I Was Andrew Yang’s First ‘Freedom Dividend’ Recipient - When He Fired Me

Andrew Yang (photo: @AndrewYang)

After the game show stunt that Andrew Yang pulled at the presidential primary debate last week, a lot of people have speculated that he should and will drop out of the race soon. But there is another reason why Andrew Yang doesn't belong on the national political stage, and it involves the reason that Yang fired me in 2007 and how my termination highlights the danger of his "freedom dividend" program.

Manhattan GMAT is a testing preparation company, founded in 2001, to help people get ready for the Graduate Management Admission Test, often used for business school programs, among others. I was its first employee and its primary revenue generator during the start-up years. I had been one of the first Manhattan GMAT teachers, so I knew the test really well, and in the early days, I spoke to every single student, every single customer.

I forged relationships with marketing partners. I created our advertising collaterals. I taped posters to bus stops on Broadway, and I gave out cookies to hungry young bankers at open houses. I even snuck postcards into our competitor's books at the bookstore to grow the company. As the Marketing and Student Services Director, I met all of my revenue marks. By 2005, we'd expanded to other cities and were a multi-million dollar operation.

Then, Andrew Yang became president of the company. He had taught a couple of classes over the years, so I knew him already, but he was not at all involved in the company's operations before then. He promoted me to Senior Director just after he started, and again, I hit all of my growth targets.

Imagine my surprise, then, that on the third day that I was back to work after my honeymoon in 2007, Andrew Yang fired me. Our private discussion, in his office with the door closed, began with Andrew's remarks that because I was married, I wouldn't want to continue working as hard as I had been. That as a wife, I'd be focused on my new life.

At-will employees are let go all the time. I could be fired at any time without a reason.

But Andrew did give me a reason. I didn't even realize at the time how unethical his reason was. I was singularly focused on the embarrassment I felt. How could he fire me after all that I had accomplished at the company. And the horror I felt knowing that I'd have to tell my new husband that our life was shattered (he made less than 15% what I did).

Andrew must have calculated that I would work less, travel less, put in fewer hours as a married woman, yet still earn my six-figure bonuses. He had seen how seamlessly my staff had performed while I was on my honeymoon. He probably thought that they would do the work cheaper. With my compensation package off the books, several college grads could be brought in to spread the work around. And just like that, my wedding and honeymoon had rendered me obsolete from the company that I had helped to build.

Since the termination was couched for me, as a "freedom to move on" narrative, the deal Andrew Yang offered me was commensurate with what he believed I deserved, a monthly payment for no longer working. For two years. I agreed in the end (part of a much longer story) to go away, to take the monthly payoff, which paved the way for the company to develop more sophisticated money-making initiatives at cheaper costs.

Sounds a lot like Yang’s "freedom dividend" platform doesn't it? Yang is basically telling the American public that the government will pay them off each month. Rather than governing our way into a sustainable economy, Yang's plan absolves the government from overseeing companies that could render countless workers obsolete. With a monthly payment, the under-educated, aging, perhaps newly married - the obsolete employees - recede into the background as trillion-dollar companies continue to grow unfettered and ungoverned as they have for decades.

Candidates for elected office must be scrutinized more. Past behavior is a predictor of future behavior. And behavior is a reflection of values. The values that it takes to shatter a successful woman's livelihood days after she marries is a deal-breaker for a presidential candidate. At least it should be for women. We have been suppressed, discriminated against, harassed, and abused for far too long, and often behind closed doors, where we are left to carry the burden of shame for actions carried out against us.

Even more importantly, Americans shouldn't take the carrot of a monthly payout without understanding what the deal really means. The “freedom dividend” means that workers are no longer believed to be valuable, that they can't learn new skills, develop new industries and adapt to an ever-evolving existence in our great country. What a depressing approach to the future!

The Democratic Party has a wide array of highly-qualified, committed public servants from which to choose. Andrew Yang is not one of them.

***

Kimberly Watkins is a running and fitness coach in Manhattan and serves as the President of the Community Education Council, in New York City Public School District 3 on the Upper West Side and Southern Harlem. On Twitter @kimwatkinsnyc.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The MTA Needs a Real Capital Plan, Not Unrealistic Promises

(photo: Don Pollard/Governor's Office)

On Monday, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) released an 11-page slideshow “overview” partially summarizing the details of its nearly $55 billion 2020-2024 capital plan. The unveiling seemed like Christmas morning - according to MTA CEO/Chair Pat Foye, the plan will sell itself. Everyone will get the pony that they asked for. NYCT President Andy Byford was “ecstatically happy” and elected officials and advocates were told they’d get their top priorities, ranging from costly expansion projects to new subway and commuter rail cars, buses, signals, and elevators.

Who wouldn’t want a huge infusion of funds into a century old, workworn transit system? We too want to believe! Unfortunately, the numbers just do not add up.

We question both the availability of the funding coming in and the ability of the MTA to spend this massive outlay. Historically, transit advocacy has centered on finding funds, but last year we started looking at actual expenses -- not “commitments” or authorizations to spend, as the MTA does. We found that the real constraint on MTA capital plans has become the ability to spend, not finding funding. (A related problem is keeping costs down so that what can be spent is done so efficiently.)

This plan is really Governor Cuomo’s. He controls the MTA, as described in great detail in our OpenMTA report. There are a few reasons we think his $55 billion “five-year” plan is not tethered to reality. While the Governor’s plan shows that he wants the MTA to spend 70% more on its 2020-2024, the MTA’s capacity to spend that much will not grow nearly as quickly.

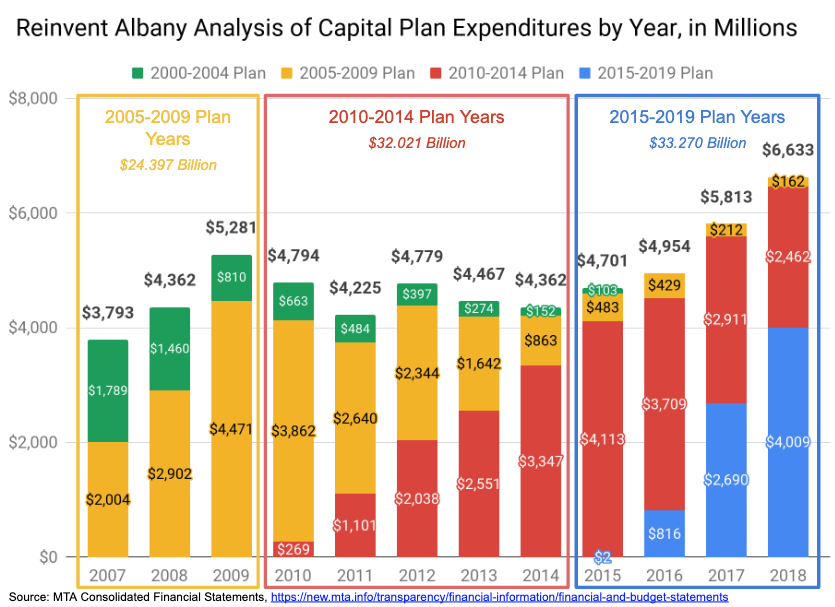

In 2018, the MTA spent a record $6.6 billion on capital projects. However, only $4 billion of that was for current projects -- the other $2.6 billion was to complete projects from previous plans.

For about two decades the MTA has gotten further and further behind spending its capital funding. As a result, there is a growing hangover of past-year projects that must be completed every year. We estimate there will be at least $20 billion worth of 2015-2019 projects for the MTA to finish during the 2020-2024 plan.

Let’s assume the MTA can keep capital spending at the record pace of $6.6 billion a year. If it finishes the 2015-2019 plan in five more years, spending an average of $4 billion of the $20 billion per year, it leaves only $2.6 billion a year for 2020-2024 projects. And wait, the MTA still hasn’t finished the 2005-2009 or 2010-2014 plans. Clearly, something is off here.

We believe that projects that will not be built for at least a decade are more aspirational than real. By promising everything to everyone, the Governor is actually making it impossible to know which projects are real and which are not.

Given what was released this week is still technically a draft (and we’ve still only seen an outline, not a full plan) that must be approved by the MTA Board and Capital Program Review Board (CPRB), there is still time for the MTA to release a real implementation plan showing how it intends to finish this new plan along with all its current projects.

How Much Can the MTA Really Spend On a Five-Year Plan During the Plan?

Bluntly, we think it will be difficult for the MTA to spend even half of the $55 billion proposed for the 2020-2024 plan during that five-year period. MTA capital plans often taking more than 10 years to be completed. While this is not a new challenge, a capital program of nearly $55 billion is unprecedented and presents a good opportunity to figure out how to fix this ongoing structural MTA problem.

The MTA’s ability to spend capital dollars during plan years has decreased, not increased. In 2018, the MTA spent $6.6 billion on capital projects, but only $4 billion was for 2015-2019 projects. The MTA’s best-ever year for spending on projects from the current capital plan was in 2009, when it spent nearly $4.5 billion (see chart below).

With the 2015-2019 plan’s late start in 2016, there is a lot of work still left to do on that plan. The 2015-2019 plan has $33 billion worth of projects, but the MTA has only received $12 billion in funds as of June 31 of this year, and as of the end of 2018, only $20 billion worth of projects were committed. (A commitment is not the same as actually spending the money, it is the intent to use employees to complete a project or execution of a contract).

Can the MTA effectively manage more than $6.6 billion a year total in capital spending?

Given the MTA’s limited spending capacity, questions about the credibility of delivering a nearly $55 billion capital plan are warranted. With the recently-approved MTA reorganization, consolidating capital construction staff to headquarters will mean that the MTA will have to do even more with even less. Whether centralization will indeed lead to meaningful efficiencies will take time to determine.

Even if we give the MTA the benefit of the doubt and it does as well as it has in the past, getting $4.5 billion out the door every year, it will take 12 years to finish the 2020-2024 plan. This is all while it has a lot more to do on the current, 2015-2019 plan.

Given the limited ability to manage projects, what will the MTA prioritize?

The slideshow proposes what would be the largest investment in signals for MTA New York City Transit ever, at $7.1 billion. This comes with other large investments for elevators and subway cars, all while large expansion projects are continuing, such as East Side Access and LIRR Third Track.

With limited spending and staff capacity, the MTA will have to choose which projects come first and which come last. Janno Lieber, the MTA’s head of capital construction, has said that signals will come in the five-year window, but as of now, the MTA has not released an implementation plan or detailed project list with schedules of when it will commit to projects, as it has shown in prior plans.

Revenue Dependent on New Federal, State and City Fundings

The nearly $55 billion plan outline makes a number of big assumptions about funding that has not yet been secured. New funding is supposed to come from the federal government ($10.7 billion), the state government ($3 billion), and city government ($3 billion), totalling nearly $17 billion. These numbers are not real until the cash actually arrives from all parties involved.

Is it realistic to expect $10 billion in federal aid?

Under a Democratic president, the federal government contributed $7 billion to the last capital plan. This plan assumes even more federal dollars will come in, including a large contribution for Second Avenue Subway Phase 2: $2.9 billion alone. The feds provided $1.3 billion for Phase 1, so this would double that contribution to this project. While the President indicated support for the project via Twitter, a tweet is not a funding commitment of $2.9 billion.

Is it realistic to expect the state to provide $3 billion in direct aid?

While Governor Cuomo has said the state will provide $3 billion to the new plan, this is subject to legislative approval. The proposal of the Mayor’s match of $3 billion is also under review. Meanwhile, the state still owes $7.3 billion to the MTA for the 2015-2019 plan: it had pledged $8.3 billion in 2016 and only $1 billion has come in so far.

State Comptroller Tom DiNapoli, in his recent report on the MTA’s finances, noted that the remaining $7.3 billion will not start to come in until next fiscal year (beginning April 2020). The state also may not provide this as direct aid. It could authorize the MTA to issue its own bonds based on existing or new revenue, meaning that the impact on the MTA and taxpayers is still unknown.

Debt Service and the Operating Budget Crisis

Beyond the MTA’s huge capital needs, it already doesn’t have enough money to pay for the costs of running the system everyday. This is due in large part to debt service payments on previous capital plans. Debt service payments eat up 17% of the MTA’s operating budget now, and the MTA faces even larger out-year deficits.

Even without new borrowing, the MTA forecasts that its debt will increase 31% by 2023 and will cost more than $3.5 billion a year. A hiring freeze and cuts to staff such as subway car cleaners have meant that MTA workforce morale is low, while customers are increasingly unhappy with the quality of service. And “service guideline” cuts are on the horizon for this fall.

Will riders endure even more cuts as a result of this plan?

The operating deficit is already significant, and the MTA’s 2020-2024 capital plan outline assumes the MTA will pay for part of the plan with $10 billion in new debt. How much this debt will increase the MTA’s debt service payments, and therefore its operating deficit has not yet been explained to the public. This information is needed to understand exactly what impact the capital plan will have on the MTA’s ability to actually deliver service for its riders, its primary objective.

Real Transparency is Honesty

Reinvent Albany and our colleagues last week announced the Build Trust campaign, asking the MTA to release an implementation plan to show exactly how it will deliver on its promises, and provided a blueprint for better transparency and cost control. To us, transparency is not merely about putting more data online, but presenting real, honest information to the public.

To comply with state law, the MTA will have to hold a vote on the complete draft capital plan at its September 25 board meeting. As soon as the MTA Board receives the actual capital plan, it is required to be put it online where the public can see it. Yet with less than a week remaining before a Board vote on the $55 billion spending plan, the MTA has not released two important things: (1) the “20 Years Needs Assessment” with a detailed analysis of how much money is needed to repair the system and (2) the full, detailed list of capital projects in the proposed capital plan, with a detailed implementation plan.

When will the MTA release its 20-year needs assessment and federal TAM plan?

In theory, the MTA is supposed to follow a logical process to determine how much it needs to spend restoring the transit system.

First, the MTA is supposed to compile an inventory of its equipment and infrastructure, including the condition of its assets, and then it is supposed to compile its needs assessment of how much it will cost to repair the system so it can provide good service.

The inventory of its equipment is part of a new federal requirement called the Transit Asset Management or “TAM” plan. The needs assessment has taken the form of a 20-year needs assessment, last released in October 2013 for the last plan. Neither of these documents is publicly available for the next plan.

Without a 20-year needs assessment, or the underlying data about its assets, the public cannot know how much the MTA should be spending to replace very old, but crucial, subway and rail components, like decades old mechanical switches, electrical systems, pumps and fans. (See Reinvent Albany’s report on the MTA capital plan process.)

Decisions on capital spending don’t have to be political - they should be based on real data that takes the subjectivity out of the process.

When will the MTA release its full capital plan, with an implementation plan?

The MTA’s 11-page slideshow does not differentiate between “core” repairs versus expansion projects, lumps together costs over multiple plans, omits large capital projects, and provides no implementation schedules. This is troublesome and again raises questions about the MTA’s commitment to public transparency.

Project lists from prior capital plans have tallied more than 60 pages, itemized and coded by type of project. This allows the public to see exactly how the plan breaks out, such as how many fixes to broken equipment there are versus spending that may be more cosmetic, like the last plan’s Enhanced Station Initiative.

Expansion projects are usually expensive, representing an opportunity cost for fixes that don’t involve ribbon cuttings but are crucial like new power stations needed to run additional trains.

These lists have also included project commitment schedules, showing when the MTA intends to commit to projects (again, not spend) during the five-year window. This is the basis for developing a real implementation plan, and should be expanded upon by the MTA as recommended by the Build Trust campaign.

Before the new MTA capital plan is final, the public and stakeholders like the State Legislature -- which should hold hearings this fall before the plan is approved by the CPRB -- need a lot more detail than 11 pages to fully buy in. It is the public’s money after all, and members of the public deserve to be treated like investors who have been given a real, honest plan before staking their own money on the MTA’s future.

***

Rachael Fauss and John Kaehny are, respectively, senior research analyst and executive director of Reinvent Albany. On Twitter @ReinventAlbany.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

An Unsigned Piece of New York’s Decarceration Puzzle

(photo: the governor's office)

Where is Assembly Bill 6980? It updates New York’s Charitable Bail Fund Act to allow approved organizations to bond more people out of jail. The bill passed the Assembly on June 17 and the Senate on June 19, but it hasn’t been sent to Governor Andrew Cuomo, or requested by the governor for his signature, and it’s not clear why.

Bail reform activists finally had their day this year when the New York Legislature passed a comprehensive law that more than overhauled -- it essentially overturned -- the state’s money bail system. It didn’t eliminate the way people pay cash for freedom when they’re legally innocent, but it came close. Of the almost 205,000 criminal cases arraigned in New York City in 2018, only 10 percent of defendants would have needed money for bail if the new law had been in effect.

The new law wasn’t enough for some, though. Carl Heastie, the speaker of the Assembly, admitted that the bail reform law “didn’t go as far as we had liked.”

And that’s exactly why Assembly Bill 6980’s stall-out is both puzzling and problematic. A full and fair reform of the state’s money bail system can’t be realized without it being codified, which members of the Legislature recognized by passing it in June.

Even with the new bail reform law in effect, approximately 20,000 people in New York City alone stand to have their lives uprooted if they’re picked up by police, arrested and subjected to monetary release requirements. Thousands more outside the city face the same risk.

If a judge decides to set a monetary bail amount over $2,000 for a defendant charged with a felony, that person lands in the same situation as before: if he can’t afford to bond out, his freedom will be snatched from him when he’s still presumed innocent and while he can best help his attorneys with a defense. Currently, no bail bond fund can touch him; the law caps the allowable amount at $2,000 and limits assistance to those charged only with misdemeanors.

Assembly Bill 6890 will help fix that. It raises the amount that a charitable bail fund can post to $10,000 and imposes no restrictions on the nature of the charges of the beneficiary of the bail fund, the person who gets bonded out.

Charitable bail funds aren’t new. The first in New York, Bronx Freedom Fund, started in 2008. But it was far from welcomed; a judge sought to shut it down, saying it was illegal. But because it addressed a real need in a state that couldn’t solve the problem of a pretrial detention system that disproportionately pens poor people of color, New York State licensed charitable bail funds in 2012 through the Charitable Bail Fund Act, the law that currently constrains their ability to more fully do what they’re designed to do.

New York City started its own bail fund in 2017 -- the Liberty Fund -- precisely because the city doesn’t control state law, and uprooting the monetized scheme that we call pretrial release wasn’t something the city could accomplish on its own. Charitable bail funds are safety valves when the law doesn’t provide sufficient justice.

It would seem like New York bail funds will have limited utility after the bail reform package goes into effect on January 1, 2020. After all, if money isn’t an issue for 90% of the arrested population, then what can these organizations do?

The short answer is: a lot. In New York City alone, only 43 percent of the almost 5,000 pretrial detainees on April 1, 2019 would have been released under the new legislation. That means that 57% of detainees may remain in custody, even under this revolutionary reform. A study from the Center for Court Innovation found that almost half of all defendants were incapable of paying their bonds immediately after arraignment.

And the likelihood that they will plead guilty, even to crimes they didn’t commit, is about four times higher than if they were kept from confinement while they’re prosecuted. Pretrial release increases the chance that a defendant will be found guilty by about 14.8%. The fact that people enter guilty pleas simply to get out of custody accounts for much of that increase.

While a good number of these people will benefit from and be freed by the new reform law, failing to send this revision of the Charitable Bail Fund Act on to the governor for the final step suggests that lawmakers might have a tad too much confidence in their accomplishments.

Several states have proven that things don’t go exactly as planned when they try to jettison money bail. In California, the bail reform statute never reached fruition even though it was signed by the governor; opposition to SB 10 prevented its implementation.

Even when legislative efforts succeed and laws go into effect, the results can fail. In Illinois, Cook County Chief Judge Timothy C. Evans implemented new rules designed to stop judges from setting unaffordable bond amounts. Initially, it looked like the new rules were working, until judges started setting bonds in untenable numbers to keep people they deemed dangerous incarcerated during the pendency of their cases. The dollar of money baiI set in 30% of cases in Cook County was unaffordable. In Maryland, the system overhaul backfired and ended up causing more people to be remanded to custody than before.

New York legislators had the advantage of knowing about these miscarriages as they drafted their bail reform bill, so they sidestepped many potential pitfalls. They had on their side the fact that New York is the only state to prohibit judges from considering a defendant’s alleged dangerousness in deciding pretrial release conditions. And, luckily, judges in New York City had unofficially decided to lean more towards releasing the people appearing before them prior to the bill’s passage.

But they can’t ignore the opposition to the new bail law that exists and the unfortunate reality that judges will do what they please. If reform does go haywire in New York, poor defendants need a back-up plan. A necessary part of that plan is charitable bail funds being able to fulfill their mission.

The New York Assembly should send 6980 over to Governor Cuomo post-haste.

***

Chandra Bozelko writes The Outlaw column for GateHouse Media and was a 2018 Pretrial Justice Innovator with the Pretrial Justice Institute.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.