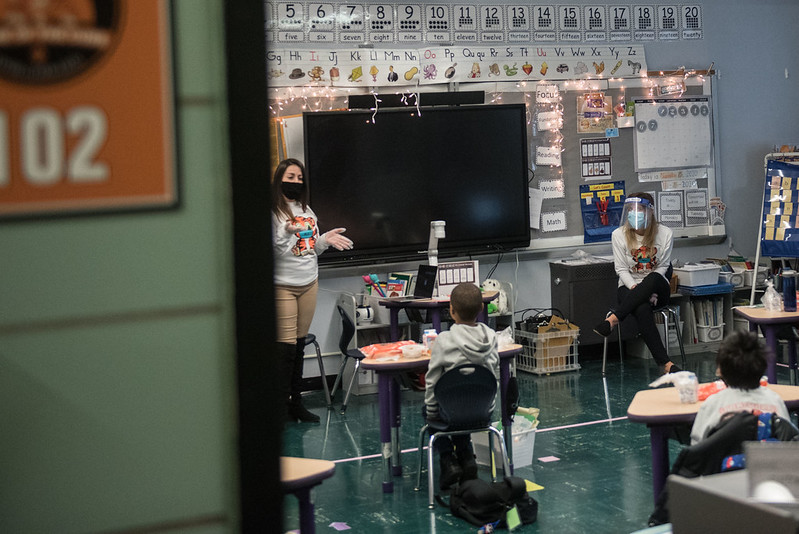

Pandemic education (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Leading Democratic candidates for mayor have appeared at several recent forums to outline their priorities on education and the possibility of running the country’s largest school system, as well as their strategies for achieving those aims. Discussion at the various forums, hosted by a number of diverse groups, was often focused on how the mayoral hopefuls would shape equitable and inclusive educational policy for New York City students, especially amid the fallout of the coronavirus crisis, which has exacerbated the city’s pre-existing racial and class disparities.

The pandemic has wreaked profound and continued havoc on education, with students and teachers approaching a full year of mostly online learning, and fits and starts of resumption of in-person instruction. The challenge of making up the loss of student learning is immense, and this comes on top of the several major crises facing the city’s school system and its 1 million students even before the pandemic struck.

Data show that the consequences of in-person school shutdowns will be extensive. One study found that students may lose on average five to nine months of learning by July 2021. Those findings are compounded for students of color, highlighting and compounding a starkly unequal education system. New York City has among the most segregated school systems in the country, and many tens of thousands of students are without stable housing or home internet access.

The mayoral race, which will be decided through the June party primaries and fall general election, includes well over 20 declared candidates, though only about 10 are considered in the ‘top tier’ of the crowded Democratic field and being invited to most of the forums hosted by advocacy groups and other organizations.

The recent education forums were hosted by Columbia Law and NYU’s Education Law and Policy Societies, the NYC Black Educators Coalition, the Council of School Supervisors and Administrators, PLACE NYC, Teens Take Charge, YA-YA Network, Teen Activist Project, and Urban Assembly. Candidates have also touched on education issues at a number of other forums, including those hosted by Empire State Indivisible, East Harlem Democratic Club, and more.

Participating candidates in one if not most of these forums where education-related stances have been offered and accumulated for this article include Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, former federal housing secretary Shaun Donovan, former city sanitation commissioner Kathryn Garcia, former top Wall Street executive Ray McGuire, City Council Member Carlos Menchaca, former nonprofit executive Dianne Morales, City Comptroller Scott Stringer, Maya Wiley, a civil rights attorney and former counsel to Mayor de Blasio, and former presidential candidate and entrepreneur Andrew Yang. (Former city veterans services commissioner Loree Sutton also participated in some of the forums, but on Wednesday, March 10 she dropped out of the race.)

Responses from mayoral hopefuls revealed significant differences in how they would shape and execute their education policy agendas, touching on a wide variety of broad and specific topics.

While candidates generally all said they want to integrate the city’s schools, they are divided on the desegregation policies they would implement as mayor. Some mayoral hopefuls agreed on overhauling admissions criteria and eliminating gifted and talented programs, for example, whereas others said they would keep the existing system with some more modest changes.

Candidates were also divided on policing in schools, with some in favor of defunding the NYPD and diverting funds to the Department of Education, including by removing both NYPD officers and school safety agents from schools, while others called for more minor changes to the current system, albeit all said they shared the goal of safe schools where students are treated fairly.

Eric Adams

“We have ignored Black and brown students in this city for far too long,” said Adams, who decried the “hidden racism in our Department of Education” as reflected in student achievement gaps, particularly those from historically marginalized backgrounds. “It is unimaginable that over 60% of Black and brown students do not meet proficiency every year,” he said.

Adams said the pandemic has resulted in a major drop in math skills among students, which he said was worrying given that “the jobs of the future” emphasize STEM education.

On getting students back on track after the loss of learning, Adams advocated for moving away from the agrarian calendar to include education in the summer months, extending hours in school throughout the week, and implementing schooling on weekends. “We must use remote learning in a real way to catch up,” he said, but did not explain how this would be accomplished given the shortfalls of remote learning during the pandemic, which Adams has regularly cited.

“80% of the child's brain develops within the first thousand days of life. No one is giving that real foundational instruction,” said Adams, who went on to say that he wants to provide all first-time mothers with a doula, including providing parents with education on nutrition, which he called a “cradle to career” plan. Adams has said his plan is for “pregnancy to profession” and that the “first classroom is in the mother’s womb.”

“If we don't educate, we will incarcerate,” he has said repeatedly on the campaign trail, emphasizing the important role education plays in ending the school-to-prison pipeline and noting that many people detained in city jails have learning disabilities like dyslexia that Adams says far too often go untreated, with severe negative consequences for individuals, families, and the city.

Adams wants to improve career and technical education programs and teaching real-world skills, such as financial literacy. On reading proficiency, Adams emphasized the importance of ensuring that children’s reading material is diverse, on top of ensuring teachers are properly trained.

Adams has called the city's deeply segregated schools "one of the most embarrassing things in our city," and said he would be "aggressive" as mayor in pursuing changes to the ways "we assign students to schools" and place students in classes within schools. The current system is hurting children of color, he said.

“Gifts are more than just exams,” Adams said. Although the borough president has previously decried the specialized high schools as “a Jim Crow school system,” Adams has since called for the creation of five more specialized high schools in the city, and emphasized creating gifted and talented programs in more low-income neighborhoods, providing paid-for test prep for students, diversifying the metrics used to evaluate students, and eliminating barriers to entry. Adams credited his decision change to community leaders who support the test. “I met with African American, Caribbean and Chinese leaders who are alumni of the specialized high schools,” said Adams.

“I believe the state should make that determination,” said Adams when asked whether he would support the repeal of the Hecht-Calandra Act, which created the SHSAT as the sole entrance criteria for the three largest specialized high schools in the city. “I'm not running for state office. I'm running for city office. They need to decide and debate that and give them the opportunity to come to a conclusion.” Asked if the mayor’s input in the matter is important, Adams said it is not.

Asked if the city not the state should have the authority to control the cap on charter schools in the five boroughs, Adams, a former state senator, similarly said, “I believe that should be a state decision.” Adams has indicated he is a supporter of charter schools on numerous occasions in the past, but has not made expanding the number of charter schools in the city a key campaign plank.

Asked whether law enforcement officers should be removed from schools, Adams said, “If we're talking about uniformed police officers, I say yes to that. If we're talking about removing from schools any level of public safety, I say no to that.” He went on to add that schools should “have properly trained individuals to deal with imminent danger,” like the current unarmed school safety agents, but he did not specify what sort of professionals with what credentials would fulfill those roles. Adams has also indicated he is against diverting funds from the NYPD into the Department of Education.

Asked how he would ensure equity for charter schools, Adams said, “I'm going to give you what you need based on your needs, not based on what everyone else has received.” He decried the “one-size-fits-all” approach regarding the distribution of funding and resources, saying he would allocate funding “to ensure [children] receive the resources they deserve.”

Adams noted the importance of engaging non-English speaking students, saying, “Teachers should reflect the diversity of our city.” He pointed out Brooklyn is home to many residents who speak a language other than English at home.

“When COVID hit our city, I didn’t go to the Hamptons. I went to public housing. I went to homeless shelters. I went to hospitals. I put a mattress on the floor at Brooklyn Borough Hall and spent five to six months there,” Adams said when asked about how he would support the educational needs of students who experienced homelessness during the pandemic, and making veiled references to competitors like McGuire and Yang. Adams committ ed to ensuring high-speed broadband access in every homeless shelter, as well as expediting housing rules to get unhoused students into permanent housing.

Adams criticized the current education system for “preparing our children to be factory employees and not owners of businesses.” He has repeatedly said that schooling needs to be reimagined toward critical thinking and practical skills. In addition to critical thinking, communication, and problem-solving skills, Adams emphasized the importance of teaching students tech skills. “Everyone may not go to college, but everyone should have the ability to be gainfully employed,” he argued. Adams explained that was why he allocated $5 million into the Brooklyn STEAM Center, to provide students with technical education programs and career pathways.

On mayoral control of the city’s public school system, Adams said he was supportive but would increase parent and principal involvement, and that he supports the mayor having to get reapproval from the state every couple of years.

Adams pointed out that tech industries regularly profit from New Yorkers’ personal data for advertising and marketing. To generate new revenue, Adams said he is supportive of legislation that would impose a data tax on tech companies, diverting funds “into our educational system” and ensuring technological and infrastructure improvements.

Shaun Donovan

Throughout the forums, Donovan is pitching himself as an experienced crisis manager qualified to lead the city’s recovery, including in education, spotlighting his educational policy plan, the most detailed so far of all the candidates. The plan would include a “cradle to career pipeline” of paid internships for every high school student, “deeper connections” into CUNY’s two-year and four-year colleges, ensuring that 60% of students achieve college credit while in high school, and commitments from leading chief executives within his first 100 days as mayor to hire Black and brown students. Donovan also plans to provide at least one paid job, apprenticeship, or internship to every high school student. His plan states that this goal will be accomplished by 2026. Meanwhile, Donovan pledged during the Teens Take Charge forum to implement a universal Summer Youth Employment Program in his first year as mayor.

Donovan acknowledged the current mayoral administration for its progress on reading proficiency and providing something of a roadmap for what needs to be accomplished in the post-pandemic era. “We need to double down on the universal literacy program,” which would be accomplished by increasing the number of early literacy coaches to support educators in classroom environments, he said.

In lieu of law enforcement presence in schools, Donovan said the city should add jobs for “coordinators” who would “focus on the social and emotional development of our kids to deal with the underlying challenges that often lead to violence.” He noted that he plans to add 150 social workers to schools as part of that effort, as well as opening a pathway into those coordinator roles, including de-escalation training, for those who currently serve schools in safety officer positions. This plan would reduce reliance on student suspensions and other disciplinary measures. Donovan pledged to remove metal detectors from schools, as well, citing his experience “[leading] the charge to stop giving military equipment to police forces across the country” when he served as the budget director during the Obama Administration.

He said he’d eliminate all admissions screens into middle schools and “some of the screens in high schools,” specifying time, attendance, and geographic screens in the latter case. He criticized special education screens for over identifying Black and Latino students; according to his policy proposal, he does not plan to eliminate special education screens, but will try to ensure that those screening tests are reviewed for any potential bias. He praised Brooklyn’s 15th school district for its affirmative policies that promote integration, saying those efforts should be replicated “much more broadly.”

Donovan said he would support the repeal of the Hecht-Calandra Act, which requires the Specialized High School Admissions Test (SHSAT) as the sole entrance criterion for the city's top specialized high schools. But he also stated that he would try to “modify the test, and if necessary, if we don't get results, get rid of it.” In addition to eliminating time, attendance, and geographic screens to high schools, Donovan said he would implement “weighted lotteries.”

On ensuring equal treatment for charter schools, Donovan avoided specifics but flexed his connections in Albany and Washington, saying, “I would go to the state. I would go to the federal government and work my deep relationships with President Biden, with all of the leadership in Congress and make sure that we got what New York City deserves to invest in every one of our schools.”

During the virtual forum outlining candidates’ state-level legislative and budget priorities, Donovan said the city should have the authority to control the cap on charter schools instead of the state.

And, Donovan also reiterated his 15-minute neighborhood plan when discussing having a good school for every student within walking distance.

Asked to suggest new ways to support students with disabilities through evidence-based programs, Donovan mentioned connections to former and current mayors nationwide, as well as former United States education secretaries, Arnie Duncan and John King, saying this enables him “to look at models that are working in other places.”

To address disparities among multi-language learners, Donovan said he would “open 450 new bilingual programs over four years in elementary, middle, and high schools” and create a pipeline for multilingual New Yorkers to become teachers, noting this would require partnership with CUNY.

Asked how he would address the achievement challenges disproportionately impacting Black students as a result of the pandemic, Donovan said, “The first thing I would do as mayor is bring my chancellor and engage in a listening tour around the city to make sure that I was hearing directly from Black and brown communities.” He pointed out that the first policy he proposed upon announcing his mayoral candidacy was to create a “chief equity officer” who would report directly to the mayor and “look at every issue across the city as an equity issue.” He also committed to improving educator diversity, saying, “I'm the only candidate that's made a specific commitment to getting to two-thirds of our teachers of color within the first term.”

On mayoral control of the city’s public school system, Donovan said he was supportive but would make some changes, including making it permanent: “get rid of this year-to-year uncertainty where our kids, principals, teachers, and parents are held hostage every year to the legislative process.” He also said he’d improve engagement among principals, Community Education Councils, and the Panel for Educational Policy, especially over budget decisions. He criticized the current administration’s failure to establish partnerships and coordination between the Department of Education and other city agencies, especially during the pandemic.

Kathryn Garcia

“We need to be prepared with rapid remediation” to address “the socio-emotional losses that have occurred” as a result of the pandemic, said Garcia, who has pitched herself as an experienced crisis manager, having filled several different key roles in the de Blasio administration, from overseeing the city’s sanitation department to distributing millions of meals to New Yorkers during covid and more. She said she would ensure that teachers “are trained in trauma.”

She pinpointed early childhood, ages zero to three, as a critical area for improvement in the city education system because learning during those years “sets you up for the rest of your school curriculum.” To this end, Garcia has proposed free childcare for families earning under $70,000 a year. She emphasized the importance of science-based literacy programs, highlighting the Wilson Reading System as a program the city should broadly implement. Garcia also noted that the city’s post-pandemic recovery should focus on “ensuring that we are educating our high school kids as well as our CUNY kids.” She cited graduates of Automotive High School, saying “they can’t get a job at the department of Sanitation.” Garcia added, “Those trucks have five computers in them. They need a whole different set of skills than the generation before.”

Asked if she would commit to removing law enforcement from schools and redirect NYPD funding to the Department of Education, Garcia said it would be on a school-by-school basis. “I would be guided by what principals have to say about the security at their buildings…but at the end of the day, kids need to feel safe to learn,” she said. Garcia has indicated she is not inclined to move significant funding away from the NYPD and said she would foster student safety through programs designed to reduce microaggressions and implicit bias.

Garcia criticized testing four-year-olds for gifted and talented programs, calling for the equal distribution of resources and enrichment programs, from music and art to additional math and coding, but has said she is not supportive of eliminating gifted and talented testing beyond the very earliest grade. Garcia also does not support removing high school admissions screens. She proposes opening new specialized high schools and guaranteeing admittance to students who graduate in the top 10% of their middle school class, citing the Texas higher education system as a successful example of this model.

Garcia also pledged to expand inclusive education for students with disabilities and bilingual education. She pointed out that some students do not have access to the services and providers they need in their neighborhoods, such as speech and physical therapists. “We need to make it in those areas that those [services] are available at the school building,” she said. Garcia went on to say that “early intervention” plays a critical role in “the trajectory for that kid’s entire educational life.”

On funding her education priorities, Garcia targeted “the black hole that is Tweed,” where the chancellor and their cabinet run the Department of Education, as a drain on resources. “There’s some offices, like on school culture — I don’t know what they do. There are several levels of superintendents and deputy superintendents and new vice chancellors that have all been created,” she said.

Garcia called for “a more direct relationship for the principals to the chancellor.” She also called the enrollment drop of 43,000 students from the public school system “incredibly concerning,” pointing out that school funding is generated in part from “all of those families that pay income and property taxes.” There is also per-pupil funding that comes in.

In addition to ensuring homeless students have a path to permanent housing, Garcia said the responsibility should fall on City Hall to “ensure there are no cracks between the agencies,” referring to the Department of Homeless Services and the Department of Education.

While most other candidates said they supported lowering the voting age to 16 in municipal elections, Garcia said she would keep the voting age at 18. She also differed from several other candidates in that she would not establish a paid Youth Advisory Council where youth would be included on decisions regarding educational policy that impact students, such as tuition hikes and budget cuts. She said she would support an unpaid version of this.

On mayoral control of schools, Garcia said she is supportive and would not make changes.

Ray McGuire

Running on a jobs-focused platform, McGuire’s approach to educational policy emphasizes education as a foundation for future professional success.

McGuire stressed the importance of his “cradle to career” strategy, which would target children’s education before pre-K by providing parents with childcare and services. As mayor, he said he would ensure that every child can read at grade level by the end of the third grade, which is also the current administration’s goal. To achieve this, McGuire said he would “create a New York City tutor corps during the course of the summer,” which he added later would be supplied by the private sector. McGuire also proposed “public-private partnerships” that aid students with professional development and finding employment, including summer jobs for all students who want one.

Asked how he would ensure equal treatment for charter schools, McGuire did not directly answer the question, but reiterated his “cradle to career” plan.

McGuire suggested a multi-pronged approach for addressing the academic development and socio-cultural needs of Black students, starting with “culturally responsive teaching” and “diverse leadership.” He also called for a clearer understanding of educational best practices among school leaders and teachers, but did not go into specifics about how this would be enacted on a policy level.

McGuire advocated for arts education “because we have not for a long time celebrated that [arts and culture], so I want to make certain that we invest that into the curriculum.” On real-world preparation, McGuire emphasized the importance of developing Black and brown students’ “financial literacy and digital competency,” so they can “compete the way I was able to,” referring to his education at Harvard and his career on Wall Street.

Although McGuire voted criticism for the increased emphasis on high-stakes testing, particularly for excluding Black and Hispanic students, he also said he would not eliminate traditional testing or other forms of standardized assessments from classrooms. “We need to have metrics, so that we can measure how well our children are progressing,” said McGuire.

On the SHSAT admissions exam into specialized high schools, McGuire said he would expand the criteria to include things like grades, recommendations, essays and extracurricular activities.” McGuire also argued that many students are not aware of the SHSAT admissions exam to begin with, saying he would “start much earlier to inform our students that the test is available” and “get them trained so that they can prepare for taking the test.”

Asked whether the NYPD should retain jurisdiction supervision of school safety agents, McGuire said such measures “need to be selective,” determined “by principal,” and “we should yield to their perspectives” on whether schools need to be policed or not. McGuire argued that “not all schools are in the same kind of crime-ridden areas,” adding that he “would prefer [school safety agents] to be civilian.” McGuire also cited his personal school experience as the ideal model, “where there was very little show of any kind of protective services, but you know you’re safe.

“Parental involvement is critical to [students’ academic success],” said McGuire when asked how he would address achievement challenges facing Black and brown students as a result of the pandemic. “We need to accommodate the parents, especially those who have different schedules,” he said, citing his personal experience of being raised by a single mother. Although he stressed the importance of the chancellor’s role in monitoring student success, McGuire said as mayor he would stay involved, as well. “We need to make sure that we hold the school officials accountable for making sure that the parents are involved,” including updating parents on students’ progress.

McGuire called mayoral control of the city’s public school system “essential,” saying he wants “to be held accountable.” Like the other candidates, McGuire said he would of course bring in his own schools chancellor, but he added that he has a shortlist already in mind.

Carlos Menchaca

Menchaca praised the “power of organizing,” citing the movement in School District 15, which partially overlaps with his Council district and where he was active in desegregation planning, to remove middle school screening and achieve more school diversity and equity. He emphasized a similar partnership among schools, educational leaders, parents, and students for his own larger approach to tackling the city’s educational recovery.

Menchaca noted that engaging non-English speakers would play a vital role in the city’s recovery, saying, “The first thing that we need to do is commit to a language access program to ensure that everyone gets quality information as we transition to a post-pandemic world.

On this, he promised to “fully fund translators and interpreters for every school.” He emphasized the need for new capital to fund schools before expressing his support for defunding the police and investing in “more socio-emotional support systems like social workers in our schools.” Menchaca noted that he voted “no” on the city’s budget last year because it did not remove law enforcement officers from schools nor truly defund the NYPD in a significant way. He also voiced support for capital investments that would introduce a municipal “Green New Deal.”

“Resources are concentrated in white neighborhoods, and that needs to change,” said Menchaca on desegregating schools. He recalled seeing iPads in the Department of Education that were not in homes during the pandemic, which he called “criminal.” He called for the removal of the Specialized High Schools Admissions Test (SHSAT) “to ensure that we give equal access,” adding that “every school should be funded like a specialized high school. Menchaca also said that internet access should be guaranteed not only in schools, but in students’ homes as well.

On addressing equity issues in charter schools, Menchaca cited his experience as a City Council member representing, among other areas, Sunset Park, where “we are now building seven new schools after years of the city not listening to our community,” explaining, “All we did was build a better relationship with the School Construction Authority” to hear students’ and parents’ concerns. As mayor, Menchaca said he would build upon this experience “to fund more schools,” adding that children “should not have to fight for space in any school.”

On students who experienced homelessness during the pandemic, Menchaca said, “Removing our dependence on shelters is key to my administration,” adding that he would create permanent, affordable housing.

He emphasized the importance of a Department of Education-led investigation into schools of District 75 “because that’s where some of the most vulnerable kids, our students with disabilities, are failing.

Dianne Morales

For Morales, a former educator herself, fostering students’ academic success after a year of unprecedented learning loss will hinge upon “addressing the mental health and the trauma that our children have experienced as a result of COVID-19.”

To do that, Morales has called to defund $3 billion from the police department’s roughly $6 billion budget and redirect some of those funds into the Department of Education, among other sectors and social services, though she has not yet detailed how this would be accomplished. Morales committed to “creating safe spaces” by “removing police from schools” and “ending police intervention in student emotional crises.” Instead, she wants to expand the number of social workers and counselors in schools, provide “culturally competent, healing-centered mental health staff,” and provide de-escalation training for Department of Education employees. Additionally, Morales called for reforming the discipline system overall, including abolishing suspensions, because it contributes to the school-to-prison pipeline, she said.

Morales proposed expanding the school day and school year to get students back on track academically. Additionally, she pledged to expand college prep programs, including counseling and information access, citing her experience in the nonprofit sectors, where she ran college prep programs. She added she would expand those programs to earlier grade levels, saying, “In kindergarten and first grade, middle-class families start talking to their children about the idea of college. We need to start engaging in those conversations with our children.”

On desegregating schools, Morales advocates for the removal of “all screenings and barriers to access,” including “redrawing district lines and boundaries,” and moving away from use of the Specialized High School Admissions Test (SHSAT). She said she would support the state repeal of the Hecht-Calandra Act, which mandates the SHSAT as the sole entrance criteria at the three most prestigious specialized high schools, adding that she would “organize to make it happen.”

Morales proposed expanding funding for translation and interpretation services for non-English speaking families, as well as recruiting an “increased pool of educators of color, including transgender and gender-nonconforming educators.”

Morales criticized gifted and talented programs as discriminatory, saying, “All of our children are gifted and talented. The New York City public schools should be the place where they discover their gifts and talents. Racist screens and testing do not support that process.”

On helping the charter school sector, Morales began by emphasizing historic inequities, saying, that the city “[has] taken away funding from our schools, from our housing, and from all of the things that we need people like us need in our communities to thrive.” She continued, “And that is one of the reasons why you have had to go to charter school, why your parents have had to find a better school for you than your neighborhood school, because your neighborhood school wasn't being funded and resourced the way it should be.”

As mayor, Morales pledged “to make sure that in public schools, Black and brown kids feel seen, they feel valued,” emphasizing safety, diverse teaching staff, and quality education. Morales said the city should have control of the charter school cap.

She pitched her experience as a nonprofit executive for an organization that operates shelters for families in playing a key role in supporting the 100,000 students who were homeless over the course of the last school year. She called for “a coordinated system,” pointing out how many students are forced to make long commutes after they’re placed in a shelter far from their school, resulting from a lack of communication between the Department of Homeless Services and the Department of Education. “There should be some specific sort of unit that is connected to the Department of Homeless Services that operates within the Department of Education.” She added, “We need to provide public broadband and access to everyone,” but did not detail how she would fund or implement this.

Morales emphasized the importance of science-aligned curricula in regards to student literacy, saying, “We need to make sure that all of our teachers are trained in those best practices and fully able to implement them in our classrooms.” But she cautioned against a one size fits all approach, citing her firsthand experience with her son, who wasn’t reading in the second grade as a result of “cookie-cutter reading instruction.” She said adapting teaching strategies to individual students’ needs is critical. Morales also advocated for “culturally responsive curriculum...that reflects the history and the experiences of all of our students.”

Scott Stringer

“The biggest challenge for the next mayor is to start to build a mental health initiative in the public schools,” began Stringer, referring to the trauma caused by the pandemic. He went on to say that he wants to expand de Blasio’s pre-kindergarten initiative, which he called “a tremendous success,” by increasing the number of childcare slots, especially for children coming from lower-income households. He cited collaboration with State Senator Jessica Ramos on state legislation that would help accomplish those goals (the two recently discussed their plan in an op-ed published by Gotham Gazette). He also called for a “teacher residency program,” citing the fact that 40% of teachers leave after five years, and hiring “1,000 teachers of all different backgrounds [per year].”

On policing in schools, Stringer said, “We’ve got to invest more in social workers and guidance counselors,” explaining his view that police intervention is unnecessary for disciplining students.

Further on mental health care, Stringer called for the removal of ThriveNYC, the city's sprawling $250 million per year mental health support effort at coordination and enhanced programming, in favor of “social justice infrastructure in our schools,” though he did not detail what this endeavor would look like if implemented. Relatedly, Stringer decried the criminalization of fare evasion “because people can’t afford the fares,” saying he would “not put more cops into the transit system.”

Citing the success of District 15 in Brooklyn on removing middle school screens, Stringer said he would drive racial integration by removing geographic screens at the middle school and high school levels, as well as support the repeal of the Hecht-Calandra Act and replace it with the seventh grade tests in math and English. Asked if he would remove other types of admissions screens more broadly, in addition to geographic screens, Stringer said he would “look at every bucket of exclusion,” but did not make any commitments. Although Stringer said his children were tested for the gifted and talented program so they could attend a school where chess was offered, Stringer decried the practice of testing four-year-olds for such programs overall.

Asked how he would support English language learners and students with disabilities, Stringer called New York “the global city,” and so instruction should be “culturally competent,” but did not give specific policy proposals.

“One of the things that I bring to the table is I've already done the audit,” said Stringer when asked how he would generate new funding for his educational policies. Stringer went on to say that the main source of wasted expenditures in the Department of Education spending was rooted in the cycle of chancellor appointments “and suddenly hundreds of millions of dollars in being spent on managing management…I know how to upend that bureaucracy.” He said also that as mayor he would “reset the relationship with Albany” to increase state and federal funding.

“We have to leverage CUNY to create a world-class workforce development program at a real scale and make community college free,” said Stringer of his plan to utilize CUNY as a hiring resource, which he says would cost $160 million a year. He emphasized jobs in telehealth and IT as part of this program, as well as expanding micro-credential opportunities beyond two- and four-year college programs.

“I do support mayoral control of the public school system, but I do not support a dictatorship,” said Stringer when asked how he would put control back in the hands of the community. He pointed to his experience as Manhattan Borough President during the Bloomberg administration when he appointed Patrick Sullivan to the city’s Panel for Educational Policy. According to Stringer, Sullivan organized with parents and helped bring them to the table on shaping the mayor’s education agenda. As mayor, Stringer said he would continue this legacy of leveraging bureaucratic power to advocate for parents.

Maya Wiley

According to Wiley, addressing the educational fallout as a result of the pandemic should involve a holistic transformation of the school system. “We have to look at the innovative programs we currently have in our system that have never been taken to scale,” said Wiley, citing Pathways In Technology Early College High School, or P-TECH, as an example.

Wiley said she has had firsthand experience with inequities in the educational system, recalling how her daughter’s anger and low self-esteem as a result of grappling with an undiagnosed learning difference. In addition to implementing evidence-based programs to address reading proficiency, Wiley emphasized “supporting Individualized Education Program teams” to ensure that students with learning differences are identified. She also called for the implementation of a “22nd century dual language learning system.”

Wiley stressed the importance of tackling the underlying emotional and psychological needs of students in the wake of the pandemic, especially for those who were housing insecure, experienced an increase in gun violence, or come from communities with high rates of covid deaths. “We can solve that [interrupted educational attainment] by investing and making sure we have social workers and school guidance counselors in every school.” On that note, Wiley committed to removing police from schools and diverting funding from the NYPD into the Department of Education for mental health services, although he did not specify how much she would disinvest from the NYPD. Her platform includes cognitive behavioral and dialectical behavioral therapy for students.

The issue of racial segregation in edcuation is personal for Wiley, she has said repeteadly, who referenced her experience attending the public school system. “I have been a Black child in a Black, segregated, overcrowded, and underfunded school,” she said. Wiley criticized admissions practices that target the income bracket of parents rather than the learning abilities of students. To develop effective policies and programs that drive integration, Wiley proposed “partnering with all the stakeholders: communities, parents, teachers, and principals.” She warned against a one-size-fits-all approach, saying that policies should vary across districts and boroughs.

Having chaired the School Diversity Advisory Group empaneled by Mayor de Blasio, Wiley has repeatedly said she stands by the panel’s sweeping recommendations to replace gifted and talented programs with broader enrichment models, redraw district lines, and move away from admissions screens in order to integrate the city’s schools. But, she has not made school integration, or education for that matter, a focus of her campaign thus far.

“You will get what you need,” Wiley said of students in the charter school system. Wiley was vague on details, but suggested “creating new and different kinds of classrooms, ones that are much more engaging for what you want to learn.”

Wiley pledged to expand extracurricular opportunities for Black, brown, and Asian students but did not provide much detail, although she did say she would partner with communities to decide what extracurriculars are most needed. She also pledged to ensure student journalists are given city press passes.

On addressing the needs of unhoused students, Wiley pitched her experience as counsel to Mayor de Blasio for more than two years, during which time she spearheaded the mayor’s broadband expansion strategy. She also spotlighted her “$10 billion capital construction plan that is going to include permanently affordable housing,” one of the key early pillars of her campaign platform.

Asked how she would reimagine the public education system so that it meets the academic development and socio-cultural needs of Black students, Wiley pointed to the Bronx Collaborative Schools Plan as a successful model of improving teacher retention rates, explaining that paying teachers higher salaries attracts highly qualified teachers. Wiley called for implicit bias training in schools.

On generating funding for educational policies, Wiley pushed for state funding saying, “We need to go and get the money Albany owes us,” referring to the Campaign for Fiscal Equity settlement, as well as federal funding, including Title I funds. Wiley also said he would pursue a wealth tax as mayor, and she has backed the full package of state-level tax increases on top earners, corporations, and Wall Street activity known as Invest In Our New York.

Wiley said she would focus on rebuilding the public’s trust in the Department of Education.

Andrew Yang

“The truth is that online school has been demonstrated to be only 30% to 70% as effective as in-person instruction,” Yang began, when asked how he would address achievement challenges facing Black and brown students as a result of the pandemic. “We should be fighting harder to reopen our schools right now, and that’s doubly true for communities who are in danger of falling further behind,” he said, and he has specifically referred to students with learning differences. He advocated for “a more adaptive response” overall, but didn’t specify what this would entail.

Yang pointed out that students’ academic achievement goes beyond the influence of individual teachers and is something that should be targeted at a systemic level. “Two-thirds of our kids’ educational outcomes are determined outside of school,” including time spent with parents, nutrition, and stress levels at home, he said, “but we hold you [teachers] a hundred percent responsible.” Yang added that “recruiting diverse teachers and educators that reflect the community” is a crucial component of improving the public educational system.

A former chief executive at a Manhattan-based test preparation company, Yang defended testing for gifted and talented programs, saying, “I’m not a get-rid-of-the-test guy. I’m someone who believes in teachers.” Eradicating gifted and talented programs without an alternative solution would be “a mistake,” Yang said. He also expressed support for academic screening more generally, saying, “If you get rid of the screenings, it doesn’t mean you stopped failing our kids.” But later in the same forum, when asked about the efficacy of the especially high-stakes, Specialized High Schools Admissions Test (SHSAT), Yang did say such methods cannot detect a child’s full range of skills and talents and other criteria should be taken into consideration for admissions, more along college lines. Yang argued that teachers should be trusted to identify students for gifted and talented programs instead of relying on testing as the sole determinant. He also called for creating two new specialized high schools in each borough.

Overall, Yang has not said very much about whether he would focus on trying to desegregate the city’s schools.

Asked about the pandemic-era drop in city school enrollment, Yang suggested that the recent suspension of gifted and talented testing could exacerbate the problem. “We should not have any illusions about the fact that these two numbers are directly related,” said Yang. He went on to add that parents are “voting with their feet,” citing friends of his who are leaving the city.

While Yang did not directly answer whether the NYPD should retain supervision of school safety agents, he argued that some safety measures in schools, such as active shooter drills, go too far, and undermine students’ sense of safety. “There's this I think political pressure to feel like you're doing all you can to quote-unquote, keep our children safe. But sometimes those measures may not be having their desired effect,” said Yang. He went on to suggest that the implementation and the severity of such measures should be determined by “the principal, the administrators, and the parents.”

On improving teacher retention rates, Yang said, “We need to have white educators not outsource responsibility for the Black students,” pointing out that this trend creates additional labor for teachers of color and adversely impacts retention. He advocated for stronger support of teachers, especially for those of color, and suggested augmenting the NYC Teaching Fellows program and further investing in professional development services for teachers.

Asked how he would support LGBTQIA+ students, Yang suggested providing students with “individual mentors and resources,” as well as implementing sexuality and gender diversity education from pre-K onward.

Yang argued that he’s particularly equipped to address the needs of students with disabilities because he’s the parent of a child with special needs. “When the city does not meet the needs of a special needs family, the city often ends up paying more, not less,” said Yang, who has one son who is autistic. He argued that systemic barriers play a role in preventing students with special needs from claiming vouchers for individualized education plans, saying “there was a lot of bureaucracy involved” when he secured one for his son.

Asked about providing students K through 12 with a curriculum that highlights contributions of Black and brown people, Yang said that education should reflect the diversity of the city. At a later forum, he said Black history should be integrated throughout the curriculum and not as an isolated unit, saying, “American history is Black history.”

He emphasized that investment in arts education is crucial “because the data shows that that actually results in better outcomes” for students even though arts are typically underfunded and the first to be cut from budgets. He also proposed improving financial literacy among students, providing them with “investment portfolios, either mock or preferably real,” arguing that handling real money would help them learn “much more actively.” He added, “We also need to educate or emphasize and invest in technical, vocational and apprenticeship programs and not pretend that all of our kids are going to be heading to a four-year college.”

On mayoral control of schools, Yang said “A mayoral candidate not wanting control of the schools would be like a principal not wanting control of something vital to your school’s success.”

***

by Allison Smith for Gotham Gazette

@allison_n_smith @GothamGazette