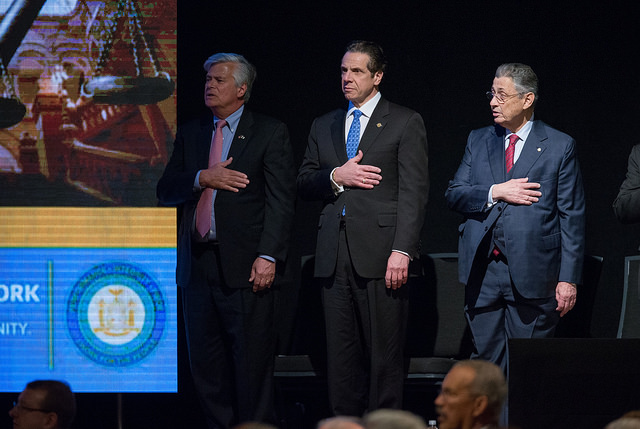

Skelos, Cuomo, Silver (l-r) (photo via The Governor's Office, Jan. 2015)

Former Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and former Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos were each told by their judge during recent prison sentencing that their corrupt actions have increased public cynicism around state government. Their corrupt actions, they were told, make people question what might have been different in the budgets and policy deals they negotiated, government decision-making that impacted millions. Judge Kimba Wood told Skelos we “can’t know” how his budget advocacy would have differed had he not been corrupt.

In fact, everything that has come through the state Legislature during Silver’s or Skelos’ tenure is open to questioning based on the facts that we now know they were illegally using their public positions for private gain and that nothing goes through either chamber without its majority leader signing off. In the wake of their convictions, every decision either was involved in could be worth reviewing, not that such an investigation is necessarily warranted or welcome.

For years, SIlver and Skelos were two of the “three men in a room” negotiating budget and other deals, approving what legislation came to a vote in their houses and directing policy initiatives. The third man in that equation, Governor Andrew Cuomo, currently faces a vast probe into his administration’s signature economic development program.

As Albany grapples with a wave of corruption convictions highlighted by those of Silver and Skelos, it does so with ethics laws negotiated by two men who have now been sentenced in major federal corruption cases and under the watch of an ethics body they not only helped create but appointed members to. The latest convictions also follow the shutdown of The Moreland Commission on Public Corruption, which was ended prematurely in a deal among Cuomo, Skelos, and Silver.

A Siena poll released on the day of Silver’s early May sentencing found 93 percent of New Yorkers think corruption is a major problem for the state and 97 percent want new laws to combat corruption.

With 16 lawmakers forced from office due to misconduct in the last six years, the nearly simultaneous downfall of the two legislative leaders, and U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara’s continued insistence that everyone “stay tuned,” the questions arise: How tainted were the budget- and law-making processes? Should decisions engineered and shepherded by corrupt officials stand?

Those are questions, according to former Assemblymember Richard Brodsky, currently a Demos scholar, that are in the hands of Governor Cuomo and the Legislature.

“If the governor or Legislature has concerns about the integrity of a law, it can be repealed, re-enacted, etcetera,” said Brodsky. He added, though, “Remember, the motive of a bill's author is what it is. It takes 76 Assembly votes to pass a bill no matter who the sponsor is.”

It is nearly impossible to imagine the governor or lawmakers wanted to revisit decisions made during the tenure of Silver or Skelos to investigate whether certain decisions were made in relation to their scandals.

Gerald Benjamin, professor of political science at SUNY New Paltz, concurred that no matter how powerful Skelos or Silver was, laws passed by the Legislature are the action of “an institution,” not “one legislator.”

Benjamin said he knows of no case where a law was later “examined due to a general charge of corruption.”

Jennifer Rodgers, a former U.S assistant attorney and current head of Columbia Law School’s Center for the Advancement of Public Integrity, said that the Silver and Skelos convictions don’t prove that either of them manipulated legislation. “And the opacity of the proceedings leaves us in the dark as to what they actually did,” she said, referring to Albany’s “three men in a room” decision-making culture. Because of that, Rodgers said repealing a law due to corruption does not seem to be “a realistic avenue to pursue -- you couldn't prove that the bribe caused the legislation to pass or fail.”

Silver, the long-time Democratic Assembly Speaker known for getting his way in budget deals by holding out longer than anyone else, was convicted of sending government money to a doctor who researched cures for mesothelioma in return for the researcher referring patients to a law firm that in turn paid fees to Silver. Able to tap into opaque pots of discretionary money called State and Municipal Facilities Program funding, Silver quietly funded the doctor’s work.

Silver had a similar deal with two real estate firms that moved their business to a law firm that paid Silver in exchange for supporting rent legislation that they backed.

At the time of his misdeeds, Silver was considered by some to be tenants’ best hope in negotiations over rent laws as Senate Republicans favored real estate. Tenant advocates now see many of the actions taken by Silver, including renewing controversial tax breaks for developers and his back-room dealings on the extension of rent regulations, as tainted.

Skelos, meanwhile was accused of extorting three firms with business before the state to employ his son Adam, who rarely showed up to work and often made problems when he did. Those businesses were real estate firm Glenwood Management; an environmental technologies firm, AbTech Industry, which wanted to earn lucrative state contracts having to do with Hurricane Sandy and hydraulic fracturing; and Physicians Reciprocal Insurers, which gave Adam Skelos a $78,000-a-year job. PRI was hoping for favorable action from Dean Skelos on legislation having to do with medical malpractice.

Skelos also benefited from State and Municipal Facilities Program, or SAM, funds. He was able to secure hundreds of millions of dollars in discretionary funding for projects at universities and colleges all over Long Island.

In Albany it is rare for major legislation to move independently. Legislative leaders and the Governor generally have two major sets of negotiations a year: early in the year around the budget, especially in the days leading up to the April 1 deadline, and during the post-budget legislative session, especially the days nearing its June end.

Budget negotiations are notorious for being sorted out in intense, closed-door meetings by the three leaders while rank-and-file legislators remain mostly in the dark. Items included in negotiations rarely adhere to generally accepted budget issues and allow the governor to trade spending increases or threaten cuts for other policies.

In post-budget session, lawmakers usually jam through a “big ugly” deal at the end, again with much secrecy and little time for many legislators or the public to review.

With so much opportunity for behind-the-scenes horse-trading it is impossible to know what exactly was influenced by Silver or Skelos, but it is also impossible to rule out that the corrupt practices they were convicted of didn’t color the major deals they oversaw.

Laws have been challenged in court due to what plaintiffs charge were improper procedures. The gun control package Cuomo pushed in the wake of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting faced a lawsuit over the use of a message of necessity. State law requires bills to age three days before coming to a vote. Cuomo issued a message of necessity, saying that introducing the bills and allowing them to age would lead to a rush on gun stores. Courts withheld Cuomo’s use of the message and have generally deferred to the governors on such matters. The governor has repeatedly used messages of necessity to move budget deals through, giving legislators minimal time to review thousands of pages of bill language before having to vote.

“Concerns of disruption and consequences of undoing laws weigh heavily on all of this,” said Professor Benjamin, indicating how unwieldy a review process could be.

Rodgers said that “unwinding legislation is not one of the remedies available in a criminal case.”

Even if it were, she said she sees “A huge problem to this notion of trying to undo legislation (even if it is procedurally possible, which I don't know enough to offer an opinion on), which is proving causation."

Rodgers said “given the lack of transparency of how things are actually passed in Albany,” even if there was a lawsuit brought seeking an injunction on behalf of an impacted company that wanted to undo legislation, “It seems to me that even in a civil court it would be impossible to prove that a bribe, even if the bribe itself was proved beyond a reasonable doubt in criminal court, was the proximate cause of the plaintiff's harm, assuming a plaintiff could even prove harm.”

***

by David King, Albany editor, Gotham Gazette

@DavidHowardKing @GothamGazette