Ricci, director of governmental affairs of the Rent Stabilization Association, the city’s largest residential landlord group.

Landlords have greater faith in the accuracy of the Price Index of Operating Costs, although, they point out, the numbers always lag a year behind rent increases. They had asked for rent increases of 9 and 15 percent for one and two-year leases respectively and were disappointed by the lower numbers the Board voted through.

“For a certain segment of property owners, it’s going to be extremely difficult,” said Ricci.

Rebecca Webber is a journalist who has covered housing issues for Gotham Gazette since July 2000.

Fixing Urban Irritants

|

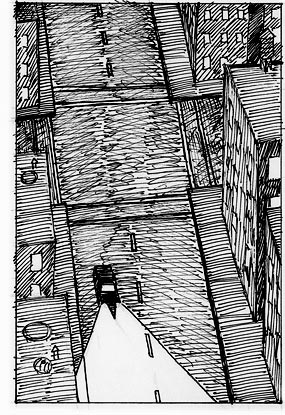

A pothole that rivals the Grand Canyon.

Buses that seem to never come and then arrive in a herd.

The residential street used as a drag strip.

Such irritations may not pose the same threat to the fabric of society as failing schools and homelessness but they cause sleepless nights, fray tempers and add to a general feeling that life in New York is tough, mean and even unsafe.

In March, the city unveiled its 311 hotline to make it easier for New Yorkers to complain about such nuisances. Rather than navigating a maze of phone numbers, a call to a single number — 311 — brings an answer from a real person who can, at the very least, tell the caller how to gripe constructively. Since its launch, an average of 8,385 calls have come in daily to the 24 hour a day hotline where they are fielded by 201 agents who can speak 170 languages.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg advises New Yorkers to take advantage of the hotline. "If you see a pothole, what do you do? 311. It's very easy," he said.

At a time when New York is suffering through what the Daily News has dubbed "the worst pothole crisis in history," many calls are indeed about road conditions.

In general, roads score high on the list of New Yorkers' urban frustrations. In a 2001 survey on how New Yorkers would rank city services, one third said road conditions rated a "poor." And 40 percent said they were bothered by dangerous traffic in the city. Noise also stands out as a persistent irritant.

But despite the mayor's enthusiasm for his hotline, 311 is not a magic bullet that will solve all of this. New Yorkers need dogged determination to get some problems fixed — filling out forms, conducting research and forming alliances. Even persistence, though, does not guarantee success.

City crews may be slow to respond to complaints. Government officials may find, justifiably or not, that the stoplight or traffic light is not needed. Or the solution to the problem may not fall in the city's jurisdiction, being instead the responsibility of Con Edison, say, or the state government. Other problems defy quick or easy fixes. Budget cuts almost guarantee that in some cases the city will be slower to respond — if it responds at all.

Of course, your City Council member and community board will also listen to complaints — and sometimes act upon them. Gotham Gazette's new Community Gazettes provide you with the opportunity to find out what needs to be fixed in your neighborhood — and to voice your own gripes.

Here is a selection of common New York irritations, why they persist and what average citizens can — or cannot — do about them:

• Potholes

• Bus Bunching

• An Intersection in Need of a Stop Sign

• Problems with Traffic Lights

• Speed Bumps and Humps

• Dark Streets

Dark Streets

At a recent party, residents of the Ditmas Park neighborhood in Brooklyn shared their strategies for walking home from the Cortelyou Road subway station after dark. Some simply get off at the next station on the line. Some take circuitous routes, going out of their way to avoid one block of Marlborough Road. And a teenage boy talks to his parents on his cell phone until he gets to another block, hoping to quickly alert them to any problem.

At a recent party, residents of the Ditmas Park neighborhood in Brooklyn shared their strategies for walking home from the Cortelyou Road subway station after dark. Some simply get off at the next station on the line. Some take circuitous routes, going out of their way to avoid one block of Marlborough Road. And a teenage boy talks to his parents on his cell phone until he gets to another block, hoping to quickly alert them to any problem.

Marlborough Road between Cortelyou and Dorchester is not a hotbed of crime. But it is extremely dark.

The entire tree-lined block has only three street lights, compared to four on the next block. The block became more forbidding last year when a bar on the corner — whose feeble light spilled out a bit on the dim sidewalk — went out of business.

Most urban resident equate light streets with safer streets. Tourist guides and tips on how to live safely in the city advise people to avoid dark streets. Specific crimes, including the rape of the Central Park jogger, have been blamed on a lack of lighting.

Astronomers and sky gazing enthusiasts say that street lights make it difficult to see the night sky. They note that while in theory as many as 2,500 stars could be visible in a typical night sky, a person standing in midtown Manhattan is likely to see no more than 15. And lights can glare into apartments and homes, keeping people awake.

But the barriers to adequate lighting in New York are less likely to be concerns about light pollution than issues of cost, wiring and maintenance.

The Department of Transportation is responsible for installing and maintaining 325,000 New York City street lights. Its electric bill alone for the lights totals $50 million a year, according to department spokesperson Lisi de Bourbon.

The 311 city hot line handles complaints about broken street lights. A person can also file an on-line complaint form. The form lists more than 30 things that can go wrong with a street light from being burnt out to having exposed electric wires, shining in the wrong direction, or missing the door at the lamp post base.

People filing a complaint receive a work order number that enables them to check on the status of the job in the days ahead. The department says that its streetlight maintenance contractors must respond within 10 days of being notified of a problem. That does not mean, though, that the contractors have to repair the problem within that time. Instead, they can, for example, note that the job calls for a major repair — such reconstructions of the lamppost's concrete foundation — or refer the problem to Con Edison.

Complaints do get results. According to a recent article in the Bronx community newspaper the Norwood News students in a local middle school action club noticed that a number of street lights were out in the Williamsbridge Oval. "The lights are important because it keeps bad people out of the park," club member Chris Rambarran told the paper.

And so the club began a telephone campaign to get them fixed. It took eight rounds of calls to the transportation department but, the lights went back on and the club received a letter from the transportation department, lauding the role it played.

Getting a street light installed involves a different procedure. The transportation department web site provides no form for this and an operator at 311 had to look into the issue before advising a caller to send a letter to transportation commissioner Iris Weinshall.

But Terry Rodie, of Community Board 13 in Brooklyn, which includes the Cortelyou Road subway station, says improving lighting can be "an easy thing to take care of." Once the request is made to the transportation department, it brings in equipment to measure the light on the street in question and determine whether it is sufficient. Although Rodie said she was not familiar with the Marlborough Road block, she said foliage on trees can make a block seem darker. And she said light from any commercial establishment on the block is also taking account.

In deciding whether to grant the request, says de Bourbon, the department follows guidelines set out by the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America. "It's really more scientific than you think," she says.

The "real hang up" in improving lighting, says Rodie, is not the city but Con Ed. "They have a backlog with this kind of thing."

(Do you have dark streets or broken street lights in your neighborhood? Tell us about it by going to the Community Gazette for your area.)

-- Gail Robinson

|