Mafia: Rise, Fall and Resurgence

Selwyn Raab recently met with Gotham Gazette's Reading NYC Book Club to discuss his book Five Families: The Rise, Fall and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires, a history of the Mafia from its origins in Sicily to the present day. The following is an edited transcript of the event.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Mr. Raab, your book focuses largely on the fall of the New York crime families, but the title includes the phrase "resurgence." What's going on with the Mafia in New York City right now?

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Mr. Raab, your book focuses largely on the fall of the New York crime families, but the title includes the phrase "resurgence." What's going on with the Mafia in New York City right now?

SELWYN RAAB: Up until 9/11, there had been a 20-year long, concentrated attack against the Mafia, based on the Racketeer Influence Corruptions Act, popularly known as RICO. What was important about RICO was that for the first time it gave prosecutors an effective tool to go after the big shots in organized crime. At the attack's peak, there were 200 people working full time on just investigating the five Mafia families in New York -- the Gambino, the Bonano, the Colombo, the Lucchese, and the Genovese. The FBI had a specific squad following each family, and were able to bust John Gotti, Vincente "The Chin" Gigante, and other bosses, even though they didn't pull a trigger or shake anyone down themselves.

[This prosecution was coupled with a] concentrated effort to knock the Mafia out of some industries. Waste collection and construction were two immense moneymakers for them, and they've been hurt in both industries, especially commercial garbage collection. There is now some oversight by city agencies, licensing etc. The Mafia has been severely wounded in some of these big industries – but not mortally.

As soon as 9/11 occurred, terrorism justifiably became a prime concern and objective for the FBI and most police departments, including New York's. This created a reprieve – suddenly you had this tremendous diminution of people investigating the mob.

Today, the Mafia is still making money in gambling and loan sharking. The penalties for these crimes are very small, nobody goes away for a long time, and bosses are never brought up on charges. Still, this is terrific seed money to keep them going.

The Mafia is still very big on Wall Street, counterfeit credit cards, and phone scams. But a lot of the most recent action has been in the suburbs, where the theory is the local police departments don't have the expertise to stop them.

FORMING THE MAFIA

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Is there a fundamental difference between the Mafia and other types of organized crime?

SELWYN RAAB: We've always had organized crime groups – you had Irish and German gangs on the Bowery, Jewish bootleggers, the Italians, and so on. To oversimplify, prohibition changed all these gangs from street thugs to executives. The money was so big that they could expand, and when prohibition ended, they had big organizations to go into different things like labor racketeering.

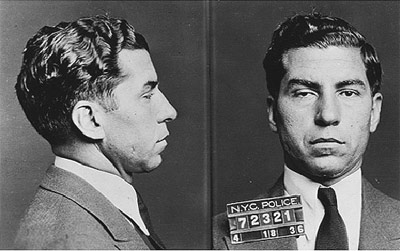

But the Italians had a business genius named Charles "Lucky" Luciano. Luciano saw the handwriting on the wall – prohibition was going to end, and what were gangs going to do for loot? He also saw the lack of a central organization. Luciano had a major convention [of Italian gangs] in Chicago in 1931, and said we can't have fights among ourselves anymore, because it's bad for business. He turned the Italian gangs into a semi-military organization based on what had been going on in Sicily, where each family had a boss, underboss, consigliere, and soldiers.

Charles "Lucky" Luciano

If you knocked out the leaders of the Jewish or Irish gangs, they dissolved, because there was no military setup. But Luciano set up the Mafia so that the individual is secondary to the organization; the theory was that the organization had to survive at any cost. If the boss died or was arrested, the organization replaced him, and he set up another hierarchy.

To stop disputes between families, Luciano created something called the Commission comprised of representatives from each of the five New York families. Immediately, they had more power than anyone else in the country.

Luciano also urged the Mafiosi to diversify their activities. Instead of having just gambling or loan sharking as other gangs did, they went into labor racketeering. They were a mirror image of capitalism: whatever works.

That distinction still exists today. The Mafia has such a lot going for it. The Latin Americans – Columbians and Mexicans – are into one thing: narcotics. They don't have the know-how to do these other kinds of crimes. Same thing with the Asian gangs, the Chinese. They may be involved in smuggling immigrants, or do shake down rackets on stores or restaurants in Chinatown and Queens. But they're not involved in other things.

THE IMPACT OF ORGANIZED CRIME ON NEW YORK CITY

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Why did New York City's Mafia families have such a disproportionate amount of power within the nationwide Mafia right from the beginning?

SELWYN RAAB: We can thank Benito Mussolini partly for this. The Mafia had always been very strong since it started out in Sicily in the 18th century, where people once thought of them as liberators because they fought against the foreign invaders, protecting the small farmers, peasants, and businessmen. They developed into a tyrannical organization, and they grew very powerful both politically and financially. When Benito Mussolini came into power, he saw them as a threat and started a crackdown. He rounded people up and put them in cages, sent them away for life, or killed them.

Because of this, a lot of the young Mafiosi in the 1920s emigrated to the United States, and the major place they went was New York City. They liked New York. It was very profitable. There was a big Italian American population, bigger than anywhere else. They settled into New York because they were welcomed here.

The curse of New York is that there are still five powerful Mafia families here. In the rest of the country it wasn't that hard to combat the Mafia – you just had to knock off one family and there would be no one around to fill their shoes. Here, if there is a devastating blow to one family, that vacuum can be filled by one of the others. They know if it's a good opportunity, and they'll take advantage of it.

PHILIP ANGELL: In New York City organized crime families were involved in a lot of very public rackets – the trash business, the construction business, the ready-mix concrete business. These were pretty open secrets for a long time. Do you have any sense of why this was tolerated by the political, financial, and law enforcement establishment?

SELWYN RAAB: Well, one major reason was that J. Edgar Hoover didn't want the FBI to do anything with the mob. They didn't do anything until after his death in 1972.

I started as a reporter in New York in the 1960s on the education beat. I was working for a year when there was a big scandal: schools were falling apart. I was assigned to the story and found so many connections. There were secret Mafia partners to all these construction firms that were allowing ceilings to collapse, and building shoddy buildings. There was a big investigation, and eventually the city got rid of some of the people who worked for the Board of Education and banned some of the contractors. But they never went after the Mafia.

So I started asking around: Why don't you do anything about the Mafia? "It's too hard," I was told. But the real reason was that the Mafia was paying off the politicians and the judges. Every stone you turned up in this town had to do with the Mafia. Garbage, the fish market, you name it.

Also, when you talked to mayors off the record they'd say: 'everything runs smoothly now. If you fool around with the construction industry, there will be a strike. If you do anything about trying to regulate the garbage industry, they won't pick up the garbage. If you try to do anything about the fish market, restaurants won't get any fish. Leave well enough alone. They're not bothering anybody.'

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Can you point to any industries that the Mafia ruined or ran out of town?

SELWYN RAAB: I used to speak to people in the garment center, and they said you had a choice: either you get protection from the mob, or you sign up with the union and pay the union dues. The union will let you be non-union, but you have to be hooked up with some family. In fact, the corrupt unions were getting part of the payoffs.

There were mob families running all the trucking in the garment center – the Colombos and the Luccheses. You couldn't be an independent trucker and go into the garment center. You'd have flat tires, and your drivers would be beaten up. These weren't the only reasons – there were runaway industries for cheaper labor elsewhere, too– but they added an extra inducement. Why bother?

It wasn't just the garment industry. Garbage haulers wouldn't come into New York because they knew it wasn't worth the effort. If you came in you'd be shaken down, and if you didn't pay them off there would be a strike, because they controlled the Teamsters on the garbage locals.

A lot of fish wholesalers wouldn't come into New York for many years. They would rather go to New England, or the big fish markets in Baltimore, where they wouldn't have this trouble.

PHILIP ANGELL: And the important thing to remember is that it was underwritten by violence, no matter what industry.

ROMANTICIZING THE MOB

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Why do people have such a romantic view of this?

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Why do people have such a romantic view of this?

SELWYN RAAB: Well, that's Hollywood. American entertainers have always had a vicarious love affair with criminals. They're interesting people; you're more interested in rogues than good guys. Do you want to do a story about the founder of the Red Cross or Salvation Army? No one is too interested in that.

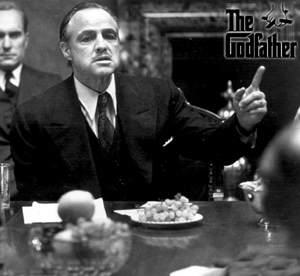

One of my pet peeves is a movie like the Godfather, where we set up the idea that there are good Mafiosi and bad Mafiosi. Don Vito Corleone, played by Marlon Brando, he's a white hat, a good guy cowboy. At one point, he's opposed to narcotics, and as a result there's an attempt on his life by the bad Mafiosi. But who wins? The good guys.

They try to create this image that it's not so simple, that you can identify with them.

I don't watch the Sopranos every week, but when I do watch what I see is a soap opera not about a mob family, but a dysfunctional suburban family. If you're a middle-aged man, you can easily identify with Tony Soprano. His kids are rebelling against him, his wife is smarter than him and wants to leave him, he doesn't have the old time loyalty when he goes to the office anymore. He has all these midlife crises, even though he lives in a mini mansion, has a harem of beauties throwing themselves at him, and he's got big cars and all the money in the world. Yet he's got these crises; you can sympathize with him. You don’t see him for the most part killing people.

You get a vicarious kick out of watching these people. Look at the great lives they lead: they sleep late, they don't have to go to work, they make a lot of money, they have a lot of woman friends. It looks good.

There's one other aspect which I think is a subtext to all of this, which makes these movies popular and is why people romanticize the Mafia: they're antiestablishment. In the Godfather, they talk about how the Italian Americans couldn't get a break. They had to become a government onto themselves, because the WASP establishment wouldn't allow them to become bankers or big businessmen. You can see it also in the Sopranos. His father was a laborer. What a choice: drive a truck for a living, or could he work for the mob and make a lot of money, be comfortable, take care of your family?

GOTHAM GAZETTE: But how much of that is true?

SELWYN RAAB: Well, I've talked to a few made men. They always rationalized what they did and why they did it. But they have always been into anything that will bring them money.

Â

Mayor's Summit On Illegal Guns

What is a city to do? There are illegal guns on the street that are being used to commit violent crimes, so as a city you do what you can on your own:

- step up enforcement of gun possession laws

- intercept illegal sales

- lobby for tougher laws and stiffer penalties in the state legislature

- and even try suing gun manufacturers and dealers for negligent marketing techniques.

But most of the guns -- reportedly 92 percent of those recovered between 1988 and 2003 -- are from out of state. So no matter how many guns you take off the street here, more keep coming. Other states have lax gun laws, so it is easy for people to buy guns there and bring them to your city, and your laws have no effect outside of your borders. And the people that are supposed to intervene when there are problems across state lines in a federal system -- Congress and the rest of the national government -- do nothing; indeed they are trying to prevent you from obtaining the information about where the guns are coming from .

So what's a city to do? If you are New York City, you call together mayors from 15 cities from around the country at Gracie Mansion. On April 25th, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and co-host Mayor Thomas Menino of Boston, played host to what was dubbed the Mayor’s Summit on Illegal Guns. Half photo op, half strategy session, the meeting concluded with the attendees signing a "statement of principles" (in .pdf format) which called for increased punishment of illegal gun possession and trafficking, action against gun dealers who allow so-called “straw purchases” (the use of a third party to buy guns), and resistance to federal efforts to limit the cities’ access to gun trace information.

While it is true that shootings are down in New York so far this year, in many ways Bloomberg has staked his second term on making tangible progress in his campaign against illegal guns. He made the issue a central plank in his State of the City address, traveled to Washington to testify before Congress, and now has attempted to put together a broad coalition of local politicians from across the country. If nothing else, the effort has made Bloomberg a nationally-recognized name.

Positive Reaction, But Fruitful Follow-up?

The reaction in the local press has been positive. The Journal News (Westchester) issued "cheers for leaders demanding action”. The Post made light of the fact that Bloomberg declined a request from the National Shooting Sports Foundation to speak at the meeting.

Of course, the important question is whether the mayor’s coalition-building will do any good. Barring a major change in this fall’s federal elections (not out of the question, but certainly not a sure thing either), Congress is unlikely to take any action to tighten federal gun laws. And given recent attempts to restrict access of local governments to gun trace data, New Yorkers might be forgiven for believing that Congress wishes them ill.

Congress aside, there are two ways that the “Mayor’s Summit” could prove fruitful. Politically, the city can only benefit from attempts to reframe the debate over guns and from the creation of a broad network of like-minded mayors. The group of 15 that attended the meeting at Gracie Mansion included the mayors of such cities as Milwaukee, Jackson, Mississippi, Dallas, and Tulsa. A quick look at the press reports of the summit and the obligatory “balance” quotes from the National Rifle Association give a hint as to the anti-Bloomberg talking points: The mayor is an elitist with an elitist plan, out to get law-abiding gun owners. To the extent that the coalition grows to include more politicians from cities like Jackson, Dallas, and Tulsa -- hardly bastions of northeast-style liberalism -- the group’s ideas may have more currency.

Practically, if this group proves to be more than a one-time photo opportunity, and can expand to include a broader network of cities, there are real opportunities for mutual assistance. Bloomberg has made much of his fondness for technology and information sharing, not only in public safety initiatives but throughout city government. Figuring out a way to share information about gun trafficking and related problems with cities across the country can only benefit New York’s efforts (and everyone else’s as well). Sometimes when Congress refuses to act, the people affected on the local level just need to get creative.

Court Victory

As if on cue, the same week of the Mayor’s Summit, a federal judge in Brooklyn handed the city another victory in its lawsuit against gun manufacturers and dealers . Judge Jack Weinstein, a Lyndon Johnson appointee who is a Senior Judge in the Eastern District of New York, again allowed the city’s suit to go forward, despite apparent federal law to the contrary. Last year, Weinstein held that the suit could continue, despite the passage of a law prohibiting such suits (that decision is currently pending on appeal in the Second Circuit). And now Judge Weinstein has held that Congress’ recent attempts to restrict the use of gun trace data by local governments do not apply to the New York case, because the city had possession of the information prior to the passage of the law. It is unclear whether Judge Weinstein’s decision will hold up on appeal, but for now at least the city’s lawsuit is still alive.

David Dean, a student at New York University School of Law, worked as a policy analyst in the Mayor's Office of the Criminal Justice Coordinator.Â

Injured, Undocumented -- And Legally Protected

Gorgonio Balbuena, who was born in Mexico, said he was injured when he fell from a ramp while pushing a wheelbarrow on a construction site in the city. Satnislaw Majlinger, who was born in Poland, said he too was injured when he fell while working on a different construction site in the city.

Both said their injuries are severe. Both sued, claiming labor law violations.

And neither had legal standing to work, or even live, in the United States.

Two different state appellate courts — one in Manhattan, one in Brooklyn — delivered two contradictory rulings on their rights to sue for lost wages.

The Appellate Division covering Manhattan and the Bronx reached the conclusion that damages such an injured worker can claim are limited to "the wages [he] would have been able to earn in his home country." But the Appellate Division that hears cases from the city's other boroughs, as well as Long Island and Westchester, reached a contrary result - - concluding that all workers, regardless of immigration status, are protected by the laws of this state.

The highest court in New York State, the New York Court of Appeals in Albany, has now resolved these contradictory decisions by upholding the one from Brooklyn. The court declared that construction workers injured on the job can seek damages for past and future loss of employment and income, even if they are "aliens," immigrants with no documents allowing them to work in this country.

Judge Victoria A. Graffeo of the state's highest court, wrote the combined opinion in Gorgonio Balbuena v. IDR Realty and Stanislaw Majlinger v. Cassino Contracting Corp., holding that both Balbuena and Majlinger could sue for lost wages.

The Manhattan judges were wrong, the Albany judges decided, to rule on the basis of a federal case known as Hoffman Plastics v. Natoinal Labor Relations Board, because the immigrant worker's conduct in the Hoffman case was unlawful (he used fraudulent documents to get hired). But, while both Gorgonio Balbuena and Stanislaw Majlinger were in the United States illegally, their conduct on the job was not illegal. Since it is illegal for an employer to hire employees without verifying authorization to work in this country, it is the employer who acts unlawfully by hiring an undocumented worker. No crime is committed by an "unauthorized alien" employee who takes the job, unless fraudulent documents were used, which neither Balbuena nor Majlinger did.

Ultimately, Judge Graffeo wrote, "the question is whether an award of past and future wages to an undocumented alien worker undermines the objectives of federal immigration law."

While defendants claimed that permitting an undocumented alien to recover lost wages is "in contravention of the purposes and objectives of federal immigration law, condones past transgressions and encourages future violations," plaintiffs, joined by Attorney General Elliot Spitzer, argued to the contrary. The plaintiffs' position was that an undocumented alien should be allowed to recover for monies lost as a result of defendants' failure to adhere to the work place safety requirements. They also argued that precluding lost wages would make it more financially attractive for noncompliant employers to hire illegal aliens, thereby undercutting the central goal of the federal act, and providing less of an incentive for employers to meet state labor requirements regulating occupational health and safety.

"It was the New York legislature's intent to achieve the purpose of protecting workers by placing 'ultimate responsibility for safety practices at building construction jobs where such responsibility actually belongs, on the owner and general contractor,' instead of on workers, who are scarcely in a position to protect themselves from accident," the Court held. "The Labor Law," the opinion said, "applies to all workers in qualifying employment situations - - regardless of immigration status - - and nothing . . . negates the universal applicability of this principle."

According to the 25 page opinion, "limiting a lost wages claim by an injured undocumented alien would lessen an employer's incentive to comply with the Labor Law and supply all of its workers the safe workplace that the Legislature demands.

"An absolute bar to recovery of lost wages by an undocumented worker would lessen the unscrupulous employer's potential liability to its alien workers and make it more financially attractive to hire undocumented aliens." The majority opinion, from which two judges dissented, said, "illegal aliens are willing to work in jobs that are more dangerous and undesirable - - and for less money - - than their legal immigrant and citizen counterparts, [and] would actually increase employment levels of undocumented aliens, not decrease it as Congress sought."

The cases can now proceed to trial where evidence may be introduced by an undocumented alien, about work history and prospects, just as in any other personal injury case. But the jury would be entitled to hear about the likelihood of future earnings in this country, including immigration status.

Eventually the issue might reach the Supreme Court of the United States which would be faced with New York's conclusion that "an undocumented alien performing construction work is not an outlaw engaged in illegal activity."

Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court Justice