Filling In The Potholes

Â

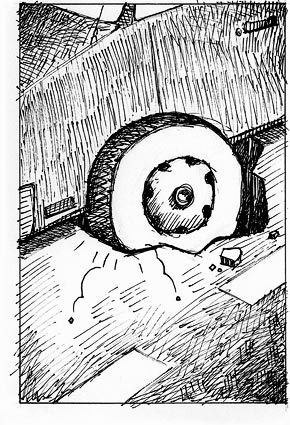

Michael Gilpin is an aspiring actor with a day job in Manhattan, a shared apartment in Astoria, and a car with a blown suspension system. In February, while driving home from a friend's house in Brooklyn, the front tire on Gilpin's silver Geo Prism fell into a fissure on the Van Wyck Expressway in Queens — a classic pothole notable primarily for its size, which he estimates at about 18 inches deep.

Michael Gilpin is an aspiring actor with a day job in Manhattan, a shared apartment in Astoria, and a car with a blown suspension system. In February, while driving home from a friend's house in Brooklyn, the front tire on Gilpin's silver Geo Prism fell into a fissure on the Van Wyck Expressway in Queens — a classic pothole notable primarily for its size, which he estimates at about 18 inches deep.

"I fell off a shelf into an abyss," Gilpin says. "I felt it in my throat. I was in flight." He pulled to the side of the road to investigate. "The tire was flattened. Pieces blown. I had a spare. I had a jack. I had my girlfriend watch for my life."

For city drivers like Gilpin, potholes are a fact of life. He and his friends refer to the pothole-riddled area around the entrance to the Queensboro Bridge as "Saigon."

"It's almost unmanageable," Gilpin said.

A winter such as the one that just ended wreaks havoc with pavement in the city. It spurred the Daily News to declare the current situation the worst pothole crisis in the history of New York, to run an ongoing feature entitled Pothole of the Day, and to feature fissures such as one on 78th Street in Middle Village and on Morrison Avenue and East 174th Street in the Soundview section of the Bronx.

According to Department of Transportation spokesperson Tom Cocola, from February to mid-April, the city repaired approximately 53,000 potholes — 18,640 in February alone. That is a 50 percent increase from 2002. After the Presidents Day snowstorm, the city launched what Mayor Michael Bloomberg called "a pothole blitzkrieg," filling approximately 1,600 potholes a day.

But with so many miles of streets and highways in the city, simply figuring out what to fill where presents a challenge. The transportation department counts on its 40,000 workers to look out for potholes. The department also relies on average New Yorkers and provides several resources for pothole victims to report a problem, vent their frustrations and even get reimbursed by the city for car damage caused by a street defect.

One of the fastest ways to report a problem is through the Department of Transportation web site.

The new 311 hotline for non-emergency complaints is supposed to make it easier to complain about potholes. From March 9 to April 21, 2003, the hotline received 3,526 pothole related phone calls, according to the New York Times.

After the mayor said he was "tired of people complaining" about potholes and directed them to phone 311, calls to the hotline about road defects jumped 400 percent, according to the Daily News.

But the transportation department wants details: the precise location of the problem, its size and depth, a description and so on. To help, its web site provides a detailed breakdown of the different kinds of street defects. Is your street plagued by a hummock — a bump resulting from the road being pushed up? Or is it the site of a cave-in, a jagged break in the pavement with a large void beneath? Photos of these problems, as well as of traditional potholes and protruding manhole covers, help readers understand what, exactly, popped their tire or loosened their chassis.

The department tries to repair each reported defect within 30 days. But it has not always succeeded. An audit released in November found it took an average of 57 days for the transportation department to repair potholes — 98 days for defects in the Bronx.

The city promised in late April that it would have about 35 crews of three to four people each working to repair potholes for 10 days. The Daily News followed one crew recently and found it spent little time working, preferring to shop, buy and eat food, and drive around aimlessly. The transportation department suspended the workers after the story appeared and said it would also take disciplinary actions against four supervisors.

The transportation department web site also offers a link to the city comptroller's office, where residents can report car damage sustained from a brush with a pothole and try to get reimbursed.

While the city blames the particularly harsh winter for the current pothole epidemic, budget cuts may make a bad situation worse as the Department of Transportation cuts back on street renovations that could prevent future potholes. "You never fix a pothole by just filling it," former transportation commissioner Lucius Riccio, who now teaches at Columbia University, has said. "You have to fix the street. A pothole is an indication that the street is failing."

The gloomy prognosis would not surprise Michael Gilpin who sees the pothole as being as much a part of driving in New York City as motorists who run red lights and summer weekend traffic jams on the Long Island Expressway in Queens. "It's an ongoing nightmare," says Gilpin. "I don't drive through Manhattan without expecting potholes."

(Do you have a pothole problem in your neighborhood? Tell us about it by going to the Community Gazette for your area.)

-- Anne Sachs

|

BAM And Its Cultural District

As a high profile institution that has managed to attract a great deal of public and private funding, the Brooklyn Academy of Music has for years been a lightning rod for community activists leery of the "high" culture -- such as ballet, symphonies and opera - that it is world-renowned for showcasing. Although situated on the borderline between commercial downtown Brooklyn and residential Fort Greene since 1908, BAM (as it is universally called) has recently come to represent the front line of the Manhattan-style development invasion that seems to be slowly rising out of the East River like an occupying army, threatening to subsume Brooklyn skylines and life-styles forever.

Perhaps nothing calls into question the role that large cultural institutions play in the development of neighborhoods more than BAM's $700 million plan to build a new 14 square block cultural district. The BAM Local Development Corporation has been working on the details and financing of this district for years, but things recently came to a head when community activists demanded to have their concerns included in the BAM Local Development Corporation's plans, causing public officials to threaten to pull the project's public funding.

The fear is that the BAM district will import new housing, businesses and cultural facilities and essentially re-engineer the cultural personality, not to mention residential and commercial real estate markets, of Fort Greene. Specifically, community activists are calling for the details of plans to be made public, and for those plans to reflect locally articulated economic development visions and needs.

The process BAM and community activists use to resolve this matter over the next few weeks -- BAM will begin meeting within the month with the Coalition of Concerned Citizens, a Fort Greene grassroots group, to try to work out an agreement -- will do more than determine if BAM can secure public funding. It will serve as a negotiation for Fort Greene's cultural soul. In this instance, the term "culture" is a fig leaf for issues we do not like to name explicitly -- particularly race and class.

In other words, we are faced with a question: Will BAM use its expansion as an opportunity to further engage and support the kind of culture Fort Greene is well known for -- a racially integrated, funky avant-garde flava -- or is BAM striving for a more homogenized, euro-centric kind of sensibility, consumer taste and artistic expression?

An eclectic colony of performing art events, restaurants, up-and-coming artists and students -- a pulsating, multi-income Mecca that attracts people from all over the world and incubates talent and creative energy from the surrounding area -- is an exciting vision. An enclave of overwhelmingly white, privileged residents, artists, merchants and their patrons on the order of the Upper West Side is not. A clue to which the folks at BAM might prefer is evident in a comment by Harvey Lichtenstein, the chairman of the BAM Local Development Corporation: "The life and activity around Lincoln Center make me slobber at the mouth."

David Vine, a PhD student in cultural anthropology who has written extensively on the nexus between cultural and economic development, suggests that BAM's plans are a Trojan horse hiding an economic and racial takeover of Fort Greene. "This is not unique," Vine says. "If you look at the history of neighborhood development and similar projects around the country you'll see that 'cultural development' is a precursor to the displacement of large numbers of low-income people." Vine goes on to say that because it's "hard to argue against and oppose the bringing of culture, this kind of development often masks other interests, particularly commercial ones".

Although BAM is better known for cultural events that require high priced tickets and playbills, to be fair, BAM's offerings also include less high brow poetry slams, world music concerts and Dance Africa, a week long celebration that also features an African-styled outdoor marketplace. Also, what complicates the argument against BAM is that some of its most outspoken community critics are solidly middle class, people who have, perhaps more quietly, already helped make Fort Greene a trendy, pricey neighborhood.

Yet, no matter what your income or race, if you live, work or even pass through Fort Greene it will be impossible not to be affected by what is being proposed. The BAM cultural district has the power to not only completely transform Fort Greene as we know it, but send ripples across Central Brooklyn. The latest fact sheet I've seen issued by BAM promises 1.56 million square feet of development including a visual and performing arts library, a 350 seat theater, 100 units of market rate housing, 250 units of subsidized units and a boutique hotel.

My experience in community development tells me that BAM's negotiations with community activists and elected officials will follow the typical patterns of appeasement, but ultimately the larger commercial interests will prevail. BAM, at least if it is savvy and/or cynical enough, will do just enough to make sure the "community" has a voice in the process, promise local people jobs and retail space, give safe harbor to some local artists and cultural institutions and allow some folks from the hood to shack up in some of the "affordable" housing slated to be built.

It is just a shame that cultural change -- whether it occurs on the West Bank or the Upper West Side -- is so often reduced to an equation of us versus them, light-skinned against dark-skinned people, the haves and the have mores. New York is capable of so much more nuance and possibility. There are very few neighborhoods in this city - yes, Fort Greene included - that couldn't stand to be more diverse in its makeup, more tolerant to change and less parochial in its thinking. It's now up to BAM to prove this is the kind of community it seeks to build.

Mark Winston Griffith, a writer whose work has appeared in the New York Times, Essence and Spin, is also founder of the non-profit Central Brooklyn Partnership, which organizes people to build economic power.

To read more about Fort Greene - and to contribute your own news and views, as well as reports of potholes - go to the Fort Greene Gazette, the first of our Community Gazettes.

Zoning To Protect Manufacturing

The city is putting together a vision of the future that involves making changes to zoning in order to transform many neighborhoods. This includes:

- revitalizing the North Brooklyn waterfront with parks, housing and ferries

- converting Manhattan’s far west side into a mix of new offices and apartment houses, sports and tourist destinations,

- rejuvenating Lower Manhattan as a mixed residential, business and cultural community

- creating a new central business district in Long Island City.

Unfortunately, many of these proposed zoning changes collide with some of the most dense concentrations of manufacturing jobs in New York, risking thousands of jobs and potentially reducing the diversity of the city’s economy.

For example, in Long Island City the number of industrial jobs is actually increasing, but Long Island City is nevertheless the target of rezoning, the second rezoning in two years. This subsequent rezoning will increase real estate speculation that has already pushed rents for industrial space through the roof and risk displacement of thousands of jobs. It also risks the factories that build the stage sets and sew the costumes for our cultural and entertainment sectors, the printers who support our financial services and media, and the food processors who help make New York the culinary capital that attracts tourists and feeds our office workers.

In North Brooklyn, one of the other areas targeted for re-zoning, more than 20 percent of the residents who work have manufacturing or other industrial jobs. This community will be profoundly impacted if these jobs disappear, even if replaced by jobs in other sectors that pay significantly less.

The plans to rezone the Far West Side of Manhattan to create a mix of offices, residences, a stadium and expanded convention center will impact dramatically on the Garment Center, portions of which are within or border the rezoning study area. The Garment Center is home to more then 39,000 apparel jobs. These apparel jobs, many of which are in design and marketing, anchor an industry that employs 110,000 people and that is spread city-wide.

The potential for displacement does not necessarily mean that the city should stop its zoning initiatives. The city needs to rezone some areas. However, at the same time that it encourages new development it also needs to put in place new zoning and economic development tools to minimize the risk of real estate speculation and the loss of jobs.

Whatever the conventional wisdom of a few years ago, the truth is, New York City needs its manufacturers. There is a growing disparity in income between the richest New Yorkers and the rest of the city’s population, and this is due in some great measure to an economy increasingly dependent on a narrow range of industries. These industries pay their most highly skilled workers very well but they produce relatively small numbers of decent middle- and moderate-income jobs. The loss of manufacturing jobs and the drop in unionization are part of this trend.

The average annual production wage is $28,250 -- $10,000 more than average wages in retailing, the sector that is often pointed to as an alternative source of employment. Manufacturing jobs are also more likely to offer health coverage and to be accessible to people who would have difficulty finding decent jobs in other sectors. For example, almost two thirds of the manufacturing workforce is immigrant.

The well-being of many local economies depends on a healthy manufacturing sector. Manufacturing is viable in New York City. Seven of the ten largest cities in the United States experienced an increase in manufacturing jobs during the 1990s. Inc. Magazine, in collaboration with the Initiative for a Competitive Inner City, recently listed its one hundred fastest growing inner city companies and almost one third were manufacturers.

New York City manufacturers have adapted to New York’s demanding environment. Most are small, entrepreneurial businesses that take advantage of New York’s incredible density, creating competitive advantages for businesses that need to be close to their markets, suppliers, design talent and skilled workers. They can even thrive in multi-storied, multi-tenanted buildings, which may be obsolete for the type of manufacturing more characteristic outside the city, because these dense buildings place the manufacturers at the center of their markets.

At present, New York City does not have the land use tools to promote diversity. One might think that having the least restrictive zoning which permits the greatest variety of uses would foster diversity. It is more likely, however, that it will lead to homogeneity as every property owner seeks the greatest economic return on his own property. For example, in an MX Zone, the type of zoning which is increasingly being used by the city, both housing and manufacturing are permitted without restriction, and over time housing will price out manufacturing. The manufacturing that gives the area its character, acts as a buffer against gentrification and gives employment to local residents, will be lost. Diversity, both of physical form, economic activity and even demographic group, may suffer.

The city needs to create new types of zoning that promote diversity. One new zoning tool should be stable mixed residential-manufacturing zoning. In such areas both uses might be legal and manufacturing could be converted to housing, but a critical mass of manufacturing might be preserved through a dedication mechanism. A possible model is the Garment Center, where someone who converts manufacturing space to other uses must dedicate an equal amount of space for manufacturing. This zoning has helped to preserve more then 8,000 production jobs in Midtown Manhattan.

The city also needs to create a new type of manufacturing district. In some sense, New York City doesn’t really have manufacturing zones. It has zones where many uses can locate, including manufacturing, waste transfer stations, pornography, homeless shelters and offices. The city has even tried to put superstores in manufacturing zones. In many instances, the result of this free-for-all is speculation that undermines business investment.

Planned manufacturing districts (or PMDs) would be limited to industrial uses, their ancillary office uses and the neighborhood retailing that supports a manufacturing area. Such districts promote growth by providing the stability that companies need to make investments. Having planned manufacturing districts would also allow the Department of City Planning to target new development to certain areas without setting off speculation in adjacent areas. These manufacturing districts do not prevent change or preserve companies that are no longer viable businesses. Within such a district competition continues between permitted uses. One area in downtown Chicago has experienced a five-fold increase in the number of jobs since it was designated as a planned manufacturing district.

When the city rezones an area or allows the conversion of manufacturing space to other uses, the value of the property can increase dramatically. The city should recapture a small portion of this windfall through a fee or special assessment that can be used to help stabilize businesses in the adjoining areas and help companies that are displaced. This can be done on a building by building basis, as was the case under the Industrial Retention and Relocation Program run by the Business Relocation Assistance Corporation, or it can be done on a district basis similar to an assessment for a business improvement district.

Finally, the city must build the capacity of not-for-profit organizations to engage in the development of industrial space. Such ownership can insulate tenants from real estate pressures to convert manufacturing space. Rents still increase in response to increases in costs, but not speculation.

The city has already begun to recognize the need to promote a more diverse economy. Manufacturing provides better quality jobs for less skilled workers than other sectors which have already gained greater public attention. Supportive land use policies are absolutely essential to achieve a more healthy economic mix that includes manufacturing.

Adam Friedman is the executive director of the New York Industrial Retention Network