Automatic Voter Registration is Good for Service Members, Veterans, and All New Yorkers

(photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

When I reported to my first duty as a Junior Officer of the United States Navy, my senior officer told me: “Your job is to take care of your people. Your people will take care of the ship.” This advice holds true outside the service: take care of your people, and they will take care of their family, their community, and their country.

It holds especially true when it comes to New York’s more than one million eligible voters who are not registered to vote. As a member of the armed services and as a veteran I’ve faced the burden of having to register to vote in multiple states, particularly here in New York, where the registration process is cumbersome, time-consuming, and inefficient. Now imagine if our state government systems actually worked together to reduce the bureaucracy for New Yorkers trying to navigate them. One significant way the U.S., and New York in particular, can make sure all can take part in the democratic process is by passing Automatic Voter Registration (AVR).

The idea is simple: instead of placing the onus of registration on individuals, eligible voters are automatically registered to vote by the state when they interact with a government agency.

Under New York’s current system, when someone moves within the state, they’re required to take the proactive step of updating their registration information. With AVR, the process would be made seamless. For example, if applying for a driver’s license or registering for classes, your info would be transmitted to the Board of Elections without any further action required on your part.

Critics argue that voters should take some responsibility for their registration but making it easier to register and preventing people from having to chase bureaucracy is a small price to pay, particularly for those who have borne the burden of war. The fact is, registration rates among active service members are consistently lower than among Americans generally. This is especially true in New York, which has the fifth largest veteran population of any state and is saddled with chronically low rates of registration.

For mobile or hard-to-reach populations like service members, as well as low income communities and communities of color, AVR would prove particularly effective, allowing your registration to follow you instead of vice versa. That also goes for military veterans suffering from physical or mental illness.

Beyond making the experience easier, AVR would also bring our agencies into the digital age. Imagine if our state government systems actually worked together to reduce bureaucratic wrangling that has come to define New York’s electoral process.

My career after the military has involved working with clients on digital transformations. I have observed organizations that I work with benefit from taking down the walls that separate their information systems. AVR is no different in the level of efficiency it would generate.

By now many of us are familiar with the 2016 incident in which the New York City Board of Elections erased 200,000 voters from the rolls. The reason for incidents like this is that our agencies tend to be siloed. New York requires residents to go online and fill out a separate form to register to vote, despite the fact that numerous agencies already collect the necessary information required to fill out voting forms.

AVR would break down these walls. A visit to the DMV or a Medicaid office would enable those agencies to electronically transmit your registration information to the BOE in a form that can be read by a computerized registrant list – saving time and money.

One study found that online and automated voter registrations saved Maricopa County, Arizona over $450,000 in 2008. It cost 33 cents to manually process an electronic application and an average of 3 cents to use a partially automated review process, compared with 83 cents for processing a paper registration form.

We have the opportunity to facilitate voter registration and make the process simpler while ridding our voter rolls of duplicates and eliminating incorrect and out-of-date addresses.

That’s why I went to Albany during a recent legislative hearing to share my experience.

Maintaining and protecting democracy requires more than service-men and -women going in harm’s way. It also requires providing citizens with not only the liberty, but the realistic ability, to exercise the right to vote and participate in the democratic dialogue.

We need to take care of our people by making it easier for all eligible voters so they can take care of our ship - this country. To ensure the full enjoyment of the rights for which my fellow veterans and I fought, and our current service-members continue to fight, the New York State Legislature should pass automatic voter registration this session.

***

Dolpha Freeman is a former U.S. Naval Officer and graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy. Dolpha currently works in a digital transformation consulting practice and resides in the Hudson Valley.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

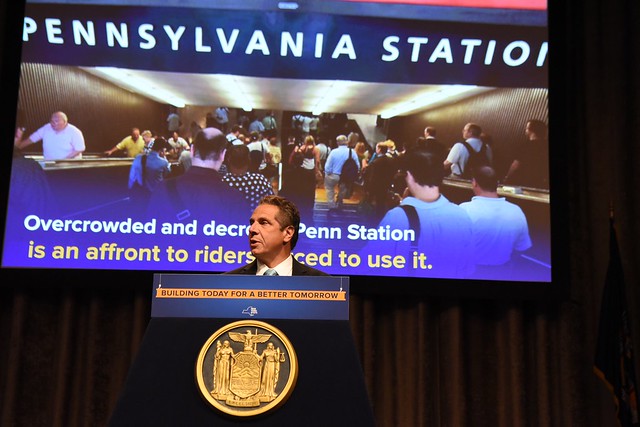

Penn Station Needs a Complete Overhaul. We Must Start Now.

(photo: Don Pollard/Governor's Office)

For decades, Penn Station has wreaked havoc on the lives of hardworking New Yorkers, and seriously stained our city’s reputation as a global cultural and economic hub. But all hope is not lost; the door is opening for significant improvements to finally be made.

We’re now just a few short years away from the opening of Moynihan Train Hall and East Side Access. These two important projects, which will temporarily reduce the number of passengers travelling through Penn, present a brief window for significant station improvements.

Transit experts have spoken extensively about the serious safety concerns within Penn Station—from overcrowded platforms, to a lack of accessible exits and signage on what to do in the event of an emergency. The recent announcement of an overhaul of the LIRR corridor and 7th Avenue entrance is a good first step, but there are a host of other improvements that should also be considered.

And beyond safety, it’s a matter of dignity, utility, and a vision for the future of the city we want to live in. Commuters shouldn’t have to settle with what we have.

They’ve seen a variety of great layouts and amenities – that work, by the way – at Washington D.C.’s Union Station, Boston’s South Station, and transit hubs overseas.

We need to look at Penn Station and the surrounding area in Midtown West comprehensively to solve this problem in a way that makes sense for commuters, residents, workers nearby, and New York as a whole.

Leading architects and designers have already created many informed and inspiring renderings and plans for what a new Penn Station could look like. While these designs are all different, they largely address the core issues of overcrowding, platform capacity, and accessibility.

Let’s be clear, Penn Station is not the way it is because of a lack of technical or planning knowhow.

It’s a political problem that can only be solved by bold, willing leadership that is committed to seeing this through from beginning to end.

It also means having a frank conversation about the future of Madison Square Garden, which sits atop the station—severely limiting natural light, air, and the ability to expand capacity.

For our leaders, fixing Penn Station must come down to our values as New Yorkers. We allowed our subways to enter a state of extreme disrepair that forces commuters onto already packed and delayed trains, or for some, abandoning the system all together. Deadlocked street traffic and slow bus speeds are the direct result of the failure to fix what’s going on underground. This is what happens when problems are left to fester.

If leaders don’t believe Penn Station is worth the investment of taxpayer dollars, they should be upfront about that and let voters know where they stand. If it’s a core issue they support, elected leaders should make it clear by calling for the creation of a Penn Station task force that would convene this year.

This task force should resemble the model used to evaluate congestion pricing and it should offer tangible next steps for a comprehensive fix—not a patchwork solution.

2019 has already been a unique year in Albany, with 39 new faces between the Assembly and Senate. Long Island was particularly active during the campaign season with several incumbents who were defeated—and is home to a major constituency that relies on Penn Station. As we rebuild our airports at JFK and LaGuardia and inaugurate new bridges like the Mario M. Cuomo Bridge spanning the Hudson, Penn Station must be our next big fix.

If we don’t get to work to fix Penn Station now, it won’t ever happen. It’s time to act.

***

State Senator Brad Hoylman represents parts of Manhattan, including Penn Station. On Twitter @BradHoylman.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Missing Pieces of the Criminal Justice Reform Conversation

(photo: Spencer T Tucker/City Council)

Many justice reformers welcome increased political support for constructive systemic changes. New York state government, for example, recently enacted reforms aimed at restricting the use of cash bail and reducing misdemeanor arrests. Many Democratic presidential candidates pointedly decry mass incarceration and our "broken" criminal justice system.

The most positive feature of this shifting landscape is the moral concern that it reflects, the relatively new recognition among pundits, politicians, and broader public that our criminal justice system is marked by a stark racial bias and that it undeniably violates our nation's core principle of, as Thomas Jefferson put it, providing "equal and exact justice" for all people.

What's missing, though, is certainty that all the attention will lead to meaningful changes in on-the-ground practices.

For instance, New York’s bail law includes significant exceptions regarding who can benefit from its provisions: judges can still set cash bail for New Yorkers with open warrants and with failures to appear in their histories. That’s many thousands of people.

Plus, and this point applies to all the reforms enacted, the agencies mainly responsible for the system’s current abuses, district attorneys and police, are still in power. They are in charge of implementing the changes and have ways at their disposal, overcharging being the most handy, to undermine them if they so choose.

Also, none of the Democratic presidential candidates who engage in indignant rhetoric on the issue have presented the kind of specific steps needed to reverse mass incarceration and to end systemic racism. We know from research and experience that the typical proposals that they and other mainstream politicians offer — body cameras, community policing, increased diversity, even marijuana legalization — will not make meaningful differences in current toxic practices. Jurisdictions that have enacted these changes still lock up far too many Americans, a disproportionate number of whom are Americans of color.

What's missing are policy reforms, proposed or enacted, that lead to institutional changes that are fundamental -- could say radical, in the sense that they address the "root" of the problem -- and significantly cut into the currently unchecked power of police and prosecutors.

One such step would involve repealing mandatory sentencing laws. It was the notorious Rockefeller Drug Laws -- enacted in New York in 1973, requiring a minimum prison term of 15 years (up to life) for the sale of 1 ounce or possession of 2 ounces of a hard drug -- that jump started the extraordinary expansion in imprisonment in the United States that we dub the "mass incarceration" movement. Eventually every state in the country and the federal government passed mandatory sentencing statutes, and the number of incarcerated Americans went from about 300,000 in the early 1970s to about 2.4 million today.

Abolishing these laws and restoring judicial discretion would substantially reduce the power of district attorneys to control case outcomes. Inevitably, courts would imprison a much smaller proportion of the people who the police funnel into the system.

Police practices are the most compelling factor driving the system's stark racial bias, especially in our nation's large cities. Jails hold mainly black and brown people because police arrest mainly black and brown people. Visit our city's arraignment courts where arrests are processed and a white defendant is a rare sight. On Rikers Island over 90% of the people locked up are non-white, there for two main reasons: they are too poor to afford bail and a NYPD officer has arrested them. Simply put, we cannot uproot the racism plaguing our justice system without drastically changing deeply discriminatory police practices.

Abusive police practices are firmly entrenched and long-standing -- New York City’s early civic leaders, for example, established the NYPD in 1845, expecting it to control and contain two unruly groups new to the city: recent Irish immigrants and free black people ("free" because the state abolished slavery in 1827). Modest modifications, like issuing criminal summonses instead of arresting people and implicit bias training, won't do. The changes must cut into the police's absolute power, which, after all, corrupts absolutely, to end persistent ways officers violate certain Americans' rights and well-being.

Specific examples include: ending quotas that pressure officers to make unnecessary arrests and stopping "broken windows" tactics targeting poor people of color for infractions virtually ignored in white communities; eliminating arenas of responsibility police now have that are better addressed by social services like school safety, sex work, homelessness, and mental health; and substantially cutting police budgets and personnel.

In September 1955, after learning that an all-white Mississippi jury acquitted the men who tortured and killed Emmett Till, Chester Himes, a novelist based in Harlem, commented: "The real horror comes when your dead brain must face the fact that we as a nation don't want it to stop. If we wanted to, we would." Now, as was true 64 years ago when Till's murderers went free, no mainstream politician will back the "radical" measures needed to end biased and abusive policing. Few, if any, will call for repealing mandatory sentencing laws -- all too electorally risky.

But if our leaders want to move beyond hand-ringing expressions of moral concern about our justice system's inhumane practices, if they want to fulfill our nation's founding "justice for all" promise, they, or, perhaps, even just one of them, will come forward and, in response to Mr. Himes' plaint, state: "Now we will."

***

Bob Gangi is the director of the Police Reform Organizing Project (PROP). On Twitter @GangiFromPROP.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.