How to Address Anti-Semitism in New York City, and Beyond

(photo: Ed Reed and Paige Polk/Mayoral Photography Office)

Like so many Jews, we are horrified and dismayed at the recent attacks on visibly Jewish people in New York City, in particular Hasidic and Haredi men. Anti-Semitic violence is on the upswing in the U.S. and in our city.

The NYPD reported 145 hate crimes between January and April; 82 of those incidents, 57%, were anti-Jewish. Hate crimes in general rose 67% in the first quarter of this year, and anti-Semitic hate crimes in particular increased by 82% over a similar period last year. White Christian nationalist violence, stoked by the election of Donald Trump, is on the rise — from New Zealand to New York.

This trend is unacceptable, but we can’t arrest or guard our way to real safety — the solution lies with communities.

Between attacks on Jewish people on the streets of New York, and the murders of Jews in our synagogues in Pittsburgh and Poway, we know that we need to address security concerns in a new way. So we understand why 39 members of the New York City Council, led by members of the Council’s Jewish Caucus, recently signed a letter urging Mayor de Blasio to use city funds to pay for armed, off-duty NYPD officers to guard houses of worship.

We all want to feel safe, especially in our churches, synagogues, and mosques, but city-funded armed police guards actually make some of us less safe, and cause many Jewish people of color, especially black Jews, to feel unwelcome in Jewish institutions. The truth is, policing cannot solve our problems — we will never arrest our way out of anti-Semitism.

As the city struggles to find money to deal with crises in homelessness, public housing, education, and more, paying cops to be security guards represents a back-door source of additional funding for the NYPD. This only escalates New York’s dramatic over-investment in the security state, instead of investing in our future.

We refuse to downplay the profound threat of anti-Semitic violence, or to dismiss the real fear and pain our community feels in this moment; yet we believe that there is a better way for the Jewish community to protect itself: by preventing hate violence in the first place. Armed guards are not a panacea — data show that the presence of police can actually attract shooters, and that, too often, police officers shoot bystanders in response to an attack, increasing the bloodshed rather than preventing it. In addition, arresting a suspect after an incident does not address the underlying tensions and ideologies that lead to hate violence; and increased penalties for hate crimes are unlikely to deter assailants from committing acts of violence.

Further, because communities of color are systematically overpoliced, a response to hate violence that emphasizes policing will inevitably have a negative impact on those communities, and reinforce the racist narrative that black people are more responsible for anti-Semitism than white Christians and other groups. (According to the NYPD’s own statistics, of the 69 anti-Jewish hate crimes in 2018 that resulted in an arrest, 40 of the alleged perpetrators were white, while 25 were black; nationally, from 2009–2018, 73% of all fatalities by violent extremists were caused by right wing actors.)

If we want to focus on prevention in New York City, the best approach is the Hate Violence Prevention Initiative that a coalition of Jewish, Arab, LGBTQ, and immigrant community organizations have presented to the New York City Council. The communities that these groups represent share a mutual interest in standing up to hate-motivated violence and white nationalism. All of us understand that hate violence and bias incidents can only be prevented in local communities, by local communities — not by police or prosecutors.

We need approaches that prevent violence through education and community-building, interrupt violence through community-based upstander/bystander trainings and rapid response at the local level, and repair damage through restorative justice, counseling, and peer-support. We oppose “zero tolerance” policies — an approach that is geared toward impressive sound bites, not effective hate violence reduction.

The Hate Violence Prevention Initiative will fund preventative education, restorative justice, upstander/bystander intervention trainings, and rapid response within communities when an incident has occurred.

"As a Jew of color, the initiative's focus on restorative justice also works better to provide safety for my community and all Jews, not only white Jews. A police presence outside a house of worship puts black Jews in danger." —co-author Arielle Korman

If we are serious about confronting the rise in hate crimes, we need an approach led by organizations in affected communities that is designed to confront the white supremacist ideology and anti-Semitic ideas fueling those crimes, and to ease the intra-communal tensions that surface them.

Up until now, the city has profoundly under-funded this type of approach. The dominant response to all hate violence incidents has been to call for increased policing and the filing of hate-crimes charges. We can do better. The recent arrest of a 12-year-old for chalking swastikas on a school playground demonstrates just how far we are from a targeted and proportional response that is likely to reduce hate violence in the future.

We find the rise in attacks on Jews terrifying but we know we’re not alone. We are inspired by the outpouring of care and solidarity from our neighbors when incidents of hate violence occur, and we are proud of the ways that many Jews have shown up for others in these difficult times.

For better or for worse, many of New York’s communities have a stake in standing up to right-wing, white nationalist ideology and the violence that it inspires. We believe that the only effective response to hate violence is one that cuts these ideas off at the root, and that binds together all of the communities impacted by bigotry — not one that pits us against each other.

***

Martha A. Ackelsberg is the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor Emerita of Government and Professor Emerita of the Study of Women & Gender, an author, and a member leader at Jews For Racial & Economic Justice (JFREJ). Arielle Korman is a graduate student at Columbia University, a cultural organizer, a member leader at JFREJ, and a co-founder of JFREJ’s Jews of Color Torah Academy.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

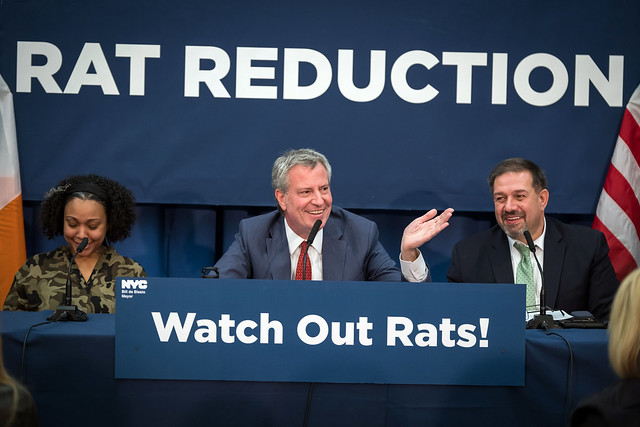

Stop the Rat Takeover with the Humble Brown Bin

(photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

When the New York Times announced that Rats Are Taking Over New York City, the widely-shared article and subsequent discussion overlooked one obvious remedy: reboot New York City’s stalled, neglected Organics Collection Program, and use it to take away a primary food source for rats near residential buildings.

Organics collection was introduced in New York City in 2013 and later incorporated into Mayor de Blasio’s OneNYC plan, which includes an ambitious “zero waste” goal: that the city will send nothing to landfills by 2030.

For residents in all of Manhattan and many neighborhoods in other boroughs, the city provides free plastic bins for curbside collection of organics: food and yard waste that make up 34% of all residential waste according to a 2017 New York City Department of Sanitation (DSNY) study cited at a 2018 City Council hearing. However, the program has stalled -– the city missed its planned deadline of having organics collection in every neighborhood by the end of 2018.

In the areas where the program currently operates, less than 11% of organic waste makes it into the brown bins. So most of New York City’s food waste winds up mixed in with other trash left in plastic bags on sidewalks overnight, and provides a ready food source for rats right next to residential buildings.

Rats can tote a slice of pizza down stairs or climb a subway pole, but they’ll never open the latch on top of a brown organics bin set out for curbside pickup. If New Yorkers could be persuaded (or mandated) to put all their household food waste into these city-provided bins, rats would be locked out of their current all-night buffet on our sidewalks.

In May 2018 after the DSNY froze the expansion of the organics collection program, Commissioner Kathryn Garcia promised “intensive outreach” to “grow participation” in areas where the program exists, but it is hard to find evidence of any such outreach.

The building where I live has been using a city organics bin for our food waste since the program began, but I’ve watched every other building on our block stop participating in the program. Here in Park Slope, Brooklyn, I’ve never seen any sort of outreach from the city to encourage participation, and in the last two years it has become more difficult to participate. DSNY used to drop off replacements for lost bins, but now it requires residents to drive to its office to pick up a new one. DSNY has also reduced the organics pickup schedule to one day per week instead of two.

The building where I live has been using a city organics bin for our food waste since the program began, but I’ve watched every other building on our block stop participating in the program. Here in Park Slope, Brooklyn, I’ve never seen any sort of outreach from the city to encourage participation, and in the last two years it has become more difficult to participate. DSNY used to drop off replacements for lost bins, but now it requires residents to drive to its office to pick up a new one. DSNY has also reduced the organics pickup schedule to one day per week instead of two.

The city missed an opportunity in not connecting organics collection to the rat problem. “Zero Waste” by 2030 has the same flaw as “Vision Zero” for traffic deaths -– it’s hard to see it as achievable, or as anything more than a pie-in-the-sky promise. “Separate all your garbage now and we’ll fix climate change in some future mayor’s term” is not nearly as compelling as “Put your food waste in this bin now so you don’t have to dodge rats when you walk out your front door.”

When the city gets complaints about rats in an area, in addition to putting out poison and adding a $7,000 solar-powered trash can to a local park, city workers also should help every residence and business in the area start using organics bins. Some advertising and hands-on assistance would make a huge difference, and make long-term environmental goals possible by focusing on New Yorkers’ quality of life in the short term.

Elected officials are often eager to declare an emergency and announce a quick, expensive response when a long-standing problem pops up in the news. Mayor de Blasio did this in 2017 when he proposed a $32 million “Rat Reduction Plan,” which included a bill to require some buildings to put out their trash at 4 a.m. (that bill never passed). Statistics cited in the Times story show the plan didn’t lead to long-term reductions. Persistent problems demand persistent effort and consistent messaging, especially when the solution requires millions of people to change their daily habits.

When every building in New York City has an organics bin, and every New Yorker has heard how this program can improve their quality of life, then we’ll be a step closer to a sustainable future, and also less likely to step on a rat when we walk down the sidewalk.

***

Tony Melone is a freelance musician and volunteer activist in Brooklyn. On Twitter @tonymelone.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Ending Health Disparities That Disproportionately Impact New Yorkers of Color

Council Member Carlina Rivera, left, one of the co-authors (photo: John McCarten/City Council)

New York City is one of the largest, most diverse, and advanced cities in the country – in fact, New Yorkers are living one-and-a-half years longer than a decade ago and nearly nine years longer than 25 years ago. Yet behind that positive sheen lies a shameful truth – our city persistently falls short in health outcomes for people of color.

As a New York City lawmaker chairing the committee that oversees our city’s largest public health system and as the founder and leader of the city’s largest physician-led nonprofit health care network, we are troubled that despite economic and technological leadership, our city continues to fall short on health basics.

Persistent health disparities are spread across all five of New York City’s boroughs, most noticeably in communities of color. So, with another Minority Health Month in the rear-view mirror, we are hoping to spur solutions and bring much needed attention to these crises beyond just one month. Whether it is tackling the epidemic of diabetes, maternal mortality rates, or depression and suicides, we can no longer take on these issues without highlighting the disparate rates at which these medical issues affect New Yorkers of color.

And the solutions to these challenges can’t just come from one sector. We need policymakers, community doctors on the front lines, and healthcare experts to all fight together for essential access to preventive care, increasing basic health education and literacy, and addressing the social determinants of health.

Our urban reality is stark: compared to their white neighbors, Latinx women are 60% more likely to be diagnosed with cervical cancer and are 70% more likely to receive late or no prenatal care; Asian-Americans are 30% more likely to be diagnosed with tuberculosis and 10% more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes; and African-Americans are 60% more likely to experience a stroke that could end in them becoming permanently disabled.

In addition, key survey findings in SOMOS’s State of Latino Health report highlighted a series of health disparities Latino New Yorkers struggle with every day. For example, 33 percent of Latinos don’t think people in their community get the health care they need, and 61 percent of providers think that Latinos face unique barriers that keep them from accessing health services.

Many of these conditions are exacerbated by what are known as social determinants of health, or more simply, the conditions in which New Yorkers live. These social determinants are attached to economic stability, education level, social and community context, health and health care; and neighborhood and built environment. And, every single one of these factors can determine a wide range of health risk outcomes.

Overall, New Yorkers who live in poverty and cultural isolation, including immigrant and first-generation New Yorkers, live underserved and in a political climate hostile to the historically disenfranchised. Put simply, this crisis is decades in the making, which is why the City Council Committee on Hospitals has been dedicated to examining these issues at our hearings and advocating for solutions from our city’s biggest medical providers.

We must improve health literacy through building awareness – and use cutting edge technology to meet diverse New Yorkers where they live and how they receive information. New York City has more languages and dialects than the United Nations, and we are stronger and more unique for it – yet in many communities our access to internet services is far too low. We need to translate simple, effective health literacy messages from nutrition and exercise to smoking cessation in order to better reach more families and employ digital and handheld technology to carry the message.

We must make sure nutrition and healthy eating are no longer the purview of elites. It’s worth repeating that farmers markets and supermarkets that specialize in natural, low-calorie, low-sugar, low-fat foods are economically far out of reach for far too many neighborhoods. Lowering food costs and making healthy food far more accessible and culturally relatable can make a huge difference in basic health for hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers who want to eat healthily but simply can’t afford it or aren’t exposed to it. And we know that local vendors who partake in farmers’ markets and sell to health food markets would like to reach more consumers.

Together, we are pursuing a collaborative agenda defined by our partnership, expertise and unique lived realities.

***

City Council Member Carlina Rivera represents the 2nd district, which includes portions of the Lower East Side in Manhattan, is Chair of the Council’s Committee on Hospitals and Co-Chair of the Council's Women’s Caucus. Dr. Ramon Tallaj is Chairman of SOMOS, a non-profit, physician-led network of more than 2,000 health care providers serving over 700,000 Medicaid beneficiaries in New York City, with providers delivering culturally competent care to patients in some of New York City’s most vulnerable populations.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.