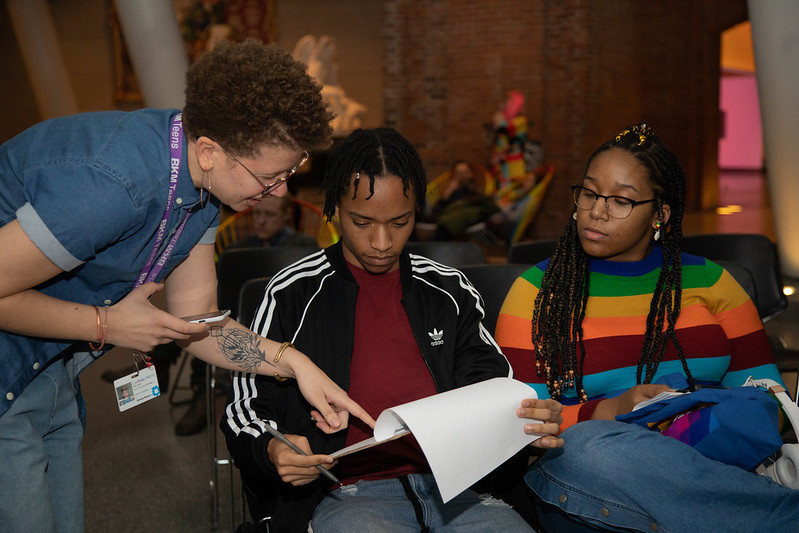

Thinking Anew About How to Finally Solve Family Homelessness in New York City

The makings of a community center (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

After 35 years running a non-profit service provider in New York City that served over 65,000 homeless families and 135,000 children, I have retired. I never could have imagined that the homeless situation in the city today would still be worse than when it all began in the 1980s. Back then, I served as First Deputy Commissioner for Homelessness in the Koch administration. After all that time, l have seen and learned a great deal about family homelessness.

First, contrary to popular belief, homelessness isn’t necessarily just about housing, as much as it’s about a family’s ability to maintain housing.

In fact, homeless families fall into three distinct groups: the first group is made up of recently-unemployed poor families with strong employment and tenancy histories. They typically become homeless due to some unexpected crisis, represent about 20% of the shelter population, and can be immediately rehoused with the greatest probability of not becoming homeless again.

The second group is comprised of mostly young, single, female heads of households with one or more young children. Many have incomplete educations and virtually no meaningful work or independent living experience. They have a difficult time maintaining housing for the long-term, exhibit a high probability of returning to shelter, and make up roughly 45% of the family shelter population.

The third group is considered chronically homeless. Many are survivors of domestic violence, experience mental health or substance abuse issues, are typically older, and experience multiple episodes of homelessness. These are the chronic users of the shelter system and represent some 35% of the population.

So, what is the answer to reducing family homelessness? Almost four decades of homelessness policies have come full circle with little to show for success. Although thousands of families have been moved to permanent housing, many still return to shelter, and thousands more keep entering the system. Simply providing housing hasn’t worked but restructuring how we provide temporary shelter and services will.

With three different groups, the one-size-fits-all policies of “housing first” will never work. Instead, the homeless family population must be triaged for short-, intermediate-, and long-term stays, and serviced within a different kind of shelter in tandem with policies targeted to their specific needs.

Those with work and tenancy experience should be immediately helped getting reemployed and rapidly rehoused; the younger, homeless heads of households must be given priority access to complete their schooling and job training for work that will enable them to maintain housing long-term; and those experiencing chronic homelessness should receive access to intensive services in a more controlled setting to effectively address the severe social problems they face—an approach that no leader has taken seriously to date or expressed the political will to meet the challenge.

During the Koch years the city built four specially-designed residential family shelters, which were to be turned into community centers when the homeless crisis ended. Although that never happened, it was a good idea. The city should refocus on that concept and replace the opening of traditional shelters with new alternative residential community centers to serve homeless families in communities of need.

They would be actual community centers with a transitional homeless residential component and a mandate to provide comprehensive job training and employment services; adult and youth educational programs; and child care and health care, among other supports, to meet not only the needs of homeless residents, but also those of the whole community at large.

They would primarily be located in feeder communities—the places with the largest number of families coming into shelter and providing triaged service levels to effectively ensure families get the appropriate help they need, while keeping them in their neighborhoods near family, friends, school, and work. Not a one-size-fits-all policy, but rather a new, multifaceted approach to the problem.

Community residential centers would help ease the NIMBY fears of having traditional homeless shelters in their communities, unlike today’s facilities. By integrating the community into facility programming alongside homeless families, not at odds with each other, but bringing resources into the community where the overarching problems can be solved together, the delivery of homeless services would be taken to a whole new level. The emphasis would be on positive, productive interactions. The end result would be to make these facilities centers of neighborhood pride rather than scorn.

For over 30 years, there has been little change in city policies to address family homelessness. Instead, new initiatives are typically old ones that have been repackaged and renamed, but new community residential centers would erase all of that. Not a traditional shelter that simply warehouses homeless people, but an educational community of opportunity and learning situated in under-resourced neighborhoods from which homeless families typically emerge. In fact, these centers could be easily sited for development on the New York City Housing Authority’s abundance of underutilized land — where better to begin?

In a city that spends over $2 billion annually on homelessness, five times what it was in 1990, community residential centers are a blueprint to the future and a cost-effective way to reduce and prevent homelessness. It is an old idea whose time has come, enhanced by lessons learned and often forgotten.

After almost four decades of this work, here is how I see it. New York City is at a crossroads. It can promise more affordable housing, but it will never be enough. It could choose to go on developing more traditional shelters, continuing the costly, ineffective policies of an ever-expanding shelter system that houses people who become homeless over and over again. Or it could begin to forge a new path forward, redefining how best to assist homeless families to achieve the stability they need in order to maintain the housing they want.

In short, a new mayor affords a new opportunity to advance a new policy to address an old nemesis and to boldly go where no mayor has gone before.

***

Ralph da Costa Nunez was President/CEO of Homes for the Homeless and the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness from 1987 to the end of 2021.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Giving People Voice, Improving Performance: New York City Should Implement Resident Satisfaction Surveys

Outreach to New Yorkers (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Mayor Adams, in launching the Dynamic Mayor’s Management report (DMMR) and the creation of a Chief Efficiency Officer, promises to “track how well we’re delivering services to New Yorkers and identifying areas where we need to improve.” The Chief Efficiency Officer is charged with developing updated performance measures to make the city more “efficient, transparent and accountable.”

Nowhere in the mayor’s April 6 statement announcing the DMMR nor in the Executive Order is there mention of the only data that measure the outcomes of city services rather than administrative inputs or outputs. Resident surveys provide a perspective on municipal services not available from other sources. As noted by the Controller’s Office for the City and County of San Francisco, “One of the most direct ways to measure the outcomes of the City’s effort – that is, the extent to which services are having their desired efforts – is to ask the users of those services.”

Use by U.S. Cities

San Francisco does it, Philadelphia does it, San Diego does it. Phoenix, Dallas, Austin, Portland, Ore., Kansas City, MO, Scottsdale, and Detroit also do it. But so do small cities, counties, and towns such as Southlake, TX (pop. 32,376), Glynn County, GA (pop. 84,500), Yountville township, CA (pop. 2,900). What they do is conduct comprehensive, uniform, recurring resident surveys as an integral feature of their performance assessment, operation, and reporting.

New York doesn’t.

Resident surveys are used widely by U.S. municipalities to evaluate the impacts and quality of their services. Among the top 10 most-populous U.S. cities in 2020, six survey their residents; the biggest four don’t.

| 1. New York | No |

| 2. Los Angeles | No |

| 3. Chicago | No |

| 4. Houston | No |

| 5. Phoenix | Yes |

| 6. Philadelphia | Yes |

| 7. San Antonio | Yes |

| 8. San Diego | Yes |

| 9. Dallas | Yes |

| 10. San Jose | Yes |

Consensus on Value of Resident Surveys

A consensus exists among government officials, management experts, and program analysts that government services must be “customer driven.” Government organizations should pay attention to residents’ perceptions and assessments of the quality of the services they provide. According to the International City and County Managers Association, “The best way to encourage good performance is to measure it, and the best indicator of government performance is citizen satisfaction.”

And the Government Accounting Standards Board says: “It is important for reported performance to include measures of citizen and customer perceptions about the results of the service or program. Without this information against which to compare other, more quantitative measures of performance, a complete picture of results is not obtained.”

Goals and Benefits of Resident Surveys

The principal goals of resident surveys are: increased resident participation, strengthened municipal management, and strengthened municipal policy-making.

Resident surveys concentrate on the outcomes or the results of government services – how satisfied people are with their schools and parks; how safe they feel in their neighborhoods. Most administrative measures focus on inputs and outputs. While these are certainly important for internal accountability, public accountability – what the public really wants from government – centers on results.

Additionally, resident surveys allow for the analysis of individual differences in how people use and experience city services – for example, differences by race, ethnicity, age, gender, income, and geography. Most administrative measures of service quality cannot identify who uses and how they are affected by the service.

In a study of what people want from local government performance reporting, the Government Accounting Standards Board found that outcomes and resident perceptions were the performance measures of most interest to the general public. The New York City Independent Budget Office has recommended that the city “identify and report on results that matter to the public and reflect the way the public sees and uses city services.”

Giving Residents Voice

Rigorously constructed and conducted and appropriately analyzed surveys give residents “voice,” enhancing the quality of governance. Resident surveys are possibly the most efficient, if not the only, way to obtain information on:

- constituents’ satisfaction with the quality of specific services and facilities, including the identification of problem areas;

- facts such as the number and characteristics of users and non-users of various services (and the frequency and form of use);

- reasons why specific services/facilities are disliked or not used;

- community needs assessment, identification of high priority but inadequate community services, potential demands for new services;

- residents’ opinions on various community issues, including feelings of confidence or trust toward government and specific agencies/officials;

- residents’ assessments of real policy options — results provide guidance (but not mandates) for official action;

- socio-economic and demographic data to complement/supplement other sources.

Resident Surveys and Policy

Resident surveys, as outcome data, can inform New York decision-makers and agency managers throughout the policy process:

- Policy formulation: Help public officials to determine what residents need, want, prefer, or demand; help make choices, set priorities, change practices;

- Policy implementation: Help public managers determine how best to deliver services. As long as respondents have some knowledge about an implementation issue, questions can concern projects, programs, procedures;

- Policy evaluation: With service delivery, the consumer’s perception is the pertinent reality. Even the most efficient department is not doing its job well if residents are not satisfied with the various dimensions of department output – e.g. quality, timeliness, range, scope, accuracy, reliability, convenience, utility, prices.

Current Mayor’s Management Report

A common feature of reporting agencies in the February 2022 Preliminary Mayor’s Management Report is a section titled “Agency Customer Service.” Under the subheading “Customer Experience” are agency outputs, not customer outcomes.

A few agencies report some form of “customer satisfaction” but I have been unable to locate any discussion in the document or website of the universes sampled, sampling method, dates of conduct, method of contact, number of respondents contacted, question wording and order, or frequency of contact.

***

Douglas Muzzio is a professor of public affairs, Marxe School, Baruch College, CUNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Qualified Immunity is a Jim Crow Relic; For a More Just Future, New York Must End This Harmful Doctrine

Taking stock of history and policy (photo: Paige Polk/Mayoral Photography Office)

In the period following the Civil War, slavery had ended, but the horrors of racial violence persisted. The Ku Klux Klan terrorized newly-emancipated Black Americans with lynching, mob violence, and other vile forms of intimidation and brutality. In response, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1871—also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act—which gave Black Americans the right to file a lawsuit against government officials who engaged in acts of racial assault or who refused to protect them from groups such as the Klan.

But nearly a century later, the Supreme Court set an unjust legal precedent that rolled back these hard-won rights.

In 1967, the Court modified the original act by introducing the doctrine of qualified immunity in the case of Pierson v. Ray, where it was decided that government officials accused of committing constitutional violations are entitled to claim qualified immunity as a defense if they acted “with probable cause in making an arrest under a statute that they believed to be valid.”

And who were the officials at the center of this case, the ones who acted in a way they “believed to be valid?” Police who arrested a group of Freedom Riders protesting racial injustice in segregated Mississippi.

Over the decades, qualified immunity has swelled into a nearly impenetrable legal shield that prevents abusive government officials from facing the consequences for their brutal transgressions. It's now 2022, and victims of state violence continue to be disproportionately people of color. For example, a study conducted by Rutgers University’s School of Criminal Justice reveals that African-Americans are 2.5 times more likely to be killed by police than white people.

The long line of governmental abuse of Black people in this country did not begin with qualified immunity. But this harmful doctrine, a relic of the Jim Crow era, certainly enables it. To create a more just future for all New Yorkers, we must end qualified immunity today.

The good news is, New York can.

Our state legislators in Albany can fix the Supreme Court’s tremendous misstep by passing a bold public safety measure, bill S1991/A4331, that will enable New Yorkers whose constitutional rights have been violated to sue those rogue officials in state court, where the defense of qualified immunity would be prohibited.

Not only is ending qualified immunity the right thing to do, it’s also the popular thing to do: a recent poll revealed that an outright majority of New Yorkers, 58%, favor repealing the doctrine for public officials. State residents from Western New York to Long Island are sending a message that they want policymakers to protect our civil rights and make New York safe for everyone.

It’s important to note that ending qualified immunity is not meant to “punish” cops.

This bill doesn’t zero in on police officers. Rather, the objective here is to give voice to the victims of state violence, to provide a clear pathway to justice for New Yokers whose civil rights have been trampled on by any bad governmental official, not simply law enforcement.

As it stands, the legal system breeds impunity. This has got to stop. We must change the system in order to protect our communities from governmental abuse. As we reflect upon the past, we also renew our commitment to creating a more equitable future. Ending qualified immunity will make New York safe for everyone.

***

Derek Perkinson is the New York State field director and crisis director for the National Action Network, a leading civil rights organization founded in 1991 by the Rev. Al Sharpton. On Twitter @NationalAction.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.