Our Small Business Crisis is Very Real, and Demands City Action

(photo: @shootingbrooklyn)

As a small business owner in New York City for 11 years, I believe it is imperative that city officials reframe the current debate over whether or not we face a small business crisis. In an August column for Gotham Gazette, Carol Kellermann used the results of a recently-published New York City Department of City Planning report on storefront vacancies as well as observations of her Upper West Side neighborhood to assert two conclusions: there is no citywide small business crisis and therefore the City Council should not enact citywide legislation to address a problem found in a small number of neighborhoods.

But the City Planning report data does show great struggle for small businesses and both the column and the report fail to capture the link among vacancies, small business closures, and the loss of neighborhood vitality and affordability.

The report pulls data from a nine-month average between 2017 and 2018 in 24 shopping corridors and uses an “industry standard healthy vacancy rate” of 5-10% as its benchmark. Putting aside the question of whether or not that is the best benchmark, the report found that 15 of 24 corridors studied - a majority - had vacancy rates above 10%. Across these 15 corridors, the average vacancy rate was 14.94%.

The question then should not be what number of high vacancy corridors constitutes a crisis but what do small business closures and high vacancies mean for neighborhoods and New Yorkers seeking work?

If for a case study we look at Williamsburg, one of the 24 retail corridors studied and with a reported vacancy rate of 16.6%, we can find two important answers: one, vacancies can mean a decline in access to useful goods and services that serve the neighborhood’s interests and means; and two, vacancies can mean a loss in high quality service and retail jobs.

To the first point, I closed my successful kitchenware shop in Williamsburg this April because my landlords demanded a 44% rent increase in order to renew for only five years (with 3% annual escalations). At the end of my 10-year lease I was already paying $18,452 per month for my 1,450 square feet. And I could afford to pay that because we had many loyal customers. We were not suffering from online retailers.

I would have paid $20,000 per month to stay, arguably a high rent, but the landlord demanded $26,500. The space has now been divided into three retail units, two of which are occupied. The largest is a ‘modern wellness’ business that offers whole body cryo and an oxygen bar. Whereas you could come to my kitchen shop and spend as little as $24 on a frying pan for daily cooking, now you can purchase a 3-minute cryo session for $75.

Across the street, private equity owned, luxury beauty brand NK Space Apothecary moved in. Sephora, Apple, Whole Foods, Citibank, Duane Reade, Equinox, Levi’s, G Star Raw, to name but a few major chains, now occupy prime retail in Williamsburg.

There is nothing wrong with any of these businesses. The problem is when too many businesses in a neighborhood are like these; when access to useful services and goods diminishes because they are replaced by too many luxury brands, too many duplicative services, and too many uninviting chains. A non-stop refrain from upset customers in our final days was that they “didn’t like their neighborhood any longer”.

Neighborhoods are ecosystems in which residents and services interact in an ongoing exchange of trades. But when trades diminish because fewer affordable and necessary goods are available, the ecosystem weakens. That fragility is exemplified by buyers turning more to online shopping (with all its attendant waste and pollution) and by residents being priced out of their neighborhoods.

To the point that vacancies can mean a loss in high-quality service and retail jobs, when I closed Whisk, seven staff lost their jobs and several are still seeking stable employment. Kellermann cites the loss of a beloved diner in her neighborhood which then sat vacant for two years. That two years represents meaningful unemployment for our neighbors, friends, and maybe family. It’s also about the quality of small business jobs. By virtue of being small, we can apply a sales associate’s talent for photography, numbers analysis, or web design to the business in ways that chains simply can’t.

Kellermann concludes that rents will come down so we don’t need citywide legislation now. Rents have softened in select areas but being down does not equal affordable. If a 1,000-square-foot space drops from $350 per square foot to $300 per square foot, it is still $25,000 per month. How many retailers or bars generate revenues to afford that? Not many. Moreover, small businesses are usually designed to provide a particular service in a particular neighborhood. They cannot simply pick up, finance a relocation to a new corridor or even side street, and recreate that market.

Citywide policy is absolutely needed to reframe this debate. Imagine how different Williamsburg would be in 2019 if we had had a zoning purview to limit chain retail; if we had been bold enough to talk about commercial rent stabilization; if we had mandated mitigation measures to protect against commercial and residential displacement?

Cities like San Francisco and London are having these conversations. New York absolutely needs to get ahead of understanding what vacancies mean for our neighborhoods.

***

Natasha Amott is the owner of Whisk, in downtown Brooklyn. On Twitter @Natasha_Amott.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Sentenced to Death by Incarceration in New York State Prison

Eastern Correctional (photo: wikimedia commons)

The conversation around criminal justice reform is finally moving from general talk about mass incarceration to the specific reality of the multitude of people serving massive sentences. The more accurate description of these sentences – death by incarceration – is replacing antiseptic phrases like “life without parole.” These long-term sentences are, in truth, sentences to death in prison.

Several years ago, the Defenders Clinic at CUNY Law School began working with people serving death in prison sentences on their only path to freedom: gubernatorial clemency. While we have worked with only a small fraction of the nearly 9,000 people serving life sentences in New York, it is enough to reveal the criminal legal system’s obsession with processing, convicting, and punishing.

Virtually everyone we have worked with was convicted after a trial, the case for most people serving life sentences in New York. This raises two questions: why weren’t those cases resolved through plea negotiations like virtually all other criminal cases, and what was the justification for meting out massive sentences on people who exercised their constitutional right to trial?

In several cases, we heard from clients that the defense lawyer never mentioned any plea offer. In many others, we heard about plea offers being superficially conveyed but virtually no time spent having the difficult yet crucial discussion of the pros and cons of a plea versus a trial. We repeatedly heard about a complete lack of advice from the attorney about the wisdom of accepting or rejecting a plea offer.

It became clear from conversations with lifers that many of their assigned lawyers had been eager to take cases to trial and forgo the serious consideration of a plea, especially since most were being paid an hourly rate by the court and had a financial incentive to take a case to trial regardless of the risks to their clients.

Almost all the people we worked with were represented by a lawyer assigned by the court. They had no say in who their lawyer was and had no realistic way of replacing that lawyer (and many tried). Over and over we heard the same thing: ‘my lawyer did not come to the jail to meet with me a single time while my charges were pending.’

We also learned that the failures of many of these attorneys did not end with the lack of client counseling. Considering the enormous sentences handed down after trial, perhaps the lawyers’ greatest deficiency was at the sentencing proceeding itself. In most cases, there was no pre-sentence memorandum supporting an argument for a lesser sentence and no mitigation advocacy of any kind.

In several cases, sentencing advocacy consisted of a few generic sentences from counsel asking the court to be lenient. In one case, there were serious pretrial issues regarding the accused’s mental capacity, but at sentencing the defense counsel said nothing about his client’s documented history of mental illness.

It would be a grievous mistake to blame defense counsel for all the ills that define the criminal legal system. After trial, prosecutors routinely asked judges to impose the maximum sentence and judges were glad to oblige, often tacking on consecutive sentences to ensure that the person would die in prison -- and to send a loud message to anyone else who had the temerity to insist on the right to a trial.

One man was offered a plea of three to nine years, went to trial, and is currently serving 25 to life. Another was offered 25 to life pre-trial yet sentenced after trial to 125 to life. Some argue that plea offers are a discount and a necessary ingredient of the adjudication of criminal cases in an imperfect system. However, such disparate outcomes – 25 to life if you plead, 125 to life after trial – cannot be justified.

As we spent more time with those serving life sentences, we saw the impact of a merciless and punitive system in countless ways.

Many lifers are from rapidly gentrifying parts of New York City. Most were sentenced in the 1980s. They are black and Latinx. A majority are from places like Bedford-Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, and the Lower East Side. Their families were long ago priced out of the neighborhood as long-neglected zip codes have changed so drastically that the lifers would barely recognize where they grew up.

In New York, there are 613 lifers who were 17 and under at the time of their charges. There are thousands more convicted when they were 18, 19 or in their early twenties. Many are now in their forties and fifties having served decades in prison for crimes committed in their youth when labels like “super-predator” fed into racist narratives and massive sentences.

Yet neuroscience now informs us that brain development continues into our mid-twenties. Even the Supreme Court now recognizes that youth have an underdeveloped sense of responsibility, are less culpable than adults, and have a greater capacity for rehabilitation. A growing number of states have passed laws that give young offenders an opportunity to seek parole or a sentence reduction after having served a proscribed number of years in prison. There is no similar movement afoot in New York to correct those morally indefensible, and arguably illegal, sentences.

There is a rapidly growing aging population in New York prisons. These people have long since aged out of any real possibility of future criminal behavior. Many are dying. New York has a mechanism in place for compassionate release for those with terminal illness but from 2013-2017 only 72 people were granted medical release.

Many law students came to this work inspired by Innocence Projects across the country. We have worked with several people with undeniable innocence claims that have fallen on deaf prosecutorial and judicial ears. But while the students wanted to join the battle for justice for the wrongly convicted, they soon discovered a much larger area of unjust convictions – the many lifers who, even if not factually innocent, were denied any semblance of due process.

One man’s lawyer, unbeknownst to him, had a pending lawsuit against New York City based on an incident where a client less than a year earlier slashed him with a razor during a visit in the holding cells. As part of that lawsuit, the lawyer testified that he was seeing a psychiatrist and had trouble relating to clients.

Another man’s lawyer, unbeknownst to him, was under investigation by the very same District Attorney’s office prosecuting him. The lawyer was indicted soon after the verdict (and ended up in state prison), and a new lawyer appeared at sentencing.

In another case, the defense claimed that a prosecution witness had been coerced into testifying falsely by the prosecutor. That prosecutor thereafter became a defense attorney and is now in federal prison for suborning perjury.

Another man is serving a life sentence based on a case where the lead detective turned out to be a serial murderer for the mob. The police file in the case is nowhere to be found.

In each of these cases, all appeals were fought by the prosecution and denied by the court.

Since we were working with people serving life sentences, many students assumed that these were people convicted of murder; people who had taken a human life. However, many of the lifers we’ve worked with were convicted of felony murder, a rule that allows a person to be charged with murder even if the death is at the hands of someone else. Several people did not kill anyone, fire any shots, possess a weapon, or have any intention, or even expectation, that anyone would be killed. Still, because they participated in an underlying robbery, they were convicted of felony murder and given a life sentence. Several of these men were teenagers at the time they were arrested. There is a growing movement for states to reconsider the felony murder rule, but New York is missing in action.

We have worked with only a small number of the people serving life sentences in New York, and an even smaller percentage of the 47,000 people in state prison. Nevertheless, we have found ample reason to fear that the impact of long overdue criminal justice reforms, trumpeted daily and endorsed by countless politicians, may be far less than hoped until the extant incarceratory system within which those changes operate is dismantled or radically overhauled.

Meanwhile, it is time to demand clemency for the countless number of people who merit that relief, and to create second-look mechanisms that require immediate review of the massive sentences that fed mass incarceration.

***

Steven Zeidman is a professor of law at CUNY School of Law and a former Public Defender. On Twitter @SteveZeidman.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

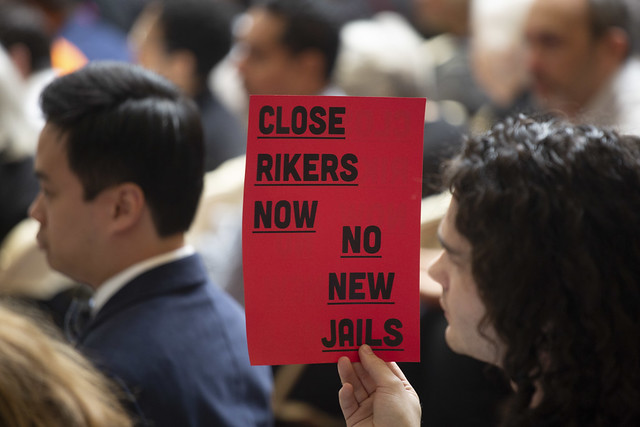

How to Close Rikers with No New Jails

(photo: John McCarten/City Council)

While not surprising from a political perspective given Mayor de Blasio's support for the plan, the City Planning Commission's recent vote to approve the very costly (about $9 billion current estimate) construction of new jails for the worthy purpose of closing the deeply inhumane facilities on Rikers Island was wrong and wrong-headed.

As the City Council now considers the four-jail plan, one in each borough but Staten Island, it should recognize that the city can take the much smarter and cheaper course: sufficiently reduce the overall jail population so it can close the Rikers jails and house the remaining imprisoned New Yorkers in the already-existing borough facilities, which have the capacity to hold about 3,000 people.

Here's how and why:

About 70% of the approximately 5,000 New Yorkers confined on Rikers are pre-trial detainees, presumed innocent under our system of justice, locked up mainly because an NYPD officer has arrested them and they are too poor to afford even the low bails set on them. The major bail reforms passed in Albany earlier this year will, as of January 2020, substantially limit the kinds of cases where judges can apply bail, thereby contributing to a significant reduction in the number of people remanded to Rikers.

None of the many sentenced people confined on Rikers have been convicted of serious offenses. If they had been, they would have been sent to a state prison. Many of them serve terms of 90 days or fewer. The city could readily find alternative ways to respond to most, if not all, of their cases.

Mayor de Blasio has rejected the blue-ribbon Lippman Commission's most important recommendation, which is to decriminalize four offenses: fare evasion, sex work, marijuana possession, and gravity knife possession (Albany did enact legislation in June legalizing the latter).

De Blasio backs NYPD "broken windows" policing, which targets and arrests low-income New Yorkers of color for petty infractions, sometimes via false arrests and bogus summonses, that police virtually ignore in white areas. Ending this starkly biased law enforcement tactic and following the Lippman Commission's proposal to decriminalize offenses above would contribute appreciably to reducing the population on Rikers.

In addition to ending "broken windows" practices, the city should jettison the NYPD quota system that puts pressure on officers to make a prescribed number of arrests and stops and to issue a certain number of summonses in order to earn positive job evaluations and to qualify for promotions and sought-after posts. While NYPD brass deny the existence of quotas—they are illegal, after all— a number of whistle-blowing officers have attested publicly (and privately to PROP representatives) about their use and the consequent harmful effects on cops and the community.

The Department is known, for example, to sanction officers who do not "make their numbers" by assigning them to precincts far from their homes -- dubbed "transportation therapy" -- or by denying them time off even for family emergencies.

The city could and should establish a task force accountable to City Hall that monitors court case processing. New York City's legal culture permits our courts to move much more slowly than other municipal systems in our country. The task force can, for instance, put pressure on judges to limit the number of court appearances per case as a way to prevent the longtime incarceration of detainees -- the tragic case of Kalief Browder comes to mind -- as they await disposition of the charges against them.

As city officials talk up new “modern” jails, the famous George Santayana quote is noteworthy here: "Those who don't remember the past are condemned to repeat it." I have worked on prison and related issues for nearly 50 years and cannot recall a single instance in history where promises that the new proposed facility will break the cycle of corruption and abuse that plague jails has become reality.

Opened in 1931, Attica was the most expensive prison in the world, advertised as being equipped with all available modern amenities and as being safe and humane. Similar claims were made regarding Rikers Island when the city opened jails there in the 1930s.

People now claiming that the proposed new jails, run by the same Department of Correction and personnel responsible for Rikers, will not feature the same harsh and perilous conditions of confinement as Rikers are drinking an age old Kool Aid -- some are engaged in pouring it.

Closing Rikers without spending billions of dollars on unneeded new jails —under this no new jails plan the city will have to allocate some funds to fix up, and improve conditions inside, its existing borough facilities—will not only remove from our great city's landscape the stain of operating notorious Rikers jails. It will also eliminate some of our police and criminal justice systems' abusive and discriminatory practices that inflict harm and hardship on vulnerable New Yorkers every day. Our city will be a better place for it -- more just, safe, and livable for all our people.

***

Bob Gangi is Director of the Police Reform Organizing Project. On Twitter @GangiFromPROP & @PROPNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.