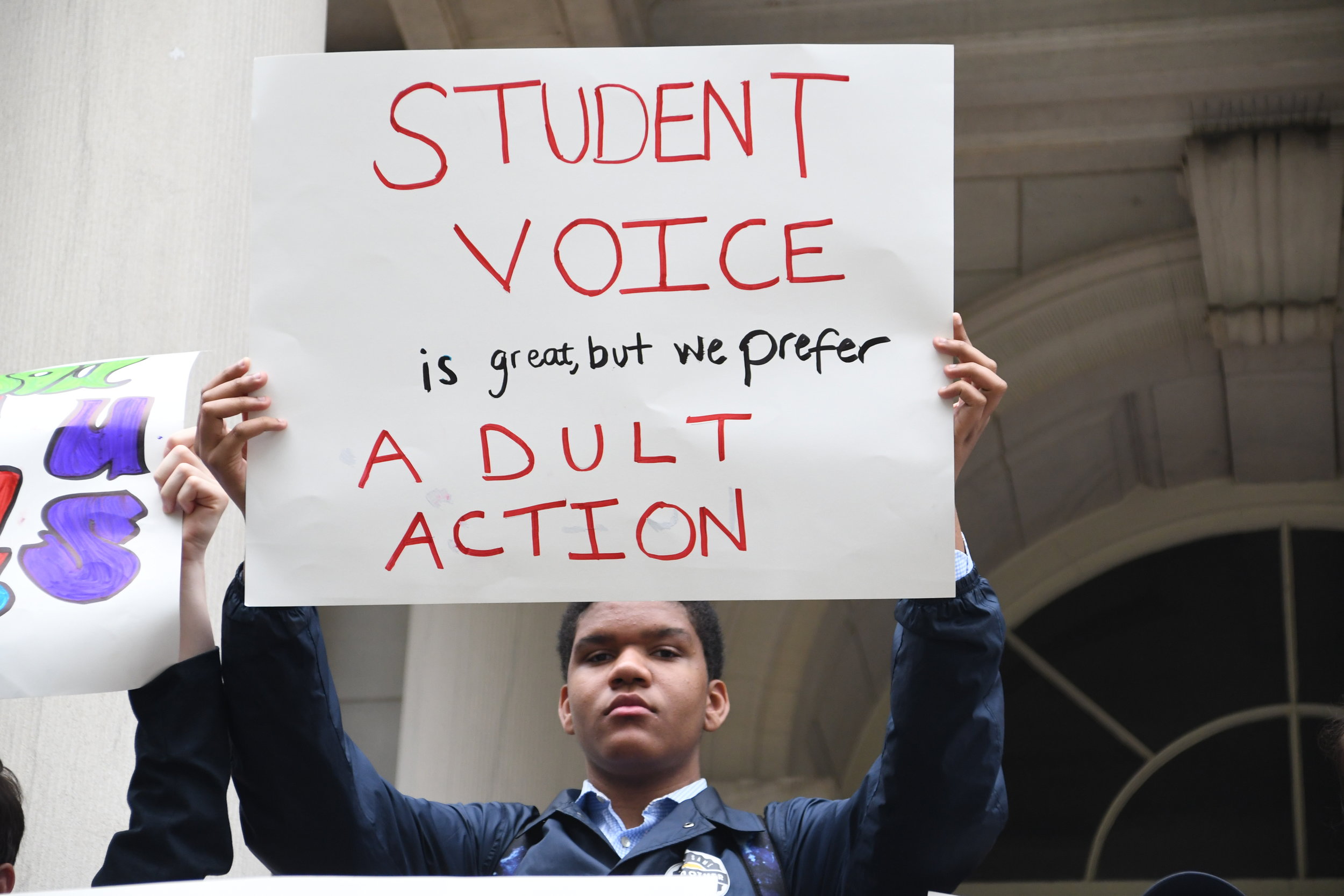

Brandon St. Luce, the author (photo: Dulce Michelle)

Sunday, May 17 of this year, marked 66 years since the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that “separate is inherently unequal.” Yet today, many of our nation’s public school systems remain both separate and unequal. Nowhere is this clearer than in New York City, where I attend high school.

For five years, Mayor Bill de Blasio has touted an “Equity and Excellence” agenda while maintaining discriminatory admissions requirements at hundreds of middle and high schools that exacerbate segregation and inequity.

While these admissions requirements, known as “screens,” are not new, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has confirmed their unfairness, with nearly a third of public school students not having access to a laptop or reliable internet access, both essential during remote learning and for any student who wants to do the out of school preparation necessary for getting into the most competitive screened programs in the city. It has also given us a chance to hit the reset button. Many of the metrics that selective schools have traditionally used to sort applicants will not exist for the cohort of students applying to middle and high schools in December.

Screens vary from school to school, but screened schools have a long menu of options to choose from. They can restrict admission based on a host of factors, including, but not limited to: grades, attendance, punctuality, state test scores, zip codes, portfolio assessments, interviews, auditions, and school-administered specialty exams.

No, I’m not just referring to the city’s eight specialized high schools, for which the state legislature controls admission to the largest three. I’m talking about hundreds of screened schools squarely under the jurisdiction of Mayor de Blasio and the New York City Department of Education.

Admissions screens, which use flawed measures of “merit” to sort students, wind up segregating us by race and class. System-wide, two-thirds of students are Black or Latino and about 75% are poor. But at 30 of the most intensely screened public high schools, only one-third of students are Black or Latino and just 40% are poor. The effect is undeniable.

For more than two years, my peers and I at Teens Take Charge have been calling for integration through the removal of these admissions screens. We have proposed alternative policies in meetings with city DOE leaders, including Chancellor Richard Carranza and his cabinet of deputies.

Throughout the last two years, we have run two campaigns, both centered around the idea of abolishing admissions screens. Starting with the Enrollment Equity Plan, we proposed creating thresholds in all schools to make sure that at least 25% and no more than 75% of each high school's incoming freshman class has passed middle school state tests. This year we began to advocate for an “educational option” (ed-opt) model of admitting students in every school. This is not a new model, and it has been proven to help schools accept a diverse pool of applicants, including in my school, Edward R. Murrow High School, which is the most diverse school in the city. We have research that shows how much this would help with the demographic disparities in schools, backed up by the DOE’s own data.

We have led rallies, sit-ins, and, most recently, weekly “strikes for integration” at school campuses across the city. These strikes got major news coverage and turned out nearly 2,000 students from more than a dozen schools, including Beacon, NYC Lab School, and Millennium Brooklyn, three of the most heavily screened high schools in the city.

Every city and school official we have spoken to has acknowledged that screens contribute to segregation in our schools. They thank us for our advocacy. They tell us they are working on a solution. But nothing changes. The only high-ranking official who has not met with us or responded to our proposals directly is Mayor de Blasio, who we believe has been the primary obstacle to removing screens.

He didn’t even respond to his own School Diversity Advisory Group’s recommendations last year to end all middle school screens, some high school screens, and the ridiculous Gifted-and-Talented exam for four-year-olds. In September, he claimed that he would spend this school year doing public engagement on the recommendations, but there has yet to be a single public engagement opportunity.

This school year has come to an end, with the latter part being spent online with varying degrees of success, and it is irrational and illogical why screens should exist for students applying to schools next year. The only reasonable solution for next year is to forgo screens altogether and allow student choice to be the number one factor that guides where students are matched.

When demand for a school is greater than the number of seats, applicants could be matched using an equitable method called educational option (“ed-opt”) that is already in use at hundreds of city high schools. This system admits a proportional number of students who are below, at, and above grade level, producing academic diversity — which often translates to racial and socioeconomic diversity as well.

Proponents of screens and competition, namely, the Parent Leaders for Accelerated Curriculum and Education (PLACE), argue that screens are fair, bias-free assessments of hard work. As a student who recently took the Advanced Placement exam for U.S. History, I see a correlation in the way PLACE leaders talk about admissions screens and the way white folks in the Jim Crow South talked about literacy tests and poll taxes.

Low-income students and other vulnerable student populations are inherently punished by screens. Up until the pandemic, hundreds of thousands of New York City students did not have laptops or home WiFi, yet the high school admissions process has shifted entirely online and many screened schools require students to submit information or assignments online.

Then there are students like Jude, a 13-year-old at “one of the most competitive middle schools in the city” who recently started a petition to preserve the use of screens. Featured in a New York Post article, he is described as a “longtime Kweller Prep student.” Kweller Prep is a private tutoring company that charges thousands of dollars for its services, which include helping middle schoolers get into screened and specialized high schools. I’m sure Jude is a hard worker, but so are the thousands of other students across the city who cannot afford private tutoring.

To be sure, students like Jude and the parent leaders of PLACE are not our opponents. They are simply playing by the rules that Mayor de Blasio sets. And for far too long, those rules have allowed privileged students to cluster in a relatively small number of schools, bringing their social capital, PTA donations, and political savvy with them.

At a recent briefing, Chancellor Carranza gave us reason for optimism when he stated, in response to a question about next year’s admissions, that he and the mayor “will not penalize students in any way, shape, or form because of circumstances out of their control.” That’s exactly what screens do: penalize students for things outside of their control.

On April 16 of this year, Caranza also stated he would not allow “anyone to say ‘when we go back to the normal,' because the normal was never good enough for our kids. The normal meant some were privileged some were not.” The problems with screens have been identified by those who can create monumental change, yet their policies continue to benefit the most privileged in the city.

In the wake of this pandemic, Mayor de Blasio, Chancellor Carranza, and the Department of Education have an opportunity to shed New York City’s distinction as one of the nation’s most segregated school systems. This is the moment to start building the fair, integrated school system that was promised to us 66 years ago -- a system that gives every student the opportunity to thrive.

***

Brandon St. Luce is a junior at Edward R. Murrow High School in Brooklyn and co-leader of the policy team at Teens Take Charge, a student-led organization that advocates for educational equity in New York City schools. On Twitter @TeensTakeCharge.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.