(photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Governor’s Office)

More than 49,000 people on parole in New York had their voting rights restored under a conditional pardon order, signed by Governor Andrew Cuomo, in the year-and-a-half since it’s been in effect.

The Department of Corrections and Community Supervision told Gotham Gazette Thursday that 49,485 people have been re-enfranchised since the program launched in May 2018. Of those, 7,943 were later revoked, either because of a parole violation or a new conviction. Officials won't say how many parolees were not given voting rights after their case was reviewed pursuant to the order.

The initiative, created through executive order, is a leap away from the Jim Crow-style disenfranchisement of people involved in the criminal legal system in New York State, where roughly half of the 46,000 people incarcerated in state prisons and 35,855 on parole are African-American. Civil rights advocates want to see the state deepen its commitment by codifying the order into law to protect it under future administrations. And some advocates believe it’s time to go further still, extending the franchise to people in state prison.

“It’s a giant step for the state of New York. But we have still not reached the finish line,” said Esmeralda Simmons, the founding executive director of the Center for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn. “The people that we are urging to be restored to their voting rights are citizens of this state and of this country. And as citizens, the right to vote is a sacred trust and responsibility.”

For years, criminal justice and voting rights advocates have been pushing for rights restoration upon release from prison. State lawmakers have been sponsoring legislation to that effect since 2010, but bills have only twice moved out of committee in either house and they have never come to a floor vote, according to the State Senate website.

With Cuomo’s executive order, which was criticized by Republicans as an election year gimmick and praised by Democrats, New York joined 18 other states and the District of Columbia in authorizing people on parole to vote. But there’s no guarantee it won’t be pulled back by a successor to the governor’s mansion. The next state legislative session begins in January, offering lawmakers a new opportunity to codify the action in the second year of full Democratic control of both houses of the Legislature and the executive chamber.

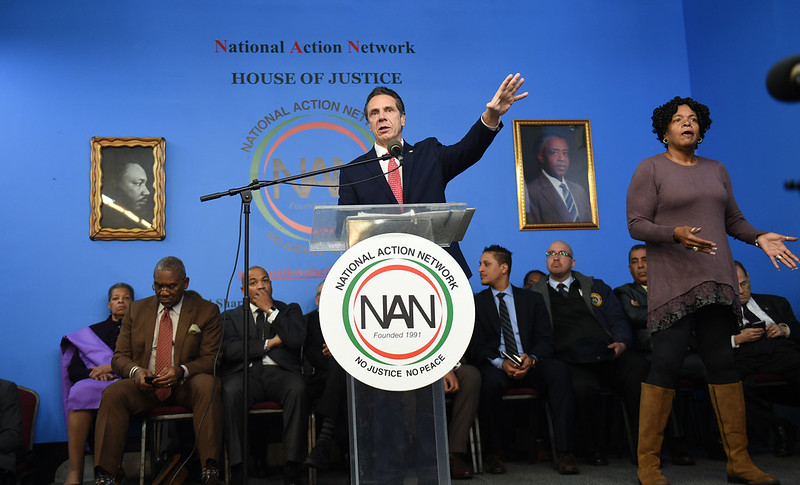

Cuomo announced the executive order on April 18, 2018, at a conference in New York City hosted by Reverend Al Sharpton’s National Action Network, while campaigning for the Democratic nomination for a third term against challenger Cynthia Nixon, who was running to Cuomo’s left. Standing next to former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, the governor said, “I proposed a piece of legislation, General Holder, this past year that said parolees should have the right to vote. The Republican Senate voted down that piece of legislation, which is another reason why we need a new Legislature this November.”

“But I’m unwilling to take ‘no’ for an answer,” he continued. “I’m going to make it law by executive order and I announce that here today.”

Under the current order, on a monthly basis the governor’s office will review a list provided by DOCCS of every person released from incarceration onto parole during the prior month and make a determination as to whether they will be given voting rights. A month after signing the order, Cuomo announced the re-enfranchisement of 24,086 people under what the department calls “community supervision,” or parole.

The order says that individuals on parole are active participants in society and should be “permitted to express their opinions about the choices facing their communities through their votes.” It further states, “the disenfranchisement of individuals on parole has a significant disproportionate racial impact thereby reducing the representation of minority populations.”

Criminal convictions have been used to suppress black voters, in New York and throughout the country, since the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments granted equal citizenship to freed African-Americans and outlawed racial discrimination in voting. It works in tandem with laws that have disproportionately ensnared non-white people in the criminal legal system.

According to a press release issued by the governor’s office at the time the executive order was signed in 2018, “African Americans and Hispanic New Yorkers” comprise 71 percent of people disenfranchised because of their status on parole. There are currently 46,000 people in state prisons, according to the DOCCS website, of which the latest statistics show 48 percent are African-American, and another 24 percent Hispanic.

Until 2013, the history of racial disenfranchisement in many parts of New York State, including New York City, required preclearance from the U.S. Attorney General under the 1965 Voting Rights Act before any changes impacting voting could be made. In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled part of the Voting Rights Act outdated and unconstitutional, rendering the preclearance provision unenforceable, a cut to civil rights activists who lamented the loss of the historic and hardwon provision.

While applauding Cuomo’s executive order, many advocates had hoped to see it included in the slew of long-sought voting reforms passed the following session by the Democratic-controlled State Legislature.

“Restoring the right to vote to people who have paid their debt to society only strengthens our democracy, while promoting successful re-entry into our community and ultimately, making New York a safer and more just place to live,” wrote Caitlin Girouard, the governor’s press secretary, in an email. “Under Governor Cuomo’s leadership, New York is making it easier to vote – from early voting to modernizing our election system - because voting is a basic right of citizenship and fundamental to our society.”

Advocates want to see legislation passed and enacted as soon as possible, concerned with what they have seen as a tepid approach to re-enfranchisement in Albany -- especially in the wake of the so-called “blue wave” 2018 elections that swept a cohort of progressive lawmakers into office this year. “It was on the table last year when all of the historic voting rights legislation passed, things that voting rights advocates have been asking for for 20, 30, 40 years...The fact that this was dropped was a bad signal,” Simmons said.

She added, “But that doesn’t mean it will not happen. I believe its time has come.”

A bill sponsored by Senator Leroy Comrie and Assembly Member Daniel O’Donnell, both New York City Democrats, would have codified re-enfranchisement upon parole. It would also require state agencies to develop support and outreach programs for people leaving prison, and training for the public servants involved in the process. But the legislation failed to gain traction and died in committee.

Let NY Vote, a coalition of good government, grassroots, and labor organizations, which was instrumental in pushing state voting reform in 2019, will be pushing to codify voting rights for people on parole in the next state legislative session, which is about to begin.

According to Sarah Goff, Deputy Director of Common Cause NY, a founding member of the coalition, the group will also be pushing for the full voting rights of people who are currently incarcerated.

That would set New York apart from most other states, placing it with one of the least restrictive voting laws for people who have been incarcerated. Only two states -- Maine and Vermont -- allow people in prison to vote. Goff said accompanying that push will be an effort to amend the state constitution to prohibit prison-based gerrymandering.

“The advocates from the formerly-incarcerated community who have been so heroic in pushing reforms forward in New York City and New York State...were very disturbed at the turn of events and are pushing forward with our full support to make sure that this happens this time around,” Simmons said, speaking for The Center for Law and Social Justice, which is also a member of Let NY Vote.

How Parolee Re-enfranchisement Works in New York

Since Cuomo signed the April 2018 order, the governor’s office has worked with the Executive Clemency Bureau within DOCCS to review each case based on a number of factors, “including if the person is living successfully in the community by maintaining required contact with his or her parole officer and remaining at liberty at the time of the review,” a DOCCS spokesperson wrote in an email. Voting rights are revoked again if a person goes back to jail, either for a parole violation or a separate felony conviction.

The DOCCS spokesperson wrote: “Every individual who was under parole supervision, as of April 18, 2018, and every individual who has since been released from state correctional facilities to parole supervision has been reviewed by the Department’s Executive Clemency Bureau to determine their eligibility for a conditional voting pardon.”

Asked how many of them had not received the conditional pardon the spokesperson replied, “No comment.” The governor’s office did not respond to the question in an email.

According to DOCCS, the pardons are hand-delivered by a person’s parole officer, along with a voter registration form and location of the office where it can be submitted. Individuals can also find the status of their rights restoration using the Parolee Lookup feature on the DOCCS website. The spokesperson confirmed the list and other information are reviewed each month by the governor’s office before a conditional pardon is granted or revoked.

Of the 38,855 people under community supervision in New York State, a DOCCS factsheet published December 1 indicates 15,670 individuals are in New York City. The boroughs with the most parolees are the Bronx and Brooklyn, with 4,500 and 4,400, respectively. Manhattan is home to about 3,400, Queens 2,800, and Staten Island just 585.

“We need to have those voices heard at the ballot box. A democracy is not a democracy unless all citizens are able to participate.” Simmons said.

***

by Ethan Geringer-Sameth, reporter, Gotham Gazette

@GeringerSameth @GothamGazette