The State Of NYC Housing, According To The Census Bureau

The mayor and the city Department of Housing Preservation and Development have released preliminary results (in pdf) from the 2002 New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey. The U.S. Census Bureau conducts this survey every three years, primarily to determine the rental housing vacancy rate, which must remain below five percent in order for rent regulation to continue.

The vacancy rate, measured between February and June 2002, was 2.94 percent. In the 1999 survey, the rate was 3.19 percent, although the 2002 data has not yet been weighted to allow accurate comparisons to data from previous years.

"We still face the problems of a serious housing shortage, affordability, and crowding because the city is a desirable place to live," said Mayor Bloomberg in a press release that accompanied the release of the data. He said he supported the rent regulation laws as they exist today. Those laws are set to expire this June, and a heated battle will surround their renewal.

Beyond the rental vacancy rate, the survey offers a vast array of information about housing. The preliminary information currently available (the full tables will be released in about a year,) includes some surprising and revealing things about the city's housing stock.

Just what those numbers reveal, however, might depend on who you ask.

RENT

The survey found that in 2002, the median monthly gross rent was $788 for all units. For non-regulated units, it was $850, an amount that appears incredibly low, even for a housing market that has softened in recent years.

Location is one explanation.

"Most New Yorkers don't live in Manhattan, said Joe Weisbord, staff director of Housing First!, a coalition that promotes solutions to the city's affordable housing crisis. "[The $850 median] probably reflects a lot of apartments in the outer boroughs."

As was reported in Gotham Gazette's Issue of the Week entitled "The Fight Over Rent Control", another understanding emerges from a recent study by the tenant group New York State Tenants & Neighbors. The study analyzes data from the 1999 Housing and Vacancy Survey and among other things, calculates the median rent, excluding buildings with fewer than six apartments and single-family homes.

"If you include small buildings that have never been regulated, and homeowner neighborhoods in Queens, that's a very different kettle of fish, in terms of their location, their desirability, and in terms of landlord-tenant relationships," said Michael McKee, associate director of New York State Tenants & Neighbors Coalition. "We compare regulated rents and unregulated rents in buildings with 6 or more units, because to be rent-stabilized you need to be in a building with six or more units."

For 1999, their study found that the median monthly rent for rent-regulated apartments was $640. For unregulated apartments, it was $1090. In Manhattan, the numbers were $766 per month for rent regulated apartments and $2000 per month for unregulated apartments.

VACANCY RATES

The 2002 Housing and Vacancy survey found that rental vacancy rates varied by borough. For 2002, Manhattan's rate was 3.86 percent, the highest of the five boroughs.

"Manhattan is really a unique animal, very different from the housing market in the rest of the city," said Jack Freund, executive vice president and chief economist of the Rent Stabilization Association, the city's largest landlord group. "What you are seeing here is that the highest rent levels are in Manhattan."

Costly apartments tend to be in Manhattan, and the survey found that vacancy rates increased with rent levels. The rate for units asking $1750 per month or more climbed to 9.25 percent. For units asking $2,000 per month or more, the vacancy rate increased to 10.05 percent.

The stumbling economy might have something to do with those increases, but there are other possible explanations.

"There are more of those units coming onto the market, probably because of new construction in high rent units and vacancy decontrol of high rent units," said Freund.

Tenant advocates suggested that vacancy rates also remain high for higher rent apartments because those owners are often willing to keep their units vacant longer in order to find a tenant who is willing and able to pay.

VACANT APARTMENTS

The survey found that 2002 had the highest number of vacant units not available for sale or for rent since 1965, when the first Housing and Vacancy Survey was conducted. About 32 percent were unavailable awaiting or undergoing renovation, the highest number since 1987.

"That's a consequence of owners putting money back into their building, which they are able to do if they get rent increases," said Freund of the landlord group.

But tenant advocates thought renovations were a way for landlords to remove apartments from rent regulation.

"Landlords are spending lots of money on renovating apartments because with vacancy decontrol in effect, if you can get the rent above $2000 a month, you can take it from rent regulations forever," said McKee, of Tenants and Neighbors.

Also, 43,000 apartments, the highest number since the survey started counting them in 1978, were unavailable because of occasional, seasonal, or recreational use. More than six in ten of those apartments were in Manhattan.

Some attributed this to corporations that keep such apartments for the use of occasional corporate guests. But others saw it differently.

"It points out another structural problem with rent regulation that causes people to hold onto apartments even if they don't need them as their prime residence," said Freund. "We know that is a phenomenon that happens with apartments because the rents are so far below markets so you hold onto them even if you don't use them with the result that apartments are less available for the general population."

RENT REGULATION

Almost 22 percent of rent-controlled apartments were occupied by tenants who moved in after 1971, most likely utilizing succession rights. That means that nearly 80 percent of rent-controlled tenants have lived in their apartments since 1971 or before. In most cases, those tenants are now aging or elderly.

The data disproves the popular misconception that many of today's tenants under rent-control are lucky beneficiaries of family members' apartments.

"The reality is you can't just pass on your rent-controlled apartment to your nephew in Arizona," said McKee. "To have the right of succession, the family member has to actually live there. People who try to manufacture a situation that doesn't exist don't get away with it."

However, some see a problem in the long-term habitation encouraged by rent control.

"I think it speaks to the essence of the negative effect of rent control on the market. It takes units out of the housing market and reduces the general availability of housing for the majority of New Yorkers," said Freund.

Tenants in rent-controlled apartments actually seem worse off than their non-regulated counterparts. Their median income was $20,120 in 2001, less than two-thirds the median of all renter households. This can probably be explained by the advanced age and fixed incomes of such tenants.

"In fact, rent control incomes have gone up simply because the really old tenants have died off," said McKee. "In 1970 there were 1.1 million. Today you have 60,000, so it's a program that is being phased out."

HOUSING AND LIVING CONDITIONS: GOOD NEWS AND BAD NEWS

In 2002, housing conditions in the city were the best since the Housing and Vacancy Survey started asking about them. Housing advocates are pleased, but not surprised, by this revelation.

"I think you are looking at a century long trend in terms of improved conditions," said Weisbord of Housing First! "Housing conditions are, in general, extremely good, though there are still pockets of very poor quality housing in NYC."

As an example, the survey found that crowding remained a serious problem in 2002 — 11.1 percent of all renter households were considered crowded - with more than one person per room.

All in all, there are differing conclusions to be drawn from the revelations in the preliminary data.

"I think what is interesting is that housing remains very affordable," said Freund of the Rent Stabilization Association. He noted that the median household paid about 28 percent of their income in rent.

Tenant advocates, instead, focused on the continuing descent of the overall rental vacancy rate. "It is reflective of this very serious shortage that we have and we need to produce a lot of new housing and housing that is affordable for a wide range of income levels," said Weisbord.

Rebecca Webber is a journalist who has covered housing issues for Gotham Gazette since July 2000.

Waterfront Housing For Everyone

In my district in Brooklyn, there are acres of manufacturing land on the Greenpoint-Williamsburg waterfront slated for residential rezoning. Development of this land is expected to yield up to 10,000 houses and apartments in the next few years and dramatically alter the community. While new apartments are desperately needed in the area and the city as a whole, there is also a great need for affordable housing in this lower-income neighborhood.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg has announced an ambitious new housing plan, but because of the state and city budget woes — and federal government indifference — housing subsidies have been greatly reduced. To create enough affordable apartments in places like Greenpoint-Williamsburg, we must find new and innovative policy tools.

One possible solution is to link affordability to the zoning regulations by allowing developers to build slightly bigger if they dedicate some of their profit for the creation of affordable housing. In certain dense areas of Manhattan, a similar special zoning category already exists called, "inclusionary zoning." Developers who build residential apartments in these districts can build a little higher if they include a sizable percentage of the apartments for low-income households. The program has spurred the development of hundreds of low-income homes in the densest areas of Manhattan, but it has not yet been developed for use in less dense districts in the other four boroughs.

Some have argued that the program is not viable outside of Manhattan. However, I believe a modified version of the program could work on rezoned land – particularly those on the city’s attractive and highly developable waterfront. Land zoned for residential development is significantly more valuable than land zoned for manufacturing use, and so landowners on the Brooklyn waterfront will benefit financially with these changes. I believe that asking these developers to contribute some money to low-income housing is reasonable.

Some of the manufacturing land in Greenpoint-Williamsburg has already been developed for housing, though the property has not been rezoned. Developers of this land obtained a "use variance," the rights to build housing where they normally could not, by proving that they couldn’t make money if they complied with existing zoning regulations. Once again, the city is helping developers who will see the value of their property skyrocket. I propose, in the future, requiring these developers to commit to making 20 percent of new residential construction affordable for a typical family in the development neighborhood. Unused manufacturing land represents some of the last stretches of vacant land in the city. Unless the city intervenes, there is no guarantee that any low and moderate income New Yorkers will be able to live in any of the thousands of new apartments developed on these vast tracts. We cannot afford to ignore this opportunity to build affordable housing. The residents of New York City, not just the wealthy ones, deserve a chance to reap the benefits from the development of the Brooklyn waterfront.

New York City Councilmember David Yassky represents district 33 in Brooklyn.

Related Article:

Critiquing The Mayor's Housing Plan by Mark Berkey-Gerard

The Battle Over Rent Regulation

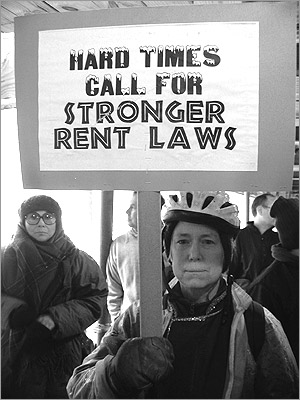

The rally outside Manhattan Housing Court last week started with a chant:

The rally outside Manhattan Housing Court last week started with a chant:

"What do we want?"

"Stronger rent laws!"

"When do we want them?"

"Now!"

It continued with speaker after speaker delivering passionate arguments, dire predictions and fiery exhortations:

"Let's get ready to rumble," one speaker said, while the crowd stamped and cheered in the cold. "We went through this in 1997. We're ready for them again. This is the next civil rights movement."

"I live in a rent-stabilized apartment," the speaker continued.

"I do too!" a few shouted out.

"I've been there for 48 years," the speaker said. "I grew up there. I'm not going anywhere!"

Anybody not well-acquainted with the war over rent regulation might have been surprised to see that most of the speakers being cheered at this rally — most of the speakers, period — were members of the oft-invisible New York State Legislature. (The rent-stabilized resident, for example, was Assemblymember Keith Wright from Harlem.) All those who were present represent New York City, and all of them railed against their upstate colleagues.

For millions of New York City apartment dwellers, the decision that will determine whether they can remain in their homes or be forced out will be made not by landlords across New York City but by legislators 150 miles away in Albany.

With the current law set to expire in June, it is time for the state government to decide whether to renew rent regulation. While the exact size of rent increases in most regulated apartments is determined by the city Rent Guidelines Board, the state government decides whether rent will be controlled at all and, if so, under what circumstances.

WHAT THE LAW DOES

Rent control began in New York in 1943, dictated by the federal government as a means to prevent rampant inflation during World War II. After the war ended and price controls were lifted, the state moved in, allowing municipalities throughout the state to control rents. Today, the state's rent regulations protect 2.5 million tenants living in more than a million apartments in New York City alone. Fifty other municipalities in the state also regulate rents.

Tenants leaders and other advocates see rent control as vital to insuring that New Yorkers, many of whom are life-long renters, do not lose their apartments because of the vagaries of the real estate market. Opponents argue that rent regulation interferes with the housing market, removing incentives for developers and landlords to create more housing. (See related story )

New York provides a variety of protections for tenants of rent-regulated apartments. The laws allow the city to put a cap on how much landlords can raise rents of occupied apartments. Currently, landlords in New York City can hike the rent by 2 percent for one-year leases and 4 percent for two-year leases.

In addition, landlords must renew their tenants' leases when they expire. And tenants have succession rights, meaning that they can pass their apartments on to a relative or a romantic partner. The rent laws also allow tenants to join tenant groups and fight for repairs without being retaliated against by their landlords.

THE LEGISLATIVE BATTLE

The battle over enacting new laws is already underway. Tenant advocates have begun organizing rallies and lobbying state legislators to ensure that when the June 15 deadline comes around, the new rent laws will provide better protections than the existing laws do. Landlord groups have generally urged the elimination of rent control.

In 1997, the last time the law came up for renewal, Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno vowed to end rent regulations. The Democratic controlled Assembly passed its own bill renewing the rent laws well before the expiration date. But the Republican Senate did not move to consider the issue until the deadline neared, giving the Senate the leverage it needed to weaken the Assembly's bill.

By the time the measure passed, it was so weak that tenant advocates claim that one way Albany could guarantee the end of rent controls is simply to simply renew the rent laws as they currently exist.

The state's top two Republicans, Governor George Pataki and Senator Majority Leader Joseph Bruno, have both come out publicly in support of renewing the rent laws "as is."

Such a renewal "would cause a slow death for the rent laws," said Democratic State Senator Liz Krueger of Manhattan who sits on the Senate housing committee.

The Democratic-controlled New York State Assembly got an early jump on the issue when it passed its rent-regulation bill on February 3. The Assembly's bill adds some tenant-friendly provisions to the current regulations and would be in effect until 2008.

Currently, controls on apartments are lifted when an apartment becomes vacant if that apartment can be rented for more than $2,000 a month. The Assembly bill, A.2716a, would end the that.

Tenant advocates see this as crucial. "If this is not repealed," said Dave Powell, an organizer at the city-wide tenant union Metropolitan Council on Housing (Met Council), "It will be the death of rent regulation in New York City." Tenant advocates estimate that almost 100,000 apartments have been removed from rent regulations since 1993 because of this provision.

Powell believes that, with the way rents are increasing in New York City, landlords will one day be able to claim that any apartment could rent for $2,000 a month, which would mean that all apartments would be exempt from regulation.

"If you are a talented businessperson you can absolutely figure out how to get your apartments out of rent regulation," Krueger said.

Landlords are now allowed to increase the rent of a regulated apartment by 20 percent when it becomes vacant and to add on one-fortieth of the cost of any renovations made while the apartment is vacant.

The Assembly bill would reduce the amount that landlords can raise the rent on vacant apartments — the so-called vacancy allowance — to 10 percent of the current monthly rent. It would place under rent stabilization apartments built since 1974 under the Mitchell-Lama program, which provided incentives to developers to build middle-income housing. The current regulations do not include any apartment buildings built after January 1, 1974.

Though the Assembly's bill is more tenant-friendly than the current laws, it does not go far enough for some tenant advocates. Powell faults the measure for not repealing the Urstadt Law, which bars New York City and the other 50 municipalities around the state that have some form of rent regulation from enacting rent laws stricter than those of the state.

"In effect, the law allows the city to weaken the rent laws but not strengthen them," Powell said.

The Assembly's bill now moves on to the Republican-controlled Senate where it is expected to take on a decidedly more pro-landlord look.

"The Republicans controlling the Senate are opposed to rent regulation," said Krueger, who hopes the Senate passes a bill identical to the Assembly bill. "My Republican colleagues from up state do not understand what a housing crisis is like and why we in the city need rent regulations."

A spokesman for Bruno, refusing to talk specifically about what the majority leader plans to do, would only say that the "New York State Senate is dedicated" to providing affordable housing to New Yorkers.

The Senate seems in no hurry to move on the issue . "We have several months before the rent laws expire," said Mark Hansen, a spokesperson for Bruno. "However, the Senate has a much more pressing deadline of April 1, when we need to have a budget passed."

"We are starting ahead of the game this year," Krueger said, noting that in 1997, Bruno was "publicly on record wanting to end rent regulations, but this year he wants to keep them the same." Hansen noted that Pataki also wants to keep the laws as they are now.

The Met Council and other tenant advocacy groups plan to keep the pressure are already organizing to put pressure on and push for stricter regulations. On May 13, "Tenant Lobby Day" in Albany, advocates will hold a rally and lobby legislators. And on June 1 — only two weeks before the regulations are set to expire — tenant advocates will hold a rally at Union Square.

Related Article:

Rent Regulation by Robin Reisig