Eric Garner's Final Words, One Year Later

An NYPD press conference (photo: @NYPDnews)

For good reason, Eric Garner's last words are well remembered. "I can't breathe" -- repeated 11 times by the dying man and ignored by the officers who had jumped on him, choked him, and forced his body to the ground. These are words, along with "Black Lives Matter," advocates for police reform across our country chant while marching and put on their clothing and protest placards.

Also significant were the words Garner spoke at the beginning of the video that showed the officers' reckless and excessive use of force and Garner's last moments. "This stops today," he said with his hands raised. Although he probably did not conceive the meaning of the words in this way, he was clearly referring to harassment he felt he experienced from 'broken windows' policing and its harsh effects on his life. Police actions on July 17 of last year would have been the ninth time officers had arrested Garner for selling loose cigarettes. His "this stops today" was, in effect, his protest against this approach to law enforcement; his stating that he is not a criminal, he is not engaged in predatory conduct; his asking, in effect, 'why are you harassing me?'; 'why aren't you fighting real crime that threatens and disrupts my community?'

Many New Yorkers and Americans fervently hope that Eric Garner did not die in vain, that his death so powerfully imprinted on the public mind's eye will lead to changes in the practices that directly contributed to his brutal end. It is undeniable that, among the things that this tragic incident reflected, central was the reality that it was a dramatic case of 'broken windows' policing gone terribly, terribly wrong. So have the city's officials, led in this instance by Mayor Bill de Blasio and Police Commissioner Bill Bratton, taken meaningful steps to correct or abandon 'broken windows' or to make city law enforcement practices more fair? The answer, despite the superficial reforms rolled out periodically by de Blasio and Bratton, is an unqualified "No."

Training officers in how to take in New Yorkers resisting arrest or how to treat people more respectfully? Officers see the training as public relations exercises with little relevance to their day-to-day duties on the street. As long as the problematic policies persist — in this case, 'broken windows' policing — no meaningful change in cops' conduct will result from additional training.

Ticketing New Yorkers, rather than arresting them, for marijuana possession? This step does nothing to eliminate the racial bias associated with marijuana enforcement — over 85 percent of marijuana possession arrests and summonses still involve African-Americans or Latinos, although studies show that the majority of people who use and sell the drug are white. Besides, in our court monitoring work, PROP volunteers have seen many instances where people, almost always New Yorkers of color, have been arrested for possessing small amounts of marijuana, real or synthetic.

Body cameras on police officers? It makes sense that in some cases cameras might curtail aggressive policing. Of course, cynics could reasonably think and say that if the Garner video, with all its compelling visible evidence on display did not lead to any police accountability, why should we trust that film that remains in the NYPD's hands will have any benign effect?

De Blasio and Bratton have continued their enthusiastic embrace of 'broken windows' practices that involve mainly arresting and ticketing African-American and Latino individuals, sometimes on bogus charges, for engaging in minor infractions that have been virtually decriminalized in the city's white neighborhoods. PROP's Court Monitoring Project regularly visits the arraignment parts of the city's criminal courts where our volunteers observe and record who the police are arresting and on what charges. We have attended ten court sessions in the last two months in the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Manhattan - our findings reflect an up-to-date picture of NYPD arrest practices. Of the 268 cases observed, 250 - or 93.3 percent - involved New Yorkers of color. Charges included park after dark, open alcohol container, jaywalking, marijuana possession, and "unlawful solicitation" (usually when the police arrest someone who has asked another person to swipe him/her into the subway).

Police had arrested all these people, cuffed and confined them, and kept most of them locked up overnight. Some charges that the court officer or judge stated out loud in the courtroom included "man-spreading" on the subway; "the unauthorized selling of smoothies in Central Park"; "the unlicensed practice of massage"; and "the selling of bottled water on a public road." Current police practices are not only blatantly racist and wasteful, they sometimes border on the surreal.

In a July column published in the Daily News, Eric Garner's 20-year-old son Eric Snipes wrote: "I don't think things have gotten better because cops are still out there harassing people. I've been stopped by cops. They just come over and ask me for my ID and pat me down. But if I was white, walking in a white neighborhood, they wouldn't do that. They need to stop discriminating."

The challenge for us advocates and for every New Yorker, in Eric Garner's name and on behalf of justice for all people, is to keep the pressure on, to keep the spotlight on biased and abusive policing until city leaders fully and completely "stop discriminating."

***

Robert Gangi is the director of the Police Reform Organizing Project (PROP). Find PROP online at its website and on Facebook and Twitter.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Solution to Homelessness is Housing, Not Policing

A sleep-in protester with the message (photo: @VOCALNewYork)

Mayor de Blasio and Commissioner Bratton were confronted by the growing disorder associated with homeless mentally ill people at a press conference on Wednesday. The mayor responded that the city is both relying on aggressive “quality of life” policing and attempting to develop supportive housing to try to address the roots of the problem. This is a refreshing alternative to the liberal approach of the Dinkins years in which people were told that they needed to tolerate a certain amount of disorder while long term solutions were pursued, many of which were out of reach, we were told, given federal budget cuts.

De Blasio has consistently voiced his support for using the police to maintain order as well as fight crime, sometimes spuriously linking the two under the banner of the “broken windows” theory. He has also called for a significant expansion of both supportive housing for the homeless and affordable housing more broadly. But is his approach really going to work any better for either homeless people or local residents? Are cops really the ones who should be so regularly on the front lines of addressing mentally ill people on New York City streets?

In the early 1990s New York City faced a significant crisis of public order related to the growth of mass homelessness and the breakdown of the State’s mental health system. Neighborhoods throughout the city were confronted by homeless encampments, wide spread panhandling, squeegee men, and at times the menacing and even violent behavior of mentally ill people living on the streets and subways. The system of policing, emergency shelters, and mental health care seemed powerless to deal with people like Larry Hogue who for years threatened, annoyed, and at times assaulted residents along West 96 Street. Despite repeated arrests and hospitalizations, he would always return to the neighborhood and continue his anti-social behaviors. The city spent hundreds of thousands of dollars processing him through police precincts, courts, jails, and emergency rooms, with no positive outcomes for either him or local residents. Hogue was eventually subjected to a year’s imprisonment on assault charges followed by a long-term psychiatric commitment at Creedmoor State Hospital.

The sense of a city out of control during this period contributed to the political rise of Rudolph Giuliani and a police-centered approach to dealing with the homeless mentally ill. For some time that approach significantly reduced the public impact of mass homelessness, but only by undermining homeless people’s civil rights and personal dignity, and substantially increasing the rolls of the mentally ill in city jails and state prisons. However, no real progress has been made on improving our mental health infrastructure or reducing homelessness. In fact, homelessness has been on the rise almost every year since the early ‘90s with nearly 60,000 people currently in the shelter system and thousands more sleeping out of doors each night.

The New York Post recently chronicled the rise of a new homeless denizen of the Upper West side who, like Hogue, suffers from severe mental illness and has been unresponsive to repeated arrest and emergency hospitalization. While the Post’s breathless coverage has the feel of moral panic designed to undermine the mayor’s overall credibility, the number of people sleeping on streets, in subways, and even occupying Tompkins Square Park has increased.

The mayor and police commissioner pointed out to reporters that they have invested in significant new training for police in how to deal with the mentally ill. Over the next few years 10,000 officers will undergo four days of specialized training in dealing with a wide variety of potential interactions in hopes of reducing the spate of fatal outcomes, seen nationally, in which police kill people experiencing a mental health crisis. They are also being made aware of the emergency services available for people on the streets and how to use verbal skills to deescalate contentious interactions and coax people into services and more socially acceptable behaviors.

There are several problems with this approach, however. First, there aren’t really any meaningful services to coax people into. People who are homeless and mentally ill are likely to experience repeated and prolonged periods of crisis. The main service available to them is emergency mental health hospitalization, in which people are held for a few hours or a few days, given medication until they appear stable, and then released back onto the streets, often leading to either chronic under-treatment or a very expensive and often ineffective revolving door between jails and hospitals, as recently chronicled in the New York Times.

Second, armed uniformed police really aren’t the best people to assign to this important task. Over the last generation we have seen a dramatic shifting of local resources away from social services and towards police and prisons. Emotionally disturbed person (EDP) calls make up a significant part of patrol officers’ time and up to 30-50 percent of people at Rikers Island have a major diagnosed mental illness—all at tremendous public expense.

The primary function of police is to use force and coercion to enforce the law. As such they develop a mindset that sees the world as full of potential threats and feel a profound need to command authority and obedience in interactions with the public, ironically in an effort to avoid actually having to use force against people. Those experiencing a mental health crisis, however, do not typically respond well to that police demeanor. Attempting to train officers in a new demeanor, while desirable, is unlikely to be very successful given the profound pressures to maintain an authoritative public profile.

In reality, when police are involved they tend to fall back on their core approach which is criminalization and coercion. Since Bratton’s return we have seen a continuation of hostile and prejudicial policing targeting homeless people on the streets and subways. While “stop and frisk” numbers are down, misdemeanor arrests and summonses for the kinds of activities associated with homelessness remain shockingly high.

Recent court monitoring by the Police Reform Organizing Project uncovered multiple cases of homeless people being arrested and ticketed for minor violations like taking up two seats in the subway and being in the park after dark. Jena Rice and Marcus Moore from Picture the Homeless pointed out in the Daily News that the ongoing criminalization of homeless people “defeats the purpose if one part of the administration takes productive steps to address housing, while the NYPD sets homeless New Yorkers back by unnecessarily giving them criminal records and making it harder to maintain employment and self-sufficiency.”

Rather than relying on the police, we need to utilize trained mental health workers. The city has a few crisis intervention teams, staffed with trained clinicians, but they have limited hours and are not well connected to 911, meaning that it is usually the police who are dispatched first. The city also has civilian outreach teams, but they are small in number and lack access to meaningful services. Other cities have developed more robust crisis intervention teams that are the primary response mechanism and outreach teams who can develop individualized case management plans to deal with more chronic situations. In either case, the outcomes are better and the costs are lower.

Of course such an approach requires the presence of meaningful mental health and housing services for people to be referred to. When those services exist, people’s lives are stabilized and the burden on the rest of us as residents or tax-payers is reduced. Recent studies in Los Angeles, Salt Lake City, Denver, Boston, and other areas show that providing people with supportive housing through “housing first” initiatives is cheaper and more effective than leaving them homeless and cycling through shelters, jails, and emergency rooms. New York has supportive housing, but it is not enough and is losing state funding.

The mayor has pointed out that First Lady Chirlane McCray is engaged in a top-to-bottom review of the city’s mental health services, with a focus on the criminal justice system. This is good news and hopefully will include more services and mechanisms for working with people in crisis that don’t involve the police, courts, and jails. Significant help from the state will probably be necessary to make any major improvements, something for which neither the current nor previous Governor Cuomo has been known for.

There is another problem with the mayor’s response on Wednesday, which is that his calls for supportive and affordable housing seem thin. While the mayor has proposed 200,000 new and saved affordable units, to be obtained mostly through inclusionary housing in which zoning limits are increased in return for more “affordable” units being included. The problem is that almost none of them would be affordable to homeless people. According to Jennifer Flynn at VOCAL New York, the plan only has about 1,250 supportive housing units in which people receive permanent housing with a variety of mental health, substance abuse, and employment services. The mayor is hoping the governor will renew the NY-NY program, which might add another 30,000 units over several years, but this still falls far short of the growing demand.

In response, a large coalition of community-based groups, service providers, and yes, construction unions is calling for a major increase in capital spending to build 15,000 units of supportive housing for currently homeless New Yorkers. To press the cause, they held a sleep-in overnight Thursday at the long undeveloped Seward Park site in the Lower East Side.

Mayor de Blasio learned from the ‘90s that disorder matters. Unfortunately, the lesson he took away was that aggressive policing is a necessary part of managing mass homelessness and that affordable housing is something primarily for the middle class and working poor. With the growing numbers of homeless people and the inadequacies of our mental health infrastructure this approach may have run its course. We can’t criminalize our way out of homelessness and we can’t solve it with middle class housing schemes. The city must invest new capital dollars in substantial new housing that directly targets the poorest and most vulnerable - and at times disorderly - New Yorkers. That is a solution that will benefit both them and the rest of us.

***

Alex S. Vitale is associate professor of sociology at Brooklyn College and author of City of Disorder: How the Quality of Life Campaign Transformed New York Politics. He is senior policy adviser to the Police Reform Organizing Project and serves on the New York State Advisory Committee to the US Civil Rights Commission. You can follow him on Twitter: @avitale

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Good and Bad News on Second Avenue Subway

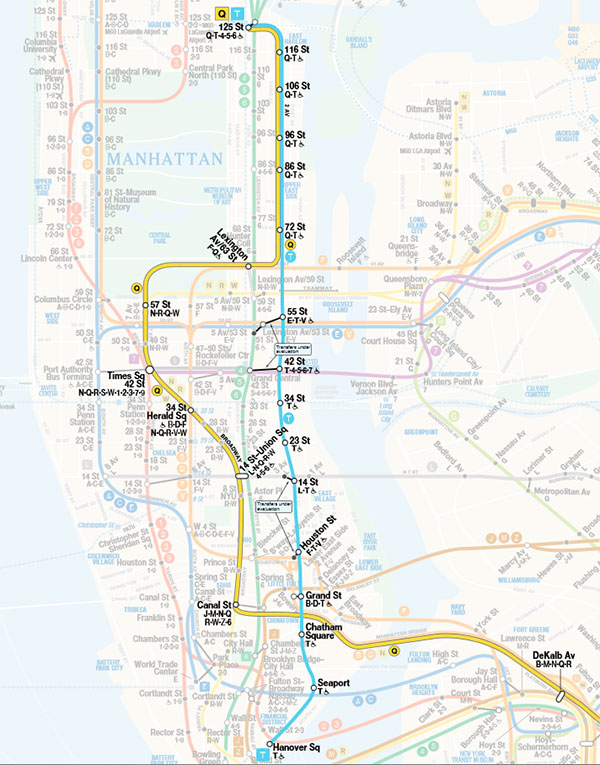

Second Avenue Subway projection (image via the MTA)

Two of the perks of being college professors are that we don't usually have to ride the subway during rush hour and we get to tell the truth about politicians. For those of you who do have to deal with the morning crush, we have both good and bad news about the mythical Second Avenue Subway.

The first section of the line, a 1.5 mile segment from 96 Street to 63 Street should open by 2017 after nearly a century of false starts. This new Upper East Side line is expected to carry about 200,000 riders per day, a higher ridership than Los Angeles's 17 mile subway system. It will connect with the Q train so that you will be able to travel from 96 Street down Second Avenue, west across 63 Street and then down Broadway without having to transfer. You will never have to actually ride under Second Avenue to appreciate its benefits though, because this segment will reduce congestion on the Lexington Avenue Line's overcrowded 4, 5, and 6 trains by more than 10 percent.

The Lexington Avenue Line is the only subway on Manhattan's east side and it already carries more passengers than the combined ridership of San Francisco, Chicago, and Boston's entire transit systems. During peak periods, passengers so crowd the subway cars and platforms that they are slowing down trains at stations, reducing the number of trains that the MTA can operate, and making the crowded conditions even worse. Once the first section of the Second Avenue Subway is completed, the Lexington Avenue Line trains will not only be less crowded, but also more reliable and faster. All good news.

When it is complete, the Second Avenue subway will be 8.5 miles long extending from East Harlem down to Lower Manhattan. The next section is supposed to include three new stations. Two of them are under Second Avenue, one at 106 Street and the other at 116 Street. The third station will provide the most benefits: 125 Street at Lexington Avenue where passengers will be able to connect with both the Lexington Avenue line and Metro-North Railroad.

Now, the bad news.

Our esteemed city leaders promised a working Second Avenue line in the 1920s, '30s, '40s, '50s, '60s, '70s, '90s, and 2000s. It's a shame that so many politicians made these promises because if they had been more realistic, the city might never have torn down the elevated train lines that once ran above Second and Third Avenues from the Bronx to the Lower Manhattan. Likewise, the MTA would not have started construction in the 1970s only to abandon tunnels a few years later.

How long will it take to complete the subway all the way to Lower Manhattan? Well, unless you're young enough that a parent is still packing you peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for school every day - maybe not in your lifetime.

The most recent incarnation of the Second Avenue Subway was born about 15 years ago when the MTA did something smart. Its planners made sure the line would be built in stages so that each stage would have benefits even if the whole line was never completed.

The state and city are now facing a major dilemma about beginning the second stage to 125 Street. The MTA is facing a massive $14 billion hole in its five-year capital program and already has over $34 billion in outstanding debt even before it begins the next phase of the Second Avenue. The MTA cannot afford to continue building the new line without outside financial help.

At the same time, two factors will make the Lexington Avenue line much more crowded. First, the city is continuing to encourage both new residential and commercial growth along the east side. Second, the MTA is completing construction of the East Side Access project that will connect the Long Island Rail Road with Grand Central Terminal where thousands of riders every day will transfer to the 42 Street station on the Lexington Avenue line.

The governor, who controls the MTA board of directors, will make the final decision about its capital program. So what will Governor Andrew Cuomo do? He has committed himself politically to limiting any increase to taxes, tolls, and fares. He is also talking about another megaproject– an elevated train connection to LaGuardia Airport. Since he has already called the MTA capital program bloated, it is clear he is going to be making cuts.

Cuomo's choices are all unpleasant for riders. The MTA could replace fewer subway cars, fix up fewer subway stations, or buy fewer new buses. It might have to postpone plans to replace tracks, signals, and its other critical and aging infrastructure. The $1.5 billion proposal for just starting the next phase of the Second Avenue Subway will clearly be one of his biggest targets.

Our guess is that he is going to announce that New York is still committed to building stage two, but he is going to take away nearly all the funds allocated for it. That is what his political advisors are probably whispering into his ear right now. Cuomo will never get credit for having the idea to build the Second Avenue Subway line and he will not be in office long enough to take credit for its completion.

The MTA doesn't really need to finish the subway line when it can just do what Tokyo does. The MTA can hire "oshiyas," outfit them in snazzy uniforms and white gloves, and have them push people onto overcrowded rush hour trains. Just think of it as an opportunity to meet, touch, and smell more of your neighbors.

If that doesn't sound like a good way to travel on the East Side in the future - and it sounds awful to us - you might want to consider calling your elected representatives.

***

by Philip M. Plotch and Nicholas D. Bloom

Plotch is an assistant professor of political science and director of the Masters in Public Administration program at Saint Peter's University in Jersey City. He is the former director of World Trade Center Redevelopment and Special Projects for the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, and the former manager of planning for New York's Metropolitan Transportation Authority. He is the author of Politics Across the Hudson: The Tappan Zee Megaproject.

Bloom is associate professor at the New York Institute of Technology where he is also Chair of Urban Administration and Interdisciplinary Studies. He has written many books including The Metropolitan Airport: JFK International and Modern New York and the forthcoming edited collection from Princeton University Press, Affordable Housing in New York: The People, Places, and Policies That Transformed a City.