Waterfront Housing For Everyone

In my district in Brooklyn, there are acres of manufacturing land on the Greenpoint-Williamsburg waterfront slated for residential rezoning. Development of this land is expected to yield up to 10,000 houses and apartments in the next few years and dramatically alter the community. While new apartments are desperately needed in the area and the city as a whole, there is also a great need for affordable housing in this lower-income neighborhood.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg has announced an ambitious new housing plan, but because of the state and city budget woes — and federal government indifference — housing subsidies have been greatly reduced. To create enough affordable apartments in places like Greenpoint-Williamsburg, we must find new and innovative policy tools.

One possible solution is to link affordability to the zoning regulations by allowing developers to build slightly bigger if they dedicate some of their profit for the creation of affordable housing. In certain dense areas of Manhattan, a similar special zoning category already exists called, "inclusionary zoning." Developers who build residential apartments in these districts can build a little higher if they include a sizable percentage of the apartments for low-income households. The program has spurred the development of hundreds of low-income homes in the densest areas of Manhattan, but it has not yet been developed for use in less dense districts in the other four boroughs.

Some have argued that the program is not viable outside of Manhattan. However, I believe a modified version of the program could work on rezoned land – particularly those on the city’s attractive and highly developable waterfront. Land zoned for residential development is significantly more valuable than land zoned for manufacturing use, and so landowners on the Brooklyn waterfront will benefit financially with these changes. I believe that asking these developers to contribute some money to low-income housing is reasonable.

Some of the manufacturing land in Greenpoint-Williamsburg has already been developed for housing, though the property has not been rezoned. Developers of this land obtained a "use variance," the rights to build housing where they normally could not, by proving that they couldn’t make money if they complied with existing zoning regulations. Once again, the city is helping developers who will see the value of their property skyrocket. I propose, in the future, requiring these developers to commit to making 20 percent of new residential construction affordable for a typical family in the development neighborhood. Unused manufacturing land represents some of the last stretches of vacant land in the city. Unless the city intervenes, there is no guarantee that any low and moderate income New Yorkers will be able to live in any of the thousands of new apartments developed on these vast tracts. We cannot afford to ignore this opportunity to build affordable housing. The residents of New York City, not just the wealthy ones, deserve a chance to reap the benefits from the development of the Brooklyn waterfront.

New York City Councilmember David Yassky represents district 33 in Brooklyn.

Related Article:

Critiquing The Mayor's Housing Plan by Mark Berkey-Gerard

The Battle Over Rent Regulation

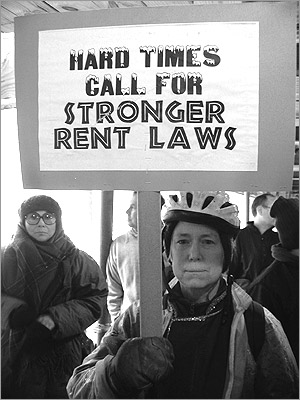

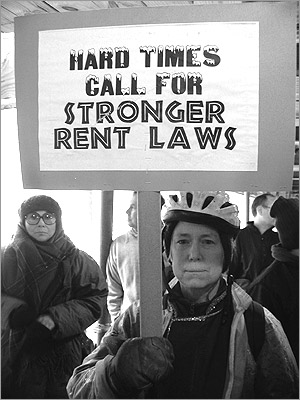

The rally outside Manhattan Housing Court last week started with a chant:

The rally outside Manhattan Housing Court last week started with a chant:

"What do we want?"

"Stronger rent laws!"

"When do we want them?"

"Now!"

It continued with speaker after speaker delivering passionate arguments, dire predictions and fiery exhortations:

"Let's get ready to rumble," one speaker said, while the crowd stamped and cheered in the cold. "We went through this in 1997. We're ready for them again. This is the next civil rights movement."

"I live in a rent-stabilized apartment," the speaker continued.

"I do too!" a few shouted out.

"I've been there for 48 years," the speaker said. "I grew up there. I'm not going anywhere!"

Anybody not well-acquainted with the war over rent regulation might have been surprised to see that most of the speakers being cheered at this rally — most of the speakers, period — were members of the oft-invisible New York State Legislature. (The rent-stabilized resident, for example, was Assemblymember Keith Wright from Harlem.) All those who were present represent New York City, and all of them railed against their upstate colleagues.

For millions of New York City apartment dwellers, the decision that will determine whether they can remain in their homes or be forced out will be made not by landlords across New York City but by legislators 150 miles away in Albany.

With the current law set to expire in June, it is time for the state government to decide whether to renew rent regulation. While the exact size of rent increases in most regulated apartments is determined by the city Rent Guidelines Board, the state government decides whether rent will be controlled at all and, if so, under what circumstances.

WHAT THE LAW DOES

Rent control began in New York in 1943, dictated by the federal government as a means to prevent rampant inflation during World War II. After the war ended and price controls were lifted, the state moved in, allowing municipalities throughout the state to control rents. Today, the state's rent regulations protect 2.5 million tenants living in more than a million apartments in New York City alone. Fifty other municipalities in the state also regulate rents.

Tenants leaders and other advocates see rent control as vital to insuring that New Yorkers, many of whom are life-long renters, do not lose their apartments because of the vagaries of the real estate market. Opponents argue that rent regulation interferes with the housing market, removing incentives for developers and landlords to create more housing. (See related story )

New York provides a variety of protections for tenants of rent-regulated apartments. The laws allow the city to put a cap on how much landlords can raise rents of occupied apartments. Currently, landlords in New York City can hike the rent by 2 percent for one-year leases and 4 percent for two-year leases.

In addition, landlords must renew their tenants' leases when they expire. And tenants have succession rights, meaning that they can pass their apartments on to a relative or a romantic partner. The rent laws also allow tenants to join tenant groups and fight for repairs without being retaliated against by their landlords.

THE LEGISLATIVE BATTLE

The battle over enacting new laws is already underway. Tenant advocates have begun organizing rallies and lobbying state legislators to ensure that when the June 15 deadline comes around, the new rent laws will provide better protections than the existing laws do. Landlord groups have generally urged the elimination of rent control.

In 1997, the last time the law came up for renewal, Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno vowed to end rent regulations. The Democratic controlled Assembly passed its own bill renewing the rent laws well before the expiration date. But the Republican Senate did not move to consider the issue until the deadline neared, giving the Senate the leverage it needed to weaken the Assembly's bill.

By the time the measure passed, it was so weak that tenant advocates claim that one way Albany could guarantee the end of rent controls is simply to simply renew the rent laws as they currently exist.

The state's top two Republicans, Governor George Pataki and Senator Majority Leader Joseph Bruno, have both come out publicly in support of renewing the rent laws "as is."

Such a renewal "would cause a slow death for the rent laws," said Democratic State Senator Liz Krueger of Manhattan who sits on the Senate housing committee.

The Democratic-controlled New York State Assembly got an early jump on the issue when it passed its rent-regulation bill on February 3. The Assembly's bill adds some tenant-friendly provisions to the current regulations and would be in effect until 2008.

Currently, controls on apartments are lifted when an apartment becomes vacant if that apartment can be rented for more than $2,000 a month. The Assembly bill, A.2716a, would end the that.

Tenant advocates see this as crucial. "If this is not repealed," said Dave Powell, an organizer at the city-wide tenant union Metropolitan Council on Housing (Met Council), "It will be the death of rent regulation in New York City." Tenant advocates estimate that almost 100,000 apartments have been removed from rent regulations since 1993 because of this provision.

Powell believes that, with the way rents are increasing in New York City, landlords will one day be able to claim that any apartment could rent for $2,000 a month, which would mean that all apartments would be exempt from regulation.

"If you are a talented businessperson you can absolutely figure out how to get your apartments out of rent regulation," Krueger said.

Landlords are now allowed to increase the rent of a regulated apartment by 20 percent when it becomes vacant and to add on one-fortieth of the cost of any renovations made while the apartment is vacant.

The Assembly bill would reduce the amount that landlords can raise the rent on vacant apartments — the so-called vacancy allowance — to 10 percent of the current monthly rent. It would place under rent stabilization apartments built since 1974 under the Mitchell-Lama program, which provided incentives to developers to build middle-income housing. The current regulations do not include any apartment buildings built after January 1, 1974.

Though the Assembly's bill is more tenant-friendly than the current laws, it does not go far enough for some tenant advocates. Powell faults the measure for not repealing the Urstadt Law, which bars New York City and the other 50 municipalities around the state that have some form of rent regulation from enacting rent laws stricter than those of the state.

"In effect, the law allows the city to weaken the rent laws but not strengthen them," Powell said.

The Assembly's bill now moves on to the Republican-controlled Senate where it is expected to take on a decidedly more pro-landlord look.

"The Republicans controlling the Senate are opposed to rent regulation," said Krueger, who hopes the Senate passes a bill identical to the Assembly bill. "My Republican colleagues from up state do not understand what a housing crisis is like and why we in the city need rent regulations."

A spokesman for Bruno, refusing to talk specifically about what the majority leader plans to do, would only say that the "New York State Senate is dedicated" to providing affordable housing to New Yorkers.

The Senate seems in no hurry to move on the issue . "We have several months before the rent laws expire," said Mark Hansen, a spokesperson for Bruno. "However, the Senate has a much more pressing deadline of April 1, when we need to have a budget passed."

"We are starting ahead of the game this year," Krueger said, noting that in 1997, Bruno was "publicly on record wanting to end rent regulations, but this year he wants to keep them the same." Hansen noted that Pataki also wants to keep the laws as they are now.

The Met Council and other tenant advocacy groups plan to keep the pressure are already organizing to put pressure on and push for stricter regulations. On May 13, "Tenant Lobby Day" in Albany, advocates will hold a rally and lobby legislators. And on June 1 — only two weeks before the regulations are set to expire — tenant advocates will hold a rally at Union Square.

Related Article:

Rent Regulation by Robin Reisig

Rent Regulation

To hear the most adamant landlords and their supporters tell it, rent control has just about destroyed New York

City, denying real estate developers the opportunity to build affordable housing for a reasonable profit.

To hear the most adamant landlords and their supporters tell it, rent control has just about destroyed New York

City, denying real estate developers the opportunity to build affordable housing for a reasonable profit.

Tenants and their advocates believe just the opposite, that rent regulation has saved the city. It has enabled New York to remain a magnet for the young and the gifted and the hopeful, and protected the average New Yorker from the greed of the real estate industry.

The two sides have been making the same arguments for several generations, in a conflict that has seen many battles. Some New Yorkers wonder if one side has already won. How can anyone say that rents are regulated now, when an apartment can triple in rent when it becomes vacant, and a crummy one-bedroom apartment in Manhattan can go for $2,400 a month?

On the other hand, many New Yorkers who live in rent-regulated apartments — and rent regulation still covers slightly more than a million apartments in New York City, or about half of the city's total number of rental apartments — cannot seem to believe that all regulations might actually come to an end.

But that threat is real, tenant advocates say — Republicans in the New York State Legislature tried to abolish it six years ago — and, with the current rent regulations set to expire in June, they have mobilized their forces to preserve and strengthen the laws. (See related story.)

A CITY OF RENTERS

New Yorkers have a uniquely proprietary attitude toward their apartments. Elsewhere in the country, middle class people buy big houses with lawns. New Yorkers hope for a sunny window to rent. Other Americans live in apartments until they settle down and acquire a spouse, a kid, a dog — and a house. Many New Yorkers do their settling in their apartments; some two-thirds of New Yorkers are renters.

At the same time, housing costs are notoriously high here. The average New Yorker currently spends almost 30 percent of income on rent, including gas and electricity. More than a quarter (27 percent) of renters spend half or more of their income on rent, according to a 1999 census housing and vacancy survey.

It is not surprising, then, that rent regulation remains one of the hottest issues in New York, with people on both sides holding fiercely to their positions. Landlords and advocates of a freer market for housing say rent controls reduce tax rolls and discourage new construction.

"With 1.1 million rent-regulated apartments, the city is a showcase for the distorting effects of controls," wrote Peter Salins of the Manhattan Institute. He cited "a minuscule vacancy rate, middle-class families trapped in apartments too small for their needs, wealthy retirees paying a pittance for three bedrooms and virtually no new construction to relieve the strain and to upgrade the housing stock."

Tenants counter that rent control was instituted to protect renters from being exploited. "The rent laws were enacted to eliminate unfair bargaining advantages that landlords have over all consumers who are forced to shop for apartments in an overheated market," wrote Timothy Collins, a former executive director and counsel for the city Rent Guidelines Board. "The law was designed to ensure that a landlord could not charge $1,200 for an apartment that — in a normal market — would rent for only $800."

Collins and other tenant advocates say the drive to loosen rent regulation or to do away with it springs more from the political power of the real estate industry than from the merits of a free market argument.

A LONG HISTORY

While rent regulation may have particular immediacy in crowded, expensive 21st century Manhattan, people have sought to regulate the housing market for centuries. The movement gained momentum in the early 1900s. "Because housing markets, like labor markets, are often anarchic and unstable, the trend throughout the century, learned through bitter experience, has been to subject them to government regulation and intervention in order to try to assure some degree of public peace and justice," Ron Lawson wrote in his book, "The Tenant Movement in New York City, 1904-1984."

Faced with a housing shortage and high rents after World War I, the state legislature enacted laws allowing tenants to legally challenge "unjust, unreasonable and oppressive" rent hikes. These laws stayed on the books until 1928.

In 1943, the federal government's World War II Office of Price Administration largely froze rents in New York City. Tenants organized to preserve the protections after the war, and in 1947 New York established a state rent regulation system controlling rents on all residential buildings constructed before 1947. Today, only about 60,000 apartments remain under that old rent-control law.

In the face of rising rents in 1969, New York City enacted rent stabilization, which extended regulations to buildings with six or more units constructed after 1947. This system today covers at least a million apartments. (One result is a confusion over terminology. Some people refer to "rent control" to mean both the earlier rent control system and the later rent stabilization. Others insist that it is important, and more accurate, to make a distinction between the two, and when talking of both of them together, to say "rent regulation.")

Both rent control and rent stabilization officially exist in response to a housing shortage, and would terminate if the number of vacant apartments in New York City ever rose above five percent of the total housing in the city, which has never happened, according to the official survey.

Concern about housing abandonment, a growing problem at the time, prompted the city to weaken rent regulation in 1971, permitting larger rent hikes. The state legislature also instituted so-called vacancy decontrol, which removed vacant apartments from rent regulation.

Rent regulations for all apartments thus seemed doomed. Tenants and their supporters contended that the changes sent rents skyrocketing and were driving people out of the city. In response, the legislature ended vacancy decontrol in 1974.

Observers differ over how much effect the regulations actually have on rents. Barbara Elstein Katz, a retired analyst with the Department of Housing, Preservation and Development, has calculated on behalf of the New York State Tenants & Neighbors Coalition that the median monthly amount that tenants pay to landlords for rent-regulated apartments in the city is $640, while for unregulated it is $1,090 — 70 percent more.

Landlord advocates say this is not true, that there is less than a $150 difference. According to Dan Margulies, executive director of Community Housing Improvement Program (CHIP), a trade association for apartment building owners, the median unregulated rent in 2002 was around $850.

The discrepancy is because Marguilies includes the small mom-and-pop buildings (buildings with fewer than six apartments) in his calculation, and Katz does not.

CHANGES IN THE SYSTEM

|

CHALLENGING RENT HIKES Under rent regulations, tenants can appeal to the state Division of Housing and Community Development, claiming that their rent is too high. But such a challenge requires detective work. Vivian Dee, head of the Park West Village Tenants' Association in Manhattan Valley, has become an expert. Last year, for example, she helped two tenants who thought they were being overcharged on rents for their separate apartments. Looking over two canceled checks the landlord had provided as evidence of improvements made to the apartments, Dee noticed something odd. "The date of the check was the same. . . . The amount of the check was the same. The number of the check was the same," she recalled. "I was overjoyed." Dee was delighted because the identical $14,550 checks bolstered the tenants' call for a rent reduction. The owners had claimed that the full amount of the check was for only one apartment. A quick look at other checks revealed that this was not the only time the same check had been used as alleged proof of work for more than one apartment. "It was a mistake," said Santo Golino, a lawyer for the landlords, P.W.V. Acquisition. "I think we've fully explained it satisfactorily" for the state. Golino declined to give that explanation. Park West Village, huge high-rise buildings, between West 97th and 100th Streets, near public housing projects, was built with government help as affordable housing. The tenants' association advises new tenants to check to see if their rents are legal. The new Park West Village tenants have won a number of their cases at the state housing division, but the landlords are appealing most of the decisions. Linda Anderson, a college professor and single parent of a 6-year-old son, had been paying more than half of her net salary for her $2,400-a-month apartment at Park West Village. When she looked into her new apartment's rent history, she discovered, "Lo and behold, to my amazement, the rent had been increased" from $935.95 to $2,400. While the landlord claimed $50,000 in work had been done on the apartment, the cabinets do not align, and the paint and plaster are uneven. In the bathroom, tiles are cracked, and paint has dribbled down onto the tiles. She now pays less than $1,200. Anderson said, "I felt like I had really once tested out the system and challenged it and heard that my voice was heard" |

While rent control survives, the state has whittled away at it over the last decade.

Rent controls are "almost like a drug. We all grew up in that kind of environment," said Joseph Strasburg, president of the Rent Stabilization Association, which represents property owners. "We cannot end it overnight."

But tenants see an effort to phase it out. A law passed in 1993 allowed landlords to add one-fortieth of the costs of any improvement they made to a vacant apartment to the rent charged the next tenant. In 1993 the City Council and in 1994 the State Legislature decontrolled rents on vacant apartments renting at $2,000 a month or more if the new occupants' household income was $250,000 for two consecutive years.

In 1997, the New York State Legislature extended the rent stabilization law for another six years — or at least that is what many New Yorkers believed. From the apartment owners' point of view, the 1997 law fixed a flawed system. From the tenant point of view, it created injustices (pdf file) and threatened the very existence of rent regulation. Republicans such as Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno now are willing to let the current law stand — testimony, some observers say, to just how weak that legislation is.

The 1997 law included vacancy decontrol for so-called luxury apartments, costing $2,000 or more a month, regardless of the new tenants' income. Landlords discovered all they need to decontrol the rent on an apartment is for it to become vacant.

Landlords can immediately increase the rent on a vacant apartment by at least 20 percent—more if the departing tenant had lived in the apartment for more than eight years. The landlord can also add to the monthly rent one-fortieth of the cost of any repairs made to the home.

If the rent was $1,000 when the tenant moved out, "the rent immediately goes to $1,200. The landlord gets that without a lick of work," explained Michael McKee, associate director of New York State Tenants & Neighbors Coalition.

Then, McKee continued, "The landlord asks himself, 'How much do I have to spend to get the rent up to $2,000?' The answer in this case would be $32,000, because the landlord can add one-fortieth of the costs of improvements to each month's rent — forever."

So, McKee said, the landlord puts in new floors, wiring and other things, and "the apartment is forever de-regulated."

Landlords don't even need to document that they have actually done the work unless a tenant challenges the rental price.

Landlords say these rent hikes are fair. "I don't think landlords generally are responsible for what somebody will pay if they want to live in a particular area," said Margulies of the Community Housing Improvement Program. "I used to live on Upper West Side, and I couldn't afford it so I moved. This is apparently a foreign notion to most New Yorkers: There is no God-given right to live where you want to live."

Owners and tenants dispute how many apartments have been deregulated to vacancy decontrol. Owners say no more than 50,000 or 55,000 units. Tenants say 99,000.

When a building becomes a co-op, rental units in the building are decontrolled as soon as the current tenant leaves.

"We calculated that at the present rate of deregulation, half the universe will be deregulated in seven to nine years," said McKee. "In 10 to 15 years, if we don't get vacancy decontrol repealed, there will be no rent regulations at all. There will be so few [rent-regulated] tenants [that they] will no longer have the political ability to get the laws renewed for another period of time, which is clearly the real estate strategy."

As tenant advocates see it, the 1997 law has resulted in tens of thousands of high-rent tenants living without right of tenure and without even a right to renew their leases. "Taking steps against the landlord for code violations and repairs could result in the anomalous situation of people moving into high-rent apartments and being afraid" to complain, McKee said.

Suspecting that they might be paying illegal overcharges, hundreds of tenants call Tenants & Neighbors, McKee said, but often tenants in de-regulated apartments are not willing to take action. "People say, 'If I file and lose, he won't renew my lease.'"

The 1997 law also requires that tenants seeking to challenge rents do so within four years of the hike. This four-year statute of limitations is "one of the greatest reforms" of the 1997 law, said Strasburg. Otherwise, he said, new owners could be penalized and forced to pay huge amounts in back rent and damages. "We're not talking about sophisticated owners," he said. "We are talking small property, not deep pockets."

Tenants, however, say the four-year limit can reward landlords who commit deliberate fraud.

Despite the 1997 laws, tenants still have the right to challenge rent hikes—and some succeed.

McKee advises new tenants not to question the status of the apartment before they move in. But immediately after that, the tenant should check the apartment's rent history with the borough office of the state Division of Housing and Community Renewal. If the rent skyrocketed but it looks like extensive renovations have not been done on the apartment, the tenant might have grounds for a rent reduction. Tenant organizations say they often need to hire an engineer to estimate the actual costs of the work and to document that claimed improvements were not made.

THE REVISED CODE

Other state actions have further eroded tenant protections. In December 2000, the state Division of Housing and Community Renewal revised the rent Stabilization Code. Advocates for both tenants and owners agree it helps owners.

One of the most widely publicized provisions could allow owners to evict tenants who charge roommates more than a "proportionate share" — usually half the rent. The code, which has many provisions, also lets landlords increase the rent when a tenant moves out, even if the tenant was there for less than a year. Owners can collect a rent surcharge from tenants who installed their own washing machines, dryers or dishwashers. Owners who want to evict a tenant so they can use his or her apartment for their immediate family can now consider in-laws immediate family.

With these changes, "the executive branch, meaning [Governor George] Pataki, turned the state housing division from an incompetent but fair agency to an incompetent pro-landlord agency," said Sam Himmelstein, a lawyer who represents tenants. "I've seen apartments go overnight from $1500 to $10,000. Who's that helping?"

The answer to that question depends on where you stand in the rent battles of New York.

Related Article:

The Battle Over Rent Regulation by Sam Roseme

Midtown West Side Story: A Conversation With Robert Moses

Â

I had a dream the other night that Robert Moses, the city's famous master builder of the Twentieth Century, came back from the dead to visit New York. Yes, the long-reviled Moses who bulldozed neighborhoods and replaced them with expressways and high rises; who built parks and parkways in the suburbs; who re-shaped New York for the car. (See Robert Caro's The Power Broker on the Land Use book list.)

Moses came back when he saw Mayor Michael Bloomberg's plan for "Midtown West," the area of Manhattan once known as Hells Kitchen.

Midtown West would basically bring an end to Hells Kitchen, the historic rough-and-tumble working class neighborhood on the west side of Manhattan. This is the neighborhood where West Side Story took place, where generations of immigrants lived, where tens of thousands of New Yorkers still make their home. It's a neighborhood that's been depleted of its population over the last century, cut up by giant renewal projects like the Jacob Javits Convention Center, the Port Authority Bus Terminal, Lincoln Center, and the access ramps to the Lincoln Tunnel. Decades ago, the northernmost part of Hells Kitchen was renamed "Clinton" in efforts to distinguish it from its notorious past.

The plan includes a stadium to be built over the west side rail yards that would be a keystone in the 2012 Olympics, should New York City win the world competition for that event. It also involves extension of the number 7 subway line. The city would give developers hefty zoning bonuses to encourage high rise development in two core areas. A "mixed use" district would incorporate some of the remaining low- to mid-rise residential, commercial and industrial uses. New office buildings would be allowed in the adjacent garment district, where there are now strict limits on new construction. Running through Midtown West and lining the Hudson River waterfront would be an open space network. The plan for Midtown West is basically the same as the one put out by the City Planning Department almost two years ago, and design principles released by the department last fall.

WALKING WITH ROBERT MOSES

In my dream, Moses was walking the streets of Hells Kitchen - sorry, Midtown West - with me. I don't know where he went after he died in 1981, but I guess they didn't have limos there. (When he was the planning czar of New York City, Moses wouldn't be caught dead walking anywhere.)

Moses told me he came back because he was so happy that Hells Kitchen was finally going to be wiped off the map, just like all the other neighborhoods he got rid of while he engineered the city's massive urban renewal programs.

"What do you like about the mayor's plan?" I asked him.

"Well, first of all he did it my way," Moses said of the new mayor. "Didn't listen to those people who live there. What do they know anyway? You have to think big and think about the future! You want to expand midtown to the west, just do it! How do you think we got Lincoln Center?"

"But tens of thousands live and work here," I said.

"Look at this neighborhood, it's such a mess you might just as well start all over again. You've got the Port Authority Bus Terminal with all those monster buses, all those ugly parking lots, the access roads to the Lincoln Tunnel, the rail yards, a bunch of small warehouses and industries. And there sits the lonely Javits Convention Center. Who would want to live here or even visit with all this noise and pollution? The mayor's got the right idea. Change its name from Hells Kitchen to Midtown West. Turn it into a high rise business district. Get the people off the ground."

MIXED USE

"But this area between Eighth and Ninth Avenues is supposed to be for mixed use," I said. "What do you think about that, Bob? You were always for the separation of uses."

"That's what happens when everybody reads Jane Jacobs and all that garbage about a fine-grained mixture of uses," Moses replied. [see The Death and Life of Great American Cities on the Land Use book list]. "They start muttering that stuff and pretty soon they believe in it. But if you read the city's plan (and I always do my homework) what they're really doing is converting it to a mid-rise and high-rise residential district by letting people build new apartment buildings. That will jack up rents so that none of the small businesses will stay. So it won't be 'mixed use.' The planners are just being clever, God bless them.

"The same thing with the Special Garment District," Moses continued. "That district, on the east end of Hells Kitchen, was set up to protect the garment industry. The planners know the special district rules are only there to protect those jobs, which aren't really good jobs like those in the finance and banking sectors. So the city's going to allow high rise offices to be built there. That's going to encourage speculation and create political pressure to drop the special district protections. You understand that's not the way I got rid of industry. I would just go in with my urban renewal powers, take the land, knock everything down and start all over again. But these planners don't have the courage it takes. They just follow the big private developers and hide behind the zoning rules. I did everything with strong public authorities."

THE #7 SUBWAY LINE

"Bob, what do you think about the idea of extending the #7 subway line? You were never an advocate of mass transit."

"Well, it's only a little more than a mile. It's not like putting in a new subway line or putting more buses on the streets. If it helps develop the area, I can live with it."

"Bob, instead of spending a couple of billion dollars to build a mile of subway line, why not build a trolley (call it "light rail" if you will) from Times Square at one-tenth the cost?" There are many such proposals. "Then the city could really create a pedestrian-friendly midtown. They would divert traffic from midtown so trolleys could run all day and night from Times Square to the waterfront and Convention Center."

"You Ivory Tower intellectuals are all the same!" Moses exclaimed impatiently. "Trolleys died before I did. You can't interfere with the God-given right of every American to drive wherever they want and whenever they want."

"So you must like the city's plan to shut down all the parking lots in Hells Kitchen - excuse me, West Midtown - so developers can build high rises on them, and build parking garages with even more spaces." I said.

He nodded his head in agreement.

"But that will encourage more traffic in the area, not less," I said.

"Traffic congestion means the city's a success," said Moses. "Besides, the city can always build more highways and widen streets."

It's that kind of thinking that keeps more people from coming to the city, but I didn't want to get him mad. He clearly hadn't lost his faith in the ability to engineer the city out of its problems.

ZONING BONUSES

"Bob, what do you think about the city's idea of giving zoning bonuses to developers? They'll let them build up to 50 percent more than the zoning would allow if the developers give the city money to pay for public infrastructure improvements in the area. Neat idea, huh?"

"Hey, that's a good one," Moses replied. "You know, a trick like that worked in Battery Park City so it could work here too. Proceeds from all that upscale development in Battery Park City were supposed to go into a trust fund that was to finance low- and moderate-income housing. About half the money never got collected and no one knows what happened to the rest of it. Neat idea when you've got a budget deficit. Of course Mayor Bloomberg will have to cut something else to pay for the infrastructure in West Midtown. By then nobody will remember the zoning bonus."

THE STADIUM

"And what do you think about the stadium proposal?"

"This kind of thing still stirs my heart," Moses said. "When you had all that opposition to building a stadium on the west side of Manhattan, the city came up with the Olympics 2012 plan. A stroke of genius. The Olympics plan was really done my way, by the specialists and without all those noisy neighborhood people. So now the loud-mouth nay sayers have to make a case not only against a stadium but the whole Olympics Axis." (See the Olympic 'X'.)

PUBLIC HOUSING

"Bob, you built a lot of public housing," I said. "But there's no mention of low-income housing in the plan for West Midtown."

"I only built public housing because I had to put the people I relocated somewhere," Moses replied, "and besides the federal government paid for it. Today all the feds do is give tax breaks. Happily, most people in Hells Kitchen were already forced to move. West Midtown will have midtown rents, so there won't be any place for poor people. Hells Kitchen will be no more. That's progress!"

OPEN SPACE NETWORK

"Bob, the plan has this open space network running through it, and the waterfront access. What do you think about that?"

"Now this is a bit ridiculous," Moses said. "What they're proposing isn't open space, it's just a bunch of trees on the street and wide sidewalks for the tourists. You wanna see open space go to Jones Beach and the other great parks I built. They put a little walkway on the waterfront and call it a park! Anyway, I guess parks don't belong in the city."

I thanked Robert Moses for the exciting walk and the lesson in city planning. After I woke up I looked around for my copy of Jane Jacobs.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Planners Network Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.

Lots Of New Plans; Any New Visions?

Lately lots of planning has been going on in New York City -- long-range planning, looking far into the future, envisioning what the city will be like in 10 or 20 years. Mayor Michael Bloomberg recently announced a broad plan for Lower Manhattan and a housing plan for the city. The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation recently unveiled nine designs for the World Trade Center site and is getting ready to announce a master plan for the site. We also have an ambitious plan for the 2012 Olympics. And, though most citizens haven't heard about it, the Department of City Planning has a strategic plan. Even the media has the visioning bug. The New York Times asked twelve prominent New Yorkers on January 5 to look into their crystal balls. Civic groups have been leaders when it comes to looking into the future, as witnessed by the array of civic groups that have come forward to discuss rebuilding lower Manhattan after 9/11. Before the last mayoral election, civic groups went into high gear, hoping newly elected officials would heed their plans. Some were quite successful, like the long-range housing plan developed by Housing First!, a coalition of housing and development groups, and the plan for solid waste by the Consumer's Union/Organization of Waterfront Neighborhoods, both of which formed the basis for recent policy initiatives in City Hall.

So these days lots of people are thinking about the future of the city. One of the more surprising turns is that even government is getting in on the act. In fact, there seems to be a shift in City Hall, small but significant, away from the short-term, narrow planning that has characterized government ever since the first fiscal crisis in the 1970s. This is especially notable at a time when the current fiscal crisis is pulling decision makers toward short-term solutions to plug holes in the budget.

Legacy of Fiscal Crisis

Unlike many other cities in New York State, New York City has never approved a broad, comprehensive master plan that could serve as a guide in making policy over a long period of time. It's probably just as well. New York City is too big, diverse and complex for a single plan. Would you want an all-powerful planning agency made up of technocrats in a downtown office drawing up blueprints for your neighborhood? Could they possibly understand the diverse realities and needs in this multi-cultural city with hundreds of diverse neighborhoods? That is why the only planning that makes sense in New York has to be based on the communities and involve the communities. There can still be a city-wide vision and a broad city-wide strategy, but it has to relate closely to the city's diverse communities.

Some argue that New York is already developed, so that much of what government has to do is manage the city, not dream up grandiose plans for the future. The problem with this argument is that even the most stable parts of the city are changing all the time. People's problems and needs change, and if government and neighborhoods can anticipate change they can also create it.

While it's probably impossible to have a single monolithic vision and plan for the future of the city, it does make perfect sense to have many. In fact, the city's charter recognizes this (in Section 197-a) and gives government and neighborhoods, through the community boards, the authority to develop a whole range of possible plans. According to the guidelines set out by the Department of City Planning, a plan can cover an area as small as one city block, a neighborhood of 100,000 people, or several neighborhoods. It can cover economic and social development as well as physical development.

Limited Visions

Despite the signs of progress, there is still a lot of short-term thinking amid the strategic planning. Too much of what passes for planning is akin to the kind of strategic planning done by corporations to mask what is basically short-term, bottom-line thinking.

City agencies do strategic plans, but they are limited to their own goals and priorities. They are developed internally, without citizen participation, and are limited to the functions the agencies serve. Agency plans can change abruptly when the mayor leaves office. Especially since term limits, really visionary, long-range thinking is impractical when the mayor, city council members and other elected officials barely serve long enough to learn how things work.

There are also many questions about the new wave of planning initiatives. Are the plans for lower Manhattan anything more than icing on the cake for big real estate deals? Are the plans for Olympics 2012 any more than a collection of mammoth public works projects aimed at spurring development on a few key sites? Are we witnessing a rebirth of the spirit of Robert Moses, the great master planner of the 20th Century who destroyed communities to build highways and high rises? Where, among all these plans, is the overall strategy for the city? Is it in the minds of the mayor and his aides, where it doesn't get debated in the messy process of formal plan approval where diverse communities can be heard? And amid all the big plans for changing the physical city, where are the strategies and plans to improve the quality of neighborhood environments, education, health care, employment, and affordable housing?

Department of City Planning

A newcomer to the city might wonder how the city's officials envision the future of the city, and they might, logically, go to the Department of City Planning (DCP). The Department of City Planning's Strategic Policy Statement outlines eleven priorities. However, they are the agency's priorities, developed by and for the agency, not necessarily priorities for all of us. Our newcomer might be disappointed that about half of them have to do with making changes in zoning regulations to promote new development – perhaps a worthy cause in some cases but obviously there is a lot more to the life of the city that zoning does not and cannot deal with. Zoning rules govern how land can be used, so they are of primary importance to developers. But zoning is an arcane system of regulations that only a few technocrats understand. It is not a plan, but is too often used as a substitute for a plan.

Our newcomer would also be disappointed that the Department of City Planning does not have many plans. In this city with hundreds of diverse neighborhoods, there are no more than a dozen or so approved community plans, and most of them were done at the initiative of the communities. The planning department's strategic policy statement goes beyond zoning when discussing a regional transportation agenda, public access to the waterfront, and the promotion of excellence in design. In these areas the department has made major advances in the last decade, including a waterfront plan, bicycle master plan, ferry plan, etc. Perhaps the new-found passion for planning that has infected the city will flourish anew in the Department of City Planning?

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Planners Network Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.

Homeowner Troubles

New York City's property tax hike of 18.5 percent, which became law in December 2002, will transfer an additional $837 million from homeowners into the city's budget this year. This is just the latest example of how homeowners, who occupy nearly one million households in New York City, are shouldering unanticipated higher housing costs.

This turn of events mirrors a national trend recently reported by the Center for Housing Policy, the research affiliate of the Washington DC-based National Housing Conference.

"Today, homeowners comprise the majority of working families with critical housing needs," reports the author of America's Working Families and the Housing Landscape - 1997 - 2001 (in pdf format). The study found a 60 percent increase in the number of working families with critical housing needs, defined as either paying more than 50 percent of income for housing costs or living in substandard housing conditions. It defined working families as those earning between $10,712 and 120 percent of their area's median income.

Previous versions of the study had found that renters were more likely than homeowners to have critical housing needs. But in 2001, 53 percent of the families with troubled finances owned their homes.

Brooklyn and the Bronx top the national list of counties whose homeowners are burdened by tough housing cost/income ratios, according to data from the 2000 census, reported in the New York Times. Homeowners in those boroughs have the nation's highest percentages of homeowners paying more than 35 percent of their income on housing, although lenders have traditionally kept mortgage payments to no more than 28 percent of income.

That standard has relaxed in recent years and may be contributing to increases in mortgage defaults.

Default can be a result of unexpected unemployment. "With the economy getting worse over the last few years it seems likely that homeowners are affected and are taking a hit on the income side," said Barbara Lipman, research director for the Center for Housing Policy.

But higher housing costs from property taxes and rising insurance premiums can also put owners in danger of defaulting on mortgages and tax payments, which can begin a cycle of abandonment.

"A number of owners, especially those in low income areas, have voiced a lot of concern about their tax bill, combined with new water bills, along with the cost of insurance and the price of oil which has not gone down in three years," said Frank Ricci, of the Rent Stabilization Association, a landlord group. "We have a lot of people very concerned with how long they will be able to last.

"You don't see the effects right away," he said. "The typical owner may start operating at a deficit six months from now. Most of our small owners work another job and they'll start subsidizing the building, and that can only go on for so long."

In tough times like these, some experts say the smart money should rent. Renters are able to adjust their housing/income ratios more easily by simply moving into an apartment that better suits their needs. And while renters might eventually shoulder the burden of increased property taxes or insurance costs, they can also bid rents lower, as has happened in parts of the city over the past year.

Nationally, homeownership is near its all-time high, at 68 percent, even as housing prices have far outpaced inflation and earnings gains, leading to talk of a housing bubble. Since 1995, the country's home prices have increased by 47 percent while overall inflation has been 17 percent, according to Bankrate.com, a website that aggregates financial data.

Homeownership has increased in New York City too, albeit much more modestly. It went from 30.0 to 31.9 percent from 1996 to 1999, according to the New York City Housing and Vacancy Surveys.

Rebecca Webber is a journalist who has covered housing issues for Gotham Gazette since July 2000.

Vision For 21st Century Lower Manhattan

Remarks by Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg given at the Regent Wall Street Hotel

Good morning.

It´s great to be here at the Regent—host to some of New York´s most important moments during the last year.

This is where we held the reception for the members of Congress after their historic joint session commemorating 9/11.

It´s where President Bush gave a significant speech on corporate responsibility.

And today, it´s where I want to outline a vision—for a New Beginning for Lower Manhattan.

Next week, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation will make public seven proposals for the future of the World Trade Center site—the product of months of work by some of the best design teams in the world.

What you will see, will be very different from the six site plans that were presented last summer. Some of these new designs make eloquent statements about what happened on 9/11; they truly are capable of instructing and inspiring future generations. Some speak of hope -- and renewal -- more powerfully than any words can. Some boldly restore the skyline - in ways that say, in no uncertain terms, this is New York -- and the terrorists didn´t win.

Some do all three.

For this, we must thank the LMDC -- led by John Whitehead and Lou Tomson -- who have worked so closely with Governor Pataki and me…with the Port Authority…and with the many individuals and groups who have a rightful stake in what gets built at the World Trade Center site.

But no matter how magnificent the best design for the 16 acres of the World Trade Center site proves to be, it must be complemented by an equally bold vision for all of Lower Manhattan – a New Beginning for Lower Manhattan – that meets the needs of all of New York City…and of the entire region.

We cannot afford to assume, that what goes on the 16 acres will itself guarantee a bright future for Lower Manhattan.

We´ve done that before.

When the World Trade Center was first built, it was hailed as a cure-all for everything that plagued Downtown. True, it came, over time, to embody the spirit of Lower Manhattan. It was commercially bustling -- and an international icon. That´s why the terrorists destroyed it.

But, if we are honest with ourselves, we will recognize that the impact on our City was not all positive. The Twin Towers´ voracious appetite for tenants --weakened the entire Downtown market. The underground mall, while popular, detracted from the vitality of the streets that surrounded it by siphoning pedestrians away from above-ground stores.

The World Trade Center did not – as its objective was – increase employment below Canal Street. In the 1970s, 22% of all Manhattan jobs were Downtown. By 2000, that had declined to just over 19%. The number of jobs Downtown, during that period, actually declined by 64,000. And similarly -- with tourism -- before 9/11, only 25% of all tourists to New York came Downtown. Today, in the city that never sleeps, much of Lower Manhattan goes to bed promptly at 6 o´clock.

Of course, it wasn´t just the World Trade Center that contributed to this decline. We have underinvested in Lower Manhattan for decades. It´s been seventy years since we built a new transit line Downtown. There is far less open space here than in other places around the City. There aren´t enough schools either.

The time has come -- to put an end to that, to restore Lower Manhattan to its rightful place as a global center of innovation -- and make it a “Downtown for the 21st Century.’

To do so, we have much to build on.

First, there´s tradition.

Lower Manhattan has always been where ideas were first tried… opinions first expressed… news first spread. Our first president was inaugurated here. Our harbor was the port for the first steam-powered ferry. When Thomas Edison first turned on streetlights, he did it in Lower Manhattan. New York´s first subway began directly under City Hall. The original Great White Way was Downtown. At a long-gone buttonwood tree on Wall Street, the first American stock was traded.

From the very beginning, Lower Manhattan was open to anyone who had a dream - and was willing to work. Just 22 years after it was first settled, 18 languages were already spoken here. This mixture of peoples and ideas -- fueled by dreams -- fed the competitive fires that made Lower Manhattan give birth to the greatest city in the world.

It was no accident that the Statue of Liberty was placed off the Battery. And it was no accident that Lower Manhattan has witnessed the construction of the world´s tallest building -- nine times -- culminating in the World Trade Center itself.

Moving forward, Lower Manhattan must become an even more vibrant global hub of culture and commerce, a live-and-work-and-visit community for the world. It is our future. It is the world´s second home.

On its streets, conversation in every conceivable language should hum: parents talking with their kids on the way to school along Greenwich Street in the morning… Businessmen negotiating on Exchange Place in the afternoon… Novelists and artists arguing at cafes, looking out across the East River at night.

To make it that place, people who reflect all the diversity and drive of New York, have to live, work, and visit Downtown. The public sector´s role -- is to catalyze this transformation -- by making bold investments -- with the same sense of purpose and urgency that allowed us to clean up the World Trade Center site months ahead of schedule, and hundreds of millions of dollars under budget. And to be effective, those investments must in turn trigger a response by the private market, that will – through joint public/private initiatives -- create the kind of Lower Manhattan we want.

There are three types of investments the public sector must make now:

Those that (1) connect Lower Manhattan to the world around it; (2) those that build new neighborhoods; and (3) those that create public places appealing to the world.

Let´s start with Connecting Lower Manhattan

Lower Manhattan´s competition to be a global center isn´t just Midtown -- or even Chicago or Los Angeles. Increasingly, it is London, and Berlin, and Hong Kong. In this worldwide competition, easy access is becoming more and more important. We must invest in making downtown more accessible -- both to the rest of the world, and to residents of the metropolitan region.

New York is one of the few premier international cities without a direct mass transit link between its airports and the city center. In London, the time from the city center to the airport is as little as 30 minutes. In Hong Kong, it is 23 minutes. In Berlin, it will soon be 17 minutes. In New York City…it is often one hour or more – and don´t even ask if it is a Friday night or raining!

To make Lower Manhattan a global center, we must have direct, one-seat airport access. Imagine stepping onto an AirTrain or PATH car, and thirty minutes later walking to your gate at JFK or Newark.

How? By extending the AirTrain system -- from JFK through a new tunnel to Lower Manhattan -- and by extending the PATH train -- from Newark´s Penn Station to Newark Liberty Airport. This can be done -- and it must be done.

A big concurrent benefit is for commuters to Lower Manhattan. These same airport connections work both ways – both for travelers and for locals. A new tunnel between downtown and JFK, will connect Downtown to any Long Island Railroad train at Jamaica.

The need is obvious. In 1932 -- the last time mass transit was added to Lower Manhattan -- 63% of residents of the region lived in New York City. Today, that figure is down to 37%. We need to get our workforce from where they now live, to where they still work.

Similarly, via water -- over the last year, we have invested heavily in ferry stations to bring more people to Lower Manhattan -- from more places -- more conveniently. We need to continue to do so, with investments in links to other parts of the five boroughs, regional service to the suburbs, connections to tourist destinations, and potentially to LaGuardia airport. For passengers who are coming from Westchester and Connecticut, we need a new ferry—linked to MetroNorth by a new station on the Harlem River—to bring train riders Downtown 5-10 minutes faster than today, and with a very pleasant ride.

And on the roads: today, over 3,500 buses travel daily to Lower Manhattan, clogging already congested streets. We can´t do without their capacity – but don´t have storage for them mid-day. A new bus parking facility will help keep the streets free and clear by giving those buses a place to go between entering and leaving the City.

Lastly, underground: Construction has begun on a new PATH station at the World Trade Center site, and will begin soon on a new transit hub at Fulton and Broadway. The new stations will untangle the knot of fifteen subway lines that converge Downtown, and then connect to the PATH and AirTrain. Those two stations should also be exhilarating gateways that lift everyone´s eyes and spirits—whether it´s a visitor from Buenos Aires seeing Lower Manhattan for the first time ever, or a commuter from New Jersey seeing it for the first time that day. These stations can be the first of Lower Manhattan´s many additions to the landmarks of tomorrow.

Second… we must Build New Neighborhoods

While the number of people who live below Chambers Street has grown significantly—from 12,000 to 20,000 in the past ten years—other than Battery Park City, for residents there isn´t a there there. No real supermarkets… not enough open space… and not enough schools. And for that reason, families make up a much smaller proportion of the Downtown community than in other communities throughout the city.

With targeted investments, we can catalyze the creation of two exciting new neighborhoods south of Chambers Street -- one near Fulton Street, east of Broadway -- and the other, South of Liberty street, west of Broadway.

Along Fulton Street, the focus for this neighborhood will be a new public square called Fulton Market Square. If you walk along Fulton Street today you´ll see 99-cent stores and vacant storefronts. Fulton Market Square, established as a public market, can begin the transformation of that street, into a great place to shop, see a movie, look at art, or just people-watch.

Re-establishing Fulton Street through the World Trade Center site would make it a thoroughfare that stretches from river to river. With ferry stops on each end -- and two major transit hubs in the middle -- Fulton would join Broadway as one of the two great arteries in Lower Manhattan.

As to the area south of Liberty: Let´s start with the spot where today cars dip into the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel. We propose to build a new park – called Greenwich Square – on a deck over the mouth of the tunnel. Roughly comparable in size to Gramercy Park, Greenwich Square will be one of the City´s green gems.

And to knit the area south of Liberty to Battery Park City, we will make West Street—today, a loud and desolate six-lane highway—into a promenade lined with 700 trees, a Champs-Elysees or Commonwealth Avenue for Lower Manhattan -- as welcoming to walkers as to drivers.

Residents of Battery Park City will finally be able to walk directly east, along an extended Exchange Place, to reach the Financial District and the East River.

To further encourage families to move Downtown, we must build a public library branch and enough schools to accommodate new students, while alleviating crowding in existing Downtown classrooms. And wouldn´t it be great if these schools were part of the World Trade Center site? I think nothing is more appropriate to remember those we lost than to build something for their childrens´ future.

We also have to connect these new Downtown neighborhoods to the existing communities of Chinatown and the Lower East Side. To develop innovative ways to do that, we´ve already formed an inter-agency task force that includes City Planning, the NYPD, and the Department of Transportation. The LMDC also has issued a request for proposals on how we can better link these neighborhoods to the rest of Downtown.

Thirdly…we need to Create New Public Places

New York is New York because it has majestic places open to the public -- that convey the unique thrill of being here. Let me take you on a land-bound Circle Line tour of a re-imagined Lower Manhattan.

Starting at the prow of Lower Manhattan—the Battery—we will build on the successes of the Battery Conservancy, by dramatically reshaping Battery Park to turn what is today just a place to pass through -- into a destination in itself -- a Sheep´s Meadow for Lower Manhattan.

We´ll also extend the plaza in front of a renovated Battery Maritime Building—one of the City´s most beautiful and, unfortunately, most dilapidated structures.

Water Street, today a canyon between office towers, will become a beautiful tree-lined boulevard. On the area´s historic side streets, pedestrians will glimpse something new and marvelous along the East River. It could be, as envisioned by Community Board 1 and the Downtown Alliance, a relaxed place to stroll, with open tables shaded by umbrellas on a sunny day …

Or, if we are bolder -- and if we can find environmentally friendly ways to build in the water -- the City could expand out onto the river, creating something new on every one of these harborside city blocks. New cultural institutions, surrounded by playgrounds, ballfields, open grass, and apartments could look out across the harbor …

Others have suggested that we stretch our imaginations further, and create a wonderland of open space, with a sea-level ice-skating rink, a garden without soil… maybe even a forest of trees.

Whatever we choose, our new waterfront will look out onto ferries crisscrossing among Battery Park, Governors Island, the new Brooklyn Bridge Park, the Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island, even Liberty State Park in New Jersey, knitting these green spaces into a collection of open spaces that are, in total, larger than Central Park.

At the northern end of the new park along the East River, Fulton Street will stretch back to the World Trade Center site, the nucleus of the new Lower Manhattan. Anchoring the commercial and residential neighborhoods, and the restored streets would be a memorial that would put a physical shape to our grief and to our hopes for the future, and give us somewhere we can come together to share our thoughts and reflections on how September 11th affected our lives.

We can link all these places with a pathway that loops down West Street... across the Battery… up Water Street… and back across Fulton to the World Trade Center site.

Traveling around the loop could be shuttle buses, offering an easy-to-use, step-on step-off service -- free of charge. And we can examine innovative ways to manage streets and traffic Downtown, reinforcing the feeling that this is one place. Getting around easily means “community’ – and that´s what we´re trying to create.

Around that loop—only 2.2 miles long—we´ll add to the 20 cultural institutions that already exist Downtown today, creating a critical mass to draw tourists from around the world.

Cultural institutions can animate a neighborhood and define a community. Together, if we could build large-scale performing arts centers people would be on the streets 24/7. Museums – some helping to interpret the World Trade Center memorial and some devoted to already-defined missions – would give further impetus to visit New York´s heartland. And smaller arts centers, would provide much-needed studio and rehearsal space for performing and visual artists, and offer a focus for the dynamism and creativity that define the best this city has to offer.

How do we make this happen?

Done correctly, these public investments will spark a chain of private market reactions.

Over the next ten years—if we make the investments we´ve described—the number of new jobs Downtown will be twice what it would have been, justifying the need for ten million square feet of new commercial space throughout all of Lower Manhattan. New companies, in a range of industries, will grow Downtown -- strengthening the existing financial nerve center -- while diversifying it.

And, as the number of successful companies Downtown increases, Lower Manhattan will become more and more attractive to any company that prides itself on drive and creativity… needs access to a diverse international workforce… and wants its employees in an area that´s not only physically attractive, but exciting.

Many companies have already recognized this and made long-term commitments to Downtown. In fact, I am happy to announce today that Goldman Sachs is reversing its previous plan to move its equity division out of the City, and will, instead, maintain the majority of that division right here in Lower Manhattan. This is just an example of many commitments to come.

New office space will flourish along a commercial area linked by the spine of Broadway. When we finish the new transit hub at Fulton and Broadway, new office buildings and maybe even a new hotel will spring up to the east and to the south, completing the Canyon of Heroes.

As to financing, use of insurance proceeds will help to lower rents, and the new commercial construction can be completed with tax-free Liberty Bonds.

We have already proposed to the federal government a tax plan designed to lure foreign companies to relocate their headquarters to Lower Manhattan. Under the proposal, which we call the “World Trade Center Tax Incentive Zone,’ qualified companies that move their headquarters to the Liberty Zone, would be taxed as if they hadn´t relocated at all, fully protected from the increased federal taxes associated with moving to the United States.

As for housing, with the public investments we are proposing, we believe private developers, some of whom will also use Liberty Bonds, will create at least 10,000 new apartments over the next ten years – over and above the 65,000 new units I announced on Tuesday.

To encourage additional housing, we propose relaxing existing density restrictions on residential development in Lower Manhattan. And we´ll provide developers with a subsidy to make 20% of the new units Downtown affordable to people who couldn´t otherwise live in market-rate housing.

We have catalogued the costs of every one of these improvements—down to the last tree, where possible—and calculated when we would be able to make each of these investments.

We´ve estimated the total cost, in today´s dollars, to be $10.6 billion.

Most of those funds -- $8.8 billion -- will go to the infrastructure we´ve described. The connection to John F. Kennedy airport is the costliest project, the one that takes the longest, and perhaps the one most needed for Lower Manhattan´s future. This would take 9 years at a cost of just under $4 billion. Of course before we start, we must continue to examine all alternatives, including the Super Shuttle, before selecting the project that delivers the most, for the lowest price. But either way, one seat to the plane is key to our success.

Of the funds we´ve received from the federal government, we can use $5.9 billion for this plan. The Port Authority can help too, with passenger facility charges, contributions from its insurance proceeds and from some of the funds it was—before September 11th—intending to spend on the World Trade Center.

We can also use proceeds from the sale of real estate development rights over the transit hub, from Greenwich Square, the East River park, and Fulton Market Square, and taxes from construction at the World Trade Center site itself.

Finally, depending upon what happens with the land swap proposal and with the insurance dispute over one occurrence or two, we could use some of the excess insurance proceeds from the leaseholders at the World Trade Center.

In summary, we might not need any additional funds. But if we do, there´s always the potential of federal or state monies – monies we won´t need until 2009 at the earliest.

Now… this kind of far-reaching, city-changing investment of time and money isn´t going to be popular with everyone. Some people will inevitably pick on a piece of our vision they don´t like, and say we shouldn´t do any of it. Others will point to the maze of rules and regulations, policies and practices, procedures and protocols, and wonder whether we can get this done. And finally, some will just feel scared, which is natural, and they might ask how we can afford to do this at this point in the city´s history.

In fact, listen to these naysayers:

“The very idea is ridiculous.’

“The… scheme is humbug and the sooner it is abandoned the better.’

Those words appeared in the 1850s, and the idea they were talking about, the “scheme’ they derided, was the creation of Central Park. By the time the Park was completed, twenty thousand New Yorkers had carted ten million cartloads of soil by hand to create an oasis the world has never seen, before or since.

If you study New York history, you realize that it is often at the moments when New York has faced its greatest challenges that we´ve had our biggest achievements. Central Park was created on the heels of a financial panic. The subways were built, at the turn of the century, as overcrowding Downtown reached life-threatening proportions. During the Great Depression, New York set the national standard by putting its people to work building parks and highways. The Empire State Building, too, was constructed in just thirteen months during the Depression´s deepest moments.

Again today, New York must transform this City, to prepare it…for the future. We must reinvent Lower Manhattan. We must open the waterfront to the public -- not just in Lower Manhattan, but in Downtown Brooklyn, and throughout the City, wherever possible. We must provide housing for those who want to live in New York, not just in Lower Manhattan, but in all five boroughs. And we must ensure New York continues to lead in the global economy -- not just by reinventing Lower Manhattan, but by creating new business districts throughout the entire City -- including the Far West Side of Manhattan, which can, with an expansion of the Javits Center, drive the tourism industry so crucial to the future of our economy.

There might be those who doubt whether we can set aside our differences, and there might be those who doubt whether we have the stamina required to get this done. But if history teaches us anything, it´s that you should never doubt New York. Never. We can do this—because we have to.

Welcome to a New Beginning for Lower Manhattan.

Possible Rise In Property Taxes (i.e. Rents); Rise In Homelessness

To help cover the city's budget deficit, the Bloomberg administration may increase property taxes by as much as 12 percent this year and 25 percent next year. The property tax is the only city tax that the mayor and City Council can raise without the approval of the state. Council members have reported that the administration has solicited their opinions on a potential increase.

If property taxes rise, homeowners and building owners will not be the only ones paying a bigger bill.

"It will translate directly into rent increases," says Michael McKee, associate director of New York State Tenants And Neighbors Coalition, a tenant advocacy group. "The landlord pays it out of the rents he collects. A property tax increase would result in higher rent increases for just about every category of tenant."

Even rent-regulated tenants would be affected by a property tax increase. The tax makes up about 25 percent of the operating and maintenance costs that the Rent Guidelines Board. considers when establishing annual allowable rent increases. Furthermore, due to the intricacies of the property tax law, rental properties shoulder a higher tax burden than most other residential categories (see New York's Secret Tax.

New York State Tenants And Neighbors will await a formal property tax proposal before announcing its position, but, said McKee, "We might very likely oppose it."

In a rare instance of agreement, landlord groups, such as the Real Estate Board of New York, which represents the real estate industry's interests to the city, state and federal government, also oppose the prospect of a large property tax increase.

"We've said that we would pay a fair share, but a vast real property tax would, in our view, be a very bad thing for the city," said Warren Wechsler, of the Real Estate Board. "Businesses would pack up and go, and residents would pack up and go, and there would be fewer people paying the freight."

A large increase in the property tax would make New York City even less competitive in terms of its tax burdens, said Wechsler. "It would also, in one way or another, impose costs on owners of rental properties that could make it hard to maintain services and keep their buildings up," he said.

Budget watchers believe that spending cuts will come first, and the city will appeal to the state and federal governments for financial assistance. Still, New Yorkers may well end up with some form of tax increase. If the property tax gets the nod, for many, it will come disguised as a rent bill.

More Homeless on the Streets and in the Shelters

Cooler weather has arrived and with it, increasing concern about the number of homeless people on the streets of the city. Anecdotal evidence says that street homelessness is on the rise, and the Department of Homeless Services has seen a corresponding increase in the number of single adults requesting shelter.

The average daily census has been increasing by about 200 people per month over the last few months. While such increases always occur as winter approaches, current numbers are much higher than they have been in past years.

In September 1999, the city sheltered an average of 6,586 single adults each night. This September, it housed an average of 7,650. The Department of Homeless Services has plans to conduct a census of the street homeless, typically single adults who avoid the shelter system, as part of its strategic plan. The agency is overwhelmed by the ever-increasing numbers of homeless families requesting shelter.

"On the family side, the growth has been so accelerated and exceptional," said Jim Anderson of the Department of Homeless Services. "As a result, we needed to open just under 2,000 new units of family shelter since January."

Just one year ago, there were about 6,500 families in need of shelter on a typical night. Now, there are nearly 9,000.

Rebecca Webber is a journalist who has covered housing issues for Gotham Gazette since July 2000.

New York City Goes Wireless

Bryant Park is Manhattan's newest Internet cafe, and it is only the most recent addition to a growing list of free places to surf the Net in New York City. Currently, there are 70 "hotspots" including bars, street corners, parks and other public spaces in Manhattan, Queens, Brooklyn and the Bronx where New Yorkers can get online. Check the map by NYCwireless, a volunteer community group of computer wizards that is partnering with Bryant Park Restoration Corporation and other public organizations, as well as sponsors like Intel, to build these access points.

New Yorkers thrive on mobility, and this now includes the ability to socialize and conduct business while on the move. We have seen the way that cell phones have transformed our conversations and our schedules, which is why one of the first questions typically asked on the phone now is: Where are you?

Now, add the potential to write wireless e-mail and download Web sites and data from your local park using a variety of small portable devices. According to research by New York University's Taub Urban Research Center supported by the National Science Foundation, wireless technologies will have an inevitably greater impact on our lives than the deskbound Internet. With wireless access, our parks could be turned into giant chatrooms or boardrooms.

The wireless network in Bryant Park--which uses radio waves to transmit data to a wireless network card in your laptop--can support 500 users writing e-mails and downloading Internet pages. However, heavy use such as downloading audio or video files could slow down the network. The system uses T1 (high-speed Internet) lines and costs $10,000 to install and $1,000 per month to maintain.

In order to use the Internet from the park, you need a laptop computer and a wireless access card, a card that slides into your computer and communicates with the wireless network. Other small portable devices in addition to laptops such as personal digital assistants and Blackberry's can also be connected to the Internet using wireless networks.

Unlike the rest of the amenities in the park, of course, this is not open to every New Yorker; you still need a laptop. The wireless networks have not crossed the digital divide.

But it is a start Ăś and according to Anthony Townsend of the Taub Center, an important one. "Unwiring our cities will be as important as electrification was at the end of the 19th century," he says. "Cities that provide this amenity will thrive. Others will just get left behind. "