As national economic conditions continue to worsen, threatening federal and state budgets, prospects for balancing next year's city budget remain surprisingly upbeat. Neither the mayor nor the City Council seems inclined to fight over proposed budget cutbacks or tax decreases.

But some of the negative consequences from Mayor Michael Bloomberg's January financial plan, also known as the preliminary budget, are becoming clear. The Independent Budget Office's March analysis of the January plan and the New York City Council's recent response to it lay out both its immediate good and bad news. At the same time, the council's detailed proposal for a "rainy day fund" shows how the January plan fails to deal with the city's long-term budget problems.

The good news stems, first, from budget office and council projections that the January plan underestimated tax revenues for this fiscal year (2008) and next. The IBO estimates tax revenues this year to be $777 million higher than the mayor projected and $752 million higher in 2009. While not that optimistic, the council still projects higher tax revenues than the mayor -- $258 million this year and $392 million next. The council also has identified other revenues and savings that could provide a total of almost $1.4 billion in new resources.

The higher revenues, plus the use of big budget surpluses from previous years, means budget-balancing this year and next should not be too difficult. In fact, the council is comfortable enough with fiscal prospects to support both the mayor's retention in 2009 of this year's 7 percent cut in property tax and the $400 residential owner property tax rebate -- even though this will cost over $1.3 billion in lost revenues.

But the bad news is two-fold. First, the January plan includes some big service cuts and represents a rather dramatic reversal in such mayoral priority areas as public education, homeless services and libraries. Second, the January plan dodges the longer-term fiscal problems -- the annual deficits of $5 billion to $6 billion or more projected for 2011 and 2012 -- gaps a new mayor and a new council will face.

Across-the-Board Budget Cutting

The bulk of the mayor's budget-balancing for this year and next comes down to across-the-board cuts, 2.5 percent this year, and 5 percent next year. (The mayor's budget director suggested at a recent council hearing that Bloomberg might seek an additional 3 percent across-the-board cut for 2009.) The IBO report has an excellent rundown of what the first round of these cuts means.

In public education -- the mayor's biggest priority -- the plan cuts $180 million in the current fiscal year. Some 63 percent of that will come from individual school budgets. The impact on schools ranges from $10,000 to $447,000 per school, and averages $72,000 per school in 2008. The plan for next year is to cut $324 million, 69 percent of which will come from the schools.

The mayor could have difficulty implementing his cut in another priority area: homeless services. The city's efforts have been disappointing and, as a result, the cost of providing shelter to families has exceeded estimates. In the five years beginning June 2004, the city aimed to reduce the number of homeless families by two thirds. However, according to the IBO, the number of homeless families actually rose by 18 percent from a low in December 2005 to January 2008.

The cost of sheltering these families, projected at $314 million last June, had to be increased by $86 million in January. Although the family shelter population remains at the January level, next year's projected family-shelter costs are again $314 million. (The single adult shelter population reflects better news; it has decreased 23 percent from a high of 8,783 in January 2005 to 6,762 in August 2007.)

In both education and homeless services, the mayor has, more than mid-way through his tenure, shifted policies and administration in major ways not cited in the financial plan, or in the most recent preliminary Mayor's Management Report.

In education, regional administration has been abandoned, leading, the IBO reports, to the elimination of 472 jobs. Much decision-making has shifted to principals; new funding formulas for schools are supposed to give more dollars to more needy schools. The IBO also notes, that recent additional state education funding has been tied to new accountability requirements that the city must meet, such as class size reduction and expansion of pre-kindergarten classes.

In homeless services there are big shifts also, with services for single adults being re-structured and a new rental assistance program created with new rules and expectations. The IBO report is a first step in understanding and monitoring those shifts.

The Council Response: Cuts, Transparency and Reserves

Overall, the council supports the mayor's budget plan. Even in the face of more than $500 million in education cuts over 18 months, the council does not object to the level of cuts but only to their targets. Instead of some of the individual school cuts, the council would reduce the department's $3.17 billion in contracts with outside vendors in 2009, almost 9 percent higher than 2008's total. Bus contracts, for example, are going up over 11 percent a year, and the council urges rebidding of those transportation contracts. Overall, the council proposes a 4 percent across-the-board cut in education department contracts, saving $127 million next year.

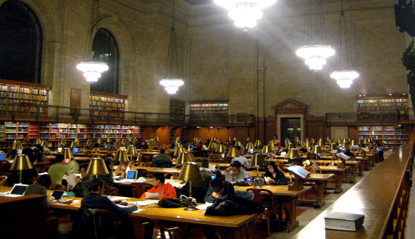

The response does include some mild criticism of the mayor's breaking an agreement with the council to minimize friction over repeated over the mayor's repeatedly removing funding for council priority programs, knowing full well the council would restore that funding. The idea was to avoid the annual "budget dance," in which the council each year fights to re-fund favorite programs. Nevertheless, Bloomberg seems to have revived the dance. The council fears, for example, that the mayor will eliminate as much as 60 percent of the funding for six-day library services that was part of the June 2007 agreement.

What may, unfortunately, get lost in the council response is its most detailed and interesting proposal yet to create a rainy day fund, a key to preventing future budget crises. The developing flap uncovered by the New York Post last week over the council's use of non-existent organizations to hide internal budget reserve accounts is (at best) an embarrassment. It would be a shame if the revelations overshadow a fundamental question the council has had the courage to raise: how to create a reserve fund (a rainy day fund) that would become part of the regular budget process, stabilize long-term planning, and make the use of budget surpluses more transparent.

As part of its argument for the new fund, the council has a useful new analysis of recent budget-balancing and how the current use of "rollover surpluses" can distort the city's fiscal condition. Every year since 1981, the city has ended the budget year with a balanced budget as required by state law. Often, though, it has only accomplished this through the use of a previous year surplus to pay for current-year expenses.

If we look simply at current-year revenues and current-year expenditures alone (i.e., "the operating budget"), in 10 of the last 27 years the city spent more than it brought in during the fiscal year, averaging operating deficits of more than $2.6 billion a year. In 17 years there were operating surpluses, some exceeding $4 billion. What the council proposes is a state-legislated reserve fund - a "rainy day fund" - where surplus funds would be put away in good times and from which funds could be drawn in bad times.

When economic conditions improve, the council proposes the city implement a reserve fund that would "equal 12.5 percent of expenditures, thus providing a cushion for the inevitable next cyclical downturn in the city's economy." That would mean a reserve fund of about, say, $7.5 billion with a $60 billion budget, roughly what the 2009 budget will be. The council sees such a fund as giving it an equal role with the mayor in using annual surpluses: "Establishing such a fund would bring these reserves into the regular budget process and result in greater transparency," the budget response states.

The rainy day fund proposal deserves action as well as discussion. Unfortunately, action is unlikely this year. The IBO and council analyses of the mayor's financial plan suggest that both the mayor and council are anxious to keep things simple this year. New tax revenues, across-the-board spending cuts and holding on to tax cuts may well make for a relatively easy budget. The big problem, however, is that there is no commitment by either the mayor or the council to a long-term strategy for budget stability.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â