Regulating Live Animal Markets is Key to Protecting Public Health

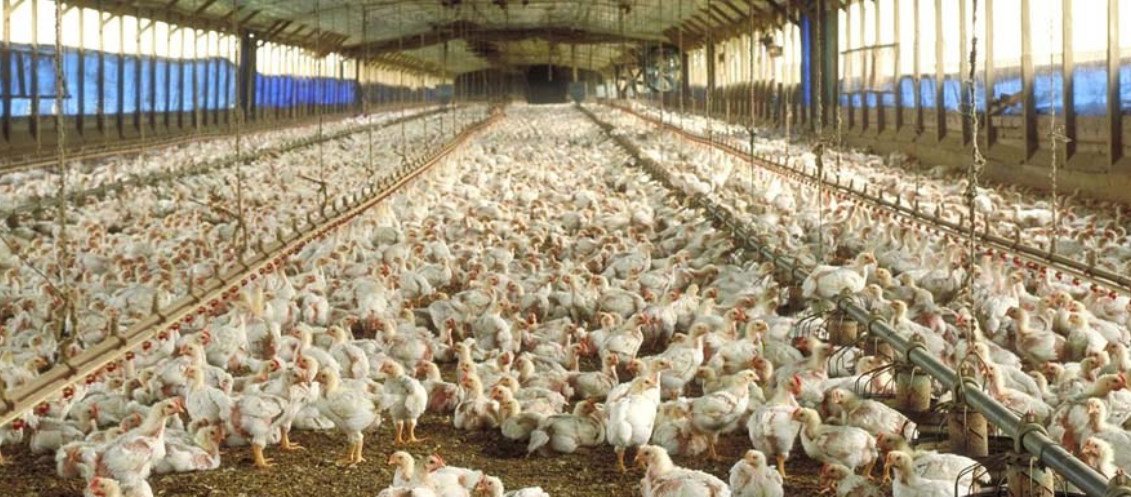

Livestock

It is undeniably the responsibility of governments to protect the public health.

Yet our nation and the world are one year into COVID-19, a devastating pandemic responsible for the deaths of millions of people and the most serious global economic crisis experienced in generations.

The World Health Organization issued a report last week that identifies the COVID-19 virus’ probable origin as animal-based, with bats as the likeliest species, passing the virus to other animals and enabling further spread to humans.

While the rate of infectious diseases originating in wildlife is increasing, there is not a single solution to curbing their spread. I am working with legislators in five other states and the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators (NCEL) on policy approaches so that we can learn from one another on how to better track and prevent wildlife diseases and strengthen our nation's ability to preserve public health.

As we strategize and craft legislation to prevent future devastation from animal-borne viruses and pathogens, we must put firm controls in place to regulate operation of live animal markets. That’s the purpose of my bill in the New York State Assembly, A02054, which would prohibit certain wildlife and fish from being imported into the state in order to protect public health and safety, our native wildlife and fish, and the agricultural inter ests of the state.

Currently, 75% of emerging infectious diseases, such as COVID-19, originate in animals and are known as zoonotic diseases. They include: COVID-19, HIV, malaria, Ebola, SARS, bird flu, swine flu, West Nile and Lyme disease. Almost all of them started with wildlife exploitation through trade or hunting. Here’s how:

Live animal markets bring together wildlife, domestic animals, and humans that might never be in close contact otherwise, and that allows disease to spill over to humans and between species. The reason we’re seeing such a drastic increase in these diseases in recent decades is simple: human activity. Deforestation, wildlife trafficking, and climate change are the primary drivers. In order to prevent the next global pandemic, states must ensure better disease tracking and heightened regulation of the animal trade.

My bill (A02054, with Senate companion S.06047) would amend the environmental conservation law by prohibiting the importation of any individual wildlife or fish species - including bat, rodent, and primate species - that could be responsible for zoonotic transmission of a readily transmissible human disease. This bill, along with continuing to build upon New York’s existing public health and conservation policies, is a critically necessary step for preventing future pandemics.

Additionally, we must protect New York’s incredible natural resources by conserving natural areas that enable natural barriers against disease, and enforce our legislation of wildlife and animal trade protections to decrease exposure to exotic and possibly infected wildlife. Working with scientists and experts, we call for enhanced collaboration between state and federal agencies and higher education institutions to protect public health and safety.

***

Assemblymember Jo Anne Simon represents Brooklyn’s 52nd District. On Twitter @JoAnneSimonBK52.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Can a Long-Shot Candidate Still Win New York’s Mayoral Race?

Mayor de Blasio with Maya Wiley in 2014 (photo: Rob Bennett/Mayor's Office)

How long can pundits wait before they can safely write-off long-shot New York mayoral candidates like Maya Wiley, Kathyrn Garcia, Ray McGuire, Shaun Donovan, or Dianne Morales? The historical answer is: it ain’t over till it’s over. Twice in the last half-century, long-shot candidates ultimately won New York's mayoralty. Ed Koch in 1977 and Bill de Blasio in 2013 each climbed from poll numbers in single digits all the way into Gracie Mansion. And to understand how they did it, it helps to realize that “back-of-the-pack” mayoral wins like Koch’s and de Blasio’s aren’t a phenomenon that’s exclusive to New York City.

Several big U.S. city mayors won after starting from a fourth, fifth, or even ninth position in initial polls, including Miami’s Manny Diaz (first elected 2001), Kansas City’s Sly James (2011), Salt Lake City’s Jackie Biskupski (2015), and Chicago’s Lori Lightfoot (2019). None of these future mayors had more than 5% when they first launched. Other longshots came close. St. Louis Treasurer Tishuara Jones came less than two points of a back-of-the-pack win for mayor in 2017, starting from fourth place with single digit support. (She is now on her second try, hoping to win the St. Louis runoff for mayor on April 6.)

The back-of-the-pack phenomenon crosses borders, too. I’m writing from Canada, where Toronto’s David Miller tied for a distant third place in single digits in early polls before he ultimately defeated four other major candidates in 2003. Both Calgary’s Mayor Naheed Nenshi and Winnipeg’s Mayor Brian Bowman barely registered any support before they surged to win their first runs for office, in 2010 and 2014, respectively. Even the current Mayor of London, England – Sadiq Khan – was a dud in various polls before he began his campaign for Labour’s mayoral nomination in 2015.

If you’re leaning toward a situational explanation for why lightning would strike in the same way so many times, none is obvious. Some of these races were open, but not all. Ed Koch beat an incumbent, Abe Beame, in his primary, as did Biskupski, James, and Diaz in theirs. Having a non-partisan primary helps as a sort of rest-stop for back-of-the-pack candidates on their rise to the top, but it’s not essential; Canadian races don’t have primaries, and yet back-of-the-pack mayoral wins happen there too.

It's easier to point to factors that make mayoral elections distinct from other more traditional partisan races. As New York’s most recent polling shows, the pool of likely but undecided voters tends to stay high for months into a marathon race.. In campaigns to lead cities of millions of people, turnout might only be in the hundreds of thousands, boosting the value of unexpected mobilization and GOTV tactics.

If New York mayoral election pundits are looking for some way to predict whether candidates in single digits can pull off a similar feat in 2021, the good news is that there are some historical patterns to work from. No back-of-the-pack-to-winning campaign is identical to another, but most winners share a combination of similar features. They include:

Hockey-stick support growth. Back-of-the-pack campaigns rarely build support incrementally. Instead, their support simmers up a little before it boils over late in the campaign. In his memoir, Transforming Miami, Diaz described his low polling as “a blessing in disguise…my opponents wrote me off,” while Chicago Sun-Times columnist Mark Brown noted in 2019 that Lightfoot “peaked so late that those other candidates never felt it necessary to train their negative advertising on her.”

A (relatively) positive tone. Studies and memoirs of back-of-the-pack wins almost always emphasize positive messaging. In 1977, even the famously caustic Ed Koch was under orders from his campaign team to avoid quips and sarcasm to project an image of steady competence. Leading with positivity is important, since the end-of-campaign surge usually depends on a growing reservoir of goodwill for the long-shot’s candidacy.

Retail campaigns that prioritize quality engagement. Both the Nenshi and Biskupski campaigns relied on unusually flexible scripts for phone and field canvassers, encouraging volunteers to use open-ended questions to let voters lead the conversation. Nenshi’s “Purple Army” prioritized his time for coffee parties. Koch was constantly accessible on New York streets, while Diaz built early support on foot, door to door, as if he was running for a council seat. Positive word-of-mouth built up over time is critical to scale up at the right moment.

An issue that taps the electorate’s real mood. Almost every back-of-the-pack winner started with - and stuck to - a defining policy issue that was outside the day-to-day consensus on issues at City Hall, but ultimately proved to be a savvier read on what voters wanted to see as a ballot question. For Diaz, it was education. De Blasio famously set himself apart by criticizing stop-and-frisk policing as part of his "tale of two cities" refrain. For Lightfoot, Miller, and Bowman, some variation on ethics policies was decisive, while Koch’s law and order push separated him from a field of more classically liberal Democrats.

Financial stamina. Back-of-the-pack winners aren’t usually the biggest spenders, nor the best fundraisers. Yet| their campaigns never starve, either. In virtually every historical case, candidates relied on a personal network of contributors to maintain steady cash flow through the lean marathon months of their run. It’s not an accident that many such candidates - including Miller, Diaz, Bowman, Khan, Lightfoot, and James, for example - worked for at least a few years as lawyers in private practice.

A distinctive candidate. Almost all back-of-the-pack mayoral hopefuls had some aspect of their personal story that helped them personify political change. Nenshi is North America’s first big-city muslim mayor, Lightfoot and Biskupski became Chicago and Salt Lake City’s first lesbian mayors, and de Blasio’s bi-racial family was front and centre in late-campaign advertising.

A breakout moment. Candidates in single digits inevitably break out and scale up after one or two decisive events at the right instant, bringing the goodwill they’ve built to the attention of unsure voters shopping for better alternatives. Sometimes, it’s an editorial or political endorsement from an unexpected source. Sometimes, it’s a candidate’s attention-grabbing response to a major citywide event, like Koch’s call for a crime crackdown during a mid-campaign blackout. Occasionally, leading candidates take so many hits that it clears a path for the long-shot to step out with a well-timed ad at just the moment when voters are starting to move, as de Blasio did in 2013.

The good news for the long-shots is, it’s still possible. The bad news for them is that they’ll have to keep working, and waiting for luck to strike, to be sure.

The breakout moment often comes very late in the campaign, demanding nerves of steel for the rare few who actually pull it off. In 2013, de Blasio did not top a public poll until August 13th - a mere four weeks before voters confirmed his primary win. Ed Koch polled in fourth place just two weeks before he actually won his bitter primary showdown against future Governor Mario Cuomo. Most of the other mayors mentioned above did not even lead a single public poll before pulling off their respective primary or general election wins. Leading candidates like Andrew Yang, Eric Adams and Scott Stringer will have to keep at least one eye on their rear-view mirror for now, since the breakthrough window for most historic back-of-the-pack wins can be measured in weeks or even days before election day rather than months. And New York’s primary is still more than eleven weeks away.

***

Brian Kelcey is a Canadian writer and consultant specializing in urban politics and policy. On Twitter at @stateofthecity.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Albany Must Aid New Yorkers Washington Left Behind

New Yorkers (photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Governor's Office)

As lawmakers in Albany enter the final days of negotiations on the state budget amidst controversy surrounding the Governor, they must not lose sight of the fact that millions of New Yorkers have been left out of any government aid since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic a year ago – a situation so dire that workers across New York excluded from federal and state aid are partaking in a hunger strike to get the relief they deserve.

For millions of our neighbors there is no rescue plan on the horizon. President Biden’s “American Rescue Plan” will bring much-needed relief to families and unemployed workers across the state struggling to put food on the table, pay rent, and chip away at mounting debt. However, beltway politics mean that the most vulnerable New Yorkers – millions of immigrant workers and children – will again be excluded.

A year after the onset of the pandemic, state leaders have a responsibility to finally step up for households that have been ravaged by the health, economic, and social consequences of COVID-19. Private philanthropy is not large enough to fill the gap of government aid.

By standing up a fund to aid workers excluded from federal assistance and by backing reforms to the state’s child tax credit—the Empire State Child Credit—Governor Cuomo, Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie, Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins, and the Legislature can support those that have suffered the most during this crisis, while investing in our future.

Data from my organization’s Poverty Tracker, a longitudinal study of hardship and poverty among New Yorkers, finds that nearly half of all New York City workers, and more than half of low-wage workers and Black and Latino workers, lost employment income during the height of the outbreak.

According to a report by the New School’s Center for New York City Affairs, since the crisis, more than half of lost jobs were held by foreign-born workers and one in six lost jobs was held by an undocumented worker. Those working in frontline industries are underpaid, with limited ability to social distance, and often lack employer-based health insurance, putting them at greater risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19.

Despite their disproportionate exposure and vulnerability, many immigrant households were excluded from our country’s most powerful COVID-19 relief measure: expanded unemployment insurance benefits in the CARES Act. These benefits, which have kept Americans afloat for the past year, exclude millions of immigrant New Yorkers.

Households with undocumented workers and non-citizens without work authorization were ineligible for expanded unemployment benefits, and households with people who use individual tax identification numbers, or ITINs, were excluded from the stimulus payments that were a centerpiece of the CARES Act.

By excluding the lowest-income and immigrant New Yorkers from these federal policies, millions of New Yorkers are at risk of falling deeper into poverty as the pandemic and economic crisis continue.

Besides immigrant workers, the state’s children have felt profound impacts from the pandemic. Roughly 325,000 children were pushed into poverty since the pandemic began and now over 24% of New York’s children live in poverty.

Lawmakers have the chance to help turn the tide for immigrant workers and their children left out of federal relief, and I commend the Assembly and Senate for proposing $2.1 billion for a fund for excluded workers. Yet these people need more support – lawmakers must establish a $4.6 billion excluded workers’ fund through a bill championed by Senator Jessica Ramos and Assemblymember Carmen De La Rosa to provide financial assistance to workers who have lost income and are ineligible for unemployment insurance. This New York fund would provide unemployment assistance payments to previously excluded New Yorkers: undocumented workers and formerly incarcerated individuals, retroactive to April 1, 2020 through the end of 2021.

The second action would be reforming New York’s Empire State Child Tax Credit along the lines of legislation proposed by Assemblymember Andrew Hevesi. The bill would expand the credit to children living in deep poverty by providing an enhanced maximum credit of $1,000 for children under age 4, and would increase the maximum available credit to $500 for children ages 4 to 16. Congress is on the cusp on enacting a one-year expansion to the federal child tax credit, but many children would still be excluded from its impact.

The Hevesi bill would provide immediate relief to at least 70,000 excluded children and would benefit 2.1 million New York families once fully phased in. Estimates show it would reduce child poverty by nearly 8%, deep child poverty by 9%, and under-4 child poverty by 12%. This would amount to the most significant reductions in the state’s child poverty rate in decades.

Columbia University researchers have estimated that child poverty costs New York over $60 billion a year. Cost-benefit analyses of expanding child tax credits to the poorest and youngest children have shown societal returns of up to $8 for every $1 spent on these programs.

Child poverty and the continued exploitation of immigrant workers is a stain on the state’s progressive credentials. Our leaders in Albany can end the pattern of neglect and issue a long-overdue dividend for children in poverty and excluded workers instead of continuing to mortgage our future.

***

Wes Moore is the Chief Executive Officer of the Robin Hood foundation, which has granted more than $71 million since the onset of the pandemic to organizations assisting New Yorkers. On Twitter @iamwesmoore & @RobinHoodNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.