The Tough Budget Choices Ahead

The Independent Budget Office's annual report, http://www.ibo.nyc.ny.us "Budget Options for New York City," comes along at a useful time. With a near or actual recession unfolding and tax revenues declining, it's pretty clear that big budget troubles lie ahead.

But how far ahead? The good news is that there is time to anticipate the worst scenarios. Revenues will be higher than anticipated, according to Independent Budget Office director Ronnie Lowenstein's recent testimony before City Council. This, she said, not only assures a balanced budget for next year, fiscal 2009, but reduces the estimated 2010 budget deficit to a "relatively modest $2.1 billion," far less than the $4.2 billion deficit projected in the mayor's January financial plan.

This gives Mayor Michael Bloomberg another 21 months to establish his fiscal legacy and, unlike his predecessor, Rudolph Giuliani, leave his successor with a structurally sound financial plan.

So it's the 2011 and 2012 deficits -- estimated by the office to be $4.8 billion and $5.1 billion, respectively -- that remain cause for alarm. The state deputy comptroller for New York City's March report, in fact, says the 2011 and 2012 deficits could be as high as $6.6 billion and $6.1 billion. The big problem, as the city comptroller's March report notes, is that in those years the city will no longer have huge annual budget surpluses from previous years to help balance the next year's budget.

Courses of Action

To confront this, the Independent Budget Office offers a range of options that would save or raise $100 million or more. They fall into three general categories: workforce changes, raising revenues and shifts of fiscal burden from city to state.

Each brings its own political problems: Workforce savings generally mean lower worker wages and/or benefits, as well as more work for public employees; shifting fiscal burdens from city to state requires approval by the state; and tax changes hit influential, higher-income taxpayers. The report takes no position on any of the options; rather, it simply provides arguments for and against each one.

Longer Hours, Lower Pay

Extending work hours and cutting benefits for the city workforce would save nearly $1.1 billion a year in 2011 and 2012. Having city employees work 40 hours a week instead of the 35 or 37.5 hours they're currently on the job, would eliminate 7,000 positions and save $456 million. Requiring workers to pay 10 percent of their health insurance premiums - they now pay nothing - would slash $508 million. A 10 percent reduction in supplemental services (dental, vision, prescription drugs, etc.) would cut another $100 million. All these "savings" would have to be negotiated by the city with the public-sector unions.

These plans might win favor with taxpayers-but would no doubt be strongly opposed by the unions. Two additional options, though, might get many taxpayers angry.

One, estimated at saving $300 million, would institute "pay-as-you-throw" trash collection. Owners and renters would be charged by the volume of their trash, much as they now pay for water and sewer services. Adding two students to all general education classes in city public schools would save $177 million.

Raising the Income Tax

With the exception of the post-9/11 2002 fiscal crisis, which prompted a $3 billion tax increase package, the trend in the city and state for the past decade has been to reduce taxes. So one key option in the report would simply raise the income tax rate on higher income New Yorkers, while still keeping it somewhat below rates in effect from 2003 to 2005 and in most of the 1990s.

The budget office lays out a series of interesting progressive options for the income tax, highlighting how un-progressive it has become. (In a progressive income tax, the higher one's income, the higher the tax rate.) Establishing two new rates above the current top rate of 3.65 percent would raise $619 million in 2012.

The new top rate, for joint filers with $225,000 or more in taxable income, would be 3.92 percent; the second top rate, for joint filers' taxable income over $450,000, would be 4.20 percent. Only 7.8 percent of all city taxpayers would pay more personal income tax under this option.

An alternative would lower rates for those in the lower-income levels as well as raise rates for high earners, with a top rate at 4.20 percent. With this option, which would raise $470 million in 2012, 76.8 percent of all tax filers would get a tax cut in calendar 2009. Both of these options would require state approval.

Then there is the commuter tax, eliminated in 1999 by a Republican governor, a Republican State Senate and a Democratic State Assembly. If restored, that 0.45 percent tax on wages and salaries earned in the city would raise an estimated $835 million in 2012.

The Independent Budget Office report offers a second, more progressive commuter tax option that would raise $470 million in 2012. It would tax commuters' wages in the city at a rate from 0.97 percent to 1.22 percent.

Any commuter tax would require state approval.

Looking at Other Taxes

Several other tax revenue and tax reform ideas would also require state approval. Three property tax options would not only raise up to $400 million a year, but would make the city's property tax system more equitable. One would raise the cap on assessments of houses, which currently gives people who have houses a tax break denied those who live in condos or co-ops.

A second takes away a break for co-op owners. Unlike house and condo owners, they currently do not have to pay a mortgage recording tax when the property changes hands. And a third measure would revise the city's co-op and condo property tax abatement program, which currently favors many owners of high-end apartments.

Compared to personal and property tax options, the options for business contributions to revenue enhancement are quite modest. The three biggest ones would raise a total of about $650 million. These are: imposing the sales tax on capital improvements that are now exempt from it; eliminating the insurance industry's current exemption from the city general corporation tax; and doing away with a cap in the general corporation tax that affects about 44 corporations.

Political Pitfalls

If restoring the commuter tax seems a political stretch, two other options in the report could prove even more problematic.

One would shift city funding of Medicaid to New York State. New York City's share - about $5.8 billion in 2008 -- of Medicaid funding is by far the largest share of any local government in the country. In most states the state covers the non-federal share of Medicaid. Under the plan laid out by the budget office, to offset some of the state's new Medicaid costs, New York City would shift half its sales tax revenue to the state. But the city would still come out ahead, reaping a net savings of over $2 billion a year.

There is some recent precedent for such a swap. The state now picks up any increase beyond 3 percent in annual city Medicaid expenditures and recently assumed the local share of the Family Health Care program. According to the state deputy comptroller's March report, this has saved the city $937 million in 2008 and 2009.

The other hot issue in the report calls for tolling of the East River and Harlem River bridges. To help understand the technical and political questions surrounding this, the Independent Budget Office has a separate "Bridge Tolls: Who Would Pay? And How Much." It envisions one-way-only tolls of $8.30 on the East River bridges, and $3.80 on the Harlem River bridges. If city residents were exempt from paying the tolls, the annual revenue from the fees would dip from $830 million to $376 million. This has been floated in the past but could gain more traction with the mayor's congestion-pricing transportation plan on the political table.

The big-money options in report are not all-inclusive. There are other large tax and workforce actions available, including dropping the current 7 percent property tax cut in the January financial plan, further across-the-board cuts or laying off city workers. That usually is the last step in city fiscal crises, but to take only one example, eliminating 8,000 city jobs with an average $60,000 in wages and benefits would save the city about $500 million a year.

Those are the hard political choices ahead. In real budget decision time, the mayor has less than 15 months to tackle them, not only to keep the city on sound fiscal ground but, not incidentally, to set the Bloomberg fiscal legacy.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

After the Boom: Looking Ahead to Tougher Times

Images courtesy of Stock.Xchng and Evan Raskob

While the exact predictions vary, almost everyone agrees the palmy days of budget surpluses and bulging city coffers are coming to an end. Facing declining revenues, Mayor Michael Bloomberg has said the city needs to trim $1.5 billion from its budget over the next two years. As part of this, he instituted mid-year cuts in the city schools, prompting protests from some students and parents.

The news from Albany could be even grimmer. With 20 percent of the state's tax revenues coming from Wall Street, cutbacks seem inevitable. Already Governor Eliot Spitzer has called for scaling back increases in state aid to city schools. He has proposed some new spending initiatives, but many experts say his budget projections are far too rosy.

It is against this backdrop that the city's 2009 municipal elections are beginning to take shape. Five people - three City Council members, a member of the State Assembly and a borough president - have already announced their intention to run for city comptroller. Whoever wins this election - and succeeds William Thompson, who is term limited (and almost certain to run for mayor) will pay a key role in plotting New York's fiscal future. The city's chief financial officer, the comptroller invests its employee pensions funds, audits city agencies and makes recommendations on city programs and spending.

Gotham Gazette asked the five declared candidates for comptroller to offer their views on what policies New York City should adapt to confront the new fiscal reality.

(Note: Other politicians are considered likely to enter the race. We limited ourselves, however, only to official announced candidates.)

Â

Preparing for the End of the Boom

After five years of booming development and growth, the economy is at a crossroads. The crisis in the housing and credit markets is expected to result in a slowdown in growth nationally this year and in lower city tax revenues and jobs generated by our financial services industry.

If elected city comptroller I will fight for policies that support these goals and manage the city's fiscal affairs so that the maximum resources are available to attain them.

Protecting City Pension Funds

As financial advisor to the city's five pension funds, the city comptroller carries the immense responsibility of producing the best possible investment returns on the $112 billion of assets currently in the funds. The failure to do so not only hurts future payouts to retired city employees but can also increase the city's annual contributions to the funds (which are projected to reach more than $6 billion in each fiscal year from 2009 to 2011). While investment returns have been stellar in recent years, the economic downturn poses a significant hazard to the funds and the city's fiscal health.

Through my role as a trustee of the New York City Employee Retirement System for the last six years, I have become intimately aware of the complex decisions involved in investing in global financial markets and am prepared to take on the role of financial advisor. One of the first actions I would take as comptroller is to direct more staff and resources to this function of the office to meet the challenges posed by current economic conditions. I would also continue and accelerate Comptroller William Thompson's policies of protecting our pension investments through shareholder rights initiatives.

Debt and Infrastructure Policies

The city is facing a debt burden that will increasingly restrict our ability to pay for school, housing and economic development initiatives, and other pressing capital needs. This burden will only intensify in an economic downturn. As comptroller, I will advocate for solutions to this problem that include, among other things, increased "pay-as-you-go" financing and a harder look at what capital projects really need to be financed.

Sound Budget Policies

The current law that allows city budget surpluses to be rolled over only into the next fiscal year and not beyond masks serious imbalances between our revenues and expenses and deprives the city of the chance to salt away money during the good years.

In the bad years, the city has often resorted to "one-shot" infusions of cash that only exacerbate future budget deficits. The city needs authority to establish a rainy-day fund, in addition to the city's retiree health care trust fund, that can be tapped for general expenses during the kind of economic downturn we are about to face. While it is not the function of the comptroller's office to create budget policy, I will work for statutory changes that would allow us to create such a fund and avoid the use of one-shots.

Contract and Program Accountability

The comptroller's power to review and audit city contracts and agencies is essential to ensuring a well-managed, efficient city government. During an economic downturn, it is even more important that the city comptroller require city vendors to deliver what they promise and city agencies to eliminate wasteful spending.

As Bronx borough president, I have led the charge in the development of green, energy-efficient buildings in the borough and will vigorously support the movement to more energy-efficient city facilities. I will also continue Thompson's push to increase the accountability of businesses receiving city tax subsidies from the New York City Industrial Development Authority.

A Housing Crisis

The city comptroller's office also plays a limited, but important role in providing direct services to constituents and weighs in on policies having a major effect on city residents. Of particular concern to me is the sub-prime mortgage debacle and the increasing loss of Mitchell-Lama housing in the city. In the Bronx, I have been leading an effort to better coordinate information and services among the various institutions that provide assistance to Bronx homeowners unable to make the payments on their sub-prime mortgages.

As comptroller, assisting homeowners to keep their homes will be a top priority. I will use the bully pulpit to demand that the federal, state and city governments expand their housing programs in the city and create new financing options that help city residents remain homeowners.

I believe that by addressing these issues we can continue to grow a stronger economy and improve the lives of all New Yorkers.

Adolfo CarriĂłn, a Democrat, has served as Bronx borough president since 2002.

Â

Three Steps to Keep the City's Economy Moving

With a sluggish national economy and recession looming, New York City faces a potentially perilous economic future. Because of this, next year's election is so important. While the media's attention will be largely focused on the race for mayor, it is the position of comptroller that can have the most direct impact on the strength of city finances for years to come.

The authority of the office, which includes the power to audit city agencies as well as investment oversight of the $106 billion pension fund, brings with it an immense amount of responsibility. The next comptroller will play a critical role in protecting the solvency and economic vitality of our City.

The situation confronting the next comptroller will depend in large part on the duration and depth of the looming recession. It will take bold vision and creativity to lessen the financial impact on the city and get the engines of our economy moving again. As comptroller, I will push for a three-pronged strategy to: maintain our core tax base, streamline government services to tighten spending and invest in the future.

Keeping Our Tax Base

When New York has faced financial crises in the past, we have seen our core taxpayers -- working families -- driven from the city. No new spending program or bold initiative will be possible if we lose our working families, the heart of New York City. A New York without public school teachers, police officers, firefighters or sanitation workers is not what we want to become. If we are to remain a viable, dynamic, thriving city, we must protect our urban middle class.

As I travel throughout the city, the number one question I am asked is how the sub-prime housing crisis will affect New York. Current trends in the real estate market suggest that Manhattan should remain safe for now, but we need to protect ourselves. It is the residents of the four boroughs outside Manhattan, where most of New York's working families live, who are most vulnerable

The crisis already has had a direct impact on many New Yorkers, from families losing their homes to financing for larger commercial projects proving much more difficult. Nationwide, the domino effect from the sub-prime fiasco is spreading from banks to credit markets to bond insurers to municipal bond ratings, which could devastate the entire financial services industry.

The first step in addressing the concerns of working families is to assist New Yorkers in weathering this. While homeowners throughout the country will need substantial assistance at the federal level, New York can work quickly with major banks and lenders to shore up the housing market here by guaranteeing portions of existing mortgages in exchange for extensions in favorable introductory rates. This will help settle the New York real estate market and send a clear message to affected residents that our city is fighting for them.

Because public education is the cornerstone of the urban middle class, the second key component of keeping our tax base is through a strong public school system. While the jury is still out on many of the Bloomberg administration's education reforms, thanks to the hard work of our teachers and principals, we are seeing signs of progress. In difficult budgetary times, the classroom must remain one of the last places where we cut funding. Instead, we should focus any funding reductions on the Department of Education itself.

Streamlining Service

City government must tighten its belt and evaluate how government services can be provided more efficiently. The first step for the next comptroller will be to use the audit authority of the office to make sure our money is being spent wisely. Comptroller William Thompson has focused on auditing city agencies and making them work more efficiently, a practice that the next comptroller should continue as the city's fiscal watchdog.

In building on these efforts, the comptroller should not only use this authority to streamline city agencies, such as the Department of Education or the Department of Buildings, but also act as an advocate for New York City with Albany. For example, with recent questions on fare hikes and wasteful spending, it is clear that the Metropolitan Transportation Authority needs to be examined regarding providing for fairer treatment to New York City residents. I pledge to fight for the interests of New York City to ensure that every dollar we send to Albany is well spent.

Moving Forward

With our tax base shored up and our budgetary belts tightened, we must work to get the engines of the city economy moving again. The next comptroller should think creatively on how to take advantage of certain economic challenges to turn them to our advantage. For example, the weak dollar abroad has made New York an attractive option for foreign investment. As residents of the financial capital of the world, New Yorkers should embrace globalism and encourage foreign investment to capitalize on the weakened dollar. Americans have sent enough of our jobs overseas. Let's get some of that global investment back and use it to put New Yorkers to work.

While we work to keep New York at the forefront of the global economy, we have to take steps to encourage businesses to remain and grow in the city. An easy first step would be to eliminate the city sales tax, an immediate boost to the retail economy. In addition, the city must develop initiatives for new businesses to move to New York, employ our residents and pay wages that will not only employ but also train workers for advancement.

As Wall Street cools off and construction slows down throughout the city, forward-looking government leaders would be wise to invest in long-term infrastructure projects. These public works projects will keep the momentum of the economy going and keep workers employed. It could also be smart shopping, taking advantage of reductions in construction costs due to slowing commercial activity. Should the private sector slow down due to financing difficulties, opportunity will be ripe for the city to take advantage of lower costs and frontload needed capital projects. This will jumpstart portions of the economy, keep people working and be more cost-efficient in the long run. As a much-needed result, these capital projects -- improved roads and bridges, upgraded sewers and new schools -- will help build a better-running city.

While our City may face a difficult road ahead, New Yorkers have always met challenging times with the strength and perseverance that define who we are. I entered public service more than a decade ago because I wanted to be part of building the future of the City I grew up in and love. I have been so humbled in serving the people of my district in the Assembly, on the City Council, and all of New York as Chair of the Land Use Committee. As we confront this next set of challenges, I hope to be part of building a New York that we can all be proud of as the next Comptroller of New York City.

Melinda Katz, a Queens Democrat, has served on the City Council since 2002 and heads the Land Use Committee.

Â

How to Deal with Declining Revenues

The past several months have been chaotic for most municipal economies in the nation, New York City included. And Mayor Michael Bloomberg's preliminary budget reflects this worsening economic picture. I believe the single biggest challenge facing New York City in 2008 is how to maintain current spending demands on less tax revenue - the fuel that keeps the furnace burning.

There are two issues that severely threaten our revenues, both of which I discuss often as chair of the City Council's Finance Committee. The first is the risks to Wall Street profitability, something most other cities need to worry about only tangentially. Despite starting off 2007 on a strong note - Office of Management and Budget reports that New York Stock Exchange member firms gained more than $8 billion in profits in the first two quarters - the credit crisis that developed over the summer has weakened portfolios.

New York City relies so much on Wall Street profits primarily because it greatly impacts the taxes we collect on income, including bonuses, and on employment generally.

Although bonuses are expected to remain rather steady due to strong performances in early 2007 and strength in sectors unrelated to the credit crunch, we expect an overall drop in financial sector wages. Additionally, the budget office reports that several financial firms have announced or are likely to announce layoffs and reduced staffing, leading to an expectation that financial sector employment will shrink by about 12,000.

The Housing Crunch

The second major risk to the city's revenues is the declining local real estate market. Although this past year the local housing market has been stronger than that of most cities, consumer confidence, lower overall employment and other factors have increased housing supply.

The Office of Management and Budget estimates that single-family home sales will drop about 20 percent in 2008 and that co-op and condo sales, which reached an all time high this past year, will fall measurably.

So with the decline in the city's finances, led by Wall Street instability and a worsening housing market, what can Bloomberg do to steer the city clear of the economic downturn? What wisdom can I or anyone else recommend to stem the downward slide? The answer to both questions is: not much.

A Sneeze to Turn Into A Cold

The plain truth is the city's economy is not exempt from a law of economics: For every up, there is a down. The other plain truth is that mayors have no real control over the duration of these economic cycles.

One of the few things mayors can do, and what Bloomberg is already doing, is working to limit how deeply the city feels the effects of the downturn. This is principally done by tightening spending to maintain a balanced budget. Bloomberg has reduced city spending in the current fiscal year and in the next. I'm not happy with all the cuts, and I've vowed to fight the most unpalatable ones. These include cuts made to the Runaway and Homeless Youth program, geriatric mental health and the Autism Initiative, a $1.5 million program I created last year that lends educational and emotional support to affected children.

Another of the few things mayors can do, particularly during a recession, is, of course, raise taxes to make up for revenue shortfalls. Bloomberg did this by way of raising property taxes during the 2001 recession. None of us at City Hall want to do that this time around.

It remains to be seen how much worse the economic scenario gets before this option becomes a viable idea. Just as Bloomberg has said, the next few months will shed light on the many tough decisions ahead. In the meantime, I've said often that a tax increase is on the table only as a last resort.

Not Looming, But Here

So, you'll notice I've used the "R" word. Some cities have already been claimed by recession. Many analysts say Detroit, with its rate of housing foreclosures in the double digits and its high unemployment, is already in recession. San Francisco, Cleveland, and Miami are a few others being watched closely for symptoms of acute recession. Is New York City soon to join the list? The city is in an economic downturn, to be sure, but based on the current data, I don't think we'll fall into actual recession.

We might be lucky this time. One of the many things I've advocated for at the City Council is to use our surpluses in the smartest manner possible. Pre-paying some of our obligations, including placing $2 billion aside for retiree health expenses, when we had surpluses has proved helpful to us now.

Amid the doom and gloom there are some economic bright spots for the city -- including that our tourism industry is booming. We can thank our superb attractions and the weak dollar for that. NYC & Co., the city's tourism agency, predicts that the city welcomed a record 46 million tourists, many of them international visitors, in 2007. And all signs continue to point to similar tourism rates over the next couple of years.

A strong tourism industry plays a vital role in sustaining the city through the lean times, because it keeps hotel taxes, sales taxes and employment humming. There are also some sectors of the economy that continue to grow regardless of the current economic cycle. Demand and employment in both the education sector and health services sector remains strong.

The Comptroller's Role

Is there any role to be played by the city's next comptroller in ameliorating the effects of the ongoing downturn? The office of the comptroller is involved in the issuance of General Obligation bonds, setting the terms and conditions for all debt, analyzing contracts and auditing programs and agencies, and is the investment advisor and custodian of the city's pension funds. Within each of these responsibilities and in varying degrees the comptroller can join the mayor to also limit the effects of the downturn. Scrutinizing spending is one responsibility the comptroller can implement rather swiftly. I already do that in my role as chair of the City Council's Finance Committee.

Apart from official functions of the city's comptroller, there is a more nuanced yet potent function. As the finance specialist for the city, the comptroller is in an excellent position to advocate fiscal policy that would cushion the blow of economic downturns. One such policy I've consistently called for is the creation of a Rainy Day Fund, which requires state legislation. This savings account would be funded over a period of years with budget surpluses to aid the city during lean times.

A Rainy Day Fund would not only cushion services during downturns, but, assuming it would replace the current practice of rolling prior year surpluses into the next, it would also make the city adopt a budget that more accurately reflects our current financial status. Additionally, the comptroller can use his or her position to advocate for reduced reliance on non-recurring revenues to balance the budget, something that has occurred too often and will be untenable in coming years.

The final analysis for comptroller ought not rest on what he or she can do during tough times, because the official tools at his or her disposal are very limited. Rather, the analysis ought to rest on what skills the current and future comptroller possesses in order to understand and deftly manage the effects of economic downturns. As someone who has spent more than 20 years on and off Wall Street as an expert in municipal finance and who has served as chairman of the City Council's Finance Committee, I will bring to the comptroller's office a host of related experience.

David Weprin, a Queens Democrat, has served on City Council since 2002 and chairs the Finance Committee.

Â

Changing the Way the City Does Business

New York City is facing some tough economic times.

Everyone knows the basics by now: Foreclosures are way up; Wall Street has already begun layoffs, with more to come; and the debt crisis is not only roiling the financial markets, but is starting to affect the city's cost of borrowing. Virtually all economic analysts agree that in the near and medium-term, current forecasts for growth and revenue are likely to prove optimistic -- all the risk is on the downside.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg's preliminary budget issued in January reflects these realities and prudently begins to adjust for the slump. But the real task for those of us who lead the city government is to take our current difficulties as an opportunity for much deeper rethinking of our budget policies.

There are many avenues to pursue, but I want to highlight five priorities: rooting out wasteful spending, eliminating corporate welfare, reforming the budget process, diversifying the city's economy and making our tax code fairer.

Cracking Down on Spending

We must be far more aggressive in reducing spending on programs that don't achieve their stated goals or that do so inefficiently. For example, I recently went after a poorly designed affordable housing program called "HomeWorks/StoreWorks," which cost the city more than $500,000 per apartment. After publicity exposed this boondoggle, the department of housing preservation and development terminated the program.

Sometimes government costs are inflated not just by inefficiency, but by actual fraud. To crack down on this, the City Council in 2005 passed a bill I authored called the "False Claims Act" that allows whistleblowers to initiate suits against contractors who have been ripping off the government. The bill was modeled on a successful federal statute that has been used to recoup funds from fraudulent defense contractors and health maintenance organizations. Unfortunately, the city's Law Department insisted on watering down the bill with a provision allowing the department to block the whistle blower suits-and the department has abused this authority by blocking every single suit initiated so far. The City Council's Finance Division estimates that, if properly implemented, the bill would save taxpayers $30 million a year. We should go back and reinstate the original, stronger bill.

Ending Corporate Tax Loopholes

We should also eliminate corporate welfare. Last year, I joined with Councilmembers Annabel Palma, Letitia James and others to repeal a loophole that allowed developers to put up new luxury buildings and pay no property taxes on them - the so called "421-a" law. That reform will bring in at least $500 million dollars over the next five years. The next step is to reform the Industrial and Commercial Incentive Program, a similar loophole for commercial development.

Of course, the single biggest example of corporate welfare is the proposed Atlantic Yards development. The Bloomberg administration has agreed to give the project's developer at least $100 million in direct subsidies, plus another $400 million to $500 million in tax breaks. In the current financial climate, this handout is impossible to justify.

Reforming the Budget Process

Beyond tightening spending and eliminating unnecessary tax handouts, we should also reform the budget process itself. City Council Speaker Christine Quinn has made great strides toward a more transparent budget, and we can build on her accomplishments.

We must break down the budget into specific spending items for each individual program, rather than grouping things in big lump sums, called initiatives. We should also end the practice of negotiating budgets behind the scenes and then simply holding an up-or-down-vote at the end of the day. Instead, each City Council committee should vote on the budget for the agency in its jurisdiction-and the committees should be permitted to add new spending only if they find offsetting cuts.

A More Varied Economy

We need to renew our focus on diversifying the city's economy. Turmoil in the financial markets only underscores how dependent we are on banks and investment firms. The financial sector will and should remain the heart of our economy, but city policy should be directed at helping other sectors grow as well. Our highly successful film production tax credit is a good example of an initiative that has created good-paying jobs for skilled and semi-skilled workers outside of Wall Street.

Another, similar opportunity is shipping. Instead of trying to squeeze out the city's remaining container ports, as the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey has misguidedly done, we should help them expand.

Taxing Income

Another urgent priority is to make the city's income tax fairer. The current downturn is hitting low-income families the hardest, and our first impulse should be to ease the pain. One concrete and immensely useful step would be to give tax relief to the city's working poor.

Astonishingly, more than 600,000 New Yorkers live in households that are too poor to pay any federal or state income taxes - but are nonetheless required to pay the New York City income tax. This is mostly due to the fact that the federal and state tax laws provide a far more robust Earned Income Tax Credit than does the city tax code. The Earned Income Tax Credit is one of the best innovations of progressive government - it rewards those who, in President Bill Clinton's words, "work hard and play by the rules." We should beef up the city's tax credit to put much-needed dollars into the hands of the city's working families.

The boom of the past few years has been good for the city, and we all wish it had continued. But it also allowed us to defer some difficult choices. In this, more challenging period we will have no option but to confront our structural budget problems.

With innovative and decisive leadership, we cannot just slog through the fiscal slump, but we can thrive despite it.

David Yassky, a Brooklyn Democrat, has served on City Council since 2002 and chairs the Small Business Committee.

Â

Bringing Insurance to Small Business

City Council Speaker Christine Quinn endorsed the creation of a citywide ferry service and an expansion of a small business insurance program in her State of the City address last week. Now advocates and stakeholders are weighing in, and - for the most part - appear to be praising the proposals.

At Cartridge World, a downtown Brooklyn firm that sells new and refurbished cartridges for photocopiers, printers and fax machines, the cost of health insurance for owner Geoff Wood’s three employees seemed sure t empty his pockets. When Wood initially looked into comprehensive health insurance plans, they exceeded $500 per employee per month.

Thanks to a health insurance program created for Kings County businesses by the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce, Wood was able to get more affordable coverage for his employees, saving him more than 50 percent in premium costs. This made his employees not only happier, but healthier. According to Wood, his employees “were less likely to leave because they had good health benefits.” For Cartridge World this translates into increased employee satisfaction and higher productivity.

In a recent survey conducted by the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce, an overwhelming majority of small businesses support universal healthcare and want to offer coverage to their employees.

The problem for owners like Wood and other Kings County businesses is that it can often be difficult to afford. But Brooklyn HealthWorks, the insurance program founded by the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce, can provide an interim solution as the nation debates how we can cover more workers - whether through mandates or a free-market based system or a combination thereof.

And soon, small businesses in other boroughs will be able to reap the benefits, including attracting and retaining qualified employees.

Beyond Brooklyn

Last week in her annual State of the City Address, City Council Speaker Christine Quinn proposed an expansion of Brooklyn HealthWorks into Manhattan and Queens. Quinn’s speech balanced a call for continued fiscal responsibility with initiatives to stimulate the local economy, protect affordability and support New Yorkers.

Under the speaker’s plan, the city would subsidize premiums for businesses in Queens and Manhattan. Based on Brooklyn’s experience with HealthWorks, upward of 600 new businesses are expected to enroll in Manhattan and as many as 300 businesses will enroll in Queens during the first year alone. This equals an additional 4,500 New Yorkers with employer-based coverage. Citywide expansion is expected to follow and will further increase the number of New Yorkers with health insurance coverage. Since Quinn’s address, Brooklyn HealthWorks has received inquiries from small business owners and brokers in Manhattan and Queens - all looking to learn more.

A History of Health

In 2004, with the help of the New York State Insurance Department, the chamber created Brooklyn HealthWorks, a private-label Healthy NY insurance product. Brooklyn HealthWorks allows eligible small businesses in Brooklyn to offer affordable health coverage to their employees and dependents at lower premium rates than other small group plans because of premium subsidies made available by the state. Brooklyn HealthWorks currently covers approximately 180 small businesses, including more than 850 employees and their dependents.

Brooklyn HealthWorks builds on the success of Healthy NY by offering a plan that eliminates hospital co-payments that run between $500 and $900 per occurrence for Healthy NY plans. Brooklyn HealthWorks also does not dictate how much an employer must contribute to premiums. For Healthy NY, businesses are required to contribute at least 50 percent of the cost of individual coverage. Finally, Brooklyn HealthWorks provides coverage to independent contractors (1099 employees) who work at least 20 hours per week at small businesses that also cover traditional (W-2) workers.

The same eligibility requirements will apply for an expanded HealthWorks program: A business must have a location in the participating borough with 2 to 50 employees and have not provided comprehensive health coverage during the last year (or have contributed less than $75 per employee per month). Additionally, 30 percent of the company’s employees seeking coverage must earn $36,500 or less annually. For businesses that qualify, healthcare savings can be reinvested into employee training programs, promotion and the creation of new partnerships with other local businesses—all of which stimulates economic growth.

HealthWorks operates in partnership with Group Health Incorporated. Businesses with access to HealthWorks coverage are able to obtain care at over 142,000 provider locations throughout the tri-state area, all without the need for a referral. Some of the benefits included in the plan are physician services, hospitalization, prescription drug coverage up to $3,000 annually, maternity care, emergency services, and diagnostic X-ray and laboratory services.

The Brooklyn-based program has changed and grown over the years, but because of permanent funding streams – secured with the assistance of Brooklyn legislative leaders such as Assemblymember Joseph Lentol and Senator Martin Golden – it continues to flourish. We are confident HealthWorks will continue to address the affordability of healthcare for small businesses in Brooklyn and beyond.

Carl Hum is president and chief executive officer of the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce. Â

Tax Breaks - Who Wins and Who Loses?

Mayor Michael Bloomberg's January Financial Plan for the next four fiscal years repeats the message of last October's budget modification: The economy is slowing, city tax revenues are down, and it's time to make budget cuts. The mayor balances the preliminary $58.5 billion budget for 2009 through agency spending cuts over the next 18 months and the use of surplus funds from last year. The four-year plan, however, projects deficits of $5.6 billion in 2011 and $5.3 billion in 2012.

Excessive cuts for commercial interests seem to have caught the attention of the City Council, if only in its recent near-unanimous vote to end the 25-year-old property tax exemption held by Madison Square Garden (a vote that is meaningless unless the state legislature and governor also act). Testimony at the council on the garden's tax break also called attention to much larger commercial tax breaks that also could use council review.

A variety of tax cuts and breaks - including the $400 property tax rebate - cost the city revenues. With no significant service initiatives or increases in the preliminary budget for 2009 - and education cuts that look like a major retreat from an earlier mayoral priority - it's a good time to look a little more closely at city tax breaks in general. Who wins, who loses, and what are the costs?

Billions of Breaks

The city's recently updated Tax Expenditure Report for fiscal year 2007 provides a useful window into the billions of dollars in city tax breaks - commercial and residential property taxes in particular.

Many seem likely to remain during the widely predicted economic downturn. The mayor's financial plan extends the big property tax cuts in the current fiscal year through all four years. Next year's property tax cuts -- the $400 rebate for homeowners and a 7 percent property tax rate cut -- will cost over $1.3 billion in lost revenues. This almost dollar-for-dollar underwriting of tax cuts with agency cuts in 2009 will presumably be controversial at the City Council, setting the stage for the annual "budget dance," in which the mayor diverts the council from larger issues by slashing council initiatives, which the council then fights to restore.

The city took in about $13 billion in property taxes in 2007. All the individual property tax breaks add up to $3.3 billion in lost revenues. This does not include the 7 percent rate cut, but does include the $256 million cost of the homeowner rebate, the $311 million property tax abatement for co-op/condo owners (a 1996 "temporary" council plan to narrow the property tax burden between those owners and house owners that keeps getting extended).

Business income and excise tax breaks added another $573 million in lost revenues (in 2004). The largest of these remains the $248 million that insurance companies saved because they do not have to pay any city business income tax.

Commercial Tax Breaks

At the January 7 City Council hearing on ending the Madison Square Garden $12 million property tax exemption - granted in 1982 when the Knicks and Rangers threatened to leave the city - Bettina Damiani, director of GoodJobs New York, an advocacy organization, asked the council to review much larger questions of tax expenditures (a technical term for tax breaks) granted by the city's Industrial and Commercial Initiative Program.

The tax expenditure report notes that 5,771 exemptions and abatements under this pogram cost $410 million in lost revenues in 2007. Good Jobs New York argues that the initiative program, which was intended to help small firms outside the core Manhattan commercial district now includes benefits for "some of the priciest commercial districts in the city," including $14 million in tax breaks in 2007 for properties in mid-town Manhattan.

These tax breaks rarely get any review. The 2007 tax expenditure report does not feature any independent comment by the Department of Finance, which publishes the report, and offers only a single "evaluation" of business tax breaks. That's a one-page summary provided by the mayor's Economic Development Corporation of its Local Law 48 report for 2006, which is supposed to track the costs and benefits of the development corporation's tax exemptions. This mini report makes two extraordinary claims.

It states, "The present value of city benefits [from 631 EDC investment projects] is estimated to be $23.9 billion, over 34 times the value of city costs."

Further, it contends, "The projects will return a cumulative net benefit to the city (city benefits minus city costs) of approximately $3.2 billion."

If the council wants to pursue serious review of economic development projects, those claims would be a good place to start.

The 7 Percent Property Tax Rate Cut

Beyond the breaks, the across-the-board 7 percent cut in the property tax rate cost about $1 billion this year (Note: The January Finance column incorrectly reported it was $750 million).

The mayor's financial plan does acknowledge the current economic and fiscal uncertainty by making the 7 percent property tax rate cut conditional on the overall fiscal picture. The key variable is anticipated - but uncertain - state and federal aid. Already the mayor has complained in Albany that Governor Eliot Spitzer's state budget proposal shortchanges the city by at least $500 million.

For all the money it costs, though, the rate cut provides very modest benefits to taxpayers. In total dollar gains, it primarily benefits commercial properties because they pay the lion's share -- over 40 percent -- of the city's property tax -- although their properties represent only 22 percent of the market value of all properties in the city.

One-, two- and three-family houses, co-ops and condos together represent over 55 percent of the total market value of city properties, but their owners pay only 15 percent of the tax levy. That's good for residential owners, but on the flip side, in the aggregate, they get less of the benefit from an across-the-board cut than commercial owners.

George Sweeting, deputy director of the Independent Budget Office, explained in a New York Post op-ed last summer that most property owners saw little change in their tax bills after the cut. Owners of houses, for instance, saved an average of $43, or less than 1 percent. Condo owners got a $99 average benefit, and the average co-op owner had virtually no reduction. The reasons for these minimal gains are very complex (and desperately in need of simplification) but a key one is that assessments on average grew by 8 percent, while the rate cut was only 7 percent.

Put another way, the commercial benefits of the rate, while nominal for individual property owners, add up to a cost of some $400 million in lost revenues - while the new budget proposes cutting $324 million from education and hundreds of millions in other areas.

At the same time, the city's more progressive tax breaks, such as the $73.5 million for nearly 100,000 senior and veteran homeowners, the $86 million in rent-savings for 45,000 low-income seniors, and the $65 million (in 2004) in earned income city tax credits for 734,000 low-income working individuals, tend to be modest and dwarfed by big-business breaks.

There are many good arguments for the residential property tax breaks, such as the burden of the city personal income tax and other taxes. But the lack of tax relief for renters who are not senior citizens makes the owner benefits look unfair.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

Stimulating the Economy

Plummeting financial markets have increased the urgency of calls for a federal fiscal stimulus package to provide a temporary boost to consumer and business spending. This comes as the collapse of the housing market, weaker than expected holiday retail sales and declining employment have combined with turmoil in the financial markets to heighten the likelihood of a recession.

On the "monetary policy" side, the Federal Reserve has been taking unprecedented actions, notably dropping a key interest rate last week following stock market swoons around the world as fears spread regarding the global effects of a slowing U.S. economy. On January 24, the White House and the leadership of the House of Representatives said they had reached tentative agreement on "fiscal policy" action by the federal government, hoping to to jump-start the economy. It would feature a package of individual and business tax cuts costing $150 billion - an amount equal to roughly 1 percent of gross domestic product. Since the announcement, though, Bush-House proposal has come under criticism, and some senators have proposed various modifications that should come up for a vote within the next week. There will be intense pressure for the House and the Senate to then quickly reconcile their differences in order to speed passage of a plan in the hopes of moderating the sinking economy.

What's in the Bush-House stimulus package and how might it be modified in the Senate? Will it "work" in turning the economy around? How will it affect New York's economy?

The Bush-House Stimulus Plan

The plan announced on January 24 by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson would provide tax rebates to households and tax breaks to businesses. Bowing to widespread pressures, President George W. Bush backed away from his earlier plan to link any stimulus to extension of his signature tax cuts, now set to expire after 2010. Under the plan, married couples with incomes up to $150,000 would receive a rebate equal to 10 percent of taxable income up to $1,200; the rebates would then phase out so that very high-income households would not receive anything. For single people with incomes up to $75,000, the rebate would be a maximum of $600.

In a concession to House Democrats, the president agreed to include a rebate for low-income households who owed no federal income tax in 2007 but who had at least $3,000 in wage or self-employment earnings. For these wage-earning couples, the rebate would be a minimum of $600 ($300 for singles). In addition, any household with at least $1 of income tax rebate would receive $300 for each child.

The Treasury Department indicates that rebate checks would not be sent out until late spring at the earliest.

The Bush-House plan to stimulate business investment includes "bonus" depreciation and a doubling of the amount that small businesses can claim as an "expense" and so deduct from annual income. Both measures would lower business' 2008 tax payments by a total of $43 billion. The Congressional Budget Office concluded that such business investment incentives have modest effects at best. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has noted that 35 states, including New York, would likely lose revenue from state corporate income taxes if these business investment incentives were enacted since these states base their taxes on the federal definition of income.

What the Critics Say

While there is broad support for quick action to stimulate the economy, many economists and fiscal analysts have criticized the Bush-House plan on the grounds that it is poorly targeted and will not provide the maximum economic boost given its cost to the federal treasury. Senators are being lobbied furiously to make improvements. New York Times columnist Paul Krugman notes that the Bush-House plan would send "the bulk of the money to those who are doing OK financially." Indeed, the Tax Policy Center estimates that 58 percent of the individual rebates would go to the upper and upper-middle class (the top 40 percent) while the poorest 40 percent would get less than 21 percent of the total. (The middle 20 percent of households would get a roughly proportionate 21 percent of the benefit.)

Most economists agree that a stimulus directed to low-income households will generate a bigger spending impact than one aimed at higher-income households since affluent people are more likely to save the money, rather than plow it back into the economy. In assessing the relative merits of various stimulus approaches, the Congressional Budget Office recently gave high marks for cost-effectiveness for a tax rebate "focused on people who are likely to spend it." And none other than Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke urged that any fiscal package should be "efficient, in the sense of maximizing the amount of near-term stimulus per dollar of increased federal expenditure."

With the widest income gap in the nation, New York State has large shares of both rich and poor households. A tax rebate that reaches low-income people is more likely to stimulate New York's economy than one aimed at the rich for the simple reason that low-income households are more likely to spend all or most of their rebates than households at the high end of the income spectrum. One important caveat, though: To boost the economy, the money has to be spent on goods and services produced in the United States. If it goes toward the purchase of imported products, the economic benefit largely will "leak" out of our economy.

Ideas from the Senate

Any plan will have to win approval from the Senate, some of whose members have other thoughts on how to stimulate the economy. New York Sen. Charles Schumer, chairman of the Joint Economic Committee, said over the weekend that the Senate was likely to add an increase in unemployment benefits to the Bush-House stimulus plan. Greater spending on unemployment benefits would generate "more bang for the buck," said Schumer.

Unemployment insurance is a major "automatic stabilizer," providing partial income replacement for workers who lose their jobs. Most proposals for increasing unemployment benefits involve having the federal government fund benefits beyond the 26 weeks of payments financed through state unemployment funds. This would help New York State since 85,000 New Yorkers will exhaust their state unemployment benefits in the first six months of 2008, according to the National Employment Law Project.

An increase in food stamps to boost spending by low-income households is also actively being considered in the Senate, according to Schumer. Food stamp benefits go almost entirely to households subsisting below the federal poverty line. With rising food prices and reports that many low-income households run out of food by month's end, increasing the monthly allotment would both help low-income households and the economy. Over 1.8 million New Yorkers receive food stamps, including 1.1 million in New York City.

Support for increased unemployment and food stamp benefits crosses the aisle as Republican Senators Susan Collins and Olympia Snowe of Main have pledged to add funds for these benefits, and a bipartisan coalition of Northeastern and Midwestern senators will push for additional heating assistance for the poor. At a Senate hearing January 24, Peter Orszag, director of the Congressional Budget Office, testified that increases in unemployment benefits and food stamps would have a more immediate impact on the economy than tax rebates. "Food stamps and unemployment benefits can affect spending in two months, (while) rebates would affect spending at the end of 2008," he said.

Republican Governors Want Relief

The sagging economy, particularly the housing slump, has already started to be a serious drag on state and local government budgets in many parts of the country. If state and local governments, facing a decline in tax revenues, cut spending or increase taxes, that could further contract the economy. Columbia University's Joseph Stiglitz, winner of the 2001 Nobel Prize in Economics, has urged that any federal stimulus include fiscal relief to state governments. States don't have the luxury the federal government has in that states have to balance their budgets. The housing crash and economic slowdown are already forcing states to "respond by cutting spending, and this acts as an automatic destablilizer," Stiglitz wrote. Federal help could forestall those cuts.

Among others, Republican governors from California, Florida and Minnesota, have called for a temporary increase in the federal share of Medicaid expenditures to help them deal with yawning budget gaps. (Federal and state governments share the cost of providing health care to low-income Americans.)

To counter the prolonged economic weakness coming out of the 2001 recession and the accompanying fiscal pressures on states, Washington enacted $20 billion state fiscal relief stimulus package in early 2003. Half was used to increase the federal matching rate for Medicaid, and half was provided in the form of flexible grants to the states. Given the size of New York's Medicaid program, the increase in the federal Medicaid matching rate was particularly beneficial to New York. Every dollar of federal aid keeps a dollar of spending in the economy rather than forcing cutbacks or tax increases to maintain services and spending.

Adding Infrastructure?

Increasing spending on public works like roads, schools and other facilities is often considered a way to prime the economic pump. In their $140 billion federal stimulus proposal released earlier this month, the Economic Policy Institute recommended $40 billion to accelerate public infrastructure repairs. Because infrastructure spending would speed up needed investments that support long-term economic growth and are less likely than other kinds of expenditures to “leak” out of the U.S. economy through the purchase of imports, many economists -- and some senators from both parties -- argue that a significant infrastructure spending plan warrants inclusion in any stimulus package.

Mortgage Foreclosure Relief

The depressed state of the housing market could retard the economy's ability to recover. Normally, sharply declining interest rates induce first-time homebuyers to take out mortgages and then spend money on furniture and appliances for their new homes. This time, though, the decline in interest rates might not have that effect. After years of over-heated expansion, the housing slump is likely to continue for some time. Plus, tens of thousands of homeowners saddled with unaffordable sub-prime mortgages will lose their homes through foreclosure, keeping prices and expectations down, slowing any rebound in the real-estate market.

Housing plays a key role in the national economy and shapes consumer expectations, making it essential that the government take action to stave off an epidemic of foreclosures and help the housing market recover. Government actions proposed so far, though, do not appear sufficient to turn around the market.

Just because New York City has not yet seen real estate values plummet does not mean that mortgage foreclosures are not a huge problem. Reckless and unregulated sub-prime lending has been widespread, particularly in neighborhoods of color in Brooklyn and Queens. Data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York indicate that 20 percent of adjustable rate sub-prime mortgages made in New York City are already in foreclosure with more on the way. The economics consulting firm Global Insight predicts that there will be 50,000 foreclosures statewide in 2008 and that home values in New York will fall by $63 billion this year.

Turning the Economy Around

By itself, a federal stimulus package, even if modified in the Senate to provide more immediate and better distributed relief, probably will not resurrect economic growth. But a timely and targeted stimulus package is essential to significantly moderate some of the current downward economic pressures. The economy nationally and in New York will benefit to some degree. A smart fiscal stimulus package that boosts spending could provide an important complement to the aggressive monetary policy moves taken by the Federal Reserve over the past two months to ameliorate the credit squeeze and the decline in the housing market.

Fiscal stimulus would remove some of the burden on the Federal Reserve to bring down interest rates. Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers notes the risks inherent in a policy of "excessively" low interest rates: downward pressure on the dollar likely to fuel inflation and another speculation-induced bubble.

As the home of Wall Street with its out-sized economic role, New York's long-run economic fate also depends on a new regulatory regime that will restrain Wall Street's bubble-making tendencies. Long-time financial market sage Henry Kaufman recently called for a thorough-going regulatory review of what went wrong on Wall Street. The current financial turmoil underlies once again, the need for New York City and the state to develop a set of policies to diversify the local and state economies and need to create more sustainable, good-paying jobs.

James Parrott is deputy director and chief economist of the Fiscal Policy Institute (www.fiscalpolicy.org). He has been studying and writing about the New York economy since he landed in New York City a quarter century ago.Â

A Bad News Budget

New York City should get ready to lose some weight. This time, though, the target is not New Yorkers binging on transfat-laden fries or sugary soft drinks. No, now it's government that has to slim down.

For the first time since 2004, the city faces, not a surplus, but a deficit, forcing all departments and agencies to cut back or suggest innovative revenue producing proposals. No agency goes untouched. No department has immunity.

Calling recent economic trends "disturbing," Mayor Michael Bloomberg calmly went through financial indicators on Thursday, reminding New Yorkers that the city faces the effects of the national economic slowdown. "It's going to hurt us," warned the mayor, while ticking through a fairly pessimistic Power Point presentation at City Hall.

The question is, how much?

Five months before the City Council must approve a balanced budget, the mayor's preliminary proposal provides some indication of what some New Yorkers might have to do without next year and additional fees they might pay.

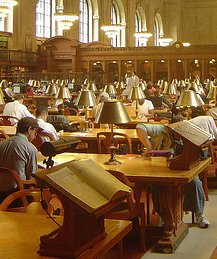

Photo (cc) 2007, kebella/ Nicole.

Bloomberg contends that essential services will not be cut, but he needs to trim a total of $1.5 billion over the next two years. He plans to cut funding for individual schools and close some homeless shelters among other reductions. He hopes to boost the tax on cigarettes once again. But he still intends to keep the $400 tax rebate and 7 percent property tax cut implemented last year -- though some advocates cautioned against that.

The administration needs to fill in many of the details. City Council members, advocates and others are just beginning to mull over what is and what is not included for fiscal '09. And budget watchers wonder whether the mayor has planned for the future or simply offered a quick fix.

A Foggy Forecast

The http://www.nyc.gov/html/om/html/2008a/pr029-08.html&;cc=unused1978&rc=1194&ndi=1">budget, an increase of 3.7 percent from fiscal year 2008, tops $58.5 billion. Much of the increase is due to contract agreements with city employees, debt services and pensions. The figures announced Thursday incorporate the mayor's departmental directives from last fall, when he required every city department to cut spending by 2.5 percent this fiscal year and about 5 percent in fiscal year 2009. (Bloomberg said last week that agencies had cut a total of 4.3 percent for this upcoming fiscal year - slightly less than he requested.) Unlike in some previous years, schools and police will be forced to cut back along with everyone else.

The city's expenditures are pretty predictable, said Bloomberg, but revenues are not. Almost every expert, though, predicts a downturn from the mortgage meltdown, credit crunch and Wall Street's seesawing.

New York Stock Exchange firms saw their largest losses ever in the third quarter of 2007, said Bloomberg, and the news for the fourth quarter is shaping up to be even worse. Unemployment claims are up nationwide, and housing sales have steadily dropped. Politicians in Washington are so worried that they seem to have put their partisan differences aside to reach agreement on a $150 billion economic stimulus package.

Budget officials estimate the city will receive $660 million less than anticipated in revenue based on the decline in profits on Wall Street.

So, what's the good news? Well, the mayor said, the budget is balanced. (By law, it has to be.) Tourism in the city, and hotel and office occupancy rates remain high. Bloomberg also made sure to give himself a pat on the back for prudent fiscal planning during the city's good times, when he put aside millions to pay down debt in future fiscal years.

Where to Cut

This year's budget poses some quintessential policy questions the city did not have to face during the boom of the past few years: Should the government cut services to preserve tax cuts or should it keep programs at their current level and roll back tax breaks? And if the economy continues on its gloomy trek, what could or should the city do to avoid a far greater economic slowdown?

The answers depend to some extent on how bad things get. Some take a very grim view. Speaking at a forum Friday night, Representative Jerrold Nadler said the country could be facing the worst economic downturn since World War II. Bloomberg, while hardly optimistic, is not that gloomy.

"He's certainly put up big yellow lights, but he hasn't waved the red flag and said everything is falling apart," said Doug Turetsky of the city's Independent Budget Office. "Assuming there are no big local economic surprises over the next few months and things don't get remarkably worse, we're basically still running off the momentum of the good times. What the mayor's clearly showing us is even if things don't get worse, the days of wine and surpluses are over."

Turetsky said keeping the city's $400 tax rebate and the 7 percent tax cut on the table is also a viable option. That is, if the city's economic outlook starts to improve or, at least, not get demonstrably worse.

Some city officials are hopeful. Councilmember Domenic Recchia predicts the markets will recover and funding will be restored before it's time to finalize the budget. "I think that 5 percent is not going to be 5 percent," said Recchia, who chairs the council's Committee on Cultural Affairs, Libraries and International Intergroup Relations, of cuts to the city's cultural programs.

Other experts, though, see the budget as not doing enough to address the tough times that could lie ahead. Bloomberg's proposal uses the city's previous surplus to balance the budget in fiscal year 2009, which runs from July 2008 to June 2009. Then little of the city's surplus will remain. Because of that, some experts see a $4.2 billion gap looming in fiscal year 2010 and want the mayor to think about that now.

Charles Brecher, research director at the Citizens Budget Commission, would prefer to see the surplus money spread out over several years and not used for 2009 alone. "We kind of see this as temporizing and not dealing with the fundamental problems," said Brecher. The commission, he added, will draft alternative options for the City Council and the mayor to consider, including examining premiums in the city's health care system, like requiring employees to chip in, and curbing spending more aggressively.

Doing the Dance

Beyond its effect on spending and taxes, the new economic reality could change the relationship between the mayor and the City Council. The City Council must approve the budget. Over the past few years, with the city's coffers overflowing, the budget back and forth between the administration and council has been relatively congenial. But now that programs are threatened, some members are preparing to strap on their tap shoes.

"Let the dance begin," said Councilmember Vincent Gentile.

This refers to the infamous budget dance, long a mainstay of city politics. The administration cuts certain programs, libraries for instance, knowing the City Council will reinstate them. The mayor takes one step toward a certain program, and the council takes the opposite step back.

City Council Speaker Christine Quinn and Finance Committee Chairman David Weprin have criticized this because it wastes time and accomplishes little. In 2006, both Weprin and the speaker claimed the council had done its last dance. The mayor seemed to acknowledge that last week when he told agency heads that he expected them to suggest genuine savings and not a plan that "takes the most politically popular program and closes it."

That statement aside, the dance already seems to have re-emerged. "It was kind of a back to the future," said Turetsky of the mayor's budget. "Where you had some of the same old litany of cuts to summer jobs, library subsidy, seniors services. ... It seems that they are playing the same tune."

The new fiscal reality could change the tune, Weprin said. "It's a little different. We know we have to do a billion dollars in cuts," he said. Despite that, Weprin said, the council probably would come to the rescue of some of its favorite programs, like libraries and senior and children's programs.

Snipping Away

While the mayor did not list precise cuts, some programs teeter on the chopping block.

The 5 percent cut in libraries threatens the effort to have all libraries open six days a week, which was included in last year's budget.

The Department of Sanitation may eliminate leaf collection, which runs for four weeks in the fall in the outer boroughs and costs the city $2.25 million. The department also proposed dropping some supplemental collection in the outer boroughs.

Some single adult homeless shelters are slated to shut, which will save the city approximately $2.5 million. The closures, said a Department of Homeless Services spokesperson, are in response to a decline in the number of homeless single adults. The department's entire financial plan for fiscal 2009 is slated for a 15 percent decrease, primarily because it does not include funding for the increase in homeless families that occurred in fiscal year 2008. In an emailed statement, a department spokesperson said the decrease would be possible because of shorter stays at shelters and efforts to move people back into the community. "As always, DHS's budget is adjusted year-to-year to ensure we continue to serve every family and individual who is eligible for services at any given time," the statement continued.

Other efforts that might see a decrease in funding are senior centers, Meals on Wheels and summer youth programs.

On the other hand, some departments plan to increase revenues. The Parks and Recreation Department hopes people will pay to put their names on public facilities. The program would involve about four facilities -- probably swimming pools or tennis courts within larger parks -- with naming rights going for approximately $750,000 each. The rights would most likely be available to people not corporations. The department is also looking into holding more concerts at in the parks to boost revenue.

However the departments manage to balance their book, some advocates said they would not harbor any hard feelings, partly because the cuts are across the board. "We can't say that it is unfair," said Randall Bourscheidt, president of the Alliance for the Arts. "It would be hard for people in the arts to feel like they have been singled out."

Making the Grade

What is bound to cause some controversy is the proposed cut to the Department of Education.

During his time in office, Bloomberg has increased spending on education by about $4.5 billion. The funding for the Department of Education got an extra boost last year when the state finally settled the lawsuit on school funding brought by the Campaign for Fiscal Equity by pledging to give the city an additional $3.2 billion in education aid over the four years starting in fiscal year 2008.

Photo (cc) 2007, Runs with Scissors / Ken Stein.

The Department of Education is expected to spend about $20 billion this year on operating costs, including personnel, pensions and debt service. The mayor's preliminary budget calls for about $325 million in program cuts. It remains unclear exactly where these cuts will come - the Campaign for Fiscal Equity said it is still analyzing the plan. The budget does call for making the food program more efficient by requiring kids not eligible for free meals to pay for their lunch and for greater efficiency in purchasing and in using technology.

Individual principals, who have been given more control over spending at their schools, will see their budgets cut by an average of about $100,000 each, Schools Chancellor Joel Klein told the New York Times. As a result, he said, they will "have to tighten some programs," such as weekend tutoring or after-school programs. "My theory is that they should have some discretion," Klein added.

School cuts almost always attract opposition, though Bloomberg's record of increasing funding and focusing so much attention on schools may work to his advantage. "Everyone knows how important education is to him," the vice chancellor of the state Board of Regents, Merryl Tisch, told the Sun. "So if the mayor is recommending these cuts, you could be sure that he's not recommending them without having thought this through very carefully."

Some of the cuts may even please certain education advocates. The budget scales back the number of standardized tests, which the Klein has sharply increased over the years. "If that's the kind of stuff they're going to cut out of the education budget, count me in," wrote Reality Based Educator.

The State Adds A Little Less

The city schools could face further cutbacks if Gov. Eliot Spitzer's proposed budget becomes reality. Under last year's plan to settle the Campaign for Fiscal Equity suit, the city expected an increase of $530 million in state aid for school operating costs. Now Spitzer has proposed an aid increase, but of about $100 million less than anticipated.

Education advocates last week assailed the governor for reneging on the deal. "More than a generation of public school students in New York have already suffered delays that continue to affect their ability to compete in the global economy and actively participate as citizens," Geri Palast, executive director of the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, said in a statement. And city teachers union president Randi Weingarten said the union "look[s] to the legislature to restore these funds in order to maintain the integrity of the Campaign for Fiscal Equity agreement."

Education advocates are particularly dismayed at the $193 million reduction in so-called Foundation Aid to the city. This money comes with strings attached: In other words, the state - not Bloomberg and Klein - set limits on how it can be spent. The restrictions came out of an ongoing debate about whether the state should hold the city accountable for how it spends state education dollars.

With fewer restrictions on spending of state aid, Leonie Haimson of Class Size Matters, an advocacy group, has written, "the city could instead spend it on more testing, cash rewards tied to test scores, more consultants, higher salaries at Tweed, or really any new fad that strikes their fancy."

The state would also delay payment for new school buildings by about 18 months, which, according to the New York Times, would have a disproportionate effect on the city.

Looking to the State

City officials have vowed they will lobby the state for changes in the budget - on education and other issues - but, like the city, the state faces a difficult budget picture. Spitzer, unlike Bloomberg, set out some major new spending initiatives in his proposal for the fiscal year. Despite that, the $124.3 billion plan calls for less growth - slightly more than 5 percent - in spending than any budget in a decade. Some of the key increases come in money for upstate revitalization and programs for the state university system.

To fund that increase in these shaky economic times - and to avoid raising taxes - the governor looks to some unorthodox revenue sources, including a hefty hike in the tax on malt liquor, "monetizing" the state lottery and collecting taxes on cocaine sales.

Some critics questioned whether Spitzer's projections were too rosy. He even called it "a good news budget." But the governor noted that 20 percent of the state's tax revenues come from Wall Street, making some fear tougher times ahead. "They face coming back for a mid-year correction," Elizabeth Lynam of the Citizens Budget Commission told the Albany Times Union.