New York City Residents and Economy are Generating an Increasingly Large Share of State Government Resources

(photo: Mike Groll/Office of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo)

New York City and its economy have been growing at an extraordinary pace in recent years - it is quite clear that the city is generating jobs, development, and wealth. It continues to have major problems - affordable housing and homelessness crises, a deteriorated mass transit system, and nearly 20% of its population still trapped in poverty - but its overall economy has been growing.

This growth is occurring in the context of a set of perennial questions, both during state budget season when the allocation of resources across the state is decided every winter, and during campaign season, when most of the competitive legislative districts, especially for the State Senate this election year, are actually outside New York City.

Those questions are: What is the place of New York City in the state economy? Is the city a drain on the resources of the rest of the state’s residents, or a net contributor to the rest of the state? Should the city be forced to pay more to the state, or less? In the campaigns outside the city, a standard Republican refrain is to persuade voters to stick with the Republicans or lose power to “New York City Democrats,“ which presumably means there is a danger to out-of-city residents that more of their tax dollars will be spent on urban problems.

Ideally, of course, the state’s policies should allocate resources based on meeting the needs of all the people of the state in every region, rather than merely sending back equal amounts of money to the communities the dollars came from on the basis of how much they contributed in taxes. But one thing is true: the idea that New York City is a drain on the resources of the rest of the state’s regions and residents is absolutely not accurate.

The Rockefeller Institute of Government, a research institute affiliated with the State University of New York, in 2011 analyzed the basic question of where the money for New York State comes from by region, and where it is then spent by region, and confirmed that New York City is a net contributor to the state of New York as a whole. The data came from the State 2009-10 Fiscal Year, nine years ago. This article looks at trends since that time, but the evidence only shows that New York City residents and the city economy are providing an ever larger share of the State’s resources.

The City’s Status in 2009

The New York City economy’s strength in providing revenue to the state might seem intuitively obvious these days, but more surprising is that the Rockefeller Institute study showed that the city does not receive in spending its per capita share of the state’s population. As a member of the state Assembly at budget hearings over the years, I would listen to Republican state senators complain about the Medicaid program, and, guess what, they were right! Maybe not about the program’s overall value or burden, but about the fact that a lot of money in that program does go to New York City, which took 62% of the expenditure of the state-funds-only part of the Medicaid program. It was practically everything else that went the other way, with less funding to New York City and more elsewhere.

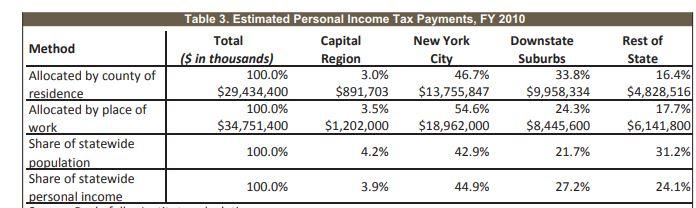

When you added in the state universities, the state prisons, and psychiatric hospitals, other state hospitals, the road, bridge, and highway spending, and even state aid to elementary and secondary education, the totality of the expenditures brought the city’s share of the state-funds-only budget to 40% of spending, while the city’s share of the population then was 42.9%, as pictured in this table from the study:

“Giving and Getting: Regional Distribution of Revenue & Spending in the NY State Budget, Fiscal Year 2009-10,” Rockefeller Institute of Government 2011

Local Assistance grants in the table above included both the Medicaid program and Aid to Education, revenue sharing, community colleges, and property tax relief spending (where the state gave school districts money in compensation for lost revenue from the STAR property tax exemptions for homeowners, where the districts lost funds). The average of all of the Local Assistance programs came to 49% for the city, but in two other large categories of spending, State agencies and State Capital Projects, the City amounted to less than one quarter of the spending, resulting in the overall 40% share.

The City’s Contribution to State Resources in 2009

The source of the state’s tax and other revenues, even in 2009, exceeded New York City’s per capita share of the state’s population, whether calculated from the residents of the city only, or the city as a place of work (Rockefeller study):

![]()

![]()

The city economy’s share of the state’s tax and other receipts in 2009 (48.7%) is partly explained by the large number of New Jersey, Connecticut, and other non-residents who work in the City and pay nonresident income taxes. About 14% of the state’s income taxes come from nonresidents. The city residents’ share of state revenues also exceeded its share of the population in 2009 (45.1 vs. 42.9), reflecting a combination of some very high-income and low-income taxpayers and residents. The city’s overall status in the state in terms of income and shares in 2009 is also reflected in this table:

New York City’s Status Today

The city’s economy is now providing a far higher share of state revenue than in 2009, during the national recession. I estimate the share based on residency now reaches 50%, and the share as a place of work reaches 53% or more.

In 2009, the city’s share of the state’s employment was 43%, but the City has gained 715,000 jobs out of 977,000 gained statewide between 2009 and 2017, according to state labor department data, and now stands at over 46% of state employment. The city was home to 44.9% of the state’s personal income in 2009, produced 45.1 % of state revenue from its residents, and 48.7% of state revenue as a place of work (Rockefeller study). A New York State Assembly economic report showed the city’s status as of 2016.

New York State Assembly 2018 Economic and Revenue Report

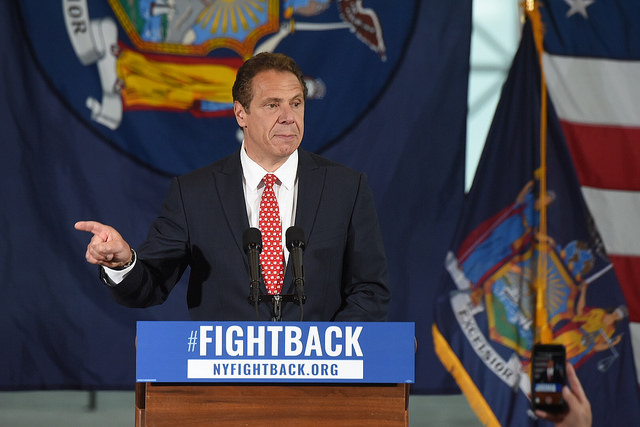

According to the Assembly economic report, the city’s share of the state’s personal income was 46.6% in 2016, higher than the 44.9% in 2009. If the same proportion for resident revenue share and place of work share held from 2009 to 2016, the city share of state revenue rises to 46.8% as a place of residence, and 50.4% as a place of work. Personal income statistics do not include capital gains income, but it is a source of income tax revenue. Capital gains income was severely depressed in 2009 due to the recession. In 2018, several billion more dollars in income tax revenue from capital gains, heavily concentrated among wealthy New York City residents, has significantly increased New York City’s share of state revenue, above and beyond the general growth in jobs and income. The following table from the state Division of the Budget shows the impact of the recession:

New York State Division of Budget, Economic & Revenue Outlook, 2012-2013, p.145

![]()

The table shows the spectacular $84 billion drop in capital gains in New York between 2007 and 2009 -- from $118 to $33.9 billion -- and the Rockefeller Institute report data reflects the low level of tax revenue from that year.

What about now?

New York State Division of Budget, Economic & Revenue Outlook, 2018-2019, p.111

![]()

Capital gains realizations for income tax purposes have risen $66 billion since 2009 to the 2019 state estimate, from $33.9 to $100.2 billion.

What does that mean for New York City?

The state Division of the Budget estimates that the top 1% of New York taxpayers pay 42-43% of the state’s income tax liability. What about in the city? A New York City Independent Budget Office study of city tax returns showed that in 2014 the top 1% of New York City residents paid $9.9 billion in state income taxes, which is about 60% of the tax liability of the top 1% of New York State taxpayers that year. Division of Budget figures also show that the top 1% of taxpayers have about 80% of capital gains income, meaning most of the tax revenue from capital gains comes from the wealthiest taxpayers. Income taxes provide 60% of state tax revenue.

The New York City Economy Share of State Tax & Other Receipts Now Reaches 53% or More

I estimate that when New York’s tax rates on upper-income and super-wealthy taxpayers are applied to the extra $66 billion in capital gains income, the city’s share of total state revenue moves up two-and-a-half percentage points, reflecting about $2.5 billion more paid in income taxes from capital gains out of an additional roughly $4.5 billion in income taxes from capital gains paid statewide -- using $78 billion in receipts in 2009 and $106 billion in 2019 as the bases for the calculations. An extra two-and-a-half points bring the city’s share from 50.4% to about 53% of total revenue payments. The overall concentration of growth in New York City likely also brought in more sales tax, real estate transfer tax, and other revenue, bringing the share to more than 53% of state revenue, ten points higher than the city’s 43% share of the state population. On the resident side the share should be at least 50%.

The State Spending Side Today

On the spending side of the equation I don’t believe there are significant differences from 2009 in terms of percentages. There have been many changes in the ensuing years but they tend to cancel each other out.

New York City’s revenue sharing from the state, which was $246 million in 2009, was eliminated that year. The state enacted a new property tax relief program worth $1 billion a year that provides rebates exclusively outside New York City, in addition to the STAR program. Governor Cuomo and the Legislature agreed in 2012 to a 2% property tax increase cap for municipalities outside New York City, along with an agreement for the state to absorb all additional local government Medicaid expenses above their 2012 spending base, including New York City’s obligation. This freeze on local Medicaid spending had the effect of helping both the city and the counties outside the city in the same proportion as the overall regional expenditure for the Medicaid program. The city’s gain from the Medicaid freeze was offset by the loss of revenue sharing and the added property tax relief spending outside the city on a regional allocation basis.

In 2014 Mayor de Blasio sought and won a universal full-day prekindergarten program, worth $300 million a year from the state. But the money ended up incorporated in the city’s overall share of Aid to Education, which stayed at the same 39% of total aid from the state as it had been for years before that.

In 2016 the state approved a new Capital Spending program for the MTA, but the State Senate insisted on parity for Highway, Road, and Bridge spending, and a capital program of $27 billion for road and bridge work was adopted at the same time, most of which is spent outside the city. The state received more than $10 billion in funds from legal settlements with financial institutions related to recession-era wrongdoing, and applied large portions of the funds to upstate economic development and infrastructure projects.

The state also cut taxes extensively during the Cuomo years, including corporate, estate, and income taxes (a high rate was maintained on incomes now above $2.1 million per year), but these policies tended to concentrate tax payments into the upper income brackets and thus concentrate them in the city, as discussed above.

How these changes will affect future budgets is uncertain, but the facts are that the New York City economy keeps generating a larger share of state resources while the city does not receive an outsize proportion of state spending.

***

Jim Brennan was a member of the New York State Assembly for 32 years, where he chaired four committees. On Twitter @JimBrennanNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

[Updated] Can Democrats win the state Senate? How progressive is Cuomo? New Yorkers are about to find out

Gov. Cuomo (photo via New York Democratic Party)

This op-ed is an updated version of a previously published column, now accounting for the October 32-day Pre-General Campaign Financial Disclosure and incorporating other new information, including reader feedback from the original version, previously published in Gotham Gazette October 2.

In the November 6 general election, New York Democrats have a historic opportunity to take control of the state Senate. If this happens, Democrats would control both houses of the state Legislature for only the third time in the last 100 years, unlocking years of bottled up progressive legislation passed by the Democratically-controlled Assembly but blocked by the Republican-controlled Senate.

Assuming Governor Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, wins reelection as he is expected to, a number of these bills may very well land on his desk, including those related to universal health care; election, voting and campaign finance reforms; reproductive health rights; equal education funding for city schools; equal protections for LGBT and disabled people; carbon emissions elimination; immigration protections, including making New York a sanctuary state; and criminal justice reforms.

Recent history might temper optimism, however. New York Democratic voters chose the status quo over the bold reforms represented by the Cynthia Nixon-Jumaane Williams-Zephyr Teachout slate in September’s primaries and in last year’s constitutional convention ballot referendum. In the 2016 state Senate races, 98% of incumbents were re-elected.

We’ll soon see how powerful New York’s blue wave really is, both on Election Day and in the legislative session that will follow beginning in January. A few key questions:

But didn’t progressives just defeat the IDC?

Sort of and it’s insufficient.

Before the primary, there were actually more “Democrats” in the state Senate than Republicans, even though the GOP conference held a 40-23, then 32-31 majority in the 63-seat chamber.

Nine Democrats were either part of the Republican conference or in a power-sharing agreement via the Independent Democratic Conference (IDC), giving the GOP a majority for the recent two-year legislative session (and prior) and preventing progressive legislation from reaching the Senate floor. Eight of those senators were members of the IDC, which did rejoin the “mainline” Democratic conference in April, after a new state budget had been passed, which led to the 32-31 GOP majority for the final months of the session that ended in June.

In the September 13 primary, six former IDC members were defeated. The ninth rogue Democrat, Senator Simcha Felder of Brooklyn, has been part of the Republican Conference for multiple terms, and was even reelected in 2016 on both the Democratic and Republican ballot lines. He won his primary challenge last month.

Despite losing in the Democratic primary, all six defeated former IDC members are likely to remain on November’s ballot on other party lines, often the Independence Party and/or Women’s Equality Party. The October filings indicate that the six defeated IDC members did not have any meaningful campaign activity in the post-primary weeks, but Senator Tony Avella has declared he is campaigning to win in the general election, and neither Senator Jeff Klein nor Senator Jesse Hamilton has formally declared their intentions. Democratic Party leaders may try to reward defeated IDC members -- like former conference leader Klein and Hamilton -- with judgeships to keep them from actively campaigning.

Surviving former IDC Senators David Carlucci and Diane Savino, along with Felder, will almost certainly win re-election in November.

What do Democrats really need to do?

Net one seat. If Democrats flip just one GOP-held Senate seat and hold onto those they currently have, then Democrats will have a real 32-31 majority heading into next year. Competitive Senate races exist on Long Island and upstate, including several districts where Democrats failed to run any candidate at all in 2016.

What’s possible?

Flipping ten seats. My most optimistic scenario has Democrats flipping ten GOP-held seats and holding onto their own, for a 41-22 majority.

If the primaries were any indicator, November turnout will be high, which will benefit Democrats due to their two-to-one registration advantage across the state. Primary turnout more than doubled since the last comparable election in 2014. In Long Island’s Nassau and Suffolk counties, Democratic primary turnout actually tripled from 2014 to this year.

Democrats are mounting competitive races in the five GOP-held districts where the current officeholder is retiring. In 2012, Obama carried all of those districts; In 2016, Clinton carried one and Trump won by 6% or less in the other four. Democrats are also contesting several other races where the Republican incumbent is seen as beatable.

Below is my list for the best opportunities for Democrats to flip GOP-held Senate seats, categorized as “Most likely to flip,” “Highly competitive,” and “Long-shots.” You can see the full detailed spreadsheet here.

In compiling this list, I considered voter registration differential, popularity as measured by the number of individual campaign contributors, money including party funding, voting results by state Senate in the two most recent presidential elections, the power of incumbency, and signals of grassroots activism.

Money matters -- to pay for campaign staff, advertising, get-out-the-vote efforts, and more. The table above includes the most recent Board of Elections campaign disclosures, filed by October 1. Grassroots support can certainly counteract big money, as IDC challenger Alessandra Biaggi demonstrated in her primary defeat of former IDC leader Klein, but it’s difficult to conceive how other candidates could overcome comparable odds. Klein outspent Biaggi nearly seven-to-one -- $2.8 million to Biaggi’s $414,457 -- but Biaggi raised money from 47 times the number of contributors that Klein had.

Past voter preferences matter, especially since they don’t necessarily follow in line with voter registration data. The 2012 presidential election was more reflective of deeply felt beliefs in these districts, which had with one exception solid pluralities for Obama. Democratic voters who stayed home may have contributed to the mixed results of the 2016 election. By this year, 2016’s GOP victories didn’t deter -- and perhaps motivated -- Democratic contributors and may have awakened Democrats who came out in droves to vote in this year’s primaries. In addition, changing demographics have also affected these districts in ways that potentially favor progressive Democratic candidates.

Party money also matters. Both Democrats and Republicans have state Senate campaign committees, which have injected money into select races as shown on my chart. The full extent of Cuomo’s financial support remains to be seen.

What’s the rundown on the races?

James Skoufis vs. Tom Basile (SD-39): Assemblymember Skoufis has a solid lead in every respect that should offset the weak Democratic performance in the past presidential elections. The significant GOP support for Basile signals the party’s concern. Even after the GOP’s $288,300 investment, Skoufis had a commanding 9.5 times more money as of the most recent filing.

Jen Lunsford vs. Rich Funke (SD-55); Anna Kaplan vs. Elaine Phillips (SD-7), Karen Smythe vs. Sue Serino (SD-41): These three races occur in districts with vulnerable GOP incumbents. In all three, huge Democratic Party enrollment and presidential voting advantages could overcome GOP funding advantages. In SD-7, the GOP is concerned enough to invest $254,500 to prop up incumbent Senator Phillips.

Jeremy Cooney vs. Joseph Robach (SD-56): Jeremy Cooney has everything going for him -- but money. He’s in a heavily Democratic district that came out big for Obama and Clinton. His grassroots popularity is reflected in the number of individual donations. But his relatively low cash balance against a well-funded incumbent, Senator Robach, is so large that the GOP seems to have decided Robach doesn’t need additional help.

Jim Gaughran vs. Carl Marcellino (SD-5): This district may define the red-to-blue wave as it is one of the few in the country that flipped from voting Republican to Democrat between the 2012 and 2016 presidential elections, perhaps indicating a demographic shift. As of September, Gaughran and Marcellino had roughly the same balance remaining in their campaign accounts, motivating both parties to pony up for the final weeks of the campaign. GOP support gives Marcellino an edge in overall funding that Gaughran’s enthusiastic grassroots supporters can overcome, especially since Marcellino only won by 1.2% in 2016 over Gaughran.

Jen Metzger vs. Annie Rabbitt (SD-42) and Monica Martinez vs. Dean Murray (SD-3): Both of these districts were solid Trump districts in 2016 after having been solid Obama districts in 2012. Both enjoy large Democratic majorities and no incumbents. Metzger and Martinez are also winning the hearts and dollars of individual contributors over their GOP opponents. Metzger’s impressive overall campaign funding advantage of 1.8 times Rabbitt is solid; Martinez’s deficit to Murray of 1.4 times her fundraising can also be surmounted by a strong grassroots effort down the stretch.

Andrew Gounardes vs. Marty Golden (SD-22): This Southern Brooklyn seat represents why many GOP-held districts are vulnerable. Since 2012, when incumbent Republican Senator Golden won his last competitive race, the district’s demographics have changed dramatically. Today, 40% of residents are now people of color, especially Asian and Hispanic; and 43% are immigrants, primarily Asian, eastern European, and Mexican. Residents work in blue-collar industries like transportation, wholesale, and construction. Virtually every racial group earns less than the median for New York State. These changes create the setting for the red-to-blue opportunity for progressive Democrat Gounardes, Golden’s opponent in 2012.

In less than 30 days between the post-primary and the October filings, Gounardes has substantially narrowed the funding gap with Golden after having spent significantly during a hard-fought Democratic primary. Golden’s 7 times funding advantage shunk to 2.3 times with the help of the state Senate campaign fund. The lopsided Democratic registration advantage in the district is a red herring; some of the district’s constituents register as Democrats in order to have a say in New York City primaries, but vote GOP in the general election. Many registered Democrats in the district have voted Republican in mayoral and other elections for years. [Disclosure: I’m a member of Gounardes’ finance committee.]

Aaron Gladd vs. Daphne Jordan (SD-43): This district is a conundrum. The GOP enjoys a strong registration advantage but went for Obama in 2012 and narrowly chose Trump in 2016. Gladd’s advantage in contributors and overall funding sufficiently concerns the GOP enough to drop money to support Jordan.

Lou D’Amaro vs. Phil Boyle (SD-4) and John Mannion vs. Bob Antonacci (SD-50): In both races, the GOP is winning on number of contributors and overall funding balance going into the final weeks of the election. Mannion’s situation may be so bleak that the Democrats have thrown a pile of cash into this race, while the GOP, smelling a potential win, has also invested.

Kevin Thomas vs. Kemp Hannon (SD-6) and Pete Harckham vs. Terrence Murphy (SD-40): It’s very hard to imagine that Thomas and Harckham can overcome the massive campaign balance deficits as compared to their GOP opponents in the waning weeks of the election.

Aren’t there Democrats at risk?

Incumbent Democrats appear safe. John Brooks in Senate District 8 on Long Island is often mentioned as a potential risk, probably due to his narrow 214-vote (0.2%) win in 2016 over then-incumbent GOP Senator Michael Venditto. But now-incumbent Brooks has a solid fundraising lead over his GOP challenger, Jeff Pravato, in a district that went for Obama and Clinton and has a solid Democratic voter registration advantage.

Democrats need to ensure that primary victors Rachel May in SD-53 and Alessandra Biaggi in SD-34, both of whom beat IDC members, continue their momentum through November. The IDC incumbents they defeated are likely to appear on other ballot lines and have significant money. May’s opponent, David Valesky, reported a $340,038 post-primary balance to May’s $41,209, though he has recently declared that he will not campaign in the general. Biaggi’s opponent, former IDC leader Klein, reported a post-primary balance of $497,267 and has not indicated his plans for the general election.

On October 8, former IDC Senator Avella of Queens, who lost in the Democratic primary to John Liu, announced that he will actively campaign in a long-shot attempt to win the November election on the Independence Party and Women’s Equality Party lines. As of the recent filing, Liu had a 3.3 times funding advantage over Avella and an energized and active campaign operation.

So what’s going to happen?

On November 6, Democrats will take control of the New York State Senate with a solid majority that Republicans cannot hold back. This, along with holding onto a wide majority in the Assembly, will likely result in a steady stream of progressive legislation on the governor’s desk to sign, giving Cuomo the opportunity to make history New York has been waiting for.

***

Art Chang is a writer, thinker and strategist at the intersection of technology and government. He is a former board member of New York City’s Campaign Finance Board, where he led the creation of NYC Votes and Voting.NYC. On Twitter @achangnyc.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

In Need of Partners: Affordability Gap Too Large for New York City to Cover Alone

(photo: @NYCHousing)

New York City is a city of renters, and affordable housing is a perennial concern of New Yorkers. Under Mayor Bill de Blasio, the city has committed an unprecedented level of resources to create and preserve affordable housing units and make critical repairs at the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). But is it realistic to think the city can address affordability for all rent-burdened New Yorkers?

A new report from Citizens Budget Commission (CBC) indicates rental burdens have not improved since 2014, and are most severe for low-income single households, particularly single seniors. The most effective programs for providing low-income, affordable housing have been federally funded; the city cannot handle the affordability problem on its own.

CBC analysis of data from the 2017 Housing Vacancy Survey (HVS) shows more than 921,000 renter households in New York City, or 44 percent of all renters, pay at least 30 percent of their income in rent, even after accounting for the value of federal rental housing vouchers and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits (food stamps). Twenty-two percent of households – more than 462,000 families and single adults – are severely rent burdened, which means they pay 50 percent or more of their income in rent.

Severe rent burdens disproportionately affect single households: 35 percent of single seniors, 27 percent of single households, and 26 percent of single-parent households were low-income and severely burdened. In contrast, about 15 percent of households with multiple adults were low-income and severely burdened.

These findings are largely unchanged from the last time the HVS was conducted in 2014. The share of rent-burdened households increased to 44 percent from 42 percent, while the share of severely burdened remained unchanged. Severe burdens increased slightly among low-income single households and seniors.

The primary challenge in tackling the “affordability gap” is that the lowest income households require subsidies to supplement what they can afford to pay in rent. Historically, federal housing programs have been most effective at addressing these needs. According to the 2017 HVS, two-thirds of the lowest income households that are not rent burdened either reside in federally-subsidized public housing or receive Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers. Most of the remaining third benefit from some other form of subsidy from the city, state or federal governments.

While city government has a role to play in addressing rental burdens, it is unrealistic to expect the city to close the gap on its own. The number of extremely and very low income New York City households that pay half their income in rent exceeds the mayor’s entire 300,000-unit housing plan. Meanwhile, NYCHA faces a $32 billion capital need, and its public housing units are in the worst condition of all rental housing in the city. The cost of addressing these challenges vastly exceeds the city’s financial resources. Any meaningful response to preserve public housing and address the housing needs of severely rent burdened New Yorkers will require willing partners in Albany and Washington.

***

Sean Campion is a senior research associate for Citizens Budget Commission. On Twitter @cbcny.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.