Higher Marks for Scandal-ridden Legislature Decoded

The New York State Senate (photo via nysenate.gov)

Here's a fact for Ripley's Believe It Or Not: we New Yorkers seem to be feeling a lot better about our state legislature lately. Responding to a Mid-march Sienna survey, 41% of those polled expressed a "favorable opinion" of the Assembly, while 46% were unfavorable. A slightly larger proportion, 44%, expressed a favorable view the Senate, with 46% unfavorable. The gap between those favorable and those not (with those undecided excluded) was within the +/- 3.5% range of error for the poll. Startlingly, this means that a plurality of the state's registered voters may actually hold a positive view of our legislature.

One comparison brings the point home. Public approval of the way the U.S. Congress is doing its job over the past five years as measured by the Gallup poll has ranged between a low of 9% (March, 2013) and a high of 24% (May, 2011). Though the recent trend has been generally upward from the 2013 low point, the March, 2015 level of public approval of Congress's performance was 18%, less than half that for either of New York's legislative houses in the same month.

The highest recent levels of public approval of Congress, which of course has had its own massive troubles with non-performance and corruption, are below the lowest for the New York State Assembly (25%, recorded in August of 2010). The lowest recent approval for the New York Senate (20%) was recorded in August of 2009. Remember 2009? It was the chaotic year in which the Democrats, newly elected to the Senate majority, failed miserably when offered an opportunity to govern. The party's organization of the Senate was blocked by the notorious "Gang of Four" dissident Democrat members, three of whom later went to jail.

It is a massive understatement to note that corruption and ethical lapses in the legislature have not ceased being problems in New York over the past half-decade, the time during which approval of the state legislature has increased. According to Citizens Union's "Corruption Tracker," four legislators left office for criminal or ethical reasons in the 2009-2010 legislative session, three during 2011–2012, and eight during 2013-2014. Currently, four more are facing criminal charges: Republican Senate Deputy Majority Leader Tom Libous, former Democratic Senate Leader John Sampson, Democratic Assemblymember William Scarborough and, most recently and dramatically, former Democratic Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver.

Increased approval for the legislature side-by-side with persistent corruption: What's going on here? One possible (sad) answer is that corruption is accepted by most New Yorkers as part of our state's political DNA. Preeminent federalism scholar Dan Elazar argued that the Empire State is among those with an "individualistic political culture." Like our neighbors in New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, he thought that we in New York routinely expect our elected officials and others with a foothold in the system to advance their own interests, not some broader public interest. With politics already seen to be about personal gain, it is only a short step to tolerating corruption as a routine part of the game.

New York's feared ungovernability was a framing theme of the 2010 race for governor. Years of failing to meet the April 1 adoption deadline made late budgets a metaphor for state government dysfunction. Governor Andrew Cuomo highlighted the passage of on-time budgets in every year of his first term as evidence of bi-partisan executive-legislative collaboration that had, he said, moved the state from "dysfunction and chaos" to "government that is working."

Because the Assembly missed the mark by about three hours, there has been some caviling about whether the state budget was passed timely again this year. The man in the street would certainly say 'yes, it was.' A second explanation of the legislature's recently healthier poll scores may therefore be that they reflect New Yorkers' reasonable view that the institution lately has actually been performing better. The governor takes the credit but, as John Kennedy once said, "A rising tide lifts all boats."

Earlier this year, stung by the Silver indictment just a day after he had barely mentioned political reform in his State of the State address, Governor Cuomo built an ethics package into his budget, and pledged to give its adoption priority even over achieving timely passage for a fifth year in a row. In reaction, when surveyed by Sienna in February of 2015, New Yorkers said that corruption remained a serious problem, but gave priority to passing an on-time budget over ethics reforms. This highlights a third point. Citizens are making a distinction between good institutional performance and bad individual behavior, and saying that, on balance, achieving the former trumps punishing the later.

Contrary to his initial hard line, in the final budget negotiations Governor Cuomo accepted compromises on his ethics package while again achieving budget timeliness. In reaction, some argued critically that substance was more important than process. They said that the governor traded away too much this year on ethics and a number of other issues to achieve a budget by the April beginning of the fiscal year. This undervalues the long-term importance of demonstrating that government can work, and especially that legislatures can work, in a time of increased skepticism about the viability of representative democracy in New York and across the country.

Albert Einstein once famously defined insanity as "doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results." New York has been incrementally tightening regulations and increasing sanctions to reduce corruption in government for generations, to little apparent effect. Perhaps we should shift our focus to the front end of the process, to altering the expectations of the voters and reforming our deeply flawed electoral process (read: more competition, public financing of elections), and consequently the values and behavior of those we elect.

In our book Tales From the Sausage Factory, my co-author former Brooklyn Assemblymember Dan Feldman reports remembering thinking, when he first entered the historic chamber, "I knew that no one could take my job away from me for the next two years unless I committed a felony, and I knew I was not going to commit one." Electing 213 legislators to the Assembly and Senate with this predisposition would likely solve our corruption problem once and for all, while also assuring an even better functioning legislature.

***

Gerald Benjamin is Director, Center for Research Regional Education and Outreach (CRREO) - SUNY New Paltz

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Property Tax Reform Now!

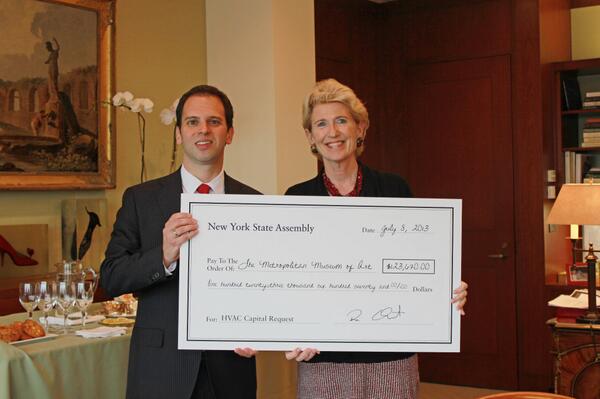

Assemblymember Quart (left), the author (photo: @DanQuartNY)

New York City's property tax system has been broken for years. It's byzantine at best, full of incomprehensible classifications and a mess of exemptions and abatements intended to correct earlier mistakes. The entire system is long overdue for reform.

The last major change to New York City's property tax system was the introduction of the Cooperative and Condominium Tax Abatement in 1996. Apartment buildings are assessed differently than single-family homes, subjecting homeowners in co-op and condo buildings to much higher tax burdens than those in single family homes. This tax break was designed to compensate for that inequity.

The abatement was intended to be a stopgap measure until the city created a comprehensive plan to solve inequities in the property tax system. In the intervening 18 years, the State Legislature has extended this abatement five times, each time tasking the Mayor's Office with devising a permanent solution to this problem. So far, no Mayor has done so.

This abatement is critical for many co-op and condo owners. Without it, their property taxes would increase substantially and immediately, leaving them suddenly unable to afford the apartments they have called home for many years.

What's more, this tax abatement preserves basic principles of fairness in our property tax system. There is simply no reason to tax homeowners who live in denser, more efficient, more environmentally sustainable apartment buildings at a higher rate than homeowners who live in detached houses.

While the entire property tax system still needs reform, it's time to stop pretending that this crucial tax abatement is a stopgap. After five renewals, it's clear that taxpayers and legislators alike believe in its importance. However, as long as the abatement remains temporary, it's a potential pawn in the inescapable political horsetrading in Albany. As long as it is temporary, co-op and condo owners are in peril.

It is time to permanently enshrine this abatement in our laws. Now that the budget is settled, I will be leading the charge to do just that, making this tax relief permanent and doing the right thing for co-op and condo owners across the city.

***

East Side Assemblymember Dan Quart is the author of a white paper detailing inequities in the NYC property tax system.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Sunset Park Redevelopment Proposal Misses the Mark

photo

On a recent Sunday afternoon, an impressive array of leaders from Sunset Park's tenant advocacy, environmental justice, small business, and community-based institutions, and their citywide allies gathered to announce their participation in a coalition to monitor and raise concerns about Jamestown Properties' $1 billion dollar redevelopment and rezoning proposal for Industry City.

Of key concern is the incongruity of the Industry City proposal for a hotel, university facility, and retail in one of the city's few remaining industrial, working waterfront neighborhoods. In addition to an extensive industrial building stock, Sunset Park has an inter-modal infrastructure and is anchored by two massive city-owned facilities - South Brooklyn Marine Terminal and Brooklyn Army Terminal. As one of the speakers noted, the last time a New York City waterfront neighborhood faced a similar scaled development proposal was in 2005, when Greenpoint-Williamsburg was rezoned with devastating consequences for the area's Latino community.

Sunset Park is a vibrant, working class, immigrant Latino-Asian neighborhood with a much-lauded walk to work population. Recent media accounts, however, describe a derelict, moribund, and gritty industrial waterfront. This skewed representation is similar to the New York Times coverage of Queens's pan-Latino, immigrant Roosevelt Avenue as a "corridor of vice" in order to rationalize a controversial proposal for an expanded Business Improvement District. These characterizations help prime a neighborhood for transformative private sector interventions such as that proposed by Jamestown Properties and their partners.

There is no question that deindustrialization and private and public disinvestment have taken a heavy toll on Sunset Park, but some businesses – not just storage and warehousing – have long co-existed in a manufacturing-maritime ecosystem. These include garment cutters, sewing subcontractors, furniture makers, auto repair shops, construction material suppliers, moving companies, and food manufacturers, wholesalers, and distributers. They may not be part of Jamestown Properties' vision of an artisanal and hip innovation-maker economy but these small businesses are an important part of Sunset Park's local economy and immigrant employment base.

In 2010, I met with two Chinese garment contractors who relocated their factories from Manhattan Chinatown to 39th Street in Sunset Park due to rising rents and real estate instability. One produced evening gowns for a Midtown Garment Center manufacturer and he was optimistic about the future since he had secured an affordable space for his business. A short three years later, the building 353 Fashion Inc. occupied was sold to a real estate investment company that has recently obtained a Department of Buildings permit to demolish the 7 story building. According to my review of the NYS Department of Labor Apparel Industry Taskforce data, the number of garment contractors at Industry City was halved from 39 to 20 in the year, following Jamestown Properties' acquisition of a 49.9% ownership share.

This past August, I met with a few Bush Terminal tenants including the owner of a furniture and cabinet manufacturer, Dean & Silva, who were concerned about their tenancy amid a growing buzz about transformative waterfront redevelopment. Given the spectacular views of the Upper New York Bay and the drumbeat that NYC's manufacturing future is premised on an innovation economy, these businesses may not be deemed the "highest and best" uses for Sunset Park's waterfront.

The Industry City proposal claims to generate 20,000 jobs but there is little detail to substantiate this projection. So far, the proposal and design renderings focus on the proposed hotel, retail streetscape, and bicycle path. What we do know about job creation in the innovation economy is based on a 2013 Pratt study of the Brooklyn Navy Yard which found that 60% of Navy Yard tenants employ fewer than five employees. Given the realities of modern manufacturing that innovators typically require small spaces and hire few employees, this leads one to wonder whether most of the projected jobs for Sunset Park residents will be generated by the planned hotel and expanded retail.

On a recent tour of the Brooklyn Army Terminal, the guide lamented the threat posed by "residential creep" in industrial districts but the immediate concern for Sunset Park's waterfront may be more appropriately described as "retail creep." Several years ago, then Federal Building #2 designated developer, Times Equities Inc., was unabashed in naming their proposed project: Sunset Marketplace. While the 2008 financial crisis doomed this project, the current owner of Federal Building #2 (renamed Liberty View Industrial Plaza) just announced that a Bed Bath and Beyond will lease more than 100,000 square feet for four of its retail outlets.

The threat of displacement due to rising property values is real not only for industrial businesses but also for the sizable residential population in Sunset Park's manufacturing zoned area. Grandfathered by the 1961 Zoning Resolution, Sunset Park's waterfront bounded by 65th and 15th Streets, 3rd Avenue, and the Upper New York Bay represents four census tracts which according to the most recent 2013 American Community Survey includes about 10,000 residents. Living adjacent to the Gowanus Expressway and the industrial waterfront, this population has been on the frontline of neighborhood environmental justice struggles. Now, they face another type of threat. Among this population, 66% are Latino and a third have incomes below the poverty line. The educational attainment level for an overwhelming majority (63%) of the adults is completion of high school at most. These are families at imminent risk of displacement.

Community stakeholders are right to raise concerns about Williamsburg in part because the city largely dismissed the Greenpoint-Williamsburg 197a plan in its 2005 rezoning of the industrial waterfront. After a 13-year planning process, Sunset Park's 197a, which focuses on protecting the manufacturing and maritime waterfront, was adopted by the New York City Council in 2009. That same year, NYC EDC designated Sunset Park a "sustainable urban industrial district" in its Sunset Park Waterfront Vision Plan.

UPROSE also recently completed a NYS Brownfield Opportunity Areas planning process which engaged community residents, small business owners, and local non-profit organizations in developing a plan for the remediation and redevelopment of waterfront sites. All three plans emphasize shared goals to protect and grow industrial employment, promote green manufacturing and climate resiliency, and increase the efficient movement of goods.

Along with UPROSE, organizations represented at the recent press event include Neighbors Helping Neighbors, Trinity Lutheran Church, So.Biz, Working Families, Association of Neighborhood and Housing Developers, New York City Environmental Justice Alliance, SEIU 32BJ, Teamsters Local 812, Pratt Center for Community Development, and ALIGN. It is a broad coalition with important demands.

Recent news that Mayor de Blasio is considering a ban on hotels as an "as of right" development in light manufacturing zones is a small but positive step towards protecting Sunset Park's industrial waterfront. We need all our elected officials to affirm Sunset Park as a working waterfront, to honor the years of hard work and good faith in community planning, and to advance developments that truly support a sustainable industrial district that is job intensive for local residents.

***

Tarry Hum is a professor at The City University of New York (CUNY) and author of Making a Global Immigrant Neighborhood. On Twitter @TarryHum.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.