Mayoral Issue Grid: Environment

ENVIRONMENT

-Mayor's Waste Plan?

-Bronx Water Filtration

Garbage is a critical issue for New York City. Since the closing of the Fresh Kills landfill in 2001, the city has paid high prices to ship its waste out of state. And 80 percent of the waste is currently handled by waste transfer stations in four, low-income neighborhoods

In October 2004, the Bloomberg administration issued a new solid waste plan, which would move most of the 50,000 tons of trash the city produces each day by rail or barge, instead of by truck. To do this, the city proposes reopening four marine transfer stations, piers where trucks can dump trash onto barges, to handle the city's residential waste. Critics say the plan does not address many issues like commercial waste or recycling. And it does not solve the problem of where the garbage ends up and how much the city must pay other states to dispose of it.

Safe, clean drinking water is also a critical issue for New York City and a state court ruled that the city must filter water that comes from the Croton Reservior. A water filtration plant in Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx was first proposed by Mayor Rudolph Giuliani in the late 1990's and generated heated political debate. Some environmentalists argued that the water does not need to be filtered; parks advocates said it should not be built in limited green space; and residents of the north Bronx fear years of construction, noise, and dust. The plan was abandoned in 2001 because it lacked support of elected officials.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg revived the plan by offering two concessions. The city committed $240 million for building and improving parkland in the Bronx and the city's Department of Environmental Protection agreed to do an environmental impact study.

At a 1999 hearing on the filtration plant, Ferrer, then the Bronx borough president said, "I'm here to personally convey that the Bronx is unanimous in its unequivocal opposition to the Croton water filtration plant." This, though, was before the Bronx was promised the money for parks - and Ferrer has not been on record as being so unequivocal this year.

C. Virginia Fields supports the solid waste management plan, but she wants to improve the waste reduction, reuse, and recycling aspects of the plan.

Fields says she opposes the water filtration plant in Van Cortlandt Park, but at a recent forum, she said she would not stop it. "In all fairness and candor, unless you have a different way of approaching it, I don't think as mayor I could stop it as it has been started and I recognize everything that went into ultimately making that decision," she said.

Gifford Miller says he supports many of the principles in the solid waste management plan, but as head of the City Council is working to improve the plan to focus on increased recycling, waste reduction and long-term solutions to solid waste problems. He also opposed the creation of a marine transfer station on East 91st Street in his district.

Miller voted in favor of the filtration plant in the City Council, calling it the best option for bringing clean water to the whole city.

Anthony Weiner supports the principles of the solid waste management plan, but says that he will make reducing waste the top priority.

In a questionnaire for the New York League of Conservation Voters, he wrote: “As mayor, I would develop incentives for New Yorkers to reduce the garbage they generate – providing a property tax deduction for businesses and households that demonstrate significant reductions. Conscientious New Yorkers should get a signal of support from the city, rather than having to pay for the waste of their neighbors.”

Weiner opposes the filtration plant in the Bronx and has criticized Mayor Bloomberg and Gifford Miller for approving it.

Michael Bloomberg proposed the solid waste management plan that uses marine transfer stations rather than trucks.

Bloomberg was responsible for reviving the filtration plant project in Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx. He won the support of many local officials by offering $240 million for building and improving parkland in the Bronx.

Real Estate Developers Should Help Pay for Parkland

Density, in many ways, is what makes New York City great. But New York is getting ever denser; between 1990 and 2000, it grew by 685,000 people -- the entire population of Austin, or twice the population of St. Louis.

Crowded indoor living needs to be balanced with open space. For every new apartment tower built, brownstone rehabbed or single-family home subdivided, we need a small parcel of compensating parkland for our outdoor well-being -- for recreation, health, social connections, views, appreciation of nature and trees, environmental improvement. Elsewhere, residents have yards; New Yorkers have parks. With more New Yorkers, there is a need for more parks.

In an ideal world, government would bear the full responsibility of providing and maintaining parks. But in today's real world of unfunded federal mandates and local-level anti-tax pressure, a patchwork quilt of public-private partnerships has grown up. If developers are making money building housing for new residents, it seems reasonable to ask them to provide some new parkland, too.

Many communities around the country require developers to donate land or pay in-lieu fees to help governments acquire parkland. Known as "developer exactions" or "developer impact fees," the concept is generally thought of as suburban – setting aside parcels for playing fields or stream-valley trails among the new tract houses. But it's also the law in Atlanta, Portland, Oregon and Los Angeles and in very densely populated Chicago, Miami and Long Beach, California.

Miami charges developers $157 for every 1,000 square feet of downtown residential construction and $104 for every 1,000 square feet of downtown commercial construction. The money must be spent in the general vicinity of the new building, it must be spent within six years, and it can only be spent for capital purposes (buying land or constructing a park facility), not ongoing maintenance.

Chicago's Open Space Impact Fee is similar, though somewhat steeper -- about $313 for a small apartment and up to $1,253 for a large one. Affordable (below-market) housing units are assessed a flat fee of $100. The city has seven years to spend the money or it must return it to the developer. In case of larger planned developments, the city prefers to receive not money but a comparable gift of land.

Long Beach, California, which charges up to $2,680 per dwelling unit, hopes to produce precisely 38.72 square feet of new parkland for every new resident – about the size of a double-bed.

Maybe it's time for New York to create a developer exaction program, too. New York has an informal system of bargaining with developers for street-level plazas in return for allowing more building height, but this is not an exaction program - and it doesn't do much for the outer boroughs where the population growth is taking place.

If New York had had an exaction law from 1990 to 2000, housing the 685,000 new residents could have yielded something like $360 million for park acquisition - perhaps more than 300 acres of relatively desirable land around the city. This is not a panacea, but it's not insignificant, either. That's one park the size of Riverside Park, or 35 of them the size of Bryant Park.

Do these programs really result in more parkland? To determine this, the Trust for Public Land's Center for City Park Excellence, where I am the director, undertook a study of the experience of 12 cities. Results were mixed. In six of the communities for which records were kept, a total of 1,329 acres of new parkland was acquired through developer fees. However, this was only about 60 percent of what we calculated should have been acquired. Still, 60 percent is better than zero percent, where New York is right now.

Developer exactions can be controversial. Most developers feel that they are already doing enough, after all, by providing housing. They also argue that paying for parkland will raise the cost of apartments even higher than they already are. That may be true, but doing so might also help keep taxes a bit lower. (Also, with parkland,the apartments will be worth more.) And, ultimately, city living has to be more than a clenched-teeth trip through urban canyons between an apartment and a job. New York has already experienced parkless tenement life, back in the 19th century, and no one wants to return to that.

By every measurement, New York City has one of the most fabulous park systems in the nation. Much of it was created by our forebears beginning in 1859. While we continue to upgrade and steward this priceless legacy, it is important that we also leave more parkland to our children. Instituting a developer exaction program would be one way to do so.

Peter Harnik is the director of the Center for City Park Excellence at the Trust for Public Land.

Â

Recreation for Youth In Short Supply

On a Friday afternoon in Prospect Park, a Little League team looking to practice finds that all the diamonds are full. In the South Bronx, a principal says her students go home after school and stay indoors because there’s no safe place to play outside. Parents wait on line for hours to sign up their children for private swim classes, if they can afford them, unless they live in one of the few neighborhoods with a public pool.

Ask parents about sports and recreation in New York City, and they are likely to say, "There’s not enough." Whether in minority neighborhoods that have disproportionately fewer parks and sports fields or in affluent areas with a growing demand for the kind of sports programs found in the suburbs, there are not enough facilities and programs to meet the needs of the city’s 1.5 million school age children.

Addressing these needs has become increasingly important as a growing body of research demonstrates that exercise and organized recreation can promote the healthy physical, social, and emotional development of children.

A 1996 report by the U.S. Surgeon General found multiple health benefits from engaging in regular physical activity, including weight loss and a reduced risk of diabetes, cancer, and heart disease. A study by the Department of Education found that 43 percent of New York City students from kindergarten through fifth grade are either overweight or obese. Obesity rates were highest in central Brooklyn, East and Central Harlem, and the South Bronx, low-income areas with few parks and recreational facilities.

Sports and organized recreational activities can also have a positive impact on social and emotional development as well as educational achievement. Teens who participate in organized recreational activities are less likely to drink alcohol, take drugs, or get pregnant. In several cities, the availability of recreation for youths has been found to lower crime rates. In Fort Worth, Texas, for example, crime fell 28 percent within a one-mile radius of community centers offering midnight basketball, but rose an average of 39 percent around five other centers that did not have the program. Studies have also shown that students who participate in physical activity on a regular basis do better in school.

The Decline Of Recreation in New York City

Parks have traditionally played a major role in providing sports and other recreation to city dwellers, especially youth. Under the City Charter, the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation has the "power and duty" to build and operate recreational facilities and offer programs, as well as to review and coordinate recreational activities conducted by other city agencies and to make agreements with government or private organizations for that purpose.

Advocates say that the department has been hampered in this goal by inadequate funding and by the low priority that the city placed on recreation for many years.

For decades, New York City let its recreational infrastructure crumble, both in the parks and in the schools. Beginning in the mid-1970s, the city all but eliminated funding for school sports and lowered the priority of physical education and fitness in the schools. Until recently, most high school teams and coaches have had to fend for themselves on bumpy, litter-strewn fields, buying their own uniforms and equipment and scraping up cash for transportation.

New York City’s schools once produced a steady crop of athletes for the major leagues, but by the 1990s the city had the lowest percentage of students participating in team sports of all the nation’s big cities, according to a 1999 New York Times series, Dropping the Ball (in pdf format) .

During that time, funding to maintain the city’s parks, courts, and fields also declined, reaching a low after the fiscal problems of the early 1990s, when the city shuttered recreation centers and let baseball and soccer fields wear down to dirt and rocks. The city built almost no new recreational facilities between the 1970s and the 1990s. Data compiled by the Center for Park Excellence at the Trust for Public Land show that New York City has fewer recreation centers, pools, and tennis courts per capita than nearly every large city in the country.

Although things have improved tremendously over the last decade, there are still fields and courts that are not in good condition, especially in the smaller parks in the outer boroughs. The 2005 Report Card on Parks, an annual survey of neighborhood parks conducted by the advocacy group New Yorkers for Parks, graded 29 percent of athletic fields and 33 percent of courts unacceptable for maintenance work.

Sports on the Rebound

In recent years, the city has increased capital funding for building and restoring sports fields and other facilities. The private sector has also been pinch-hitting for the government, providing the energy, expertise, and funding to fill gaps in the city’s recreation network, particularly in the city’s poorer neighborhoods.

The parks department has fixed up soccer, baseball, and football fields all over the city. On more than 40 fields, it has replaced grass (or what was left of it) with more durable artificial turf, and plans to convert 35 more. "As fast as we can build them," said Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe, "they fill up, like building highways."

In April, the department inaugurated a $42 million track-and-field stadium on Randall’s Island, with half of the cost raised privately by the Randall’s Island Sports Foundation, including a $10 million naming sponsorship by financier Carl Icahn.

More new recreation centers have been opened or are in the works since the late 1960s or early 1970s, said Commissioner Benepe, who ticked off a list including the reopening of the Chelsea center after three decades; the near completion of another center in Flushing, Queens; the new nature center in the Staten Island Greenbelt; and the construction of a senior center in Marine Park.

If the city succeeds in its bid to play host to the 2012 Olympics, dozens of new facilities will be built or renovated, although there is debate about whether, when the Olympics are over, there will be enough demand for, and the city will be willing to maintain, such specialized venues as a shooting center, a whitewater course, and an enclosed bike track.

To meet some of the most pressing recreational needs of the city’s youth, a number of nonprofit groups have stepped up to the plate:

- Take the Field , founded in 2000 by three businessmen and philanthropists in response to the New York Times series about the decline of school sports, has rebuilt decrepit fields at 43 city high schools. The five-year effort, with $35 raised by Take the Field matched by $99 million from the Department of Education, is about to conclude after reaching the goal of fixing all the fields the group identified as in need of repair.

- In neighborhoods with the greatest need for parkland, the New York City Spaces program of the Trust for Public Land is taking the asphalt yards of elementary and middle school yards (some formerly used as parking lots) and turning them into multiple use parks. The yards, which have space for active sports, quiet activities and greenery, are open to the community outside of school hours. The organization has built 12 parks so far and recently entered into a $25 million agreement with the Department of Education to build 25 more, providing a quarter of the funding and overseeing the design and construction.

- New York Restoration Project, founded by Bette Midler to restore parks in disadvantaged neighborhoods, led the effort to transform a polluted site into a park at Swindler Cove on the Harlem River in Upper Manhattan. It also raised funds to build a floating boathouse anchored off the park, the first new community boathouse in the city in nearly 100 years. Rowing programs run by the group are introducing the Olympic sport to inner-city youths. The boathouse also provides a home for dozens of rowing teams from schools all over the city.

A Patchwork of Programs

The parks department has focused mainly on building and maintaining the infrastructure for sports, either directly or through concessions. Commissioner Benepe said, "The primary way we provide recreation is by creating facilities — clean, safe and well-run —that allow other groups to program them."

In the absence of a coordinated citywide recreation program, possibly hundreds of different organizations have developed programs to fill the gap, including volunteer sports leagues, neighborhood-based organizations, school and after-school programs, private non-profit groups, and profit-making recreational centers.

Per capita and as a percentage of its total budget, the New York City parks department spends less on programming (including sports, nature, art and other recreational activities) than most other major U.S. cities, according to data compiled by the Center for Park Excellence. According to the Independent Budget Office, in 2004 parks department recreation spending totaled just $16 million, out of an operating budget of approximately $260 million. Of that amount, about $9 million came from the state and federal governments and other city agencies and private sources. This does not include privately run recreation programs whose funding is not channeled through the parks department.

Funding for full-time recreation staff has fallen 69 percent since 1980, according to the parks advocacy group New Yorkers for Parks, although some of the difference has been made up by seasonal and temporary employees, including the job-training program workers who now make up the majority of the parks department work force.

Funding, Places and People All In Short Supply

Every year at budget time, there is uncertainty about funding for the playground associates, who keep the playgrounds clean and safe and organize activities in the summer. Typically, the mayor’s proposed budget reduces the number of positions for these and other seasonal workers and the City Council eventually restores them. At present, there are 171 playground associates for the city’s 991 playgrounds, according to the parks department.

"There’s a short supply not only of places to play but of people to supervise," said Maura Lout, research director at New Yorkers for Parks. The difficulty of getting a complete picture of recreation in the city because there are so many different providers, Lout said, "speaks to the dilemma."

Although some wealthier parts of the city, as well as formerly industrial areas like Tribeca, lack recreational fields and programs, residents in these neighborhoods tend to have the time and money to sign their children up for private classes and for sports leagues outside the immediate neighborhood. Some families in affluent areas of Brooklyn, for example, don’t think twice about enrolling their kids in a hockey program at the for-profit Chelsea Piers in Manhattan.

Targeting Poorer Neighborhoods

In large part because of the lack of facilities, the largest gaps in recreation programs are in the poorer neighborhoods with mostly minority or immigrant residents. In these areas, the cost, time and travel involved in getting to activities outside the immediate neighborhood are significant barriers to participation in many sports.

The parks department has made an effort to target its limited recreational resources to youth in these neighborhoods. Benepe noted that all of the department’s recreation programs for children, from swimming lessons to nature walks, are free.

The department organizes several athletic leagues and tournaments, often with support from corporate or non-profit partners. One innovative program directed toward underserved youth is the Star Track youth cycling and mentorship program in the newly renovated Kissena Velodrome in Queens. "Shape Up New York," a program run with the city health department, offers exercise for all ages at ten locations with high rates of high obesity and diabetes.

Free instruction in tennis, golf and track and field is also available at a number of parks from the City Parks Foundation, an independent non-profit that supports parks without access to private resources.

Working With The Schools

The parks department has also begun to coordinate its efforts with the Department of Education. "This is the first time in recent memory, maybe ever, that the parks and education departments are actually sitting down and talking to each other," said David Rivel, executive director of the City Parks Foundation.

Benepe said that with so many new schools being opened, the two departments have been discussing the use of park facilities during the day for physical education. They have also talked about expanding learn-to-swim programs using pools operated by both the schools and parks, as well as by colleges, non-profits and other organizations. "We could probably teach every kid how to swim if we put our minds to it," Benepe said. "If I could do one thing in the next four years it would be to teach every child, if not how to swim, at least to know what to do if you go in the water."

Under the leadership of Chancellor Joel Klein, there has been a new emphasis on fitness at the Department of Education. The department hired its first citywide director of fitness, Lori Benson; began providing professional development for physical education teachers; and instituted a new citywide physical education curriculum that emphasizes health-related fitness. With $1 million each from The Sports and Arts in Schools Foundation and the Snapple sponsorship, the department expanded a middle school sports and fitness program it piloted last year to 180 schools, many of which use parks for practice and games. "We are in the midst of a complete renaissance of the physical education program, which has not seen a lot of support over the last few decades," Benson said.

"There is a long way to go," said Rivel, "but things are clearly going in the right direction."

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Recycling

Related: |

Listening to Mayor Michael Bloomberg and New York City Council Speaker Gifford Miller fight over garbage this month, the casual observer could be forgiven for thinking that the mayor’s entire citywide plan for garbage centered on a single pier on the Upper East Side. The development of trash policy has recently gotten bogged down over the mayor’s call to use several such piers as places for garbage trucks to unload onto barges. The dispute reached a climax on June 22nd when Miller failed to block the opening of the so-called marine transfer station in his district.

But with this diversion out of the way, officials and environmental advocates are turning back to the central issues of a plan that is rich in details on how to move the city's trash around, but, critics say, short on everything else.

“It’s our hope that the controversy is over and we can get back to the overall business of this plan, which is how do we deal with the rest of this 50,000 tons per day of waste,” said Eddie Bautista of the Organization of Waterfront Neighborhoods.

In the past, the city has dealt with waste by burning it, or burying it. Now Bloomberg is focusing on shipping it away. But the City Council has published its own plan that lists recycling as its major priority, and criticizes the mayor’s plan for failing “to put forward any real programs or policies that would reduce waste and increase recycling.”

Councilmember Michael McMahon, head of the council’s sanitation committee, will soon begin negotiating with the mayor over the council’s concerns. His hope is that by September a compromise plan will be worked out -- and that it will prominently feature recycling.

ARE NEW YORKERS RECYCLERS?

In theory, increasing the amount of garbage that is recycled is a goal that everyone can agree on. But how to do so is not necessarily simple, and officials differ on how much recycling the city can reasonably expect.

Currently, about 20 percent of residential waste in New York is recycled. City life poses serious challenges for those planning ways to raise this rate. Most New Yorkers live in apartments where there is often little space to set up bins to separate garbage. And although residents are legally required to recycle, apartment-dwellers are relatively invulnerable to tough enforcement measures, because it’s hard to find out who in a large apartment building isn’t recycling in order to fine them.

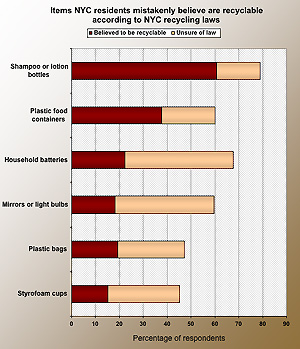

Further, many New Yorkers are confused about what is recyclable. A recent survey conducted for Gotham Gazette by Baruch College's eTownPanel found that about 85 percent of city residents knew that newspapers are recyclable, but less than half knew that aerosol cans are, and only about 40 percent knew that wire hangers are. At the opposite end, about 40 percent knew that plastic deli containers are NOT recyclable, and a mere 20 percent knew that they cannot recycle shampoo and lotion bottles. (For details on the survey and to see charts, click here)

Some believe that a mixture of education and enforcement could significantly raise the rate of recycling in the city, but Mayor Bloomberg is skeptical that these will make much difference.

“The more you recycle the better off you are,” he told WABC-FM earlier this month. “But most [of the city’s waste] is going to get thrown out.”

THE MAYOR’S ATTITUDE: SKEPTICAL OF RECYCLING

The mayor’s attitude towards recycling has displeased recycling advocates in the past. Facing a daunting budget gap in 2002, the mayor decided recycling was a luxury the city could not afford. The city suspended its glass and plastic recycling programs.

It wasn’t the first time that the city had cut back on recycling efforts in tough times. When the environmental benefits of recycling are measured against its economic drawbacks, the economics generally win out.

“Whenever something bad happens, recycling gets pushed back,” said Carmen Cognetta, legal counsel to the City Council’s solid waste committee.

Recycling has always been vulnerable to budget cuts because historically it has been more expensive that dumping garbage in landfills. While taking trash to a landfill costs significantly more than it does to take it to a recycling plant, the higher cost of collecting recyclables more than offsets these savings.

Advocates have long hoped to develop a way to make recycling as cheap as waste disposal. If achieved, this goal of “cost parity” does work to protect recycling programs. The city didn’t consider eliminating paper recycling in 2002, for instance, because it was actually getting paid by private companies for the recyclable paper, rather than having to pay.

THE MAYOR'S PLAN: MAKING RECYCLING PAY OFF

The mayor's overall garbage plan calls for the city to load its waste onto rail and barges and ship it out of the city, instead of relying as heavily on trucks as the city does now.

Environmentalists and activists from low- income neighborhoods have thrown their support behind the plan, because it decreases the city’s reliance on trucks, and spreads the burden of waste management throughout the city. The main criticism of the plan has been that it does not address where to send the trash, thus doing little to deal with the city’s fundamental trash related problem: its reliance on increasingly pricey landfills in distant places. (report in .pdf format)

For recyclables, however, Bloomberg’s plan does identify what it says is a good place to send waste. The city has forged a long-term relationship with recycling company Hugo Neu, in order to secure stable, favorable rates. As incentive to sign the 20-year contract, the city has agreed to invest $25 million to help Hugo Neu build a recycling facility in Sunset Park. Savings from the terms of the contract, the city believes, will more than offset the cost of the plant.

As the cost of recycling decreases, the cost of waste disposal will be increasing, thanks to the capital investment necessary to make the transition to new forms of transportation. This, some see as a good thing.

“This short-run increase in waste disposal costs, coupled with a new contract that lowers the fee paid for processing the city’s recyclables, alters the economics of waste management increasingly in favor of recycling as a cost-competitive alternative to disposal,” wrote Elisabeth Franklin and Preston Niblack of the Independent Budget Office in a recent analysis. (report in pdf format)

The analysis concludes that, all things being equal, the mayor’s plan will make the cost of recycling roughly equal to that of waste disposal.

While Bloomberg’s plan may end up creating a strong financial incentive to recycle, critics still deride its lack of a coherent recycling strategy.

"Exporting trash is one little piece of solid waste management. The city has a golden opportunity to commit in writing to innovative waste prevention, reuse, and recycling initiatives,” said Majorie Clarke, co-chair of the New York City Waste Prevention Coalition. “That's the guts that they're missing."

THE CITY COUNCIL’S ALTERNATIVE

Are New Yorkers Recyclers? Click here for details and charts |

The City Council aims much higher than the mayor in terms of recycling. Bloomberg’s goal is to have 26 percent of residential waste be recycled by 2010 and a 33 percent residential recycling rate by 2024. The council plan is much more ambitious, calling for an increase in residential recycling from 20 to 25 percent by 2007, and by 2015 a combined residential and commercial recycling rate of 70 percent.

Increasing recycling rates not only has environmental benefits, it has economic advantages as well. The more residents can be taught what is recyclable -- and either encouraged or forced to do it -- the cheaper recycling becomes. Collecting garbage is less expensive than recycling because the same truck can gather more tons of garbage per route than it can of recyclables. This is partially due to the relatively low weight of recyclables – plastic weighs less than food waste. But the more recycling that ends up on each curb, the less it costs to collect each ton of it.

“If the city is successful in increasing recycling beyond recent levels, it may even become the cheaper alternative, creating a strong incentive to promote recycling as a way to hold down the total cost of waste management,” wrote Franklin of the Independent Budget Office. (report in pdf format)

The mayor’s plan brushes over this potential; there are few specific ideas for increasing recycling rates. By contrast, the council’s plan calls for establishing a division in every community board that will tailor recycling programs to the local level. A new city agency would oversee this, leaving the Sanitation Department – which proponents of the plan describe as insufficiently committed to recycling – out of all recycling education and outreach programs.

"[Recycling] is never going to flourish under Sanitation," said Cognetta.

But Benjamin Miller, former director (and current critic) of policy planning for the Sanitation Department and author of Fat of the Land, a history of the city’s garbage, doubts whether the council’s plan will be effective. Any recycling plan should set a single standard for the entire city, he says, rather than relying on individual efforts in each neighborhood. And the best way to have a citywide plan is to keep a single agency in charge of all waste issues.

“The plan proposes what I would argue are likely to be quite inefficient systems [that] reflect a flawed understanding of how a recycling system should be designed,” he said. “We have to keep it simple.” Miller believes the best way to increase recycling is to charge people for the amount of garbage they throw out, creating an incentive to reduce the amount of waste they produce by, for example, recycling more.

The council’s plan also calls for increasing commercial recycling rates, and attempts to establish ways to recycle or reuse materials that today tend to end up in landfills.

ZERO WASTE: BEYOND RECYCLING

Some of these strategies were discussed at a recent conference of recycling advocates held in downtown Manhattan. The conference’s focus was to formulate programs that go beyond recycling by increasing the scope of what can be recycled and reduce consumption in general in a comprehensive strategy.

Attendees noted the success of initiatives in California and Maine that reduced waste at the source. They suggested more aggressive citywide compost recycling and a surcharge on plastic bags. A similar “plastax” law in Ireland reduced plastic bag use there by 90 percent.

The city would need help in implementing some of these ideas. Any new tax, for instance, would need to be approved by Albany.

The council has embraced these principles as part of its plan. It is currently considering several actions, including a bill that would require manufacturers to take back and recycle, reuse or properly dispose of a percentage of the electronics they sell. Another resolution calls on the state to pass a bill that would expand the bottle deposit to more products.

Jordan Barowitz, a spokesperson for the mayor, told the New York Times that the administration is willing to consider substantive changes to its plan, and specifically cited adding measures to increase recycling. But council’s plan, he said, was “a gimmick. It doesn’t advance the negotiations at all.”

Garbage plans in New York are often written and rarely implemented, and there is no guarantee that the council and the mayor’s negotiations this summer will end up producing anything resembling either of their plans. But if the officials can navigate the ever-tricky politics of garbage, recycling advocates see the potential for an economic and environmental payoff in the ideas currently on the table.

Â

Are New Yorkers Recyclers? A Survey of Habits and Attitudes

Eighty-two percent of New Yorkers say that they recycle “almost always” or “most of the time” at home, according to a survey conducted by Baruch College's eTownPanel for Gotham Gazette this month. Only five percent say that they never recycle. Fifty-six percent said they recycle more now than they did five years ago.

But they also express confusion about what they can and cannot recycle. While 83 percent of respondents knew they could recycle newspapers, only 40 percent knew that wire hangers were recyclable, and less than half knew that aerosol cans were recyclable. Only 62 percent said they were either “very familiar” or “familiar” with the city’s recycling program overall, and 15 percent said they were “not familiar at all.”

Respondents seemed to see their own confusion as a result of the city’s poor performance in educating its residents about the recycling regulations. Sixty-six percent said that the government’s performance in education the public was either “fair” or “poor”. They were also skeptical of the government’s commitment. Over half of respondents said that the city was only “somewhat committed” or “not committed at all” to recycling, while only 11 percent felt the city was “very committed”.

The survey was conducted betweeen June 7 and June 14, 2005 of 150 New Yorkers.

Return to Recycling by Sam Williams and Joshua Brustein

Â

The Same Old Budget Game

With a surplus in city revenues, Mayor Michael Bloomberg is handing out goodies to a number of constituencies in his election-year budget. But for the parks department, it’s another year on a low-calorie diet.

Although in recent years New York City has increased its capital expenditures for renovating old parks and creating new ones, it spends less per capita on maintaining and operating parks than most major U.S. cities. In 2003, the city spent $32 per resident, compared to an average of $60 per resident in 36 major U.S. cities, according to the Center for Park Excellence at the Trust for Public Land.

Most observers agree that the parks department does a good job with limited resources. In addition, private funding has helped transform Central Park and others into green gems and continues to pay for the gardeners and other workers who keep them that way. But especially in the outer boroughs, many parks have worn grass and patchy plantings, locked or broken bathrooms, dusty and littered playing fields.

In its 2004 independent assessment of conditions at small neighborhood parks, The Report Card on Parks, the parks advocacy group New Yorkers for Parks gave almost a quarter of city parks a failing grade. It found that more than half the bathrooms were either closed or dirty and unsafe, 27 percent of the athletic fields were unacceptably maintained, and half of the sitting areas were littered, among other things.

The decline in funding over the last two decades has most affected the fulltime parks staff, which has decreased 60 percent in the last two decades. Most maintenance is now done by roving crews of temporary workers enrolled in a job-training program funded through the Human Resources Administration. Few parks have a staff person -- a "parkie" -- assigned to their care the way they once did, someone with a responsibility for that park and a relationship with its community. The department has also reduced the number of skilled workers, like gardeners, tree pruners, and plumbers. The 2005 budget, for example, funded for just 12 plumbers citywide -- one for every 53 bathrooms, 159 water fountains and 5 pools.

The Same Old Budget Game

Mayor Bloomberg’s proposed operating budget for parks this year is essentially the same as last year. Actual city funding is $196 million, down slightly from last year’s $201 million. The executive budget once again proposes eliminating the entire street tree pruning program, as well as $7.3 million for about 600 seasonal workers; the three previous budgets have done the same thing, though the City Council usually restores both items, at least in part.

"It’s the same song and dance we have every year," said Maura Lout, research director at New Yorkers for Parks. "The mayor cuts the budget with the understanding that the Council will restore it. It really prevents us from taking the step we need, which is enhanced resources for the parks department."

The budget adds some new funding, however, for staffing at the 54th Street Recreation Center and the new park at Fort Totten, as well as for fighting the Asian longhorn beetle. In addition to the $197 million in city operating funds, there are interagency transfers of $42 million, about the same as last year, for workers in the job training program; $20 million for staff overseeing capital projects; and $5 million in federal block grant funding.

A Promise Unfulfilled

During the 2001 election campaign, in response to grassroots lobbying organized by New Yorkers for Parks, Mayor Bloomberg and a number of City Council members pledged to increase parks funding to one percent of the city budget.

After September 11th and the fiscal difficulties that followed, funding for parks was cut, along with that for other city agencies. In the last couple of years, funding has returned to the levels of the 1990s, around half a percent.

But parks advocates are crying foul now that the mayor has a surplus that he is willing to spend. "While it’s a great budget for many city agencies, it’s not a great budget for parks. We’re waiting for a restoration and an increase after decades of cuts," said Lout of New Yorkers for Parks.

As the 2005 election approaches, park advocates have begun a new effort to get a commitment from candidates for greater park funding. In its Parks 1 campaign, New Yorkers for Parks is asking candidates again to pledge to work toward allocating one percent of the city budget to parks.

As a specific first step, it is asking them to support legislation allowing the parks department to keep the roughly $40 million it gets in revenue from concessions such as restaurants, golf courses, and hot dog stands, in addition to its regular city funding. "It’s very easy for candidates and elected officials to say they are pro-park, but it is very easy not to put any muscle behind it," said Justin Krebs, campaign director of Parks1.

Many other cities direct parks-generated revenue back to the parks. Some park supporters oppose the idea, however, warning that it would tempt the city to cut funding further and would result in greater commercialization of the parks.

Will advocates have more success this time in increasing resources for the parks? With other essential city services, like education and transportation, also in need of greater funding, it is easy for elected officials to continue to view parks as a luxury, far down on the list of priorities. The city has also turned increasingly to the private sector to take on the responsibility of caring for the parks. The cities with the best-maintained park systems often have some type of funding mechanism specifically for parks, unlike New York City, where park funding is at the mercy of the annual budget process and politics.

Yet the constituency for parks is getting larger, in tandem with the growing number of people contributing time and money to their local park. In April, 500 park and community garden supporters spent the day visiting the offices of City Council members. They came from all five boroughs to air concerns about their neighborhood parks and to ask for increased funding for parks.

More than half of the City Council members have signed the pledge, along with Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum and Queens Borough President Helen Marshall. So far, Mayor Bloomberg has not taken a position, although according to New York Metro, the free daily, his spokesman Jordan Barowitz said, "The Parks Department deserves every penny that the city can afford, but unless you identify a new source of revenue, that money from concessions is used to educate our children, pay our police officers and build affordable housing."

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.Â

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.Â

Putting A Price On Street Trees

How many trees are there on New York City streets?

That question will be answered this summer by some thousand volunteers in a project called "Trees Count." Aside from counting every tree, the volunteers will collect basic data on each tree's location and species; they will also use handheld computers donated by Hewlett Packard to measure the diameter of the trunk and the crown.

All this data will be entered into a common database, then run through an economic model to determine not just how much it would cost to replace each tree, but also to assess how much each individual tree is worth.

"No one has really placed a value yet on the urban forest," said Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe. "This will help us do that."

In a city that just earned yet another set of failing marks for air quality from the American Lung Association, parks managers are eager to quantify to the penny how New York City street trees improve the air and diminish energy consumption.

The first tree census in the city, conducted in 1995, came up with a total just under 500,000 trees.

Officials estimate that the number this time around will be about the same. This is true even in the face of a short-term reduction in the local tree population. Noting the recent discovery of an Asian longhorn beetle eggs, Parks Commissioner Benepe promised an "aggressive" response. "Any trees found to have insects will be chopped down, chipped, and the chips will be sent to the incinerator," he said.

Such promises reflect the management philosophy that, in an era of diminishing budget resources, it's better to amputate and be safe than waste precious time and resources developing a more nuanced approach. One reason for the tree census, notes Jennifer Greenfeld, director of the New York Tree Trust, is to give future resource managers a clearer picture of what corners of the city are doing well and what corners aren't.

"[A census] helps us figure out how to balance our resources, how to adjust our palette in terms of how we respond to different problems ," says Greenfeld. "This is the one thing that helps give us a snapshot so we can plan what to do."

Although the 1995 tree census took note of tree condition, this year's count will take more notes on the types of things that lead to the biggest maintenance headaches -- things like powerline and sidewalk interference and the tree guards which protect trees over the short term but can restrict growth over the long term. Losing larger, more established trees to such problems is especially painful from a management perspective, Greenfeld says, because larger trees provide exponentially more shade, oxygen and pollution-filtering power than their sapling replacements.

"A tree is probably the only investment that a city makes that increases over time," Greenfeld says. "Unlike a sewer line, which gets less useful the older it gets, you want to keep [a tree] in the ground as long as possible."

To help prove that point, New York Tree Trust will be relying on an economic model developed by the Center for Urban Forest Research, a laboratory at the University of California at Davis that is funded by the U.S. Forest Service. Dubbed STRATUM, the model estimates growth rates by species and location and then multiplies the resulting size estimates with biological data and economic estimates on the social cost of airborne pollution and energy production. The end result, says center director Greg McPherson, is a bottom line summary of each tree's ability to reduce carbon, pollution, and energy bills over time.

"It provides the other side of the equation which is that trees are an investment," says McPherson. "If you increase your investment, you can provide yourself more of a return over time."

McPherson's lab has analyzed census data from cities such as Berkeley, Calif., Minneapolis, and Bismarck, N.D. Estimates on the "return on investment" for each tree planting vary by city. In Berkeley, the return on every dollar spent was $1.37. In Bismarck, the return was $3.09 for every dollar spent.

New York has tried to assess its trees before, in a 2001 study that concluded that urban trees statewide had a compensatory value of $84 billion and a carbon storage value of $500 million. David Nowak, lead author of the 2001 study, says pricing models are popping up in court cases to assess the value of damaged trees or stolen timber and could lead to even more creative uses. Last year, for example, the Office of the New York Attorney General mandated $47,000 worth of tree planting in a January, 2004, settlement with four school bus companies accused of excessive idling, one of the first attempts by a government agency to include trees in the bargaining process on air pollution.

Nowak expects this trend to continue, noting that trees are a classic example of a benefit enjoyed by society as a whole coming at a cost only to the individual or agency that planted the tree. This is the exact opposite of air pollution, which comes at no cost to the factories or automobiles, etc. that produce it, but produce damage felt by society as a whole. Economists call the first example, the tree, a "positive externality," and the second, the pollution, a "negative externality." Both are "external" to the ordinary marketplace's ability to set a price. Assessing the damage or benefits often falls on state agencies.

"A lot of things we can't quantify yet, but some of the things we can," says Nowak.

The Trees Count project was launched with an Arbor Day tree planting ceremony outside the Little Sister of the Assumption Family Health Service in Spanish Harlem, a neighborhood currently experiencing the highest childhood asthma rates in the country. According to a 2003 study involving researchers from Columbia University and Harlem Hospital, a quarter of all children in east Harlem suffer from asthma, more than four times the national rate. Looking past the current tree census, both Benepe and Greenfeld point to Trees for Public Health, managed by the Hunts Point environmental group Greening for Breathing.

Trees for Public Health seeks to reduce local air pollution levels in a corner of the city plagued by automobile exhaust and has, to date, relied on a patchwork funding from city, state, and federal agencies. One way to guarantee a steady stream of funding, Benepe says, would be to confirm a direct causal link between money spent on trees and money saved at local asthma treatment centers thanks to declining admissions.

"We've gotten to the point where people understand anecdotally why urban trees are valuable," says Benepe. "Our next step is to quantify that value. For that we need the help of the scientific community."

The 2005 Trees Count project starts on June 1, 2005. Volunteers who would like to help out can register by calling 311 or visiting the city's "Trees Count" web page. The Parks Dept. is asking volunteers to donate at least 40 hours of their time, plus a three hour training session. The training sessions begin in the second weekend of May. Event sponsor Bank of America, meanwhile, is offering $1,000 to the adult New York City resident who comes closest to guessing the final street tree tally. The free entry form, which requires physical address and birthdate, is located here.

Historic Preservation in NYC

Forty years ago this week, Mayor Robert Wagner signed a bill establishing the landmarks law and forming the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

The legislation and new city agency were created in response to a growing concern about the loss of historically, culturally, and architecturally significant places like Pennsylvania Station, which was demolished in 1963. To date, the commission has designated 1,119 individual landmarks and 83 historic districts, totaling 23,000 buildings.

But some argue that the landmarks law is not living up to its promise and much more must be done to save the city’s historic places.

Some buildings are threatened by new development. Other structures are at risk because owners do not have the financial resources - or refuse to spend the money - needed to maintain them. Decisions about the future of other sites are stalled by local politics.

“While 40 years of landmark preservation is indeed cause for celebration, many preservationists are not in any mood to pop open the champagne,” Kate Wood of the group Landmarks West wrote in an article for Gotham Gazette.

Here are ten sites in New York City – buildings, houses, churces, a shipyard, and even a swimming pool – that preservation groups are trying to save for future generations of New Yorkers.

Â

Trees & Sidewalks Repair Program

In a small but significant step forward for both street trees and public safety, the city has begun a $3.4 million pilot program to fix sidewalks that have been damaged by tree roots, at no cost to the homeowner. The program is targeted to owners of one-, two-, and three-family houses.

Previously, the owner of the property next to the unsafe sidewalk would be issued a violation by the city Department of Transportation and was responsible for the repair. Although the parks department would take care of trimming the roots, the homeowner had to arrange for a contractor to remove the old sidewalk and put in a new one, at a cost of around $1,000.

"I have reams of letters from homeowners, some anguished and some angry, lamenting the unfairness of having to repair a sidewalk when the damage was caused by a publicly owned tree, in many cases planted by the city," said Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe. "It was creating a great deal of frustration and anger toward the city and trees."

Under the new Trees & Sidewalks Repair Program, all homeowners have to do is call 311. The parks department will come up with a solution to the safety problem that also protects the health of the tree. Potential repairs include expanding the pit, especially on lightly traveled sidewalks; slightly raising the level of the sidewalk to go over the roots; or strengthening the flags. Top priority will be given to sidewalks with the most severe damage, with a larger percentage of the pathway affected, and with the highest levels of pedestrian traffic. The transportation department will continue to conduct inspections and issue violations, but will notify the parks department when violations appear to be caused by trees.

Good For The Trees, Good For The Bottom Line

Although for years the city was reluctant to allocate money for fixing root-damaged sidewalks, over the long term, it could prove to be a smart investment. It should lead to safer sidewalks, fewer people falling, and a reduction in lawsuits against the city. Until last year, when the city passed a law making property owners liable for injuries that occur on sidewalks in front of their buildings, the city spent about $20 million a year on lawsuits by people who tripped and fell on sidewalks, according to Kate O’Brien Ahlers of the New York City Law Department. Although claims have dropped 30 to 40 percent since the passage of the new law, it does not cover owners of one-, two-, and three-family houses, to whom the sidewalk repair program is targeted.

The program is also expected to enhance the health of the urban forest, boosting its value both in economic terms and to the city’s quality of life. It costs $1.110 to replace a street tree and, with the worth of a street tree with a 3-foot-wide trunk roughly $10,000, every tree that thrives helps the bottom line. That does not include the real (if not easily quantifiable) value of trees in filtering pollutants, reducing energy costs, and raising real estate values, to list just a few of the benefits. For example, a study by U.S.D.A. scientist David J. Nowak estimated that in 2000, New York City’s street trees reduced 1,500 tons of pollutants at an associated value of $8 million.

Conditions are difficult to begin with for the city’s half million street trees, which live in a hotter, drier, and more dangerous environment than their park counterparts. Historically, the city has provided minimal funding for maintaining the trees, and only for pruning. The frequency of street tree pruning was increased in 1997, but funding for pruning is one of the first things to be cut when budgets are tight. The city depends on citizens and nonprofits like TreesNY for other essential care, such as watering, cultivating the soil, monitoring for disease and insects, and putting up tree guards .

By having the parks department oversee the repairs, the new program will make sure that they are done with greater sensitivity to the health of the tree. And homeowners dealing with cracked and raised sidewalks will view street trees as less of a nuisance.

The program was funded in part by the borough presidents of Queens, Staten Island, and the Bronx. "It is a program we would like to see work and become permanent," said Dan Andrews, speaking for Queens Borough President Helen Marshall, noting that Queens has the most street trees of any borough.

Judging from the number of requests for sidewalk repairs in the first two days after the program was announced -- nearly 1,500, half the number of root-trimming requests the department received in an entire year in the past — there is a huge pent-up demand.

"It’s one of the extremely gratifying common-sense things that we’ve all wanted to do for years," Benepe said. "It will do more to improve both the survival rates of street trees and homeowners’ relationship to street trees than anything else we could have done."

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.Â

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.Â

The Politics of Parking

|

Related In Community Gazettes: |

Tavi Fields, a 25-year-old rapper, found the city's alternate side parking regulations more than she could handle. "I was going through a hard period of time for a while, where I slept in for most of the day," Fields told the Daily News. While she stayed in bed, her Lexis remained on the wrong side of the street. The result: 90 tickets now totaling $10,433, making her, by the paper's reckoning, one of the top 10 parking scofflaws in the city.

Most New Yorkers manage to avoid such a dubious distinction, but for the people who own the 1.9 million cars registered in the city, parking borders on an obsession. Its rules have spawned at least one novel, a guidebook, sitcom episodes, and two companies dedicated to helping New Yorkers outsmart traffic enforcement officers.

Parking presents elected officials with a quandary. Many New Yorkers with cars view a free space to park as a God-given right. But other New Yorkers, pointing to pollution and congestion from automobiles, object to any move that encourages driving. The city's need for revenue from parking further complicates the picture, along with politicians' natural reluctance to attract the ire of voters who get tickets.

These issues arise again and again - in the controversies over parking at the West Side stadium and the proposed Nets arena in Brooklyn and the debates over the future of city neighborhoods. (See related stories on Flushing and Bay Ridge.) The latest imbroglio is an election year tiff over the use of parking meters on Sunday, which the mayor's critic dubbed "pay to pray."

Most New Yorkers would say the problem is too many cars chasing too few spaces. But some planners disagree. The problem, they say, is not that parking is too expensive, but that it is too cheap. And some say the problem is not that there are too few spaces but that there are too many.

THE HIGH COSTS OF CRUISING

Paying for space in a parking garage, George tells Elaine as they seek a space on an episode of Seinfeld, "is like going to a prostitute. Why should I pay when, if I apply myself, maybe I could get it for free?"

Many New Yorkers apparently agree, and so spend long periods of time driving, in concentric circles or zigzags, looking for parking.

Even the smartest among us do this silly chore. In a 2000 interview, Horst Stormer, a Nobel Prize winner in physics, described his formula for finding parking spaces by scooting ahead of rival drivers.

The average cruising time for a parking space in some New York neighborhoods approaches 14 minutes, according to a 1993 study. That's twice the time spent in San Francisco, where it is so hard to park that residents leave their cars on the sidewalk.

But cruising takes up more than time. Environmentalists cite a 1984 study that found drivers in one 15-block neighborhood in Los Angeles spent 100,000 hours cruising, wasting 47,000 gallons of fuel and producing 700 tons of carbon dioxide emissions in a single year.

New York's rules complicate the process. Moving the car from one side of the street to the other is not required in every city. And any single spot can have three sets of rules governing its use at various times.

Such parking regulations attempt to address a variety of needs, according to Michael Primeggia, the Department of Transportation's deputy commissioner for traffic operations. In most of the city, the main concern is street cleaning, which dictates the alternate side rules.

But in busier commercial areas, particularly in Manhattan, other considerations come into play, such as the need to accommodate traffic flow and allow for deliveries. "New York City is not so lucky that there can be one regulation that regulates the curb for the entire day," Primeggia said. And that leads to two or three signs - with different rules - for a single space.

A WALKER'S CITY, DAMAGED BY PARKING

Ironically, the city famed for its convoluted parking rules and parking headaches is the only American city where a majority of residents do not own cars. This gives rise to a chicken and egg debate. Do New Yorkers not own cars because it is so hard to park? Or is it so hard to park because New York remains a pedestrian and mass transit city that has not destroyed itself to accommodate the automobile?

The number of cars registered to New Yorkers has declined by about 5 percent since its peak in 2000. According to the 2000 Census, 54 percent of all New Yorkers -- and three out of four Manhattan residents -- do not own a vehicle.

But cars still clog Manhattan streets. Although the number of auto trips into Manhattan dropped after September 11, 2001, it has begun to grow again. Some experts predict it could reach 1 million vehicles a day.

A majority of people in Brooklyn and the Bronx do not have cars, but two out of every three Queens residents and four out of five Staten Islanders do.

By some measures (.pdf format) , New York is the second most congested - after Los Angeles - of America's largest cities. In 1990, the average speed of crosstown traffic in a car fell to 5.2 miles per hour. Brian Ketcham, a Brooklyn transportation consultant, estimated then that traffic cost the city nearly $30 billion a year in losses in employee productivity, accidents, air pollution, noise and roadway damage. And a 2004 study concludes that congestion cost the metropolitan area more than $7 billion in wasted time and fuel alone.

HALF A BILLION DOLLARS OF PARKING TICKETS

Many New Yorkers decide not to own a car at least because parking costs so much - particularly for drivers who get a lot of tickets. City drivers paid $537 million for parking violations in 2004. This came from some 10 million tickets, a 20 percent increase from 2003.

Primeggia says parking regulations are not designed to produce revenue or to confuse drivers. Any average citizen who reads English should be able to figure where and where not to park. When there is more than one sign applying to a space, the city puts the most restrictive sign on top. "All it takes is reading the signs in order and determining which sign is in effect," Primeggia said

But not everyone agrees. Louis Camporeale said he became aware of the faulty enforcement of traffic regulations in the 1980s. As a student, he would try to park at broken meters. "Three or four dollars in meter money was a couple of hours work," he recalled.

But sometimes the plan backfired, and he got a ticket -- an unfair ticket. (You can park at a broken meter -- but only for an hour.)

Such disputes led Camporeale to become an advocate for New York City parkers. He has written "The New York City Motorist's Guide to Parking" and runs a web site www.parkingpal.com with parking tips. "New Yorkers think they're so savvy, but when it comes to parking regulations, they're not," he said.

Glen Bolofsky, the author of the city's first alternate side parking calendar, now runs a business www.parkingticket.com that fights people's tickets - for a fee. Its successful challenges arise from confusing signs, mistakes on the ticket itself and other gaffes by the city. The company, which also operates in Boston, San Francisco, the District of Columbia and Philadelphia, claims that it won dismissals or reductions on 75 percent of the tickets it challenged last year.

"The rules and regulation are pretty much stacked against the average person," Bolofsky said. "The city goes out of its way to create a situation to intimidate and bully people."

Although the city consistently denies setting quotas for parking agents, Bolofsky disagrees. "The city budget dictates what the revenue [from parking tickets] is going to be," he said.

THE DEMISE OF THE PARKING LOT

People risk tickets to park on the street, though, because lots and garages cost so much - and the fees seem likely to rise even higher.

A reserved space in a garage in midtown cost $496 in 2004, the highest rate in the country, according to a recent survey. This has prompted some developers to offer parking condos where people purchase a space for tens of thousands of dollars and then pay a monthly fee.

But, despite this, lots are closing as New York's real estate boom makes land too expensive to park on. The city owns lots, but when the land becomes valuable, sells them for other uses. (See related story on Flushing.)

The same thing is happening with private lots. Broker Anne De Marzo told the New York Times that she has sold five parking lots and two garages in the Hudson Yards area with 20 more deals in the works. And Sean Sweeney, director of the civic group SoHo Alliance said he counted 2,000 parking spaces that had been lost in his area. Owners say they can sell their property for $350 for each "buildable" square foot.

POLITICS AND PARKING

In Calvin Trillin's novel about parking - "Tepper Isn't Going Out" –fictional Mayor Frank "Il Duce" Ducavelli sees his poll numbers rise after he goes after the "scofflaws in striped pants" - Ukrainian diplomats who did not pay their parking fees. Trillin obviously drew his inspiration from Mayor Rudy Giuliani's attacks on United Nations diplomats who parked illegally and used diplomatic immunity to avoid paying their tickets. While the problem has eased, New Yorkers still hold a special animosity for foreigners who park freely and illegally, and politicians continue to use that sentiment to their advantage.

Similarly, because alternate side parking rules have few fans among voters, City Council has added to the list of days when rules are suspended, aiming the dispensations at various religions and ethnic groups. In 2002, for example, the council voted unanimously to suspend rules on Asian Lunar New Year, Purim and Ash Wednesday, overriding the mayor's veto.

This year's political parking dispute concerns the use of meters on Sundays -- something the city has done in recognition, it says, of the fact that stores now stay open on Sunday. The move also brings in about $7 million a year.

But a Bay Ridge minister complained that parishioners were ducking out during services to feed the meters. In response, City Councilmembers Vincent Gentile and Hiram Monserrate introduced a bill that would ban metered parking on Sunday. (See related story)

Other Democrats picked up the cause. "There shouldn't be a tax on worshipping," mayoral candidate Fernando Ferrer said. "People shouldn't have to pay to pray."

The city has done a done a few things on parking that have met with general approval, particularly the use of multiple space meters. Rather than feed coins into a metal meter on a post, motorists purchase a ticket from a machine and then leave it on their dashboard. Cars can then park more tightly. The system also enables the city to charge different prices at different times or discourage long stays.

Currently, Primeggia said, many of the meters charge $2 for one hour but $9 for three hours to spur turnover. "We're encouraging them to use it as long as they need it, but when they're done leave," he said.

The city also addresses parking in zoning decisions. Residents often cite increased parking difficulties as a hallmark of rapidly developing - or overdeveloped - neighborhoods. So, on Staten Island, for example, the city has increased requirements for parking to accompany new buildings. Of course, more space for parking can mean less land for other uses, including lawns and gardens.

PARKING AND NEW PROJECTS

Concerns about parking also enter into one of the year's hottest political controversies: the proposed Jets stadium on the Far West Side. The extension of the No. 7 subway line aims to make the proposed West Side football stadium friendly to transit users and discourage automobile use. The Jets anticipate 70 percent of people attending games will arrive by mass transit. This would require parking for 7,000 cars.

And an anti stadium group, the New York Association for Better Choices, sees that number as unrealistic. It predicts that each Jets game would attract 16,000 cars and 100 buses, requiring 70 acres of parking lots and garages.

For the short term, the city has said it plans to allow approximately 1,500 new spaces near the railyards. Eventually, it says, thousands of new parking spaces would be provided to accommodate the residential and commercial development of the surrounding area.

Parking is also a concern for the Nets arena in Brooklyn, which, like the Jets Stadium, aims to be accessible by mass transit. The arena plans call for 3,000 parking spaces but critics say this will not be enough. And, they charge, an already congested area will grow more crowded as thousands of Nets fans cruise the streets looking for parking.

Parking is such a problem for new projects that developers want even racecar fans to get out of their cars. The proposed NASCAR track on Staten Island would accommodate about 95,000 people, but the plan only calls for parking for 8,400 cars. International Speedway Corp. hopes fans will park at some 16 off-site lots and take shuttle buses to the track.

PAYING TO PARK

Even though parking is a cherished commodity in New York, the city gives it away. A 2002 survey found that only 24 percent of the almost 30,000 curbside parking spaces in Manhattan south of 59th Street had meters.

Donald Shoup, a professor at University of California Los Angeles, argues in his new book "The High Cost of Free Parking" that free parking creates many costs, helping to explain "extreme auto dependence, rapid urban sprawl and extravagant energy use." Just charging $1 an hour for those unmetered Manhattan spaces, he said, would generate $250 million a year.

"People are paying a very high cost for housing and people even go homeless and cars are parking for free," he said.

Shoup believes the city should set rates for on-street parking high enough so that about 15 percent of the spaces are usually unoccupied. In some areas of London, this is eight pounds -- about $15 -- an hour.

To make such a sharp increase in rates politically palatable, Shoup proposes the money go to local community agencies to fund neighborhood improvements. "Nobody ever wants to pay for parking, so you have to create someone on the other side of the meter who wants the money," he said.

Some critics say such policies are unfair to lower income people. And while this is less true in New York City than other places, businesses worry (.pdf format) that high priced parking will keep people from driving to their establishments and spending money.

Some cities, though, have taken more drastic measures to stop parking. Copenhagen for example has a policy to reduce parking by about two percent a year.

That would be fine with Kit Hodge, campaign director of Transportation Alternatives, as long as people take transit, bike or walk instead. "Our aim is to discourage parking," she said.

For More Information

Organizations

New York City Department of Transportation

Alternate side parking, other parking regulations and how to pay a ticket online.

Parking Pal

Information and tips designed to help drivers park in New York City

Transportation Alternatives

An advocacy groups that seeks to reduce automobile use. Its web site includes information on car and bicycle parking.

Resources

Colliers Parking Rate Survey (in pdf format)

A survey of how much it costs to park in 55 North American cities.

Gridlock Sam

Web site run by former New York City Traffic Commissioner Sam Schwartz with information on parking, driving and congestion in the city.

parkingticket.com

Company that will fight your parking ticket - for a fee.

2004 Urban Mobility Study

The Texas Transportation Institute's study of mobility and traffic congestion on freeways and major streets in 85 cities.

Articles

The Autonomist Manifesto (Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Road)

(New York Times Magazine)

A Brief History of Parking: The Life and After-life of Paving the Planet

(Architecture Magazine)

The Dynamics of On-Street Parking in Large Central Cities

(Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management, NYU)

Fewer Cars (Same Traffic)

(Gotham Gazette)

The High Cost of Free Parking

(Donald Shoup)

The site includes the book's first chapter, articles on the book and comments by the author.

High Costs Drive Car Owners Crazy

(Daily News)

NYC Parking Policy is Backwards and Dangerous

(Transporation Alternatives magazine)

No Parking. You're Welcome

(New York Times)

The Overdevelopment Debate

(Gotham Gazette)

Parking Space and Public Spaces: Why Parking Can Destroy Communities and How to Find a Place for It

(Project for Public Spaces)

The Savvy Parker

(New York Chapter, American Automobile Associatin)

Shakedown: Sometimes It's the Little Things that Drive Your Over the Edge

"Tepper Isn't Going Out" by Calvin Trillin

(Salon)

Discusses the novel about parking in New York

Ticketing Blitz?

(Gotham Gazette)