The Battle for Comptroller

“One of the great strengths of the comptroller’s office,” former State Comptroller Alan Hevesi once said, “is that nobody has any idea what we do.”

While the comptroller usually gets little public and media attention, in the last few months, Hevesi, Governor Eliot Spitzer and Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver have unintentionally done much to change that. New Yorkers who may have paid little attention when Hevesi oversaw employee pension funds or audited the New York City school system to determine if it improperly spent some of its state aid, did notice when he become embroiled in a scandal involving his use of a state employee as a personal servant to his ailing wife. After months of controversy, Hevesi, fresh from a re-election victory, pleaded guilty to a felony and resigned.

Then, Spitzer and Silver, bolstered by many Assembly members, clashed over who should replace Hevesi. The decision now lies with the legislature, which is debating what to do. And so, as Spitzer announced his new budget last week, the post of the state’s fiscal monitor, who must review that budget and certify that it is balanced, stood vacant.

WHAT THE COMPTROLLER DOES

While the political battle over Hevesi’s successor may seem arcane, the comptroller wields extraordinary authority. With a staff of about 2,400 people, the comptroller has responsibility for managing the state’s assets, conducting audits of local government, approving state contracts, running the state’s accounting system. The comptroller is also the sole trustee in charge of the state's $143 billion pension fund -- making this public official, as some have suggested, in effect the richest person in the world. For this, the comptroller earns $151,500 a year.

The job is so sweeping, with its combination of quite separate responsibilities, that it might make sense to divvy it up into at least two different jobs, says David Birdsell dean of the School of Public Affairs at Baruch College. Most people would think of running the pension fund alone as a full-time job, he said.

In fact, most states do see the comptroller’s job differently than New York does. All states have someone like a comptroller, and in about half the states, that post is called comptroller (although sometimes spelled differently.) In general, the person in the position must determine whether state expenditures are legal and in compliance with the budget. But said Pat O’Connor, manager of the National Association of State Auditors, Comptrollers and Treasurers, New York’s comptroller performs “an unusual number of other functions. I don’t know of any other comptroller that has the authority to audit local entities,” she said. California, for example, has three different agencies sharing the responsibilities given to the comptroller's office in New York.

While the New York comptroller oversees pension funds, most states rely on a board to do that. And many comptrollers, O'Connor said, are appointed by the governor, not elected, although elected comptrollers are more common in big states than small ones.

With so many tasks, every comptroller emphasizes different things. But as sweeping as the office’s responsibilities are, Hevesi expanded them. Following the discovery of staggering financial improprieties in the Rosalyn school system, Hevesi resumed routine audits of all the state’s 832 school districts.

Hevesi also used the office as “a bully pulpit, a kind of forum for an expert outsider’s observations and recommendations on executive and legislative practices with fiscal and economic implications,” said Glenn Pasanen, a professor of political science at Lehman College and writer for Gotham Gazette. In that way the office has been crucial, Pasanen said, in “opening up the too-closed system of governance in Albany.”

Hevesi tended to focus “on certain areas that were tied together by the general theme of good fiscal government,” such as the state’s debt and the public authorities, said Preston Niblack, deputy director of the New York City Independent Budget Office.

THE IDEAL COMPTROLLER

To insure that whoever took on such a range of responsibilities would be qualified to do so, Spitzer, Silver and Senator Majority Leader Joseph Bruno agreed that the legislature would select the next comptroller from a list of finalists approved by an expert panel. That group consisted of three former comptrollers: Republican State Comptroller Ned Regan, Democratic State Comptroller Carl McCall and Democratic New York City Comptroller Harrison Golden.

The governor had wanted “up to five, high-quality, nonpartisan” candidates, Ned Regan has said, adding, “We interpreted that as management experience and financial literacy.”

Goldin agreed: “The candidates we picked had substantial administrative experience and meaningful asset-management experience.”

But others question some of this reasoning. After all, Henry Stern wrote in New York Civic, “What agency or major corporation did Eliot Spitzer run before he was elected attorney general in 1998? Yet he was an excellent AG.”

Other observers see independence and integrity as key. Herbert London, the president of Hudson Institute who himself ran for comptroller in 1994, stressed that integrity was vital for anyone who manages such a huge pension fund. “You want someone you can trust – someone interested in the people of New York, the pensions of New York and the employees of New York,” he said. The best bet, he said, would be to choose someone from the private sector “not contaminated by the usual political process” and who will not be tempted to use the pension fund for their own political advantage.

There is an inherent contradiction in how New York selects its comptroller. “The governor is saying this is a job that requires special skills,” said Gerald Benjamin, a professor at SUNY New Paltz and an expert on state government. “Yet it is a job that is filled by election.” While there have been concerns about conflicts of interest by comptrollers, Benjamin said that, even though many comptrollers have not had extensive financial or management experience, “There never has been an issue that the comptroller is incompetent. They’ve gone out and hired deputies.”

THE CURRENT BATTLE

Under the state constitution, if the comptroller or attorney general resigns, the state legislature, acting as a single unit, selects a replacement. Each member -- state senator or assembly member, Democrat or Republican -- gets a single vote. Given that Democrats are in the majority, Silver, the top Democrat in the legislature, was expected to play the key role in choosing the new comptroller. It was also widely assumed that the new comptroller would be a Democrat – even though many experts, harking back to Arthur Levitt in the Rockefeller administration and Regan during Mario Cuomo’s governorship, believe it makes sense for the watchdog to be from a different party than the governor.

Silver said he would work with the new governor on the issue. And for a while, he did, agreeing to set up the panel of former comptrollers to screen candidates. Eighteen people put themselves up for consideration, including five members of the Assembly, a state senator, local government officials, and a few businesspeople.

It all seemed to be moving along smoothly – and then the panel announced the finalists. They were:

Martha Stark : The only woman who formally applied, Stark is the city’s first African American finance commissioner. Stark, who grew up in Brooklyn, had several positions in the Dinkins administration, worked in the Manhattan borough president’s office and immediately before becoming finance commissioner managed millions of dollars in youth development grants at the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation. As commissioner, she heads up a 2,300-person agency that collects $18 billion a year in tax revenue.

: The only woman who formally applied, Stark is the city’s first African American finance commissioner. Stark, who grew up in Brooklyn, had several positions in the Dinkins administration, worked in the Manhattan borough president’s office and immediately before becoming finance commissioner managed millions of dollars in youth development grants at the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation. As commissioner, she heads up a 2,300-person agency that collects $18 billion a year in tax revenue.

Howard Weitzman: A graduate of New York City public schools, Weitzman was elected Nassau County comptroller in 2001 and re-elected in 2005. In his official biography, he says he has worked with County Executive Tom Suozzi to “bring the country back from the brink of bankruptcy.” Before becoming comptroller, he served as mayor of Great Neck Estates, worked for the accounting firm KPMG, and founded a healthcare financial services firm and mail-service pharmaceutical company.

A graduate of New York City public schools, Weitzman was elected Nassau County comptroller in 2001 and re-elected in 2005. In his official biography, he says he has worked with County Executive Tom Suozzi to “bring the country back from the brink of bankruptcy.” Before becoming comptroller, he served as mayor of Great Neck Estates, worked for the accounting firm KPMG, and founded a healthcare financial services firm and mail-service pharmaceutical company.

William Mulrow: A resident of Bronxville, he ran unsuccessfully for comptroller against Hevesi in 2002. He is an investment banker, currently managing director of Paladin Capital Group. He has also served with a number of government agencies, including the New York City Rent Guidelines Board, the Municipal Assistance Corporation for the City of New York, and the United Nations Development Corporation. While many favor the appointment of someone with such private sector experience, others question his connections to Excelsior Racing, which has been trying to win control of state horseracing revenue. Spitzer has been reported to favor Mulrow, who has been identified as a friend of the governor’s. Mulrow has sought to downplay this, saying he is “a 50-year-old guy who only met Eliot Spitzer a few years ago” and “one of many people who did vote for the governor.”

Little to none of the ensuing furor has focused on the merits of these three people. Instead it revolves around the number of people on the list and, most important, the people who are not on it.

Many observers expected the panel to pick five – not three – finalists. In coming up with the three, the panel rejected all members of the state legislature who applied for the post. This enraged many in the body, particularly those who wanted the job themselves. Some charged Spitzer had lobbied the three men on the panel, though Regan denied it. The legislators also argued that the process was stacked against legislators and that none of the panelists when they became comptroller had the kind of experience they now are saying is essential for the job.

THE ASSEMBLY CANDIDATES

Although five Assembly members originally applied for the post, only three still appear to be in contention. (One, Pete Grannis, has left the Assembly to become Spitzer’s environment commissioner; another, Felix Ortiz of Brooklyn, has been largely ignored in the press accounts). All Democrats, the three are:

Thomas DiNapoli:  DiNapoli first held public office at age 18 as a trustee of the Mineola Board of Education. Since 1986, he has served as a member of the State Assembly from Nassau County. He chairs the Environmental Conservation Committee. There have been reports that DiNapoli is the favorite of Assembly Democrats – and Silver – for comptroller, but he has denied it. “That’s not my conclusion. We’re keeping it an open process,” he told reporters following last week’s Assembly meeting.

DiNapoli first held public office at age 18 as a trustee of the Mineola Board of Education. Since 1986, he has served as a member of the State Assembly from Nassau County. He chairs the Environmental Conservation Committee. There have been reports that DiNapoli is the favorite of Assembly Democrats – and Silver – for comptroller, but he has denied it. “That’s not my conclusion. We’re keeping it an open process,” he told reporters following last week’s Assembly meeting.

Joseph Morelle:  A resident of Irondequoit near Rochester, Morrell was first elected to the State Assembly in 1990. On his official biography, he says he has been particularly interested in economic development issues. Following the panel’s announcement of the three candidates, Morelle, who resigned as chairman of the Monroe County Democratic Committee to seek the statewide office, issued a statement saying he still considered himself to be in the running. If the panel, he said, “made a decision to exclude candidates solely on the basis â€of their status as state legislators … then it taints the entire process and the transparency and even-handedness that was meant to define it. As long as that question remains unanswered, I remain a candidate for state comptroller.”

A resident of Irondequoit near Rochester, Morrell was first elected to the State Assembly in 1990. On his official biography, he says he has been particularly interested in economic development issues. Following the panel’s announcement of the three candidates, Morelle, who resigned as chairman of the Monroe County Democratic Committee to seek the statewide office, issued a statement saying he still considered himself to be in the running. If the panel, he said, “made a decision to exclude candidates solely on the basis â€of their status as state legislators … then it taints the entire process and the transparency and even-handedness that was meant to define it. As long as that question remains unanswered, I remain a candidate for state comptroller.”

Richard Brodsky:  A member of the State Assembly from Westchester for 24 years, Brodsky ran for state attorney general last year but dropped out because of illness in his family. As chairman of the Standing Committee on Corporations, Authorities, and Commissions, he has emerged as an outspoken critic of the state’s public authorities. Sometimes considered abrasive, Brodsky told the screening panel that that should not disqualify him from being comptroller. “"I am not unaware that it's been said that I have brought a certain roughness and directness to the (political) process," Brodsky said, but, he continued, that “speaks to a fierce allegiance to the public interest.”

A member of the State Assembly from Westchester for 24 years, Brodsky ran for state attorney general last year but dropped out because of illness in his family. As chairman of the Standing Committee on Corporations, Authorities, and Commissions, he has emerged as an outspoken critic of the state’s public authorities. Sometimes considered abrasive, Brodsky told the screening panel that that should not disqualify him from being comptroller. “"I am not unaware that it's been said that I have brought a certain roughness and directness to the (political) process," Brodsky said, but, he continued, that “speaks to a fierce allegiance to the public interest.”

Even before the panelists announced the three finalists, reports began circulating that Silver might want to select someone not on the list. On January 30, Democratic members of the Assembly met for more than six hours to mull their next move: selecting one of the three, uniting behind another candidate, or dividing. If they unite behind a single candidate, he or she would almost certainly get the job; if they fragment, Democrats in the Senate and Republicans in either house could have a role. The Assembly members did not reach a decision and so, for now, the situation remains unclear.

Many believe Silver has few good options. Even if he defied Spitzer and selected a member of the Assembly for comptroller, the governor, who is far more popular than members of the legislature, might come out ahead. He would be portrayed as having tried to challenge Albany cronyism and so he himself would “view this as losing the battle but winning the war,” an anonymous source told the New York Sun. By consenting to the screening panel “Silver agreed to the circumstances where there was the risk of this happening,” said Benjamin. “I don’t see Silver’s way out. The fundamental political point is Silver made a mistake.”

And Spitzer shows no signs of backing down. “There is a list sent up to the legislature. I fully expect that they will choose from among the members on that list. That’s it,” the governor said.

A 'HIGHLY UNDEMOCRATIC’ PROCESS

Such controversy over filling a vacant position is not unprecedented. While no public official has been removed from office in New York State since Governor William Sulzer in 1913, many have stepped down. In 1993, for example, then Comptroller Edward Regan resigned to take a position at Bard College. The state legislature selected H. Carl McCall, a former state senator and a vice president at Citibank, to replace him. McCall went on to win election to the post in 1994 and 1998. A year later, another statewide elected official, Attorney General Robert Abrams resigned, and the legislature chose one of its own, Assemblymember Oliver Koppell (now a member of the New York City Council), to fill out that term. Koppell, though, lost his bid to be elected to the post.

While the legislature chose Koppell “with less fanfare and controversy than usually accompanies the selection of a new village dog catcher,” according to Newsday, McCall’s selection proved controversial. A number of candidates vied for the job. Governor Mario Cuomo threw his support behind McCall. When the Democratic legislature formally adopted that decision, thereby making McCall the first African-American to hold statewide office, Republicans boycotted the election meeting and went to court to block McCall’s selection.

In 1993, the Times termed the whole process “highly undemocratic. No election, no public participation, just a predetermined vote by a heavily politicked legislature.”

The role played by Cuomo and the legislature was particularly troublesome, the paper said. The outgoing comptroller, Ned Regan, the Times wrote “was at his most impressive when he pushed the governor and legislature to reform sloppy and wasteful borrowing practices. Would he have done so if he owed his job to the people he challenged? Not likely.”

What is unusual in the current situation is how long the appointed comptroller, whoever it might be, will serve. Because Hevesi resigned after being re-elected but before serving a single day of his new term, the new comptroller will likely occupy the office for almost a full four-year term without the approval of the state’s voters. Under the state constitution, the next election cannot be held until the next gubernatorial election in 2010.

In contrast, a special election is being held on Long Island this week Tuesday to fill a vacant State Senate seat. Imagine the uproar if the State Senate got to make the choice, instead of the voters, wrote Yancey Roy of Gannett News Service. But voters have no role in selecting the far more powerful comptroller – unless there is a change in the state constitution. And that, wrote Roy, is “not going to happen.”

Â

Do-It-Yourself Regulation: Stated Meeting 2/1/2007

Councilmember Jimmy Vacca sees something threatening his corner of the Bronx. Houses are torn down and bigger ones go up in their places. Calm neighborhoods turn noisy. Cars clog once quiet streets. The city's zoning laws are supposed to protect Throg's Neck against such overdevelopment, says Vacca, but City Hall has made it quite easy to get around them.

In the name of cutting red tape, city law currently allows architects and engineers to decide whether their own projects are in compliance with zoning regulations in many cases – a practice known as self-certification. This practice is based on the reasoning that professionals can be trusted to comply with the law themselves, and that allowing them to sign off on their own projects increases the efficiency of development – much needed in a city that is building itself up at the pace that New York is today.

But many members of the council complain that this privilege is regularly abused, and that violators are not punished. Vacca – who calls the zoning book his "bible", and who has been referred to as both the "de facto Inspector General of the Buildings Department" and the " sheriff of zoning" – is one of the most aggressive critics of such permissive policies. He refers to the self-certification as "the bane of the existence of those who are concerned about overdevelopment." People who have either misread regulations or intentionally ignore them regularly build projects that are larger than zoning laws allow for, or don't include required parking, he argues.

At its stated meeting on February 1st, the council voted on two bills introduced by Vacca. As the law is written now, even those architects and engineers who have been sanctioned for violations in the past are taken at their word when they say their projects comply with zoning regulations. The first (Intro 308-a) would prohibit those who are on probation by the state for previous violations from self-certifying projects.

The second bill (Intro 309-a) lays out punishments for those who falsely claim their projects are in compliance with zoning regulations, and requires the city to notify the state about violators, so that their past transgressions can be counted against them when they apply for renewals of state licenses.

The bills call for increased enforcement, but Council Speaker Christine Quinn said the cost, if any, would be "extraordinarily minimal," noting that the Department of Buildings' enforcement budget was increased last year. The department, which has a budget of about $90 million, reviews over 65,000 construction plans annually.

Both bills passed by votes of 47 – 0. They must be signed by the mayor to become law.

The legislation is the latest in a series of proposals coming from a council task force examining the Department of Buildings. In November, the council passed several bills addressing illegal demolition. Members of the council also introduced three new bills regarding development and construction at last week's meeting.

One of those bills (Intro 521) called for the complete elimination of the self-certification process. Several council members called for such action on the floor as they voted for the bills at hand.

Self-certification started in the 1990s as a money saving move, essentially outsourcing the job of regulation of architects and engineers from a financially strained Department to the industry itself, said Councilmember James Oddo, who led the council task force. City officials should go back to doing this job themselves, he argued. In order to do so, Oddo believes that the Department of Buildings' budget should be increased. In the meantime, he suggested banning self-certification in places where zoning changes had been made recently.

But the Bloomberg administration and Council Speaker Christine Quinn oppose the complete elimination of self-certification, saying that it will stymie development.

"I think that right now we're putting the right level of structure and punishment into the process to weed out the bad operators but allow the good operators the appropriate amount of flexibility," said Quinn. "We don't want to slow down needed and appropriate development."

LANDMARKING BUILDINGS

The council also voted unanimously to re-landmark several buildings on the Upper East Side in the block-long development City and Suburban Homes. The buildings were built at the turn of the 20th century, as an experiment to create a quality alternative to the squalid tenements of the Lower East Side. The Board of Estimate revoked their landmark status in 1990 as a result of lobbying by current MTA Chairman Peter Kalikow, who owned the buildings at the time. The move was part of a flurry of controversial late night decisions made by the board as it closed down – a time that several council members referred to last week as its "going out of business sale."

"You don't get too many opportunities in government for do-overs, and that's what this is: a rare opportunity to right a wrong," said Jessica Lappin, chair of the subcommittee on landmarks. The buildings are in her district, and she led the council's push to have them landmarked again.

The council also voted to landmark the New York Cab Company Stables on the Upper West Side.

A HARLEM HERO HITS IT BIG

Before the meeting started, the council held the latest in the series of government ceremonies honoring Wesley Autrey, the man who jumped onto the subway tracks in Harlem and to save a stranger from an oncoming train. In the last several weeks, Autrey has been the guest of honor at Mayor Michael Bloomberg's State of the City address and President George Bush's nationally televised State of the Union speech. After the national television exposure, doesn't the presentation of a plague in front of a few dozen people seem anticlimactic? Councilmember Peter Vallone didn't think so.

"He has finally, finally hit the big time," Vallone said.

Â

The New Governor's Mystery Agenda

The new governor is a mystery when it comes to housing. No one is sure what he will do about the housing issues in New York City.

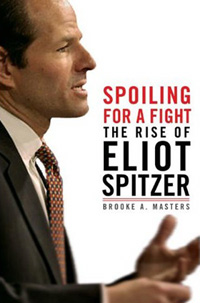

In his inaugural address, Governor Eliot Spitzer was brief in his remarks on housing.

“In New York, we face the twin challenges of high home prices downstate and deteriorating housing stock upstate,” Spitzer said. He then pledged to do an inventory of public land that could be used for new housing development, look for partnerships to build employer-assisted housing and reward communities that reform their zoning laws to encourage affordable housing construction.

What few decisions Spitzer has made in recent weeks seem to have swung both ways: He upset some housing advocates when he let a big landlord off the hook with a slap on the wrist in one of his last acts as Attorney General. But many advocates were encouraged by one of his first acts as governor: He nixed the implementation of new rules, which many saw as pro-landlord, proposed during the tenure of Spitzer’s predecessor George Pataki by the state’s Division of Housing and Community Renewal.

“Pataki tried to undermine the rent laws even further than he already has,” explained Brad Lander of the Pratt Institute for Community Development. “Some of us on [Spitzer’s housing] transition committee urged the Spitzer administration to find a way to undo those things….

“You couldn’t have had a better first day. That was of enormous significance to tenants in New York City.”

Among other things, the new rules would have allowed landlords to charge two months rent as security deposit and made the removal of lead paint a cost that landlords could pass along to tenants in rent increases.

Nevertheless, Spitzer’s housing agenda is still murky. And housing advocates are hardly the only people perplexed at his goals.

“He only put out one press release about housing as far as I know” during his campaign, said Frank Ricci of the Rent Stabilization Association, the group that lobbies on behalf of thousands of property owners in New York City. “I think it’s wait and see.”

Spitzer’s agenda will become clearer in coming weeks with some important decisions:

- He will appoint a new housing commissioner and that person will set the tone at the state’s housing agency

- He will craft a budget with the Legislature and it will reflect priorities.

- He will be lobbied to save the New York City Housing Authority, which is sinking into a fiscal crisis.

What Is On His Mind?

Spitzer did talk about housing during his campaign, even if his ideas on housing were not detailed in press releases. But what did he really say? Housing advocates heard him express lukewarm support for an administrative tribunal, or repair board, to deal with repair issues. They also heard him express some interest in raising the $2,000 rent level at which a landlord can apply to deregulate an apartment upon becoming vacant.

But Ricci said the new governor chose his words carefully. On the repair board, he said, Spitzer said “if local governments pass something like that he would look at it. I think they’re very careful about the words they use and you have to respect that.”

And on rent regulation, Spitzer said he would not change them until they come up for renewal in 2011. “And he has to win an election” before that happens, Ricci pointed out.

In an email, a spokesperson for the governor said the new administration was too immersed in developing a budget to respond to questions about his views on housing issues.

A new commissioner

Housing advocates hold a pretty dim view of the state’s housing agency, the Division of Housing and Community Renewal. Perhaps unsurprisingly, landlords are not so displeased with the agency, which, among other things, enforces the rules that govern rent regulated apartments. In New York City , rent regulated apartments make up almost half of all rentals.

“At least it works now – you get a decision,” Ricci said. “And that’s important…. I don’t know what his philosophy is on (DHCR). I would hope that he would recognize that under [former Governor Mario] Cuomo we had an 80,000-case backlog and that didn’t help tenants or landlords.”

Once Spitzer names a commissioner, the agency’s approach will come more clearly into focus: Will it seek to curtail abuses of the rent laws? Or will it seek to enact new rules for rent regulated apartments that, advocates say, will create new opportunities for landlords to get people out of their homes?

The commissioner will have some influence on the whole future of rent regulated apartments, which are disappearing at a fast rate thanks to the vacancy decontrol provisions enacted in 1997. If Spitzer does indeed wait until 2011 to review the laws – the next time the laws come up for renewal – the debate could be moot, advocates have said: There simply will not be many rent regulated apartments left.

Currently, when the rent on a rent stabilized apartment reaches $2,000, the landlord can seek to deregulate the apartment if it becomes vacant or if the household income is higher than $175,000 for two consecutive years.

“My understanding is that he is not eager to broadly open the rent laws before 2011 but this notion of indexing the rents is something he would consider now,” Lander said. The governor’s administration “doesn’t consider that to be a reopening of the rent laws.”

A Budget

The first budget Spitzer drafts – which he will deliver to legislators on January 31 – will also be revealing. A report by Lander’s office, the Pratt Center for Community Development, urged the new governor to do something about the housing affordability crisis that is affecting communities across the state. In 1998, the report said, the fair market rent for a two-bedroom apartment in the state was $818, but by 2006 it had risen to $1,026 a month. Incomes did not keep pace.

Homelessness in New York City is at record levels while upstate landlords are abandoning properties, the report added.

Lander said he would not expect too much from Spitzer’s first budget.

“Everyone knows the first year’s budget has a lot of constraints,” he said. “The mayor’s housing plan did not emerge in his first budget. What I am hoping is we can see something that is a down payment.”

Lander hopes Spitzer will increase the funds available to finance affordable housing and “look hard” at the reserves that the state’s Housing Finance Administration and mortgage agency, Sonny Mae, have on hand. These funds could also be used to finance the construction of affordable housing, he said.

Some are also hoping the new governor helps the city address problems with its two-year-old rent subsidy program, Housing StabilityPlus. The city has been using the subsidy to help families in city shelters who have public assistance cases find permanent housing. Advocates have raised many questions about the program and a recent expose by the Daily News led State Senator Bill Perkins, a former City Councilmember, to propose legislation to cut state funding for the subsidy because of lead paint violations in some of the apartments.

Instead of cutting the subsidy, however, Spitzer could help the city by eliminating “step-downs” – drops in the subsidy payment of 20 percent per year until it expires in the fifth year. City officials have said it has urged state officials to make the change and some advocates are hoping City Hall makes the subsidy open to low-income working families who are not on public assistance.

Housing Authority Fiscal Meltdown

Spitzer’s first budget could also come to the rescue of the city’s public housing authority, the largest in the nation. Spitzer could restore state funding for the authority, which his predecessor cut in 1998.

The New York City Housing Authority is home to over 400,000 New Yorkers but has seen its budget slashed by the federal government. Last year, the city came to the authority’s rescue, contributing $120 million to cover its deficit. But this year things are even worse: the federal contribution is set to fall by another 30 percent. The authority’s deficit will be close to $150 million again.

In October, the New York City Housing Authority came up with a plan to cover the deficit, but it has outraged advocates: the agency proposed using 8,400 Section 8 vouchers to pay rents in 21 of its developments that were built with city and state money. Using vouchers to do that would effectively reduce the pool of vouchers available to low-income families that have been waiting over a decade for the federal rent subsidy.

City Council Member Rosie Mendez sharply questioned the agency’s general manager about the plan at a recent public hearing, which was overflowing with angry tenants and advocates. But she emphasized that the answer to the housing authority’s problem lie outside of the room.

“We’ve been lobbying as legislators” for the state to restore its operating subsidy, she said during a break. “We’re hopeful that finally the state will step up.”

Joe Lamport is the assistant director of the City-Wide Task Force on Housing Court, a coalition of community housing organizations. Â

Voting Machine -- The Four Finalists

More than four years after Congress passed the Help America Vote Act, there are four voting machines competing for the honor of being New York City's exclusive new voting system.

Over the last few weeks, the manufacturers have been demonstrating these machines to the public throughout the five boroughs; New Yorkers were afforded the opportunity to test the machines and provide feedback at two public hearings conducted by the New York City Board of Elections.

All four machines have voter-verified paper audit trails. They are either optical scan machines, much like the fill-in-the-bubble scantron system used to administer standardized exams, or direct recording electronic machines (DREs), more closely resembling ATM cash machines.

One of the following machines will replace the city's treasured lever machines, called Shoup 3.2, which have been in use since 1962. When this will happen, however, is unclear. While most other states scrambled to meet the 2006 deadline for new machine implementation, New York State did not leave the counties, or the vendors, with enough time to do so. New York City is now in the unenviable position of having to prepare for the nightmare scenario of unveiling new machines in 2008 -- in the midst of an open election for president.

Diebold Optical Scan with Ballot Marking Device

Diebold Optical Scan with Ballot Marking Device

Year Company Founded: 1859

States with counties that use their systems: Georgia , Maryland , Alaska , Arizona , Ohio.

Company Website: www.dieboldes.com

The Diebold Optical Scan machine scans and counts voter-marked paper ballots that are filled out by voters in a private booth at the poll site. Voters are notified when their ballot contains "overvotes" (when more than the allowed selections have been made in an individual race) or "undervotes" (when a voter has not marked a choice of all their selections in an individual race.) Undervotes and overvotes are often collectively referred to as residual votes. The voter can choose to eject their ballot and correct any residual votes found on the ballot or submit it as is.

The system includes a ballot marking device for voters who are not able, or choose not, to fill out their paper ballot by hand. The ballot marker, through one of several technological advances, allow disabled voters to record their vote in private.

ES&S Model 100 Precinct Ballot Counter (Optical Scanner) with Ballot Marking Device

ES&S Model 100 Precinct Ballot Counter (Optical Scanner) with Ballot Marking Device

Year Company Founded: 1969

States with counties that use their systems: Illinois , North Dakota , South Dakota , Oklahoma , Rhode Island , Nebraska , Alabama , North Carolina , and New Mexico , California , Florida , Texas , Hawaii

Company Website: www.essvote.com

The ES&S model functions much like other optical scanners allowing voters to fill out a paper ballot and feed through a scanner to be tabulated. The ES&S model features an LCD display that notifies the voter if an overvote or undervote has been made on the ballot. In the case of an overvote the voter is able to submit the ballot as is, thereby voiding their vote for that race, or eject the ballot and receive a second ballot to make their selections again.

The ES&S machine turned out to better communicate residual votes to voters by displaying the number of undervotes that appeared on the ballot. After scanning his or her ballot, if the machine found undervotes, the voter is prompted to either eject the ballot to make corrections or continue on leaving the undervote as is. In addition, the machines can be programmed to go through each of the undervotes on the ballot, allowing the voter to eject it or continue on. This feature allows voters to select to undervote on a specific race without unintentionally undervoting on other races that may follow.

Sequoia's AVC Advantage Plus Full Face DRE

Year Company Founded: More than 100 years ago

States with counties that use their systems: Florida, Washington , California and Colorado

Company Website: http://www.sequoiavote.com/index.php

Sequoia's DRE model for New York City features a four panel touch screen voting machine. Voters make their selections, which are identified by a check mark, and can review their ballot on a paper receipt before it is cast. The voter is notified of any undervotes they may have made as they are taken to a display with all of their selections for review; undervoted races are highlighted in red. At that time the voter can go back to the ballot and make corrections. Like the lever system, voters cannot overvote in a race, as they have to deselect their choice in order to make a new one.

One of Sequoia's strongest features is the way the VVPT is marked to distinguish cast ballots from invalid ballots. The Sequoia DRE marks spoiled ballots by printing VOIDED at the top of the receipt after a voter chooses to make corrections to their selections. To decrease the likelihood of human error in the event of a hand paper recount, differentiating voided and valid votes with a quick and easy identifier not only makes hand counting more accurate but helps voters feel more confident that there vote is represented accurately.

Avante Vote-TrakkerTM EVC308-FF DRE

Year Founded: unknown

States with counties that use their systems: California ,

Company Website: www.avantetech.com

Avante's full face DRE displays the ballot on a single touch screen panel. Voter's choices are highlighted in yellow, and before casting their ballot voters can review their choices on a paper receipt. Undervotes are highlighted in pink before the voter casts their ballot, allowing for corrections to be made. As the voter makes all of their possible choices in undervoted races, the windows are automatically un-highlighted, letting the voter keep track of their undervotes. The system eliminates overvotes by automatically updating voters' choices. If a voter already selected a candidate for governor and makes a correction, the new selection is highlighted yellow and the old selection is un-highlighted.

Unlike the Sequoia model, the Vote-Trakker identifies invalid ballots with ballots cast by using distinctive numerical codes. The Avante system of separates ballots using replacement (1) or replacement (2) with (1) or (2) at the end of the voters numerically coded ballot rather than firmly noting a valid vote. During a hand recount it seems these receipts would be more susceptible to human error, even if using the program within the machine that identifies valid and invalid ballots.

Doug Israel is policy director, and Andrea Senteno program associate, at Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham Gazette. Â

Mayoral Agenda 2007

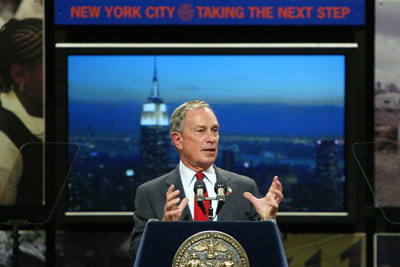

Mayor Michael Bloomberg said he would do lots of things in his State of the City address last week.

There were the little things, promises to:

• retool 911 so it can accept photos of crime scenes from cell phones;

• increase funding for a program that sends nurses to consult first time mothers;

• expand the Civilian Complaint Review Board;

• fill out forms for low-income New Yorkers so they can claim federal tax credits;

• lead a pack of gun weary American mayors as they descend on Washington to demand changes in federal law.

And then there were the big things:

• a $1 billion tax relief plan focused primarily on property tax cuts;

• further changes to the structure of the education system.

Public officials march out such promises every January in their State of the (nation, state, city, or borough) speeches. Governor Eliot Spitzer gave his State of the State address earlier this month; President George Bush will give his State of the Union on Tuesday; and Council Speaker Christine Quinn will give her own State of the City soon.

Mayor Bloomberg started his speech this year by apologizing for one promise he didn't follow through on – there was no Subway Series in 2006. But many of the other things he mentioned last year were either breezed over or not mentioned at all. The city did not pick an architect to design a plan for Governors Island or a developer to revamp Willets Point, and didn't break ground on Atlantic Yards. Despite Bloomberg's promise, the Reptile Wing of the Staten Island Zoo has still not reopened.

Other areas that Bloomberg has made a big deal about got scant mention. Arguably the biggest initiative to come out of last year's speech was the city's anti-poverty efforts, yet the mayor barely touched on the year-long campaign that followed. Nor did he spend more than a few words on his plan to create long-term sustainability policies.

This week we take a look at the two areas the mayor did focus on:

TAX CUTS: The mayor says his property tax relief plan will benefit individual New Yorkers and spark the economy, but economists say it will hardly be noticed.

EDUCATION: After four years, Bloomberg is reorganizing the schools again, but do the changes address the problems that still persist in the city’s public schools? Â

New Bills -- Bike Safety, Public Housing, Subsidized Transportation

At each of the City Council's stated meetings, council members introduce bills, most of which will never become laws (for the process by which bills become laws, click here). As a regular feature, Gotham Gazette discusses some of the legislation proposed at each meeting.

Members of the City Council proposed the creation of a bicycle task force, and asked for increased funding public housing units and transportation benefits for employees at their stated meetings on January 3 and 9.

Bicycle Task Force

Council Member Alan J. Gerson proposed Introduction 498 to create a bicycle safety task force for New York City at its January 3 meeting. Arguing that bicycle use improves personal health and reduces traffic congestion, Gerson hopes the task force will help reduce bicycle related accidents.

Two hundred twenty-five bicyclists died in crashes between 1996 and 2005, according to a report issued by several city agenceis. The report also found 97 percent of bicyclists who died were not wearing a helmet.

By establishing a group to review bicycle routes, patterns and safety the Council will better understand how to improve New York City’s bicycle program. This would be done by changing several bicycle regulations, funding educational campaigns to promote bicycle safety, and improving infrastructure for bicycle lanes and parking. Once established, the task force would develop recommendations on how the city could accommodate bikers safely and practically.

"The idea is to build off the mayor’s initiative on the five borough bicycle paths and get the right people together with the right background and expertise to make important decisions on bicycle safety in the city,” Gerson said. “We’re a busy, crowded city and if we want to make room for bikes we need to do it methodically and scientifically to fully analyze our options.”

Funding Public Housing

New York State built 12,500 apartments in 15 public housing developments throughout the city between 1958 and 1974. While these developments were originally financed with state funds, Albany has not contributed money for operating expenses since 1998. New York City Housing Authority, a city agency, manages the units.

According to Dilan, it costs about $62 million a year to operate the 15 developments. In fiscal 2007, city officials put $120 million in the budget for the long-term viability of the city's public housing. But If the management does not receive any financial assistance, argues Dilan, moderate-income families may see rent hikes, and all tenants may have to deal with reduction in services.

In Resolution 682 Dilan and Mendez are asking state officials to help avoid this, by asking the state to New York State to renew its financial support for the developments.

Transportation Benefits

Encouraging the use of mass transportation is essential in reducing traffic congestion and pollution in the city, according to Council Member John C. Liu. With this in mind, Lui is calling upon the United States Congress to increase public transportation benefits for commuting employees.

The current law allows commuting employees to use up to $105 per month for public transportation, tax-free. Lui wants to increase the monthly cap to $205 with Resolution 683.

This resolution would encourage the use of mass transportation while reducing commuting expenses, especially for the people who ride the Long Island Rail Road and Metro-North Railroad because their monthly commutes may cost more than the $105 they are currently allowed.

Â

Council's First Meetings of 2007: Environmental Issues and City-Owned Buildings

Every two weeks the New York City Council holds its "Stated Meeting" to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Gotham Gazette covers these meetings.

BUILDING HIGH SCHOOLS IN THE BRONX

A controversial $230 million plan to build four schools on a toxic site in the Bronx will go ahead with added attention and public input regarding safety concerns, after a unanimous vote by the City Council at its Stated Meeting on January 9. The council delayed a vote on the project a month ago due to opposition from several members led by Maria del Carmen Arroyo, who represents the area.

The city's School Construction Authority plans to build two high schools, a middle school, and a charter school for 6th to 8th graders on the 6.6 acre site on Concourse Village West, between East 153rd and 156th streets. In all, the schools with accommodate about 2,400 students. The site, a former rail yard, was contaminated by a nearby dry cleaner and manufactured gas plant.

The authority original planned for a $30 million clean up, but an independent environmental consultant hired by community groups said that this might not be sufficient. Several council members from the Bronx said they opposed the plan, and in December the administration withdrew its application pending negotiations over the cleanup.

In an agreement reached late Monday evening, the administration agreed to consider the consultant's recommendations, which will be completed later this month. Administration officials will have the option of declining to implement these measures, but can only do so after explaining them during a public review process. The Bloomberg administration has also agreed to monitor for contamination at two nearby schools, PS 156 and PS 151, and the state Department of Environmental Conservation will clean a nearby site that is contributing to the contamination in the area.

Council members who initially opposed the plan praised the administration for compromising on the issues, and said they were satisfied. The council approved it 45 to 0.

David Palmer of the New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, who worked with the community critics to bring in an outside consultant, said that it would have been better to get the report before approving the project, but was pleased that the public's safety concerns were taken into consideration.

"The public process sets a strong precedent for future school siting proposals on toxic properties," he said. "Given the problem of overcrowding schools, and the lack of available clean land in New York City, the issue is likely to keep coming up."

Indeed, the council said that it would begin work with the administration immediately to change the school siting process to make it more transparent. The current process allows for less community input the city's standard review for land use projects, so that much-needed schools can be fast-tracked. Council Speaker Christine Quinn said that she agrees with this general outline, but that community concerns must be better integrated into process.

"The point is including the neighborhoods where these schools may go as early as possible in the process," she said. " Then if there is a site that there is a lot of opposition to that will be out there early … so we don't end up in a situation like this when we need an extension."

The council also passed a bill (http://webdocs.nyccouncil.info/textfiles/Int%200495-2006.htm?CFID=7007&CFTOKEN=92452565 Intro 495-a) that would set various deadlines for various actions to be taken by city officials, including the mayor's submission of his preliminary budget (February 12), Mayor's Management Report (February 23), and 10-year capital plan (March 28). That bill was passed 45 – 0.

Also, several council members opposed a council vote to http://www.nysun.com/article/46433 sell two townhouses in Boerum Hill for below market value and to give tax breaks to the buyers. The sale was part of an existing agreement between the city and the federal government intended to revamp properties in struggling neighborhoods. David Yassky argued that real estate developers in the trendy Brooklyn neighborhood didn't need the incentives.

The proposal passed, with 39 yes votes, three no votes (Yassky, Alan, Gerson, and James Vacca), and three council members abstaining (Gail Brewer, Bill de Blasio, and Letitia James).

CHARTER MEETING -- ON-SITE POWER GENERATION FOR CITY-OWNED BUILDINGS

The City Council attempted to address concerns that the city's power supply may soon be overwhelmed at its meeting on January 3rd, by passing a bill that would require city officials to consider installing on-site energy generators in city-owned properties to reduce the strain on the power supply in the five boroughs.

New York City has been experiencing record energy demand over the last five years, prompting concerns that insufficient power supply could lead to higher prices, blackouts, and brownouts. A task force on energy estimates that the overall energy supply for New York City will be adequate only until 2012.

New power plants may be necessary, but building them could be technically and politically difficult; new power plants could also be damaging environmentally. Supporters of the bill believe having certain buildings create their own energy could ease stress on the system.

Intro 18-a would require the Department of Citywide Administrative Services to assess whether it could install on-site power generation systems on properties owned by city government that use a certain minimum amount of energy (a peak of 500 kilowatts). These properties include schools, public housing, facilities of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, and office buildings. The council does not have the power to make such a requirement of private property owners.

Such on-site power systems would be required to be cleaner than natural gas power plants, and could use wind or solar power as well as fuel cell technology. The assessment would determine whether such projects are technically possible and economically feasible. It would have to be completed by January 1, 2008, and would be repeated once every five years.

The bill passed by a vote of 47 - 0 - 2. Councilmembers Diane Reyna and Larry Seabrook were absent.

The meeting was the council's annual "charter meeting", which the city charter requires the council hold on the first Wednesday of every calendar year. It functions like a regular stated meeting. The power bill was the only piece of legislation considered.

Â

Hillary, Rudy, And George, But Not Mike ( Or So He Says)

After jumping onto the subway tracks to save a stranger, hero construction worker Wesley Autrey was lavished with gifts and acclaim, including a ceremony at City Hall at which Mayor Michael Bloomberg presented him with a Bronze Medallion – the city's highest honor for civic achievement – and some advice.

Aim for the White House, Bloomberg said; "we need another presidential candidate."

Bloomberg was joking, of course. It has been hard not to hear about the four New Yorkers who are already crowding the field in next year's presidential race (five if you count Al Sharpton, which few people seem ready to do). Senator Hillary Clinton, former mayor Rudolph Giuliani, former governor George Pataki, and Mayor Bloomberg himself are all coyly considering campaigns, though it's not certain how many of them will pull together serious efforts. The Democrats announced last week that they won't hold their 2008 convention in New York City, but you would have to forgive someone for thinking that, as New York magazine put it, "the road to the White House is an extension of Park Avenue."

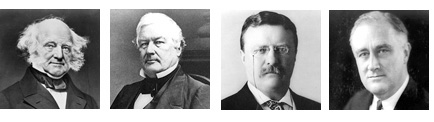

It has been awhile since the days when Franklin Delano Roosevelt was in the White House, eager to hear new ideas about how he could help his fellow New Yorkers. The last New Yorkers to head a major party ticket was Thomas Dewey in 1948. Since his near-miss, no New Yorker has even gotten close. Perhaps the closest was Senator Bobby Kennedy's 1968 campaign – a bid that ended in assassination.

Not coincidental to this dry spell, say many experts, is the persistent anti-urban bent of the federal government over the last several decades, which has drained New York of resources and made being from the Northeast a political liability for political aspirants. When former president Gerald Ford died last month, it brought up memories of the most famous headline in New York newspaper history: FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD. Ford never actually said those words, but in the eyes of many New Yorkers, that hostility has barely faded over the last thirty years.

Not coincidental to this dry spell, say many experts, is the persistent anti-urban bent of the federal government over the last several decades, which has drained New York of resources and made being from the Northeast a political liability for political aspirants. When former president Gerald Ford died last month, it brought up memories of the most famous headline in New York newspaper history: FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD. Ford never actually said those words, but in the eyes of many New Yorkers, that hostility has barely faded over the last thirty years.

Suddenly, though, New Yorkers are banging at the doors of the White House - and, perhaps just as significantly, are in control of some of the most powerful positions in Congress.

Is this simply a coincidence, the confluence of several oversized personalities at the same time and place? Or does it reflect New York's return to prominence in national politics? Either way, what would New York get out of having one of its own in the White House?

THE FOUR HORSEMEN

Among political circles it is considered a bad strategy for a candidate to announce that he is running for president until he has spent several months - or years - campaigning, seeing how it feels and deciding whether he really has a shot. No New Yorker, then, is officially running yet for president in 2008. But at least four are "considering it":

Michael Bloomberg: Democrat-turned-Republican Mayor Michael Bloomberg says he is not running for president, but his name is always included on the list of New York candidates as an independent who will appeal to voters looking for competence over party affiliation. This is partially because the mayor and his senior staff seem to go out of their way to encourage such talk. Bloomberg has said he would make a great president as long ago as 1997, and his close advisors openly discuss him as a viable candidate. Bloomberg himself recently pointed out that he could spend more of his own money in a presidential run than many major party candidates could raise, shortly before he dressed up like Bruce Springsteen at a staff holiday party and sung his own version of "Born to Run." But when asked about his intentions, Bloomberg just smiles and asks what he has to do to convince people that he's not interested.

Hillary Clinton: Polls show Senator Hillary Clinton as the favorite for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination in 2008. She hasn't officially announced her candidacy,  but cynics say it started in 2000, when Clinton moved to New York, switched loyalties from the Cubs to the Yankees, and was elected senator. Since then, she has amassed a huge pool of money, and is enlisting the help of well-respected consultants for her undeclared campaign. Hers is one of the most-recognized names in American politics. One of Clinton's most cited political liabilities is that her reputation as an angry liberal is off-putting to important moderate Republican voters - so she spent $36 million on her 2006 Senate reelection campaign, making sure to win over upstate Republicans.

but cynics say it started in 2000, when Clinton moved to New York, switched loyalties from the Cubs to the Yankees, and was elected senator. Since then, she has amassed a huge pool of money, and is enlisting the help of well-respected consultants for her undeclared campaign. Hers is one of the most-recognized names in American politics. One of Clinton's most cited political liabilities is that her reputation as an angry liberal is off-putting to important moderate Republican voters - so she spent $36 million on her 2006 Senate reelection campaign, making sure to win over upstate Republicans.

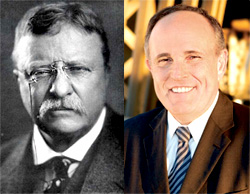

Rudolph Giuliani: After September 11, 2001, former New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani became a national star, his troubled legacy lost among the accolades as a hero and big city crime fighter. He may be hampered in the Republican primary, however, by his New York-like views on abortion, gay rights, and gun control, the public turmoil in his personal life, or his reluctance to abandon a lucrative career in the private sector. Giuliani's own concerns about these political liabilities were dragged through the press recently when private campaign documents were leaked to the Daily News. Giuliani's ability to inspire strong feelings is reflected in one high profile endorsement he has already received for next year's primary: Congressman Charlie Rangel said that he would love for the former mayor to be the Republican candidate so he could attack Giuliani's record as mayor. As a running mate for Giuliani, Rangel suggested his disgraced former police commissioner, Bernard Kerik.

George Pataki: Former Governor George Pataki is not officially running for president just yet; his spokesperson says that he's "weighing the options with his family." But the former governor has quit his job; visited Baghdad and then gone on national television to discuss what he learned; and lavished attention on the states where success in presidential primaries can light a fire under a campaign (he visited Iowa no less than nine times in 2006, and raised money for Republican candidates in New Hampshire). Pataki's efforts have been met with near-universal mockery. Conservatives attack his record on taxes as governor, and his 12-year term in Albany is widely described as a time of gridlock and dysfunction. The best chance most political observers give him is a shot at latching onto a more viable candidate's ticket as the vice presidential candidate.

It is considered very unlikely that all of these candidates will make a serious attempt at the White House. In December, Newsday actually printed the odds that it gave to each candidate lasting until the presidential nominating committees next summer. Clinton was given the best odds (one in three), followed by Giuliani (one in 10), Pataki (one in 50), and Bloomberg (one in 150).

In theory, at least, the 2008 presidential race could come down to a contest between three New Yorkers - a Republican, a Democrat, and an independent. But, to play with Newsday's numbers, the chances of that happening are 0.07 percent at best.

NEW YORK AND THE PRESIDENCY

New York formed a special relationship with the office of the president immediately, when George Washington was sworn in as the first person to hold the office at Federal Hall on Wall Street in 1789. Of course, the first president also advocated burning the city to the ground during the Revolutionary War. The city on the Potomic that took his name, some New Yorkers would argue, has adopted that proposal as the basis for its attitude in dealing with the city on the Hudson in recent decades.

Four presidents were actually born in New York State - Martin Van Buren, Millard Fillmore, Teddy Roosevelt, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt - and at least one more was elected as a New Yorker (Grover Cleveland, who was born in New Jersey, but was raised in Buffalo and eventually became governor). The city was the site of Abraham Lincoln's famous 1860 speech that helped propel him into office, as well as six national conventions. Fourteen presidents have lived in New York City at some point. Two are around today: Bill Clinton, who opened an office in Harlem after leaving office, and Ulysses S. Grant, who is buried on Riverside Drive.

The City's Declining Political Fortunes

Since Franklin Delano Roosevelt died in office in 1945, New Yorkers have been kept out of the White House - and have seen their clout in national politics diminish significantly. In part this is a function of population - both the city and the state make up a relatively smaller proportion of the country's population than they did during the Roosevelt years. Most older cities face the same dilemma. While this does reflect population shifts that began after World War II when the creation of the national highway system led to the birth of the suburbs, there are other causes as well. Politicians see vying for the votes of suburban swing voters as a better use of their energy, knowing that urban areas are full of predictably Democratic voters. There has also been a shift in the prevailing ideology of American politics away from the liberalism associated with New York. Few national politicians want to be tarred as a "Northeastern Liberal."

New York does remain central, however, in the national fundraising scene. New York City-area residents gave more money to national political candidates in 2004 than any other metropolitan area; only the District of Columbia gave more in 2006.

IS NEW YORK BACK?

With New York looking to contribute more than just funding in the 2008 presidential election, politicos and policy wonks are discussing whether the city and the state are regaining central roles in national politics.

With New York looking to contribute more than just funding in the 2008 presidential election, politicos and policy wonks are discussing whether the city and the state are regaining central roles in national politics.

"There's no question that New York has come back from the political wilderness," said political consultant Hank Sheinkopf. He argues that the stereotype that New York is out of step with the rest of the country is inaccurate, but believes that 9/11 - not a realization that New York is not a "bastion of left-wing insanity" - is the driving force behind the city's improving political fortunes.

Presidential hopefuls aside, New York's voice in Washington has recently gotten much louder. Senator Charles Schumer is credited as one of the masterminds of the Democratic takeover in both houses of Congress, making him an incredibly influential member of the newly empowered Democratic Party. With Democratic control over chairmanships of committees - one of the most important markers of congressional clout - New Yorkers have gained immensely. Perhaps most notable is Representative Charles Rangel's rise to the top of the House Ways and Means committee, arguably the most important committee in the house. Other key committee assignments are:

• Nydia Velazquez's new role as head of the house's Small Business Committee;

• Schumer's place on the senate's Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee;

• Senator Clinton's assignment on the Health, Education Labor and Pensions Commitee

• Representatives Gary Ackerman, Gregory Meeks, Joe Crowley, Vito Fosella, Carolyn Maloney and Velazquez's seats on the the Financial Services Committee.

• and Jerrold Nadler and Anthony Weiner's positions on the house Transportation Committee.

If the shift in power from Republicans to Democrats has made New York much more powerful, the factors that have reduced its power have hardly disappeared. New York State is now the country's third most populous behind California and Texas. By the time of the next census, it is expected to fall behind Florida as well. Doug Muzzio, a professor of public affairs at Baruch College, believes that "the sun has set" on the era when big cities drove the country's political agenda.

But what about all those presidential candidates? Muzzio doesn't see them as evidence of any shift.

"I think it has more to do with the particular people rather than some larger contextual change about New York and its place in American politics," he said. "I don't want to sound like a professor, but it's not systemic. It's idiosyncratic."

WHAT'S IN IT FOR US?

New York enjoyed its best relationship with Washington in the 1930s and 1940s, when Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia joked that Roosevelt's White House was "no further than the Bronx." The president acknowledged his soft spot for the mayor and the city. "[LaGuardia] comes to Washington and tells me a sad story. The tears run down my cheeks and tears run down his cheeks and the first thing I know, he Has wangled another fifty million dollars," he is quoted as saying in Thomas Kessner's definitive biography of LaGuardia.

Most political observers acknowledge that the city will not see another era like that, when federal money was used to build the Triborough Bridge, LaGuardia Airport, and the Lincoln Tunnel.

But the federal government's affects New York City on every issue from education to mass transit to health care to housing to immigration.

Bringing a uniquely New York perspective to these issues would almost certainly benefit the city, said Gerald Benjamin, dean of liberal arts and sciences at SUNY New Paltz.

"It would be a convergence of a New York presidency with the placement of New York congressional leaders in key positions that would be critically important," he said. "We've already begun to see that happening."

As New York's representatives grab more influential committee posts, they are eying pet projects and issues that have not gained traction to this point. On her first day as chair of the small business committee, Nydia Velazquez introduced a bill that would encourage bodegas to carry healthier foods in low-income neighborhoods. Jerrold Nadler, who sits on the transportation committee, will likely step up his decades-long pursuit of a freight tunnel under New York Harbor.

The main area where New York seems to be able to swing its political clout immediately is on homeland security funding. Since 9/11, New York officials have complained that this money has been used as political pork, " spread across the country like peanut butter," as Mayor Bloomberg put it in testimony before Congress last week. There have been indications that changes are in the works, though. The Department of Homeland Security announced recently that New York and other major urban areas will get 55 percent of the $747 million pool of homeland security grants, and that New York and New Jersey will get the lion's share of a separate pool of grants for port and rail security.

The main area where New York seems to be able to swing its political clout immediately is on homeland security funding. Since 9/11, New York officials have complained that this money has been used as political pork, " spread across the country like peanut butter," as Mayor Bloomberg put it in testimony before Congress last week. There have been indications that changes are in the works, though. The Department of Homeland Security announced recently that New York and other major urban areas will get 55 percent of the $747 million pool of homeland security grants, and that New York and New Jersey will get the lion's share of a separate pool of grants for port and rail security.

New York's congressmen feel more confident about getting things done in Washington after November's elections. But Congressman Nadler says the delegation's efforts have limits if they don't have an ally in the White House.

"We have more power. We have more influence. But we don't control," he recently told the New York Sun.

While some changes in Washington could be tracked through hard numbers, experts also predict that having a president from New York would inspire a major change in the attitude of the federal government. This would not necessarily be quantifiable, but would be reflected in the overall approach that the federal government took on all domestic issues. "Simply a recognition of the problems that New York City and other urban jurisdictions face, whether it's transportation, infrastructure, schools, etc., any one of those issues would be salient to any of the four" presumed candidates, said Muzzio.

Muzzio and others have pointed out that a Democratic president would be more likely to form a close alliance with the city's overwhelmingly Democratic congressional delegation. But in at least one way it wouldn't matter which party the president came from.

"You won't have a national government run by people who question whether New York is part of the United States," said Benjamin.

Â

Cracking Down on Corruption

The crowd clapped when Governor Eliot Spitzer announced in State of the State Speech last week that he would seek to reform Albany. But cynics could easily note that applause is cheap.

The crowd clapped when Governor Eliot Spitzer announced in State of the State Speech last week that he would seek to reform Albany. But cynics could easily note that applause is cheap.

Sitting behind Spitzer as he spoke was Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno, under federal investigation for misusing state funds. Joining Bruno on the podium was Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver. Together, the two men have set much of the tone in Albany for the last 12 years and preside over a legislature where two members are under criminal indictment, two have had recent run-ins with the law for assault, and numerous others have left under a cloud.

Equally worrisome to many reformers are actions that are perfectly legal. Lax regulations and violations of what laws that do exist have contributed to Albany’s reputation as one of the worst state capitals in the nation.

“You read in every newspaper how many people have been investigated and indicted and convicted,” said Suzanne Novak, deputy director of the Brennan Center for Justice, “There are many factors that go into this,” Novak said but, for starters, the state does not have strict enough laws and does not adequately enforce those laws that it does have.

Eliot Spitzer came to Albany promising to change that. And in his first days in office he began taking concrete steps to do that. But can he really succeed?

A CULTURE OF CORRUPTION

Since the Brennan Center issued a report in 2004 which branded New York’s legislative process the most dysfunctional in the nation, the litany of woes facing state government have become familiar. Three men -- the governor, the speaker and the Senate majority leader -- control the legislative process with individual members often barely knowing what they are voting on. State legislators are allowed to have outside income and even keep it secret – as Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver does – as long as it does not conflict with their public duties. The legislature allocates tens of million of dollars for member items—pet ventures or pork barrel schemes—with little to no public scrutiny.

A redistricting process controlled by the legislature guarantees that lines will be drawn to protect incumbents, giving jobs for life to even the most mediocre Assembly members and state senators. Candidates assured of re-election rake in contributions and use the money for luxury cars and sometimes even legal fees. The state's system of selecting judges has been ruled unconstitutional. New York has more lobbyists per legislator – 20 for each one – than any other state in the county, according to the Center for Public Integrity.

And the rules here appear looser than in many other states. For example, even though he pleaded guilty to a felony, former State Comptroller Alan Hevesi will get to keep most of his state pension. The Albany blog Capitol Confidential contrasted that with Massachusetts, where former House Speaker Thomas Finneran was “almost certain” to lose his $30,000 a year pension after pleading guilty to obstruction of justice charges.

The Albany culture, former State Assembly member Nelson Denis wrote this month, features “a bipartisan Favor Bank built on state contracts, the disposition of state lands, and patronage spending by various public authorities. Every year, Democrats and Republicans posture over their differences, while tacitly collaborating to accommodate the permanent interests of each.”

A MOVE FOR REFORM

In his first days in office, Spitzer tried to take on some of these practices. He issued five executive orders aimed at ethics, stressed government reform in both his inaugural speech and State of the State address. And Attorney General Andrew C Cuomo also sounded the theme

Here is some of what they will do:

Set standards for state workers: In his first day in office, Spitzer issued an executive order barring state employees from accepting gifts designed to influence their decisions, from using state property for personal use, from hiring relatives, and from taking jobs as lobbyists for two years after leaving state government.

Limit the role of politics in state government: Another executive order would bar some state employees from making campaign contributions to the governor and lieutenant governor and would not allow officials to ask prospective employees and contractors about their political affiliations. It also bans elected officials and candidates from appearing in publicly funded ads for state agencies. So, Eliot and Silda Wall Spitzer will not reprise Libby and George Pataki’s roles in “I Love New York” ads.

Regulate campaign finance: In his State of the State speech, Spitzer announced he would submit a package of measures to limit campaign contributions in the state, restrict donations from lobbyists and corporations and begin steps toward instituting public financing of campaigns.

Change the redistricting process: Spitzer said he would submit legislation to establish an independent nonpartisan commission to draw legislative districts in New York. (The next redistricting would follow the 2010 census.) “Until this happens,” he pledged, “I will veto any proposal that reflects partisan gerrymandering.”

Streamline the courts: The governor said he would submit two constitutional amendments aimed at improving New York’s courts – one to consolidate the patchwork of courts in the state’s judicial system and the other to implement a merit process for the selection of judges.

Review member items: Attorney General Andrew Cuomo has said he would go over the 6,000 expenditures on the list to make sure they met the standards for spending public funds.

WILL IT WORK?

Such proposal are “ overwhelmingly matters of common sense that would shake [Albany] to its very foundations,” the Daily News said in an editorial, adding Spitzer’s reform proposals are “ambitious and screwed on straight.”

And many believe they will have an effect. “It’s hard to get things through in Albany, but we now have someone who’s going to push for change,” Novak said. “As attorney general, Eliot Spitzer did not tolerate people not obeying the law.”

But he faces an exceedingly difficult task. Already people were seeing danger signs. Novak notes, that at the same time they applauded Spitzer’s calls for reform, members of the Assembly adopted the same old rules that have long guided their way of doing business. And Senate Republicans again selected Joseph Bruno as their leader – even though he is under federal investigation. Only one GOP senator, John Bonacic of New Paltz, publicly protested the move. "He's been damaged and this ongoing investigation will impair his ability to lead," Bonacic told a local paper. "He should step down as majority leader, even if it's temporarily, until the cloud is removed."