The Small Business ‘Crisis’ That Isn’t

(photo: William Alatriste/City Council)

When shops and restaurants that you love and depend on close it can be heartbreaking; I know from personal experience. My Upper West Side neighborhood has been seen as the epicenter of what some call a “small business crisis” in New York City, and we have certainly seen our share of lost community icons and long-shuttered storefronts, but a new report shows there is no citywide crisis and lawmakers should be very careful as they consider remedies to what problems do exist.

Earlier this month the New York City Department of City Planning issued a comprehensive, well-designed study of vacancies on commercial business strips in 24 neighborhoods across the city. It shows that retail storefront vacancies are not unusually high in most neighborhoods (the industry standard is 5-10%) and, where they do exist, are due to a number of causes, which differ from place to place and storefront to storefront.

Just last month, a package of bills was adopted by the City Council that will provide even more information about retail vacancies by requiring that landlords report periodically to the Department of Finance on the number and status of their retail spaces.

Yet elected officials continue to refer to a “crisis” of retail vacancies. Just a few days after the City Planning report was released, Council Speaker Corey Johnson bemoaned the “blight” of retail vacancies “all across the city.”

Examples of long-standing merchants priced out by rising rents are more compelling news stories than data that shows the localized nature of the problem. So, despite the fact there is no citywide crisis and the Council’s new legislation will provide additional data on vacant storefronts, support is strong for a proposal to require sweeping protections for retail tenants to help assure lease renewals, including mandatory 10-year terms and arbitration when landlord and tenant cannot agree on rent increases. The number of Council sponsors of the “Small Business Justice and Stability Act” (SBJSA) has grown to 30 (of 51 members) since a hearing was held on it this past December.

Concern about retail storefront vacancies and turnover in New York City is not new. It has been labeled as a “crisis” as far back as the 1970s and was a focus of intense scrutiny during the Koch administration in the mid-’80s when the mayor responded by forming a commission to study the topic. Then-Manhattan Borough President Ruth Messinger championed a rent arbitration proposal back then.

Several of my favorite restaurants, diners, and clothing stores on the three blocks of Amsterdam closest to my apartment have closed over the last ten years. There are many vacancies in my neighborhood for a number of reasons.

Some are due to the creation of new, unrented retail space on the ground floor of brand new high-end residential buildings that have sprouted up along the corridors; some are because proprietors decided to retire, or because a new enterprise misjudged how much business it would attract in the area, or because the landlord -- sometimes a residential rental or co-op building -- is holding out for a chain store type of tenant that can pay a high rent to help offset increasing costs like property taxes. This is all part of life in an upscale neighborhood like the Upper West Side. It may be unsettling and even sad, but it is not a crisis.

Also, while some of us may miss our favorite places, the new stores and restaurants that replace them are serving the people that live here, albeit in different ways.

An example is a large new restaurant/juice bar that has opened around the corner from my apartment. A beloved diner used to be there, and when the lease was not renewed nine years ago, it remained vacant for more than two years. The two small stores next to it were also vacated, while the rental apartment building owner held out for a larger tenant to take over the entire space. A slick new place arrived that lasted five years but didn’t seem to me to have been able to generate enough business to sustain the large space. (There were protests when the spaces were combined and when the new restaurant opened.) After another six months, Tacombi, which has several other branches in the city, opened. With a menu of reasonably-priced Latin-American food and drinks it appears to be thriving and is filled with neighborhood families.

It is understandable that elected officials feel compelled to “do something” when their constituents feel impacted in such a direct and personal way, which explains why my City Council representative, Helen Rosenthal, along with Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, are two of the most vocal advocates for the SBJSA. But as the City Planning report shows, there is simply no basis for citywide legislation. Time will tell, but I expect that the newly-mandated reports from landlords will bear out that conclusion.

Moreover, the SBJSA will do nothing to bring back beloved stores that have already closed and could make it even harder to bring in new tenants since landlords, with less flexibility to respond to the market, will be more selective and want only those with a proven record of financial viability.

A more targeted approach would focus on strengthening retail storefront presence in those areas that City Planning calls “Underperforming Corridors” – in Coney Island, Brownsville, Richmond Hill, and Longwood -- which suffer from long-term historic disinvestment. Incentives and/or modest tenant protections would help these areas without interfering with business decisions in high-income areas that don’t need help.

We are not suffering from a shortage of places to shop or eat on the Upper West Side. The market will work here: if stores remain vacant for too long, landlords will lower the rents. That appears to be starting to happen.

The Council should not forge ahead with sweeping legislation that will impose real burdens on landlords in the majority of neighborhoods.

***

Carol Kellermann was president of Citizens Budget Commission from 2008 through 2018.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

State Campaign Finance Commission is About to Get to Work; Here’s How It Can Help Albany Clean Up Its Act

(photo: governor's office)

Over the next few months, New York State is poised to overhaul its campaign finance laws in ways that will help reduce corruption and pay-to-play and give more of a voice to the average person.

The potential for this major reform hinges on the actions of the Public Financing and Elections Commission. It is no exaggeration to say that the commission can achieve historic change when it issues binding recommendations on December 1.

The Commission was established during the April budget deal following a campaign for public financing by the 200-group coalition Fair Elections for New York, including Reinvent Albany. The nine-member state commission was appointed by Governor Cuomo and legislative leaders, and is charged with establishing a public financing program.

We want the commission to create a strong small-donor matching program, dramatically lower campaign contribution limits, and establish independent enforcement as in New York City’s successful program, which is widely seen as a national model.

A public financing system encourages everyday New Yorkers to participate in our democracy by matching small contributions (or a small portion of a contribution) with public funds. This amplifies the voice of regular folks who cannot make large contributions, and often aren’t even asked for donations.

Reinvent Albany found the state’s legislative leaders raised few campaign donations from the very people they were elected to represent during the 2018 election cycle. State Senate leaders raised only 23 percent of their contributions from their home district residents, while Assembly leadership raised just 16 percent.

Public financing is essential for fixing our broken campaign finance system. Most of the money donated to Albany elected officials comes from special interests – corporations, associations, and unions – and very wealthy individuals. The 2013 Moreland Commission found the Assembly Health and Senate Committee Chairs in 2011-2012 received about three quarters of their campaign contributions from lobbyists or the healthcare and insurance industries. Candidates received 65% of their funds from donors who gave $1,000 or more and just 3% from donations of under $100 during the same period.

If this year’s commission truly wants to change Albany, it must establish a strong public financing system. Reinvent Albany has put forth 18 recommendations for a strong public financing program, including these critical components:

-Create an independent agency to administer campaign finance for all candidates, including those who take public funds. With the state giving public funds for campaigns, the enforcement agency must be fair, independent, and safeguard taxpayer funds so they are used appropriately.

-Dramatically lower contributions limits – and make even lower limits on doing business donors – for all candidates. Candidates must be incentivized to participate in the voluntary public financing program rather than opt out and accept large donations. Donations to all candidates must be low enough so they do not create the appearance or reality of corruption or pay-to-play.

-Set reasonable thresholds to receive public funds. Candidates only receive public funds if they show community support measured by the number of small contributions and the dollar amount raised. These figures must be low enough so community members with local support can run for office.

-Match small contributions only. Only small contributions should be matched with public funds. A common misconception of the New York City public financing program is that candidates are given $6 in taxpayer funds for every $1 in small contributions up to $175. The truth is the first $175 of any contribution, no matter the size, is matched $6 to $1. Reinvent Albany believes taxpayers should not subsidize large contributions – currently allowed up to $70,000 – under New York State campaign finance law.

-Establish “sure winner” restrictions. To protect public dollars and the integrity of the public financing program, public funds should not be given in full to candidates with nominal opposition. Only a portion of public funds should go to candidates whose opponent has few endorsements, little media exposure, or hasn’t held an elected office previously.

If the Public Financing Commission includes these components in its program, and applies it to all offices and elections, New York’s campaign finance system will stand as a national model for addressing the problem of money in politics.

The commission and its appointers – the state’s leaders – should seize the moment for, at long last, transformative change.

***

Alex Camarda is Senior Policy Advisor at Reinvent Albany. On Twitter @alex_camarda & @ReinventAlbany.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York City Further Dominates State Job Growth; Rest of State Still Growing Slowly

(photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

New York City is now utterly dominating job growth in the State of New York. In the past two-and-a-half years, 79% of all new jobs in the state have been created in New York City.

New York State Labor Department seasonally-adjusted data show that 230,000 of the nearly 293,000 jobs created in the state from December 2016 to June 2019 were in the city. The growth rate in the city for the two-and-a-half year period was 2.1% per year; for the rest of the state separate from the city, the growth rate was about one-half of one percent per year*.

The city's share of growth has picked up even more since the end of 2017; 138,000 of the 169,000 jobs created statewide from December 2017 to June 2019 were created in the city -- nearly 82%. The city's share of total state employment was 46.5% at the end of 2016; as of June 2019 its share was 47.5%.

In October 2018 I wrote about the increasing contribution of the New York City economy to the state's tax revenue, much of it due to its share of employment growth. The increasing share of jobs will only accelerate this trend. While the city economy has become the engine of the state's economic growth, the Cuomo administration has focused much of its attention to rescuing the Upstate New York economy, which faltered in the two recessions that occurred after 2000.

|

NEW YORK EMPLOYMENT (000) |

||||||

|

Dec.2010 |

Dec.2016 |

June.2019 |

||||

|

New York State |

8587.4 |

9493.6 |

9786.2 |

|||

|

New York City |

3781.1 |

4413.6 |

4643.9 |

|||

|

Source: NY State Labor Department Seasonally Adjusted Employment |

||||||

Job growth rates for both New York City and the rest of the state have slowed compared to the period between December 2010 and December 2016. The city gained 633,000 jobs in that six-year period and its growth rate was 2.8% per year, compared to 2.1% per year since December 2016. The rest of the state gained 274,000 jobs in those six years, a growth rate of just under 1% per year. The city was 70% of the state's job growth in those six years, quite dominant then, but its share of growth just keeps expanding. Comparable national job growth rates for December 2010 to December 2016 was 1.9% per year, and 1.6% from December 2016 to June 2019.

One reason for slower growth outside the city is that job growth rates in the New York City suburbs have fallen to about the same rates of growth as Upstate. Upstate New York is a big area and one should not generalize too much about it. The growth rates in Upstate New York vary greatly by metropolitan area; some areas are achieving modest growth, others hardly any growth at all nine years after the Great Recession ended.

Long Island gained about 100,000 jobs from December 2010 to December 2016, but just 19,000 jobs in the past two-and-a-half years. The Orange-Rockland-Westchester metropolitan area gained 50,000 jobs in the 2010-2016 period, but just 7,000 from the end of 2016 to this June. These two New York City suburban areas had their growth rates slow from 1.3-1.4% per year from 2010-2016, to under six-tenths of one percent per year in the past two-and-a-half years.

One of their possible challenges may be the competition from New York City itself, since the city has become such a powerful economic and social magnet and these suburban areas are right nearby.

|

SUBURBAN EMPLOYMENT(000) |

|||||

|

Dec.2010 |

Dec.2016 |

June.2019 |

|||

|

Nassau-Suffolk |

1237.6 |

1338 |

1356.9 |

||

|

Orange-Rockland-Westchester |

663.7 |

713.9 |

724.3 |

||

The four larger Upstate metropolitan areas are growing. The Syracuse metropolitan area has gained more than 9,000 jobs in the past two-and-a-half years, growing at a rate of 1.2% per year. The Buffalo-Niagara Falls area has gained 10,500 jobs since December 2016, for a growth rate of three-fourths of one percent per year. From 2010 to 2016, it gained 20,000 jobs, for a growth rate of six-tenths of one percent per year.

The Rochester area gained 7,300 jobs in the past two-and-a-half years, a growth rate of .55 of one percent per year. From 2010 to 2016, it had gained about 23,000 jobs and had a growth rate of .8 of one percent a year. The Albany-Schenectady-Troy area gained 7,700 jobs since the end of 2016, for a growth rate of .7 of one percent a year. It had done better in the 2010-2016 period, gaining nearly 34,000 jobs in those six years for a growth rate of 1.3% per year.

|

UPSTATE LARGE METRO AREAS (000) |

|||||

|

Dec.2010 |

Dec.2016 |

June.2019 |

|||

|

Buffalo-Niagara Falls |

537.9 |

558 |

568.5 |

||

|

Rochester |

509.9 |

533.1 |

540.4 |

||

|

Albany-Schenectady-Troy |

432.7 |

466.5 |

474.2 |

||

|

Syracuse |

308.9 |

316.8 |

326.1 |

||

Several other Upstate metropolitan areas are growing at more than 1 percent a year. The Ithaca metro area had the best sustained growth since 2010 in Upstate New York, gaining more than 7,000 jobs, including 2,600 since the end of 2016, for a sustained growth rate for the eight-and-a-half years of about 1.5% per year. Two Hudson Valley areas, Dutchess-Putnam and Kingston, have gained about 5,700 jobs over the past two-and-a-half years for a growth rate of 1.1% per year. They have gained 13,000 jobs since December 2010.

Five smaller Upstate metro areas are struggling. Binghamton, Utica-Rome, and Elmira have gained 2,200 jobs among them since the end of 2016, for a combined growth rate of just three-tenths of one percent a year. Glens Falls metro has lost jobs since the end of 2016 and Watertown-Fort Drum has only gained 100 jobs in the past two-and-a-half years. The combined employment base of these five metropolitan areas is about 368,000, making them combined just barely larger than the Syracuse metro area and smaller than each of the four larger Upstate metro areas.

|

OTHER UPSTATE METRO AREAS(000) |

|||||

|

Dec.2010 |

Dec.2016 |

June.2019 |

|||

|

Dutchess-Putnam |

141.4 |

146.6 |

149.9 |

||

|

Utica-Rome |

129 |

127.6 |

128.6 |

||

|

Binghamton |

107.8 |

103.2 |

104.2 |

||

|

Ithaca |

59.1 |

63.9 |

66.5 |

||

|

Kingston |

59.8 |

61.9 |

64.4 |

||

|

Glens Falls |

54.5 |

56.2 |

55.5 |

||

|

Watertown-Ft.Drum |

42.9 |

42 |

42.1 |

||

|

Elmira |

39.5 |

36.8 |

37.2 |

||

The Labor Department's estimates for the 12 Upstate metropolitan areas show job gains of 45,000 since the end of 2016 to June 2019, with employment rising from 2.512 million to 2.557 million, or a growth rate of seven-tenths of one percent a year. The metropolitan areas of Upstate New York include about five-sixths of total employment in Upstate New York.

State Labor Department estimates for the non-metro areas of Upstate New York from 2016-2018 show job gains of a little over 4,000, for a growth rate of about four-tenths of one percent per year. The non-metro areas of Upstate New York have a little more than 500,000 jobs. They are one-sixth of Upstate New York employment and about 5% of total New York State employment.

The loss of population continues to be a challenge for sustaining economic growth in Upstate New York.

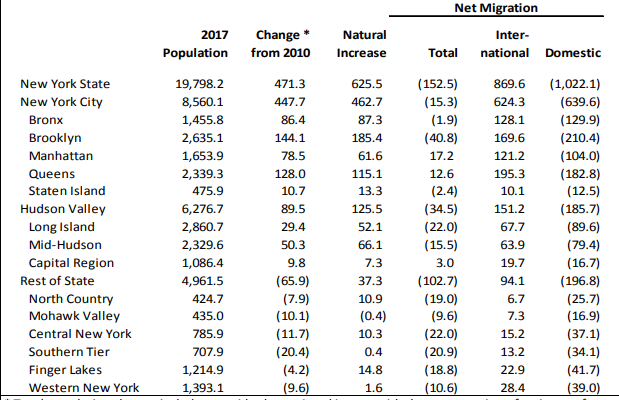

Below is a population growth table taken from the New York State Assembly's annual Economic and Revenue report from early 2019. It shows that New York City was 95% of the state's population growth between 2010 and 2017. The Hudson Valley, the Capital Region, and Long Island had small but positive population growth, but the rest of the Upstate New York regions lost population. Clearly these regions would benefit from new immigrants and increases in the allowable number of refugees into the United States.

And what of the Cuomo administration's efforts to help Upstate New York? The administration's main initiatives have included the Buffalo Billion, the $1.5 billion Upstate Revitalization Initiative, the Downtown Revitalization Initiative (some projects are in the Downstate area), the Albany Nanotechnology Initiative (begun during the Pataki administration), infrastructure spending in transportation and water and sewer upgrades, Tax-Free New York, cheap hydropower allocations from the State Power Authority, new investments in renewable technologies, especially windpower in the Lake Ontario area.

Surely these initiatives, and there are many, have had a positive impact, and are ongoing efforts that are budgeted for several years of future investment. But for them, the Upstate New York economy would likely be in even weaker condition.

Since the end of 2010, the aggregate numbers for Upstate show a net gain of 156,000 jobs. The state had a $10 billion deficit in 2011, the first year of the Cuomo administration, and there were spending cuts that affected state and local government employment, especially local schools.

Upstate New York lost 37,000 government jobs between 2010 and 2016, with those jobs stabilizing around 2013. Government jobs have remained relatively flat since that time in Upstate New York, so private sector employment is higher than the 156,000 net gain, probably about a 190,000 increase. It should also be noted that the State Labor Department's separate regional metro data show somewhat higher job growth numbers*.

The most recent year-over-year growth rates by state, from 2017 to 2018, showed 16 states had growth rates of seven-tenths of one percent per year, the Upstate New York growth rate, or less. Twenty-three states had growth rates of less than one percent. Upstate New York is not at the bottom of the nation in growth - it is slowly growing.

The state has also cut income, corporate, and property taxes, to the chagrin of progressives who would like to see stronger government spending. Governor Cuomo came into office in the aftermath of the Great Recession, and concern about whether New York taxes were undercutting business investment and encouraging out-migration affected early decision-making about how to grow the state's economy. More recently, recognition about the importance of infrastructure investment has replaced tax cuts as a priority, especially with the uncertain impact of federal tax reform on New York.

Since December 2010, the economy of the City of New York has essentially been carrying the state, with the city responsible for 863,000 of the 1.199 million jobs gained statewide.

(*The State Labor Department notes in its monthly employment press releases that the separate regional Metro area employment estimates do not match up (add up to the same numbers) as the aggregate employment numbers reported Statewide. The Statewide employment reports are estimated independently of the regional estimates. As a result there are discrepancies between subtracting New York City and its suburban areas from the statewide numbers to get the Upstate employment numbers, versus adding up each of the separate regional Upstate metro areas. Using aggregate numbers results in smaller employment growth totals for Upstate New York and the rest of the State outside New York City. The aggregate numbers show a growth rate of one-half of one percent a year; the regional numbers show .6-.7 tenths of one percent a year.)

***

Jim Brennan was a member of the New York State Assembly for 32 years, where he chaired four committees. On Twitter @JimBrennanNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.