A Fall Agenda for the City Council Veterans Committee

CM Ulrich presents veteran Robinson Arana with a proclamation (photo: @eric_ulrich)

A year ago I wrote a column on issues the New York City Council Veterans Committee should consider holding hearings to address. It was an ambitious agenda, and many in the veterans community were still in a honeymoon phase with the newly structured committee and weren’t sure what to fully expect.

However, under the leadership of the chair, Council Member Eric Ulrich, the committee continued its serious and straightforward approach toward issues of importance to the city’s military veterans. This resulted in not only renewed optimism and increased participation from the community, it led to a number of bills signed into law and saw a city budget for the new 2016 fiscal year that contains an additional $2.9 million toward veteran services.

As we rapidly approach the Council committee’s first fall hearing this week, it’s time again to set a fall agenda. Suggestions, in no particular order:

Veterans Legal Task Force: With the creation of Veterans Courts across the country over the past decade, one of the major problems in the city has been the disparity of how veterans are treated in the criminal justice system depending on what borough they live in or where they happen to be arrested. This is a major issue, especially in Manhattan – the only borough that currently doesn’t have a Veterans Court.

Last February, the Veterans Committee, along with the Committee on Courts and Legal Services, held an oversight hearing on Veterans Treatment Courts. As a result, Council Members Ulrich and Rory Lancman proposed legislation calling for the creation of a Veterans Legal Task Force to study veterans’ access to legal services and resources within the city’s criminal justice system. That bill (Intro. 793) is scheduled to be the focus of the committee’s first hearing on Friday and is an excellent topic to start the new legislative session.

Mental Health: In May and June the committee held hearings that touched upon mental health issues. In both instances, Commissioner Loree Sutton, head of the Mayor’s Office of Veterans Affairs, highlighted MOVA’s partnership with New York City First Lady Chirlane McCray, who over the past several months has been meeting with city service providers, non-profit organizations, and advocates in preparation to unveil her “mental health roadmap” sometime this fall.

As part of those meetings, the First Lady visited local VA hospitals, met with veteran advocates in the arts space, and sat down with the wives of senior military officials during Fleet Week. The administration has not been forthcoming on what the roadmap may look like for veterans and the community awaits its release this fall. When the report is unveiled, the Council committee should consider holding a hearing with city agencies, non-profits, veteran service organizations, and mental health advocates to discuss how feasible the plan is and if there are any areas for veterans that can be improved upon.

[Related: McCray Set to Unveil 'Mental Health Roadmap,' Signature De Blasio Plan]

Veteran Homelessness: During his January State of the City address, Mayor de Blasio promised to end veteran homelessness in New York City by the end of the year. This was an ambitious goal, but as of July the City appeared to be on track to reach it.

Unfortunately, a recent New York Daily News report states that it is now unlikely veteran homelessness in the city will be ended this year - but it should be acknowledged that huge gains have been made toward reaching “functional zero.” In 2013, there were 3,000 veterans in shelters and over 300 on the streets. Today, there are roughly 950 veterans in shelters and fewer than 20 on the streets. That is a precipitous drop by any measure.

The committee has not had a hearing on homeless veterans since November of 2011 and this would be an opportune time to hear from the administration regarding what steps it’s taking to get to functional zero; how it's working with the VA; and to solicit thoughts and ideas from non-profits, advocates, and the public.

Veteran Vendors: It’s been thirty-four years since the city capped the number of street-vending permits, creating a black market that allows permit holders, some whom don’t even reside in the city, to renew them every two years at regulated prices and then rent them out for much higher prices to vendors who then masquerade as independent contractors.

Recently, the City reduced the amounts on some fines, however, disputes between street vendors, BIDs, and brick-and-mortar businesses has made vending inefficient and sometimes dangerous. After years of complaining from all sides, Crain's New York Business reported that there is a move in the City Council to create legislation that will address these issues.

When this legislation is finally introduced (presumably this fall), military veterans who are vendors will also need to have their voices heard regarding how the legislation will affect them. Therefore, the committee should consider holding a joint hearing with the Consumer Affairs Committee to solicit input and feedback from veterans on this legislation.

Intro. 314: Last September Council Member Ulrich held a hearing on Intro. 314 - a bill that would change the Mayor’s Office of Veterans Affairs (MOVA) into a separate department, outside of the mayor’s office but still under the mayor’s purview. This bill would expand the office's capabilities while also making it easier for Council members to obtain funding for local veteran providers in the boroughs directly through MOVA, instead of through other city agencies that are unfamiliar with these groups.

Currently, the legislation has enough votes to make it out of committee and then, in all likelihood, the full Council. However, there must first be compromise between the de Blasio administration and the Council as this bill would require many changes regarding oversight, budgeting, mission, and even place in the City Charter. Nevertheless, this is an important piece of legislation for the veterans community and a follow-up hearing and vote to finally move it out of committee should be held.

Lastly, the committee should consider follow-up hearings with the city Department of Small Business Services on its report recommendations and progress on a pilot program regarding city contracts for veteran-owned businesses; as well as a hearing on veterans and legal issues such as Family and Housing Courts.

Like last year, I am recommending a fairly hefty agenda and it won’t all happen this month. However, if Council Member Ulrich and committee members continue to approach veterans issues with the due diligence they’ve shown over the past year; the coming months will be as successful as the past year. I look forward to following and participating in the committee’s work.

***

Joe Bello served 11 years in the U.S. Navy/Naval Reserve and has been a veteran’s advocate in New York City for two decades. He is a member of the City’s Veterans Advisory Board and the founder of NY MetroVets.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

In New York, Workers Have Earned a Better Life

Labor Day was created to pay tribute to America's hard-working men and women, but for many working and middle class families in New York City and elsewhere, taking time off during the holiday is not an option. For too many Americans, Labor Day is just another work day as they face their realities and see their challenges only grow.

Across our state, countless hard-working New Yorkers, who help to feed, serve, clothe, and build this country still struggle like never before in low-paying full- or part-time jobs. Nationally, wages have not kept up with inflation. In New York the minimum wage is just $8.75 an hour.

Erratic work schedules are becoming the norm, especially for workers in the service sector, like those at Walmart and McDonald's. This kind of scheduling makes it all but impossible for workers to control their lives, let alone go to school or take care of a child or a loved one.

Even worse, as Bloomberg News just reported, irresponsible companies like Walmart promise to raise wages, and then turn around and cut hours—so workers actually earn less. And, to add insult to injury, trade deals supported by Democrats and Republicans offer false promises of better jobs, but we continue to see good New York jobs shipped overseas.

As a result, income inequality has risen to levels not seen since the 1920s and the divide between the rich and poor continues to grow. According to the new book "$2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America," the number of U.S. residents struggling in poverty and trying to get by on only $2.00 a day has more than doubled since 1996.

This Labor Day, every New Yorker must ask themselves: how long can this nation endure when so few have so much, and so many have so little?

For the sake of all of our families, this must change. And that change must begin now.

From Montauk, Long Island to Buffalo, our strong union family is more determined than ever to fight for a better life for 75,000 all hard-working UFCW members. Our message to every worker is a simple one: you've earned a better life.

Every day, not just on Labor Day, unions work hard to provide the better wages, benefits, and protections that working men and women truly need. The results and benefits of joining a union are quite clear. On average, nationally speaking, union workers earn 27 percent more than non-union workers, and are more likely to have paid sick leave and a pension plan.

More importantly, it is clearer every day that our nation's broken political system is unlikely to address income inequality, and poor wages and benefits will not be addressed by irresponsible companies more interested in PR stunts.

Real change will come from hard-working people joining together to fight for it.

That's what Labor Day must be about.

Labor Day should be a day where hard-working people join together to demand a better life. It must be a day where workers, whether working at Wegmans or Walmart, say enough is enough and call for better wages, better benefits, and a better life they deserve.

But above all, Labor Day must also be when New Yorkers realize that there is no corporate hero coming to the rescue. Instead, hard-working men and women must seize the opportunity to define their own destiny.

Doing so begins with every worker knowing that they have power, with our help, to negotiate a better life for themselves and their family. When all is said and done, no one in New York should have to fight for a better life alone.

***

Ed Lynch is the Special Assistant to the Region 1 Director, UFCW International Union in New York City.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

In Defense of Plazas, from Times Square to Brownsville

Diversity Plaza in Jackson Heights, Queens (@NPPNYC)

Police Commissioner Bratton's suggestion to remove the Times Square plazas in order to rid them of desnudas is not just about the future of one of the world's best public spaces. This regressive response could undermine a policy that has transformed New York's public realm.

Pedestrian plazas are an inexpensive, effective way to advance Mayor de Blasio's agenda for a more equitable city, addressing the essential tenets of his admirable OneNYC Plan. They improve public safety, promote health and wellness, cultivate arts and culture, create new open space (30 acres so far), and generate economic activity. Miles away from the crowds on 42nd Street, dozens of New York City neighborhoods have embraced their plazas and the civic benefits they deliver.

For every aggressive Elmo at Times Square there are a dozen children playing hide-and-seek among plaza planters in Corona; yoga classes in Brownsville; families reading together in Ozone Park; thousands of immigrants celebrating holidays in Jackson Heights; and the regulars playing chess in Clinton Hill.

More than 70 neighborhood plazas give people much-needed places to relax, meet with friends, eat lunch, or simply find a seat. Nearly half of those plazas are located in the city's densest neighborhoods, where parks and spaces for community events are scarce.

These plazas, including those at Times Square, are inherently different from both the pedestrian malls of the 1970s and the "privately owned public spaces" made possible by a 1961 zoning amendment and which proliferated in Manhattan in the 1980s and '90s.

The Department of Transportation (DOT) Plaza Program is consciously designed to address the challenges posed by those earlier models, by giving local organizations management responsibility. These new plazas reclaim streets for and with community input. Local non-profits take on the responsibility of managing the plazas, from programming to keep the space active to full-on maintenance. This gives them a decidedly community character, reflected in each plaza's daily rhythms and formal events.

New York's neighborhood plazas are the 21st century expression of Jane Jacobs' "sidewalk ballet," now playing out in streets reclaimed by citizen activists.

It is telling to remember that in 2009 when the DOT took the radical step of closing swaths of Broadway to vehicles, there was much hue and cry about the ruin of Times Square. That spring the streets were painted closed, and as a stop-gap measure while furniture was on order, the Times Square Alliance bought 600 lawn chairs and put them on the street. Two things happened right away: droves of people sat in them; and the lawn chair became a new symbol of Times Squares - loved and hated in equal measure.

There was pent-up demand for this kind of space, and the public conversation went straight to what kind of chairs the plaza should have, drowning out the debate over whether or not the street should be closed to cars. Now, seven years later, this backlash against the mayor's considered solution to the desnudas is clear: New Yorkers and tourists alike love their plazas.

Neighborhood plazas, especially those in high-need areas, are facing their own quality of life challenges, as well as significant financial stress in managing their upkeep. The Times Square controversy has ignited a long-overdue public conversation about our collective vision for public space and the equity issues it raises.

These problems are solvable. They simply require some new thinking about how to manage a new asset. We owe it to every neighborhood, and to the millions of New Yorkers enjoying this network of urban commons, to address these issues without undermining one of the city's most progressive amenities.

***

by City Council Members Daniel Dromm and Brad Lander, and Laura Hansen, Managing Director, Neighborhood Plaza Partnership/The Horticultural Society of New York

Dromm is the New York City Council Member, District 25, home to Diversity Plaza

Lander is the New York City Council Member, District 39, home to Kensington Plaza

Laura Hansen is Managing Director, Neighborhood Plaza Partnership/The Horticultural Society of New York

Hudson River Rail Tunnel Discussions Recall Checkered History of Federal Aid to New York

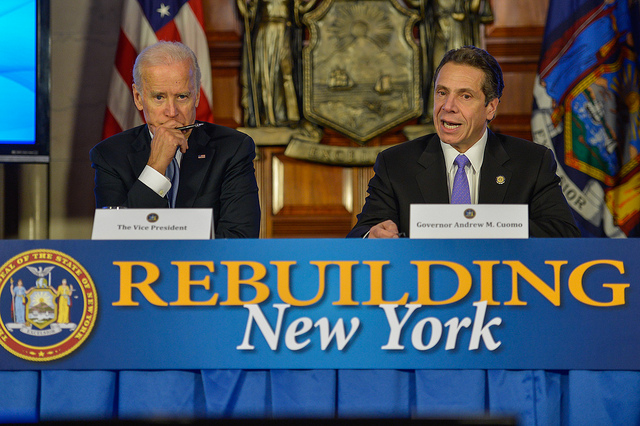

Gov. Cuomo & VP Biden (photo via the governor's office on flickr)

New Jersey officials met with U.S. Secretary of Transportation Anthony Foxx on August 18 to discuss strategies for building new rail tunnels under the Hudson River between New Jersey and New York. The existing tunnels, over a century old, were damaged by Superstorm Sandy in 2012 and recently experienced electrical failures and train delays.

Governor Andrew Cuomo has been pressuring the federal government to pay what he refers to as "the lion's share" of the costs for the new tunnels. It isn't clear whether Cuomo wasn't invited or chose not to attend the August 18 meeting. He had told reporters a week earlier that any meeting would be premature until Washington committed to a sizeable investment in the project. "There's no reason to meet now," he said snappishly. "They need to put their money where their mouth is."

After the meeting, the heated rhetoric cooled a bit. In a statement on August 19, Cuomo hailed the meeting as a step in the right direction but reiterated "I strongly support the construction of the new Hudson River tunnel – and a federal grant package that makes the project viable is an essential first step." A spokesman for Secretary Foxx responded that "As the governor knows, the federal government doesn't just issue grants without a fully defined scope, project, and applicant and at the present time there isn't a fully defined project or applicant we can even grant money to."

We can hope that the tone of the dialogue will continue to get more positive and New York, New Jersey, and federal officials will get down to concrete negotiations. The need is critical and, as Cuomo has pointed out, there have been many inconclusive meetings over the years to address it.

But looking back through history, federal aid to big New York projects has been an inconsistent story.

In the early 19th century, New York sought federal aid to build a cross-state canal. A delegation of New Yorkers lobbying Congress in 1812 found little support and noted resentment that "the envied state of New York" was "a supplicant for the favor and a dependent on the generosity of" the federal government rather than using its own resources. Five years later, partial funding was included in a bill that passed Congress, only to be vetoed by President James Madison. He found no authorization in the Constitution for federal support for "watercourses," the president said. Canal advocate DeWitt Clinton, the Mayor of New York City, described the veto message as "a miserable sophism...reprehensible conduct" motivated by sectional rivalry and "jealousy of the growing prosperity of New York."

A resentful New York stopped asking for U.S. assistance. Clinton was elected governor in 1817, and the state built the Erie Canal with its own resources.

In 1975, New York City was on the verge of bankruptcy due to overspending, financial mismanagement, and banks' unwillingness to provide additional loans to the city. Gov. Hugh Carey established the Municipal Assistance Corporation and an Emergency Financial Control Board to oversee the city's budget and provide investors with assurance that funds lent to the city would be repaid.

To obtain additional needed funding, the city sought a federal guarantee of its securities. President Gerald Ford, who was critical of the city's profligate spending, refused to consider what he termed a "bailout." That led to a now-famous New York Daily News headline on Oct. 30, 1975: "FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD."

Ford did not actually utter those words but he believed his stern position would help force New York City to mend its fiscal management. An indignant Carey complained in a speech a few days later that "it isn't fair when the President of the United States hauls off and kicks the people of the City of New York in the groin." But the next year, as state oversight and city budget reductions began to improve the situation, Ford declared that New York had "bailed out itself." He agreed to federal loans to the city.

Carey learned from the process. In 1979, when the state was desperately seeking resources to aid in the cleanup of the Love Canal area in Niagara Falls, the governor persuaded president Carter to declare the area a federal disaster area, which freed up modest federal resources. The next year, a confidential study of the toxic site by the federal Environmental Protection Agency was leaked to the New York Times. It reported alarming evidence of cancer and chromosome damage. Hooker Chemical, which had dumped toxic chemicals in the abandoned canal, covered them over, and then sold the land to unsuspecting purchasers, was the main culprit. At about the same time as the EPA study, though, reports surfaced that the Army had dumped chemicals at the site during World War II. The Defense department denied it, but it provided just a whiff of federal culpability.

Carey saw an opportunity: use the report to renew pressure on the federal government to pay for relocation of residents who were panicked by the EPA report's alarmist message. "Permanent relocation away from the contaminated area is the only reasonable way to deal with the trauma being experienced by area residents," he told the press. It was a neat political pivot, directing attention away from the state's response to the crisis and toward President Jimmy Carter.

Politics played in New York's favor. Carter, running for reelection in 1980 and trailing challenger Ronald Reagan, needed the Empire State's votes. In October of that year, he flew to Niagara Falls to sign legislation authorizing massive federal aid to supplement state resources to relocate residents and contain the toxic chemicals. (Carter carried Niagara County in the election but lost New York and the election to Reagan.)

The projected price tag for the Hudson tunnel work -- $14 billion -- is itself evidence of the need for federal help. New York officials are on something of a roll, having secured federal aid for the cleanup after Sandy and assistance in the construction of the new Tappan Zee bridge. This time, New Jersey will be an ally and a partner, and it can be argued that the tunnels are critical corridors in the nation's transportation infrastructure.

History suggests, however, that politics and perception are always factors when it comes to federal assistance to New York. Arguably the nation's historically most significant state, and given to assertive self-confidence, New York is often regarded by outsiders as being able to take care of itself. Usually, it can. But other times -- and the Hudson River tunnel is a good example -- we can legitimately ask for federal assistance.

***

Dr. Bruce W. Dearstyne is the author of the book The Spirit of New York: Defining Events in the Empire State's History, published in 2015 by SUNY Press.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Put Queens Residents First in Willets Point Development

FC Queens community meeting

For decades, the Willets Point area in Queens has loomed large in the daydreams of real estate developers and city planners. Redevelopment plans for this neighborhood of mechanic shops and other small businesses have been floated for decades, but none have come to fruition.

Now that the city has all but abandoned a fatally flawed Bloomberg-era plan for the area, a new plan for cleaning up Willets Point is still needed, but it must better address the needs of the low-income and working-class Queens community in which it's located. There are several specific ways in which this goal must be realized.

Several years ago, the Bloomberg administration made a deal with Related Companies and Sterling Equities to redevelop Willets Point to yield the developers enormous profits, but with little commitment to build affordable housing. But a court ruled against the development, because it would have unlawfully allowed a shopping mall to be built upon part of Flushing Meadows-Corona Park.

Mayor de Blasio's administration recently decided not to join the developer in appealing a judge's decision to ban the mall's construction without real concessions from the developer toward meeting the community's needs through affordable housing development.

As the Fairness Coalition of Queens (FC Queens) has been arguing for years now, the last thing that Queens needs is another mall. What the Queens residents in the area do need, and deserve, is the following.

First and foremost, Willets Point needs to be cleaned up. The site has been highly contaminated for more than a century. Now that the city has spent millions displacing dozens of vibrant small businesses from the area, it's at least time to remove the toxins from our communities' backyard.

Second, as affordable housing becomes ever more scarce in Queens, it's vital that Willets Point be used to build truly affordable housing—with a substantial proportion of units that are affordable to the many local residents earning 20 to 30 percent of Area Median Income.

Third, with jobs so hard to come by for local Queens residents, the Willets Point development must ensure that local residents are granted hiring preferences, with strong training and apprenticeship programs to provide career pathways for local workers.

Fourth, whoever ultimately develops Willets Point should be required to contribute significantly to the Flushing Meadows-Corona Park Conservancy and be partners in improving the park to better serve Queens residents.

Finally, the community must be deeply involved throughout the planning process. FC Queens, an umbrella group of dozens of faith, immigrant, housing, and youth-serving agencies, has been at the forefront of preserving open space and expanding affordable housing. The administration and its chosen developers need to engage our stakeholders in this process to ensure that the next plan for Willets Point is one that actually works for Queens residents.

We all want a bright, new future for Willets Point, but it must be a plan that puts the needs of Queens residents first. Otherwise, the history of failed development plans for this prized Queens site will continue to repeat itself.

***

Javier H. Valdés is the Co-Executive Director of Make the Road New York, the largest grassroots community organization in New York offering services and organizing the immigrant community, and a member of the Fairness Coalition of Queens. On Twitter: @maketheroadny.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Bill Puts City Landmarks Law At Serious Risk

SoHo-Cast Iron Historic District (photo: @GVSHP)

This year’s 50th anniversary of New York’s landmarks law is a good time to take stock of how much our city has benefitted from preservation. And, as we do so and acknowledge the importance of preserving key elements of New York’s history and appeal, we must be careful not to let our guard down.

Landmarked buildings and neighborhoods, many of which were once blighted and neglected, now nearly without exception brim with new investment and pride. Landmarking somehow manages the dual feat of promoting economic development while, with its anti-demolition protections, helping long-time residents and businesses stay put if they wish to reap the benefits of the increased appeal of their surroundings. Preservation has clearly been a key ingredient in New York’s renaissance over the last several decades.

Unfortunately, a bill with a serious chance of passage scheduled to be heard at the City Council on September 9 would change much of that. Intro. 775 would for the first time impose ‘do-or-die’ timeframes for buildings and neighborhoods being considered for landmark designation. If the deadlines are not met, buildings and neighborhoods, no matter how worthy or endangered, would automatically be disqualified for designation. Reconsideration would be prohibited for a period of five years, during which time demolition could proceed unhindered.

Had the bill’s draconian provisions been in effect over the last fifty years, more than half of our city’s landmarks and historic districts would not have been designated, since those designations took longer than the bill allows. Given that a significant number of owners of those properties originally resisted designation (though many later came to appreciate the benefits of landmarking), the bill’s five-year greenlight for demolition would have no doubt meant many beloved landmarks would have been lost.

Landmarked neighborhoods that took longer to designate than the bill requires include Greenwich Village and the Grand Concourse; Bedford Stuyvesant and Boerum Hill; Jackson Heights, Hamilton Heights (Sugar Hill), and the South Street Seaport, among many others. The Empire State Building, Rockefeller Center, Grand Central Terminal, and the Woolworth Building all also failed to meet the rigid deadlines Intro. 775 would impose.

The purported purpose of the bill is to prevent sites under consideration for landmark designation from staying in limbo indefinitely without a final vote. Right now there are 95 such sites in New York City that have waited over five years without a final determination on landmark status – less than 0.3% of all the buildings ever considered for landmark designation in New York City. By contrast, the problem Intro. 775 would create, represented by the more than 17,000 worthy landmarked structures which would have been disqualified for designation under the bill’s provisions, would be more than 170 times the size.

(It should be noted that the Landmarks Preservation Commission has agreed to vote upon the 95 undesignated sites within the next 18 months, essentially eliminating the bill’s entire raison d’etre.)

Ironically, Intro. 775 would do nothing to address the actual reasons why some landmark designations take considerable time. Those which run the longest typically are the most controversial or complicated, involving delicate negotiations with stakeholders, careful examination of final boundaries, exhaustingly-detailed research to back up the Commission’s conclusions, and meticulously detailed designation reports to aid owners in understanding the implications and parameters of designation. To meet these needs, the bill would provide no additional resources to the Commission, the smallest of New York City’s over 100 city agencies, in spite of its considerable mandate to regulate more than 33,000 landmarked properties and evaluate the historic resources of the entire city.

Rather than encouraging smooth and timely decision-making, the bill would actually encourage delaying tactics and obstructionism by powerful developers opposed to landmarking, by offering the option of “running out the clock.”

Intro. 775 would also have a chilling effect upon the Commission, which no doubt would avoid controversial or complicated designations so as not to squander its limited resources on proposals which might take longer than the tight, legally-mandated timeframes would allow. Many have wondered if this is the true purpose of the bill; Intro. 775 is backed strongly by the Real Estate Board of New York, which has opposed nearly every landmark or historic district designation in New York City, and made a top priority of gutting the landmarks law.

The City Council has much less onerous ways which it rarely uses to encourage the Landmarks Preservation Commission to act as it deems appropriate.

Not only does the Council control the Commission’s purse strings, but it must approve the appointment of every Commissioner to the body, including the Chair, who decides when designations take place. Rather than exercising such reasonable oversight, through Intro. 775 the City Council would pretend to address a complex issue by simply tying one of the agency’s arms behind its back, while giving greater leverage and advantage to one of our city’s already most powerful and influential interest groups.

To address what is at most a tiny issue which appears to be already resolved, Intro. 775 throws the baby out with the bathwater – in this case, New York’s architectural and cultural heritage.

And, it is not a slow-moving municipal bureaucracy that will suffer for it, but our city’s rich multi-layered history, diverse neighborhoods, and iconic landmarks.

***

Andrew Berman is the Executive Director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation

****

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Cuomo and De Blasio Must Do More to Fight Homelessness

Gov. Cuomo (photo via the governor's office on flickr)

New York City's homelessness crisis has blemished Mayor de Blasio's progressive track record, and rightfully so. While Mayor Bloomberg made our city the capital of homelessness in the United States, Mayor de Blasio, now in his second year, must take responsibility and meaningfully address the problem.

Although the reduction in shelter numbers from 60,000 to 56,000 is certainly progress, it is woefully far from a bold vision for "ending the tale of two cities" and ensuring access to truly affordable housing for poor and low-income New Yorkers.

But to be fair, it's hard for the mayor to have a bold vision when the governor blocks him at every turn.

Governor Cuomo has refused to fully fund homelessness services, or even work with New York City to make existing public assistance and shelter programs to house the homeless more effective. Instead, the governor has used the homelessness crisis as a political opportunity to slam the mayor, while his own office continues to worsen the problem.

In fact, Governor Cuomo's recent rhetoric invoking the reemergence of the "bad old days" when discussing Times Square is actually a reflection of his own political decision to not fully fund supportive housing in his last budget or meaningfully reform laughably low public assistance shelter grants.

The governor has also refused to contribute state dollars to innovative housing subsidy programs developed by the city's Human Resources Administration (HRA), leaving the city to foot the entire bill, thus limiting its reach. As a result, New York's homeless and people who are nearly homeless, including those in need of mental, physical, and behavioral health services are left with no option other than the streets.

The reality is that both Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo should be doing more to address the city's record homelessness. Advocates and public policy experts have shown them solutions that they both have yet to adopt. Instead our mayor and governor have opted for political expediency over good public policy and finger-pointing over asserting leadership.

Mayor de Blasio must demand more dedicated housing for the homeless from developers reaping massive profits through tax subsidies and land deals. This could be accomplished if New York City's Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) required a baseline of 10 percent of units to be set aside for the homeless for development projects that benefit from public resources. The developers would still make staggering profits and the city could remedy the scarcity of affordable housing units by not giving away land and money to wealthy developers that get rich off gentrification and displacement. The city should also require current developments and NYCHA to commit many more existing units to house homeless New Yorkers.

On the state level, Governor Cuomo must fully fund supportive housing, known as the NY/NY IV agreement, and work with city agencies to make homeless housing vouchers, funded by both the city and state, as effective and well-resourced as possible.

There is little doubt that the Governor could get the necessary funding for supportive housing in his upcoming budget (of course, getting the job done last year would have been better), and his own state agencies already have the power to work more effectively with city agencies if they were directed to do so.

Governor Cuomo's task is far easier than Mayor de Blasio's – which is all the more reason to characterize the governor's inaction as anything but political posturing to weaken the mayor.

We have the solutions, now we need our top elected officials to put aside the politicking and blame-shifting and take the steps to finally end this awful homelessness crisis.

***

Alyssa Aguilera is the Political Director of VOCAL-NY, a grassroots community organizing group, which is a member organization of the Homes for Every New Yorker campaign.

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

PBA Continues Misguided Resistance to Reform

(photo: @NYPDnews)

Last week the NYPD and a Federal Court appointed "stop and frisk" monitor came to agreement on the distribution of informational receipts to be given out to people stopped by the police. The cards will contain identifying information about the officer and the reason for the interaction. This is one of several potential outcomes of the "stop and frisk" community remediation process now underway stemming from the Floyd v. City of New York decision.

The idea for the cards came out of efforts by Communities United for Police Reform to dial back abusive and discriminatory police stops which numbered in the hundreds of thousands just a few years ago and overwhelmingly targeted young men of color. A very similar proposal is contained in the organization’s package of police reforms now before the City Council, commonly referred to as the Right to Know Act.

The thinking behind the proposal is that police will be less likely to engage in unlawful, abusive, or disrespectful stops if there is enhanced accountability. In addition, the cards can be used to help people document the stop and possibly aid in their efforts to bring Civilian Complaint Review Board cases. While in practice police might not give out the cards as required in every interaction, failure to do so would be a violation of administrative policy.

This new procedure is no cure-all for the problems of discourteous, abusive, and excessive policing, but it is a step towards greater transparency and accountability and could play a role in reducing some abusive practices by officers.

It is also in keeping with the department’s professed goal of increasing respectful communication between officers and the public in the hopes of achieving greater mutual understanding. However, the problem of completely respectful and lawful overpolicing will remain.

A courteous ticket for riding a bike on the sidewalk or a respectful arrest for selling loose cigarettes is still a deeply problematic example of ballooning police power and the criminalization of everyday life for too many people.

In response to these rather benign efforts at basic transparency and legal accountability, Police Benevolent Association President Pat Lynch issued a deeply disturbing statement condemning the move:

“With the CCRB’s contact information prominently listed on the back, these receipts are clearly designed to invite retaliatory complaints against police officers who make an active effort to prevent crime and take guns off the street. They are just one more item on the ever-growing list of anti-public-safety measures that will put an end to proactive policing in this city and ultimately accelerate the increase in crime and disorder that we are already seeing in our public spaces.”

While unions have the right to speak out about public policy measures that affect their members, they should be held publicly accountable for those statements. Pat Lynch's comments will only serve to inflame community tensions and undermine public confidence in the NYPD, which is already experiencing a significant legitimacy crisis in many communities of color.

By attempting to evade transparency and accountability, he is signaling to his members and the public that police have something to hide about the way they interact with the public. Further, his suggestion that accountability hurts crime fighting is based on the faulty belief that the only way to reduce crime is through aggressive, disrespectful, and unconstitutional policing. This is a deeply disturbing view of policing and should be of great concern to elected leaders and the public.

It also seems a bit disingenuous to express such a high level of concern about the potential for retaliatory complaints against officers. Any review of the outcome of such complaints should greatly reassure him since so few of them actually result in any negative consequences for officers. Even with recently enhanced powers, the CCRB rarely substantiates claims against officers and even when it does, meaningful consequences are infrequent. The mere possession of one of these information cards, in the absence of extensive corroborating evidence, will hardly prove sufficient to substantiate a complaint under current evidentiary standards.

It’s time for Pat Lynch and the officers he represents to stop being part of the problem of poor police-community relations. He could start by acknowledging that a problem exists and begin working with reformers and community activists to repair some of the damage caused by years of racialized overpolicing.

The rank-and-file members of the NYPD did not create the current situation all on their own; our elected leaders have encouraged an expanded and more aggressive role for the police, placing them on an untenable “war” footing all too often. At the same time, elected officials should politically isolate any union leader that shows such contempt for the public they serve and look for concrete ways to diminish police power by finding more effective and less punitive alternatives.

***

Alex S. Vitale is associate professor of sociology at Brooklyn College and author of City of Disorder: How the Quality of Life Campaign Transformed New York Politics. He is senior policy adviser to the Police Reform Organizing Project and serves on the New York State Advisory Committee to the US Civil Rights Commission. You can follow him on Twitter: @avitale

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

JFK International: The Airport New York Deserves

JFK (photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

Many are the sins of the Port Authority. Administrators made bad decisions about the original design for JFK, saddling the airport in the 1950s with large and widely separated terminals that have complicated renovation ever since. They also resisted creating mass transit links to JFK, finally opening the AirTrain over half a century after the first flights took off over Jamaica Bay.

Nor did the Port Authority over the decades show much talent for day-to-day management of facilities at the airport, leading to dirty bathrooms, shabby terminals, and delays.

Yet in the last two decades the Port Authority, and the airlines that operate at JFK, have spent billions of dollars collectively to redevelop the airport's terminals.

We now have a popular and functioning rail link, at least to the subway and LIRR. The AirTrain, a passable mass transit option, carries over six million travelers and workers per year. Most airport roadways have been rebuilt, signage is better, and security much enhanced. New air traffic technology is slowly reducing delays.

JFK is still regularly voted one of the country's "worst airports," but the truth is that the place works about as well as anything else in New York--and therein lies the problem.

JFK has rebounded in international travel, in large measure because the New York region has had a tremendous growth in tourism. In 2000, 6.8 million international visitors came to the city; last year it was an amazing 12.2 million.

JFK is handling two thirds of the international travelers flying into the metropolitan area's three major airports. But the airport cannot boost the region's economy at full throttle if New York's leaders, and the people who elect them, do not change the rules of the game.

Companies need better access to workers, customers, and suppliers on a more reliable aviation transportation system. Otherwise, they will pack up and go somewhere else. Consumers also rely upon air cargo more than they realize. Whether it's Tiffany's, Walmart, or Apple; an affordable sushi dinner, inexpensive roses on Valentine's Day, or antibiotics when you get sick—high volume, low cost air cargo makes it all possible.

Every year, New York's airports ship in and out over $200 billion dollars worth of products including machinery, apparel, food, and medical instruments.

Yet the region's leaders have not done anything, beyond the AirTrain, to upgrade passenger connections to create the all-important "one seat ride" from Manhattan business centers to the airport. Nor have the many plans to upgrade freight access to Long Island and JFK reached fruition despite JFK's tremendous loss of market share in air cargo over the past three decades.

This lack of action, which discourages much trade and business at JFK, is the result of inaction by many political leaders and agencies rather than malfeasance of the Port Authority.

JFK also remains hemmed in by unnecessarily congested highways, a situation that has eroded the airport's supremacy in air cargo and hurt its passenger business.

Although larger tractor-trailers were finally allowed last year on New York City highways, no city in the world has as many truck free "parkways" girdling an airport. As a result, the heavily congested Van Wyck Expressway and slow service roads remain the only routes out of JFK for trucks. Long Island and city residents, concerned about a stagnant economy, may have to reconsider the logic of narrow landscaped parkways.

The four runways at JFK are also far below what is needed to handle the passenger business at one of the world's leading international airports. O'Hare, for instance, has eight and has spent billions reconfiguring its runways to reduce delays and boost capacity.

The Regional Plan Association, the Port Authority years ago, and many others have made some logical proposals for expansion of runways into Jamaica Bay or on the landside. Their pragmatic proposals would boost operations and reduce delays in bad weather with minimal noise and environmental impacts. Those plans have gone nowhere.

In light of the fact that Jamaica Bay has yet to realize its promise as a great ecological park, and was compromised further by superstorm Sandy, city and federal officials need to seriously consider using more of its surface for aviation.

The Bay and its environs are, after all, places where commerce, residence, and nature have always mixed. New oysters beds in the water under additional runways, and fewer marshes and gulls near the runways, would yield a cleaner and more resilient bay—and fewer bird strikes.

The Port Authority could also be forced to mitigate any habitat losses at JFK with marsh restoration on other sites, far away from airplanes.

There are many cities both here and abroad that stand ready to absorb New York City's growth; aviation technology is making it easier to bypass crowded New York.

JFK is a remade airport today, but its growth pales in comparison to its peer global cities. Transportation is the key determinant of where companies will locate.

If New York is going to have a diversified economy, including decent jobs for the working class, making space for air cargo and aviation—which employ large numbers of entry level workers—makes a lot of sense, especially because it can be done in an environmentally sustainable way.

***

by Nicholas D. Bloom and Philip M. Plotch

Bloom is associate professor at the New York Institute of Technology where he is also Chair of Urban Administration and Interdisciplinary Studies. He has written many books including The Metropolitan Airport: JFK International and Modern New York and the forthcoming edited collection from Princeton University Press, Affordable Housing in New York: The People, Places, and Policies That Transformed a City.

Plotch is an assistant professor of political science and director of the Masters in Public Administration program at Saint Peter's University in Jersey City. He is the former director of World Trade Center Redevelopment and Special Projects for the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, and the former manager of planning for New York's Metropolitan Transportation Authority. He is the author of Politics Across the Hudson: The Tappan Zee Megaproject.

Real Solutions to the Scandal of Struggling Schools

Chancellor Fariña (photo: @NYCSchools)

There’s been lots of news and commentary lately about fraudulent credit recovery schemes and grade fixing practices at city schools. The editors of the New York Post predictably want to pin the blame on Mayor de Blasio – with op-eds written by critics such as Senate Majority Leader Flanagan, who claim that these scandals are a good reason to question the extension of mayoral control of city schools.

Truth is that these schemes spread like a virus first under Mayor Bloomberg – the result of pressure on schools to improve quickly or be closed, combined with a troubling lack of oversight to see that improvements were based on real learning and not gimmicks. Credit recovery was widespread, along with instructions from principals that teachers should pass 60 percent of their students “or else.”

Despite the fact that this troubling phenomenon occurred during the Bloomberg administration, Senator Flanagan was then one of the biggest boosters of mayoral control, and in 2009, helped renew it for another six years. This was probably not unrelated to the fact that Bloomberg was also the biggest financial contributor to the Republican Senate majority.

Now that de Blasio is mayor, the hedge-funders and the charter lobby have replaced Bloomberg as the biggest contributors to the state GOP, and keeping its members in charge of the Senate. And as de Blasio has consistently opposed the efforts of these same groups to expand charters and privatize our public schools, Flanagan and the editors of the Post are predictably eager to use the scandal to threaten him with the loss of mayoral control.

To her credit, reporter Sue Edelman, who has broken many of these stories, made it clear in the Post that these fraudulent practices are not new:

Credit- and grade-boosting schemes went into full swing under Mayor Mike Bloomberg, who boasted of raising the citywide graduation rate to 64.2 percent in 2014. Last year, the rate rose to 68.4 percent. But both years only 38 percent of the grads had test scores high enough to enroll in CUNY without remedial help.

But even if this credit recovery and other artificial methods of juking the stats took hold during the Bloomberg years, the de Blasio administration cannot be let off the hook for allowing them to continue.

Edelman’s piece recounts the scandalous allegations at Dewey, Flushing, Richmond Hill, Bryant and Automotive High Schools, which until recently were met with little more than a shrug from both Chancellor Farina and the mayor. Teachers at Dewey in particular had been reaching out desperately for more than a year, before their copious evidence of fraud was finally taken seriously, and principal Kathleen Elvin dismissed in July.

I began to get anguished messages from teachers at Dewey in September 2012. Starting in February 2014, teachers reported the credit recovery to Special Investigator Condon and others. Soon followed numerous exposés in the Post, and by Marcia Kramer of CBS News and Juan Gonzalez of the Daily News, who catalogued in great detail the outrageous techniques of the principal to boost the graduation rate.

Yet in March, de Blasio said, referring to the Dewey scandal and the much-derided capability of the internal DOE investigative unit, “I don’t assume because some teachers talked to you that that’s the whole truth. I believe very, very strongly in the quality of our investigations unit. I have absolute faith in the integrity of that unit.”

As recently as this past June, Farina minimized the clear evidence of the principal’s misdeeds.

In this way, she and the mayor have played into the hands of their opponents. Even now, by appointing a group made up almost exclusively of DOE officials to look into the scandals instead of an independent panel of investigators, the administration seems tone deaf about how its efforts to stem the tide of corruption will be portrayed.

The administration has been less than transparent on a whole host of education issues – as the NYC Kids PAC report card pointed out.

There are 94 schools on the city’s “Renewal” list. These schools, many of which have been struggling for years, are under tremendous pressure to increase test scores and raise graduation rates or be closed or taken over by the state. Yet so far, the remedies introduced by the administration focus on “wrap-around” services – which do not directly address these students’ academic needs – as well as replacing teachers, appointing new administrators, and encouraging more professional development.

These schools do not need a whole new raft of inexperienced teachers. In March, de Blasio visited Automotive High School and said, “It is impossible to sit in one of those rooms and not immediately identify the level of commitment so many of our teachers have – how much they believe in the work they’re doing...These teachers are committed, energetic, creative, and they’re committed to the future of this school.” And yet last month, it was reported that 63 percent of the teachers at those schools had left or been forcibly removed.

Nor do these school need yet more high-priced administrators, though the Renewal division at Tweed is expanding fast and will have 45 administrative positions, many of them at top salaries, filled by the end of the summer. It is also unlikely that more teacher training and professional development will turn around these schools. An article in Politico NY relates how Farina recently met with Karen Ames, the new Superintendent of District 8 in the South Bronx, who briefed her on efforts to improve the Renewal schools in her district:

Ames, [is] the new superintendent of District 8, which encompasses a swath of largely low-income neighborhoods in the Bronx…[Ames is] a former network leader in prestigious District 2, the same Upper East Side region where Fariña spent years as principal of P.S. 6, came prepared for her meeting with the chancellor, whom she has known for years….Ames recently led several principals of Renewal Schools in her district on a tour of District 2’s Salk School of Science, one of the city’s best middle schools. Fariña praised the idea of the Salk tour…

It is astonishing that principals of District 8 renewal schools are being asked to visit Salk Middle School on the East Side of Manhattan for tips on how to improve their schools, given their vastly different student populations. Salk is a selective middle school that takes only the highest scoring students, and serves a primarily middle class and even comparatively wealthy school population. Only 11 percent of Salk students qualify for free lunch, according to Inside Schools; and it is home to no English language learners. Its students are 64 percent white; 21 percent Asian, 4 percent black, and 9 percent Hispanic.

Contrast those statistics with the four Renewal middle schools in District 8:

- The Bronx Mathematics Preparatory School – 95 percent free lunch; 26 percent special education; 10 percent ELL; 95 percent black and Hispanic.

- Hunts Point School – 91 percent free lunch; 28 percent special education; 25 percent ELL; 99 percent black and Hispanic.

- Urban Assembly Academy of Civic Engagement: 79 percent free lunch; 30 percent special education; 13 percent ELL; 96 percent black and Hispanic.

- M.S. 301 Paul L. Dunbar: 83 percent free lunch; 27 percent special education; 24 percent ELL, 97 percent black and Hispanic.

According to the Independent Budget Office, all the Renewal schools have much larger numbers of English language learners, immigrant students, students with disabilities, and students in temporary housing, as well as more black and Hispanic students than the system as a whole.

What the students in these schools desperately need is intensive tutoring and small classes to make significant improvements, not a new cadre of inexperienced teachers or administrators breathing down their necks. And yet more than 60 percent of the Renewal schools still have many classes with 30 students or more, according to DOE data.

When Rudy Crew was chancellor, he drew the lowest-performing schools in the city into a new program called the Chancellor’s District, and capped class size in all of their classes at no more than twenty students. This worked effectively to raise achievement. Yet not a single elementary or K--8 school on the Renewal list had capped class sizes at 20 students in grades K-3 last year, as most experts would recommend. These were also the goals that the state demanded the DOE achieve citywide in its class size reduction plan in these grades, as part of the settlement of the Campaign for Fiscal Equity lawsuit in 2007.

Only eight middle or 6-12 schools out of 43 Renewal schools last year had capped class sizes at 23 students in grades 6-8, and only one renewal high school out of 31 had capped class sizes at 25 – the goals for those grades in the city’s original class size reduction plan. More than half of the high schools had at least some classes with 35 to 44 students - which mean they violated union contract levels.

The real scandal is that hundreds of thousands of New York City high school students, including those at schools that have allegedly engaged in credit manipulation, like Richmond Hill, Flushing, and Automotive, continue to struggle in large classes of 34 or more.

Rudy Crew had a vision of what high-poverty students need to succeed; but right now, there is no comparable vision on the part of this administration. If we are talking about accountability for schools and teachers, we must also address the accountability of those in charge of running our schools, and here the mayor and the chancellor have unaccountably failed.

***

Leonie Haimsonis the Executive Director of Class Size Matters. Follow her on twitter @leoniehaimson