When Henry Weinstein bought a commercial building at 752 Pacific St. in Brooklyn 1985 he never expected that 20 years later the government would want to take it away and give it to a developer. Weinstein said that he would be shocked if his land was being taken for a hospital, a bridge or a library. But seeing it seized to make way for Forest City Ratner's Atlantic Yards project shakes his faith in the government. "This is the most un-American thing I have ever experienced," he said.

As New York City has reshaped itself over the past decade, the government has given private developers, such as Forest City Ratner, a powerful tool -- an eminent domain law that allows them to seize land from other property owners. Now some politicians believe the law needs change to protect property owners, such as Weinstein.

Assemblyman Richard Brodsky has put together a package of legislation that would create a commission to review the state's eminent domain process, give land owners fair compensation for their property and establish an ombudsman who would help land owners whose property is targeted by eminent domain. Later this week Sen. Bill Perkins will unveil legislation that he says would change the state's eminent domain laws to better protect property owners. The situation in the legislature, along with a recent appellate court ruling that found the process the state used to take land for a Columbia University satellite campus in upper Manhattan was unconstitutional, could result in the first major changes to New York's eminent domain laws in more than 30 years.

The possibility that the state might finally redo its eminent domain laws -- laws that have remained the same as other states updated theirs -- has caught the interest of civil rights lawyers, property owners and advocates. But developers, real estate interests and some politicians fear changes could make it more difficult for the state to improve blighted neighborhoods in desperate need of investment, infrastructure and jobs.

"Eminent domain is an essential governmental tool that allows for the implementation of important development projects to the benefit of the public at large," Lisa Willner, public affairs manager for Empire State Development Corp., which oversees the state's eminent domain process, said in a statement.

As the legislature considers the law, Weinstein is fighting the taking of his land in court. He acknowledges his legal battle may be futile. "The Empire State Development Corp. rules as kings. We left England to get away from it, but they have the power of a sovereign," he said.

Defining Blight

The state can seize property it determines to be blighted. While the state generally heads up eminent domain projects, in some instances, such as the Atlantic Yards case, the developer's advocacy leads to the state's involvement.

State law defines blight as "substandard and insanitary." Land that is determined to be blighted can be given by the state to another private owner for the purpose of economic development. The state can also use blight determination to make way for public works projects such as roads.

According to attorney Michael Rikon, who represents property owners in the Willet's Point section of Queens, where the city is planning a major redevelopment, the term is so vague that the contractors used by the government basically make up formulas as they go along. "The definition of blight is so broad it could come down to cracks in the sidewalk. Even the mayor's townhouse could be blighted, because it only supports one family," he said.

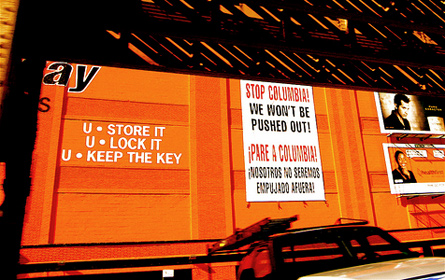

Civil rights attorney Norman Siegel, who represents Tuck-It-Away, a storage company that is fighting Columbia University's expansion plans, agrees. "Basically they are saying if there is a Motel 8 and Hilton comes along and says they can make the property more valuable, then it [the Motel 8] can be declared blighted." Many advocates, Siegel said, have begun saying the land in these cases should not be labeled "blighted," but "coveted."

Siegel calls eminent domain one of the premier civil rights issues of this century. "I really think it is the civil rights issue of the 21st century. It disproportionately impacts poor neighborhoods and people of color. It cuts across partisan lines," he said.

The Eyes of the Beholder

Of further concern to Rikon, Siegel and others is who makes the call. While the board of the Empire State Development Corp. technically determines whether a property is blighted, the agency hires a contractor who is paid millions of dollars to conduct the technical study and write a report. In the case of Columbia's campus expansion, the university and the development corporation used the same contractor, AKRF, at the same time. In the case of Atlantic Yards, AKRF worked for the developer, Forrest City Ratner, and then for the ESDC.

In his ruling against Columbia, Justice James Catterson described AKRF's study of land for the Columbia University project as "idiocy." Saying that the report cites such easily reparable problems as "unpainted block walls" and "loose awning supports" as blight, Catterson wrote in his majority decision, "We questioned [AKRF's] ability to provide 'objective advice' to the ESDC, particularly with respect to its preparation of the blight study."

Advocates say that the ESDC does not have to use AKRF as there are other qualified firms that do the same work. "Our judgment is that AKRF is the most qualified to do this work," a spokesperson for the ESDC told the New York Times.

For the Empire State Development Corp. to use evidence supplied by someone working for the contractor "seems like collusion. It doesn't seem fair, and sometimes perception is more important than fact. The entire process seems blighted," said Perkins.

AKRF defended its conduct. "As a firm of planners and analysts, AKRF's responsibility is the collection and assessment of data in an objective and thorough manner," a spokesman for the firm said. '"Any suggestion that the firm -- widely recognized as a trusted industry leader -- would compromise the quality of its work is incorrect."

"We need a more discrete definition of what is blight, not paid consultants who decide for themselves," said Michael Rikon, the Willet’s Point attorney. Rikon said landowners who have been through the process tell him. 'On the form for blight that consultants use there is one box for blighted and they check it.'" The process is much more complicated than checking a box. But critics say the formulas used almost always lead to the same conclusion -- and it's one that favors developers.

Changing the Process

According to Siegel, property owners only get one, very narrow chance to argue that their property should not be taken away from them. He said landowners in other states have more of an opportunity to challenge decisions. "As far as I can tell New York is the only state where you start at the appeals level," Siegel said. "You get 15 minutes to argue. There is no cross-examination. I think it is a violation of due process."

Perkins and Brodsky hope to address that issue in their legislation.

Brodsky has been working to change the eminent domain law for 10 years. "I don't think eminent domain should be stopped as a useful tool for the public good but with this pattern of private to private transfers I think the current laws may be inadequate. We need schools hospitals and libraries, but person-to-person transfer is an entirely different animal," he said.

One of Brodsky's bills would establish an eminent domain ombudsman "so that normal citizens are not overwhelmed." Brodsky also would like to see owners who lose their land in the eminent domain process be compensated 150 percent of the value of their property. "Anyone forced to hand over their property should share in the profits," said Brodsky. And Brodsky would create a process to review developer's plans to make sure the surrounding community would benefit. He also would create commission to review the scope and effectiveness of current laws, and would like to get rid of the finding of blight all together.

Perkins' bill is said to contain a provision that would change the definition of blight from substandard and insanitary to something more measureable, though what the new standard would be is not yet clear. The senator also would like to include a mechanism to ensure that developers follow up on their promise to the community and to review exactly what benefits the community can expect to enjoy from any project benefited by eminent domain.

The bill contains other tweaks, not yet announced, as well. Perkins says he expects bipartisan support in the Senate as well as help from the Assembly.

Amy Lavine, a staff attorney at the Albany Law School’s Government Law Center who helped Perkins put together his legislation, said it is not intended to disrupt the eminent domain process. "The definition of blight as it stands is very vague. We want to change that. The law increases transparency and accountability in the process. We are not interested in disrupting the process. We just want to make it better." Lavine said.

Thwarted Efforts

Change for New York's eminent domain process has been a long time coming. Over the years, legislators from both parties and both houses have tried in vain to make changes to the law to better protect private property owners only to find their efforts blocked by real estate interests.

In 1974, Rikon took part in a committee charged with making changes to the eminent domain process. "The last time New York changed the law was '77," said Rikon. "What happened was, when we got to the final version the city's lawyers and city corporation counsel eliminated a lot of provisions that they were against. That was 33 years ago. We really need to revise everything step by step."

Most states changed the process and the standards for applying eminent domain following a Supreme Court ruling in 2005. In Kelo v. City of New London [Connecticut], the court decided that a state can take property from a private owner and transfer it to another owner for the sake of economic development. Forty-three states then changed their laws to protect property owners. New York did not.

"Kelo caused a firestorm around eminent domain because people thought eminent domain could only be used for government projects. Kelo said that's not true. It can now be used for public betterment," said Siegel.

In 2009, four years after the monumental Kelo decision, the case was in the news again. The developer that was the beneficiary of the Supreme Court's decision pulled outof the city, and now New London has been left with barren lots.

After 30 years, some observers think Perkins will be able to seize upon public sentiment in an election year and force drastic changes in the law. Brodsky said it would be about time. ""I have been at this for 10 years. I did not jump in after Kelo. It would have been a good time to do this three years ago," he said.

"It could become a firestorm if Bill pushes the issue and more people join in. Folks are angry at politicians. This will be a ripe issue. I think Perkins is sensing that. I know it is certainty ripe with us and with our clients," said Siegel.

On the other side, the real estate industry and other businesses will likely work to preserve much of the state's eminent domain law. They proved this in 2005 in the wake of the Supreme Court's Kelo decision.

"We are alarmed," Kathryn Wylde, president of Partnership for New York, told the state Assembly in 2005, when legislation to alter eminent domain law was being considered. "Without the power to condemn private sites to support economic development projects, New York and other older urban centers could not have kept pace with demands for upgraded infrastructure, modern office facilities and an expanded housing stock."

Serious opposition to changing the process could very well come from Mayor Michael Bloomberg. Advocates say the mayor's office has lobbied hard against such changes in the past. Recently in a New York Times article on the subject of eminent domain reform, Lisa Bova-Hiatt, a deputy chief at the New York City Law Department, said the city would not be opposed to "thoughtful change" but would oppose "ill considered action" sparked by hysteria.

Perkins right now is taking that as a good sign. "We welcome the mayor's help," he said, "I think it would be very valuable."

The governor could represent another obstacle. Following the decision by the appellate court that halted the Columbia expansion, Perkins called on Gov. David Paterson not to appeal the decision. He also asked the governor to institute a moratorium on eminent domain. "I remember standing with the Senate minority leader, now Gov. David Paterson, on the steps of city hall when the Kelo decision was announced. David was very concerned about the use of eminent domain back then," said Perkins.

Five years later, Paterson declined to heed Perkins' request, but Perkins hopes Paterson might still be convinced to join his cause.

Whatever the governor does, Perkins said he thinks the public is on his side. "I'm optimistic the public at this time is calling for reform. They want more reform," he said.