|

|

After years of volunteering in her school in Astoria, Anita O'Brien now gets paid to be a school activist. As one of the 1,200 new parent coordinators, parents approach her at school, at meetings and in the neighborhood -- hungry for information and guidance. "They feel very comfortable coming up to me and asking me questions and I always try to get them an answer," the mother of three says.

But for all their efforts, O'Brien and the others do not always have the information. After a year of major changes in New York City schools, many questions remain unanswered.

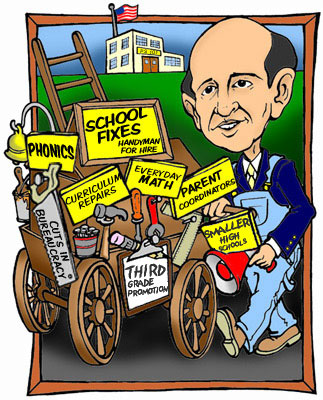

The biggest one for most New Yorkers: Has the Children First Initiative – which brought the virtual elimination of community school districts, personnel changes, the introduction of a standardized curriculum and a new third grade promotion policy - improved New York's schools?

"Not to sugarcoat this [but] I think that it was by and large an extraordinary year for us," Schools Chancellor Joel Klein said in an interview. "We've executed well -- not perfectly, but well -- and I think we're positioning the system for the long-term transformational change."

"If reading and math scores aren't significantly better, I will look in the mirror and say I've failed," Mayor Michael Bloomberg was quoted as saying when he won control of the school system two years ago. "And I've never failed at anything in my life."

And so far, the mayor sees success here as well. At a press conference last week to trumpet improvements in school safety, he offered a generally upbeat assessment of the year. "The fact of the matter is, we don't have broken windows and missing floor tiles," he said. "The fact of the matter is we do deliver the books on time. The fact of the matter is we have parent coordinators that in most cases are making a very big difference."

But others disagree. At a press conference in late June, Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum gave the chancellor a grade of C-, saying his "ambitions have not so far produced positive results." In particular, she faulted the mayor for not doing more to relieve crowding in classrooms and for not seeking advice from parents, teachers and principals.

The City Council, whose speaker Gifford Miller is likely to challenge Bloomberg next year, has been a persistent critic, taking on many of the individual reforms. For example, it has condemned the mayor's policy of holding back third graders who fail a standardized test, questioned the drive toward smaller high schools and criticized the department's capital budget.

The teachers union, which is locked in a contentious contract dispute with the city, has faulted Klein and his top assistants for ignoring the expertise of teachers and interfering too much in the classroom.

Here is some of what Bloomberg and Klein tried to do this year and how they fared.

- CURRICULUM

- TEST SCORES

- THIRD GRADE PROMOTION

- BREAKING UP HIGH SCHOOLS

- HIGH SCHOOL ADMISSIONS

- REORGANIZATION

- THE TWEED CULTURE

CURRICULUM

Until September, New York had no uniform education program for its 1.1 million students. Individual community school districts -- and schools -- selected their programs, often changing them from year to year. This confused students and placed a particular burden on low-income youngsters who tend to switch schools more frequently than their more affluent classmates.

In 2003, Klein said that, except for some 200 high performing schools, all schools would adopt uniform curricula for reading and math.

Some educators -- notably the teachers union -- objected. Opponents grumbled that the Department of Education was dictating what teachers could hang on bulletin boards and how they must arrange the desks. Jill Levy, president of the Council of School Supervisors and Administrators, which represents principals, said this was such extreme micromanaging that she termed it "nanomanaging."

"Not everyone learns at the same pace," said Jo Rossicone, outgoing principal of Brooklyn's IS 220, whose student body includes many English language learners. "They don't take into account language challenges." But despite that, Rossicone believes the uniform curricula are a good thing: "I see a focus. I see everyone on the same page," she said.

If liberal educators had their doubts about a uniform curriculum, conservatives objected to the specific programs selected. Bucking what Education Week has described as "a national penchant for a highly structured, skills based approach to reading and mathematics instruction," the Department of Education spurned phonics and math drills. The language curriculum does not stress letter sounds but instead employs popular children's books, literary discussions and writing. The math curriculum is similarly non-traditional.

This approach encountered flack from the U.S. Department of Education, which expressed doubt that the reading curriculum for the youngest students would enable the city to qualify for about $40 million in federal funds. In response, Klein adopted a more traditional commercial reading program for 49 of the city's lowest performing schools.

This did not mollify critics such as Sol Stern of the Manhattan Institute. "Many of the programs and methods now being crammed down teachers' throat have no record of success and are particularly ill-suited for disadvantaged minority children," Stern wrote in City Journal last fall.

School officials, of course, disagree. "We did not want to settle for anything but a rich and vigorous curriculum for our students" said Diana Lam, the deputy chancellor who selected the programs before being forced to resign in the nepotism scandal earlier this year.

THE TEST SCORES

Whatever the shortcomings of standardized tests, they have become a kind of shorthand for determining whether what is being done in the classroom works. This year's results produced a mixed verdict.

For the first time since the test was instituted six years ago, fourth grade reading tests scores fell in the city, as more than half the children tested failed to meet state standards. On the other hand, eighth grade scores improved, as did math scores for third, sixth and seventh graders.

While saying a single year's test scores "are not what this is about," Klein said, "It's a favorable picture." Scores rose on six of the tests given, he said, and fell on three.

The mayor's opponents saw things differently. Citing the fourth grade reading scores, Speaker Gifford Miller called upon the Department of Education to consider scrapping the new reading program. And, while math scores rose, opponents of the new curriculum attributed it more to test preparation than to the new approach to teaching mathematics.

THIRD GRADE PROMOTION

Parents, teachers and New York employers have long despaired at the number of students who leave the school system without basic skills. How could a student be promoted year after year and be unable to understand written material or do basic math?

To confront this, in January. Bloomberg announced that he would end what he called "social promotion" for third graders, leaving back children who received the lowest score - a level one out of a possible four -- on standardized reading and math tests.

As third graders crammed for the exams, many educators declared the policy put too much weight on a single test. Others said efforts should instead focus on improving education in lowest grades, by reducing class size. "They are taking no responsibility for how a kid can be in schools for four years and still not know how to read well," said John Beam, executive director of the National Center for Schools and Communities at Fordham University. Klein now says the schools will try to shift more resources to helping their youngest students next year.

The department allowed some exceptions to the policy, giving students a chance to attend summer school and try again, instituting an appeals process and exempting English language learners and special education students. But the opposition persisted until the day the Panel for Educational Policy, the largely toothless successor to the Board of Education, was set to vote on the plan. With his proposal facing defeat, the mayor arranged for the firing of three members of the panel, insuring that his third grade retention plan would be a reality.

And so more than 10,000 of the city's approximately 80,000 third graders now face summer school or repeating third grade -- up from 4,817 third graders left back in June 2003.

The true test of the policy will come as these children move through the school system. Proponents say it will help insure that students do not reach high school unable to read well or do math. "If people tell you that social promotion is not an issue in our school system than they just haven't been in our high schools, " Klein said. Thousands and thousands of kids who are basically not reading and not doing elementary math -- that seems to me to be the current crisis in public education."

But many educators argue that retention will not solve that problem. A paper by the Institute for Education and Social Policy at NYU's Steinhardt School of Education and the Center for Schools and Communities reviewed the findings on retention and concluded that students who are left back do not score better on standardized tests later on but instead are more likely to drop out of schools than other students. New York City has adopted such policies in the past only to drop them several years later.

Whatever the educational effects, the mayor seems to have reaped political benefits from the controversy. A poll found that New Yorkers backed the mayor's policy by a two-to-one margin.

BREAKING UP THE HIGH SCHOOLS

While New York boasts some of the nation's top high schools, it also has many high schools where most students fail to meet basic standards for graduation. At Theodore Roosevelt High School in the Bronx, for example, only 15 percent of students passed the required English Regents test.

To address the problem, the Department Education has begun breaking up large struggling high schools into smaller schools. Roosevelt High School is being phased out, to be replaced by four schools. Brooklyn's Erasmus Hall High School, a distinguished school that had fallen on hard times, is now three high schools. Altogether the city opened 42 small high schools last September and expects to open 41 more high schools as well as 15 small combined junior/senior high schools in September.

This is part of a national trend fueled by money from the federal government's Smaller Learning Communities Program and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which has given New York $79 million to promote small schools.

But now signs are emerging of a small schools backlash. Critics argue that the schools do not always deliver on their promise. The City Council education committee reported that students in small schools do not perform as well on Regents tests as similar students at regular schools.

As might be expected in New York, school officials must struggle to find places to put the new schools. They often squeeze the new programs into already crowded schools making the congestion worse. Staff and students at the old, big school then complain the new school gets preferential treatment.

HIGH SCHOOL ADMISSIONS

With such great disparities between the ciyt's good high schools and bad ones, the high school application process resembles a winner take all lottery. This year, the Department of Education revamped the procedure, modeling it on the application process for medical residency programs. Students listed up to 12 schools in order of preference and were matched with the school highest on their list that would accept them. But unlike in previous years, students were no longer automatically admitted to their local -- or "zoned -- high school.

At the end of the initial application round, some 14,000 students had not been admitted to any of the schools on their list. The Department of Education provided them with lists of schools that still had openings, many of them new schools or low-performing ones.

Observers chalked the problem up to the general shortage of decent high schools in the city. But in June it was discovered that the new policy had left some seats at top high schools unfilled. This outraged parents whose children narrowly missed acceptance.

Klein insisted the process still represented an improvement over the scramble in previous years, but Miller called for the education department to come up with a new way to match students and schools.

REORGANIZATION

As Bloomberg focused on education, he took aim at a bureaucracy, which, he repeatedly charged, was more interested in protecting its own than educating young people. To shake up that structure, Bloomberg and Klein all but eliminated the 32 community school districts, replacing them with 10 instructional divisions. The city sold the old school headquarters at 110 Livingston Street in downtown Brooklyn and moved a pared down bureaucracy to the Tweed courthouse next door to City Hall.

But the new organization and the turmoil created some problems. Some critics say the department has lost institutional memory and expertise. According to Levy, principals between ages 55 and 60 are leaving in unprecedented numbers. The New York Sun reported that as many as a third of the 113 new local instructional superintendents that Klein hired last year are quitting, frustrated by the demands of the job.

Some operations got lost in the organizational shuffle. The education department eliminated the bureaucracy that reviewed student suspensions, creating a huge backlog in the disciplinary process. This, more than any increase in school crime, gave rise to last winter's school security crisis.

Similar problems plagued special education, which Klein also reorganized. By last winter the New York Times and the public advocate's office reported the system was in disarray, with students languishing in inappropriate settings while awaiting evaluation. Klein has since announced steps to address the problem.

But the confusion went beyond those two programs. Administrators at a leading Manhattan high school told parents last fall that they really did not know who in the Department of Education was responsible for the school.

"With the old Board of Education, people were downright nasty," recalled Brooklyn parent Carmen Colon. "Now they smile and can't help you."

The parent coordinator program was instituted partly to help parents negotiate the bureaucracy, and many consider it a success. "The hiring of parent coordinators has been one of the most positive aspects of the Children First initiative," said Digna Sanchez, president of Learning Leaders, a volunteer program.

But some parents are less impressed. "Parent coordinators are simply middlemen who do nothing but deflect the parents away from the administration," said Colon. "They're a buffer between you and the people who have the answers."

THE TWEED CULTURE

Regardless of what they think about the substance of the reforms, many observers fault the way the changes have been made. The criticism of Klein's management style occurs again and again. "Everybody in the school system except for people at Tweed are frustrated," said Anat Jacobson, spokesperson for Betsy Gotbaum. "Everything has been done behind closed doors and people don't find out about it until something goes wrong."

Because the leaders at Tweed do not consult before instituting new programs, Levy said, "there is little time to clean up these programs prior to rolling them out." The lack of discussion, she said, contributed to the problems with high school admissions and some of the testing programs. Parents too are often ignored and do not have elected board members to turn to for help.

The firing of the dissident members of the Panel for Educational Policy provided ample evidence that this system was one of strong central control. And many New Yorkers, frustrated with the bickering that crippled the schools system for decades, may welcome that. There was, Beam said, "a lot of feeling that something had to give. That's why people are not yelling too loudly."

But some are.

In an op-ed in the New York Times, education expert Diane Ravitch and teachers union president Randi Weingarten wrote, "The school system has been reorganized along the lines of a corporate business model, as though educating children was no different from selling toothpaste. … Not only does the reorganization leave out any role for public involvement, it has also led to serious malfunctioning of school services."

"Everyone complains about the almost pathological secrecy at the Department of Education," wrote Jack Newfield. "This secrecy seems mostly a defense mechanism to conceal amateurish incompetence."

In the interview, Klein denied that top leaders at the Department of Education do not consult with others. But he said, what "is different from the old system, and this I think is good, is that there wasn't a plebiscite on each and every decision. That's the way the board used to work and that was the politics of paralysis."

"The essence of mayoral accountability," the chancellor continued, "is to have the mayor able to implement changes . . . and to be able to hold him accountable for its results."

For Bloomberg, after a year with some setbacks and some successes, that remains both a promise and danger.