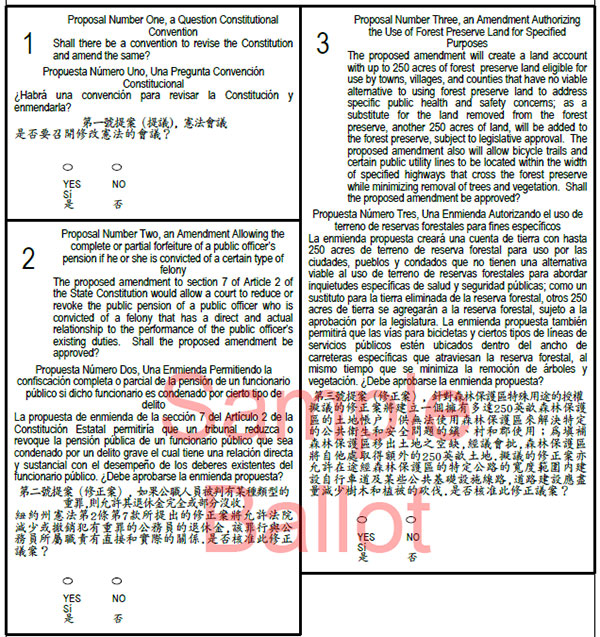

(sample ballot excerpt - image via NYC Board of Elections)

When New Yorkers vote on Nov. 7 on whether to call a state constitutional convention, the question they will see on the ballot is: “Shall there be a convention to revise the constitution and amend the same?” This ballot text is the only form of convention related media that every voter will see immediately before voting—and when many voters are most impressionable.

Unfortunately, this seemingly innocuous question is highly biased because it doesn’t specify whether it refers to the federal or New York state constitution. Close to 100% of New Yorkers know they have a national constitution, but less than half know they have a state constitution. Thus, millions of New Yorkers may go to the polls assuming that what is being referred to is the United States Constitution. And since Americans are taught to revere their federal constitution like the bible, the question could just as well have been worded: ‘Shall the Bible, written by god, be rewritten?”

In short, the ballot language is strongly biased against a “yes” vote.

In 1846, when this language was first inserted into New York’s Constitution, it wasn’t biased in the same sense that it wasn’t then biased to refer to voters as white males. Only since the Civil War, with the growing chasm between knowledge of the federal and New York state constitutions, did it become biased.

Prior to the Civil War and the passage of the 14th Amendment to the federal constitution (which extended federal rights protections to the states), states played a much greater role in American government. The pre-Civil War era was one of state rights, state power, and state glory. The federal government was often subservient to state government, provided far fewer services, and was even often viewed by some politicians as a stepping stone to serving in state government. Since the state and national constitutions were largely co-equal, students studied both. State constitutional reform was also often in the news, partly because New York’s constitution had been the subject of high-profile revision during every middle-aged adult’s lifetime (e.g., conventions in 1777, 1801, 1821, and 1846), something that wasn’t true of the federal constitution. Between 1803 and 1865 there were no federal constitutional amendments, let alone high profile conventions.

Today, in contrast, New York’s constitution is often treated as a ragamuffin. Those who attend New York’s K-12 schools, visit its leading museums, and watch its history on TV, will rarely if ever be told that New York even has a constitution, let alone what’s in it or how New York’s nine state constitutional conventions shaped it. In contrast, the federal constitution has retained and even raised its position atop its Bible-like pedestal.

To be fair, by the time most voters enter the voting booth on Nov. 7, they will know they have a state constitution. The ballot abstract provided by the New York State Board of Elections does explicitly refer to the constitution as a “State Constitution.” But the fraction of voters who read the abstract will be exposed to an arguably even worse type of bias. For the abstract describes only the cost of a convention; nowhere does it describe any benefits. Thus, a rational person who reads this description would infer that a convention only involves costs—which mimics the message being promoted by legislative leaders and others who are leading the campaign to oppose a “yes” vote.

Instead of focusing on a convention’s costs and other procedural details, the ballot abstract should explain the convention’s democratic purpose in the context of the constitution. This would include explaining why New York’s framers provided for two methods of constitutional amendment, why New York courts have ruled that calling a convention is an inalienable right of the people, and why New York’s constitution (Article XIX, §3) specifies that when there are two conflicting amendments ratified by the people, the convention-proposed one trumps the legislature-proposed one.

This year Evan Davis, a leading advocate for calling a convention and former Counsel to Governor Mario Cuomo, sued New York State’s Board of Elections regarding its placement of the convention referendum question on the ballot. The suit’s admirable goal was to have the question more prominently placed on the ballot. This would signal its importance to voters and thus encourage them to vote on it. The remedy sought, which the court denied, was to have the ballot question placed on the front side of the ballot, where voters choose candidates.

A better proposed remedy, which would have avoided forcing judges to decide on the relative importance of candidate versus referendum questions, would have been to place the two different categories of questions on different ballots. This remedy would have treated candidate and convention questions equally, and it is used by legislators in other states when they want to discourage voters from leaving a legislature-initiated constitutional amendment question blank.

On the other hand, since the convention question embodies New Yorkers’ most fundamental of all democratic rights—the people’s right to constitutional reform—it should arguably be given the most high-profile ballot position. Many states have granted it that position by calling a special election, but that remedy is both undesirable (e.g., it reduces turnout) and illegal (New York’s constitution specifies that the convention referendum be held at a general election).

My own preferred approach would be to eliminate government control over ballot media—a power that government officials routinely abuse despite claiming to practice objective ballot journalism. But as I argued in a prior column, New York currently lacks the election infrastructure to make this reform viable. Fixing that antediluvian infrastructure should be a priority for any convention the voters approve.

With only days to go before the election, the press should educate the public on the most basic constitutional and convention facts that New York’s public and non-profit educational institutions have shamefully failed to teach.

First, a New York state constitution exists, and the convention referendum refers to it.

Second, the New York constitution greatly differs from the federal constitution. It is about seven times as long (about 8,000 versus 55,000 words); full of provisions made obsolete by new federal laws; pockmarked with hundreds of legislatively-passed amendments that make the document incoherent and unreadable; and shunned by New York’s most prestigious educational institutions, including schools and museums, as unworthy of their educational efforts.

Third, the framers of New York’s convention process believed that it had not only costs but great benefits, as it is New York’s only available mechanism to bypass the Legislature’s gatekeeping power over constitutional amendment—an essential component of New Yorkers’ right of constitutional reform.

Fourth, the question’s obscure placement on the ballot should only signal incumbent state officials’ political self-interest, not the question’s importance as a safeguard of a vital democratic right--the people’s right to alter their constitution in the face of a legislature’s opposition. There is no more important question on the ballot, as signaled by the many millions of dollars New York’s most powerful legislative lobbying groups are spending to defeat it.

Addendum: Readers, including Karen Biesanz from the League of Women Voters, and Evan Davis from the Committee for a Constitutional Convention, have pointed out to me that the wording of the ballot question also misleadingly implies that a convention will not only propose but ratify amendments. In Ms. Biesanz’s words, it “implies that there WILL be revisions/amendments” despite a convention’s proposals not being “a done deal till the electorate votes to accept [them].” They have made an excellent point. The ballot’s wording bolsters the opposition’s strategy of implying that the people lack the power to vote a convention’s proposals up or down; it should have clarified that the people retain a veto power over any convention proposed constitutional reforms.

***

J.H. Snider is the author of "Does the World Really Belong to the Living? The Decline of the Constitutional Convention in New York and Other U.S. States 1776-2015" and editor of The New York State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.