The Coronavirus Crisis Must Open Our Eyes to the Flaws of the New New York

Mayor de Blasio at a supportive housing site (photo: Demetrius Freeman/Mayor's Office)

As our great city faces its most challenging crisis in the past 100 years, it has revealed to all of us how the city has radically changed in the past few decades.

The virus has now put a spotlight on the critical shortage of hospital beds and medical equipment like ventilators. In fact New York City ICU bed capacity ranks in the bottom quarter nationally. If you have lived in the city for over 40 years, as I have, you likely recall how many hospitals have closed and not been replaced.

But the current crisis also shows other deficiencies of the new New York of the past decade or so, even with all its wealth and abundance. These limits to the social fabric must be addressed as we look toward a rejuvenated post-coronavirus New York City.

I vividly remember visiting my assistant’s son as he and many other young men were suffering from the scourge of AIDS at St. Vincent's Hospital in Greenwich Village. This once-great medical center is now home to luxury condominiums, a conversion emblematic of troubling trends we’ve seen in our city. I can’t help but think of St. Vincent’s today as our hospitals overflow with coronavirus patients and we build pop-up facilities in parks and convention centers, while welcoming a Navy hospital ship to the Hudson.

We must place a total moratorium on the closure of hospitals in New York City, even if it means massive government support for these institutions whose importance has become even more evident during this crisis.

As our city has seen its population surge to 8.5 million and the yearly total of tourists climb to over 60 million a year, we’ve seen a city more crowded than ever. The subways were moving 4 million people a day in overcrowded trains, which was probably a factor in the spread of this virus. Experts say keep six feet away from another person to ensure some degree of safety, but many times the person next to us on our train is just 6 inches away, if that!

The surge in population over the past two decades based on foreign and domestic migration to the city, following in the grand tradition of New York as a place of opportunity and refuge, has contributed to a severe shortage of housing and record homelessness. There are now 58,000 men, women, and children living in our main city shelter system at a cost of $2 billion a year, with thousands of others in various other shelter accommodations. There are also roughly 3,500 homeless people sleeping on our streets and subways. The city is reporting a growing number of positive COVID-19 diagnoses in the shelter system and on the street, and some homeless people have already died after contracting the virus.

This scourge should once again put the spotlight on the need for low-income housing and, more importantly, supportive housing for those that are deeply afflicted by mental illness and drug addiction. And it should lead to a massive effort toward bringing many thousands of both types of housing online as quickly as possible.

In addition, the city’s public housing system, home to more than 400,000 tenants, is on the verge of collapse, and is also being rattled by the toll of the coronavirus. The city must take measures to safeguard NYCHA tenants, and must not now allow this very valuable resource to disappear as it has the hospitals. A NYCHA rescue plan must move ahead at full speed.

We also have a severe shortage of psychiatric beds to serve the most seriously mentally ill, including some of those individuals residing in shelters and sleeping on the streets and subways. There’s been a 15% decline in these beds in the past few years, continuing a longer-term trend. We must declare an immediate freeze on the closure of such facilities. The noble experiment, started 40 years ago, to release mentally ill patients from institutions and into the community has not been a total success and we need to admit that and increase, not decrease, the number of inpatient beds and outpatient treatment centers.

Our city is not only the epicenter of the virus in this country it is also the epicenter of income inequality, with 40% of the population living at or near the poverty level. We cannot continue to allow the destruction of moderately-priced apartments, such as I often see on the Upper East Side, where several floors of modest apartments, existing above a retail store, are torn down to make way for luxury housing. The city must declare a moratorium on this type of development. In addition, taxes must be increased on luxury apartments and their residents so that the city can meet the needs of those in need.

I am a proud New Yorker who has lived here all my life, and I am not giving up on our city, and I am confident we will rebound, but this horrible virus should open our eyes to the need to make changes to ensure our city is a great one for all in the future. Next year we will be electing a new mayor, and we must insist on that person being a visionary with important new ideas and not a custodian of the status quo

***

Robert Mascali is a former Deputy Commissioner at the New York City Department of Homeless Services and a former Vice President for Supportive Housing at Women in Need.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Surveillance and The City: A New York Dictatorship?

Gov. Cuomo at one of his coronavirus briefings (photo: Mike Groll/Governor's Office)

The consequences of poor social distancing, inadequate supply chains, and nearly every other facet of our COVID-19 calamity are nothing short of life and death. But as New York endures a disaster unlike any in our lifetimes, as we see our morgues filled and our store shelves stripped bare, this teeming tidal wave of death might upend most fundamental assumptions about our way of life.

We are about to face a deeply dangerous moment, not just because of COVID-19, but because of the extreme measures we use to stop it. As the weight of a previously unimaginable magnitude of human suffering turns the bedrock of civil society to quicksand, we run the risk that our core institutions might buckle and that we will undermine the rule of law as we know it.

If one looks for an American precedent for the extraordinary powers granted Governor Andrew Cuomo in this crisis, one will come up short. Whether you look at past pandemics or times of war, never before has our state entrusted one man with so much control over so many, with so few safeguards. Our courts are shuttered, our legislators are struggling to meet, and more and more reliance is placed in the executive branch. Since March 7, more than a dozen executive orders have modified everything from licensure requirements for funeral directors, to medical malpractice liability, to environmental protection laws, and even our election timelines.

No, there is no precedent in American history for this type of emergency action, but there are ancient parallels to a society where, “in times of plague,” a leader would be given extraordinary powers: the Roman Republic.

Long before the virtues of the Republic’s rule gave way to the tyranny of imperial Caesars, the Roman Senate saw the appointment of temporary “dictatores” as an emergency measure to counter existential threats, or as we would call them today “dictators.” Many will recoil at the use of the term “dictator,” with its modern-day connotations. The word may be centuries old, but it’s typically associated with modern-day war criminals — men marked by their violence and human rights violations. The dictators of Rome were a different creature, a single official granted extraordinary powers, but subject to one overriding restriction: temporary rule.

Unlike the dictators of today, whose tenure is often marked by permanent power, the dictators of Rome were a short-lived ‘necessary evil,’ citizens of the republic granted singular control for six months and no more. They were a walking contradiction, men given unilateral control to safeguard a society whose overarching aim was to prevent the consolidation of power. Their role was to suspend republicanism for a short time to safeguard it for the longer-term.

A “Dictator’s authority was bounded only by the requirement that he fulfill his task or lay down his power within a set time, and the requirement that he not change the constitution,” wrote Nomi Claire Lazar in “States of Emergency in Liberal Democracies.” As I explained in last-month’s column, Governor Cuomo’s new emergency power has only two limits: he cannot change the Constitution, and his powers expire next year. Until that time, Cuomo can repeal or enact any law that he declares is needed to respond to COVID-19, any law, so long as he doesn’t violate the Constitution. And he hasn’t let that power go idle, introducing a new executive order (on average) every other day.

At a time when Cuomo has unprecedented popularity, when many of his emergency actions are saving lives, I know how few will care about “legal niceties” of checks and balances. But if we continue to rewrite the rules that have governed New York State since 1777, we have to be crystal clear about how we prevent these changes from undermining the values that are central to an open and democratic society.

It’s hard to imagine how New York’s founders, the men and women who wrote lengthy treatises on the need to “expel civil tyranny” might respond to a governor so empowered and emboldened as the one we have now. They too were students of history and knew well that those granted extraordinary powers to face extraordinary threats are rarely willing to part with them.

The sad truth is that there is no one right answer on what to do. If we blind ourselves to the crisis and fetishize the separation of powers, it will only slow our response and cost lives. But if we simply empower the executive and call for his actions, we create truly unprecedented dangers to democracy. A single man, free to act without approval or oversight, will make mistakes. Competing viewpoints are not merely a philosophical luxury, they are key to navigating complex decisions. This is why the legislature must keep a close eye on Cuomo’s actions, reasserting its authority and overriding his decrees when needed.

The reason New York kept checks on the powers of governors, even in times of crisis, for nearly 250 years is because we know that human beings are fallible. We know they will make mistakes. And we know that left to their own devices, they will wield power to their own ends. Let’s just hope that we follow the example of those earlier Romans and insist that no matter how grave this pandemic becomes, that we make sure the dictator yields his powers after a brief time, even if the threat remains.

***

Albert Fox Cahn is the founder and executive director of The Surveillance Technology Oversight Project (S.T.O.P.) at the Urban Justice Center, a New York-based civil rights and privacy group and a fellow at the Engelberg Center for Innovation Law & Policy at N.Y.U. School of Law. He writes the monthly Surveillance and the City column at Gotham Gazette. On Twitter @FoxCahn & @STOPSpyingNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Coronavirus Tests New York City Schools

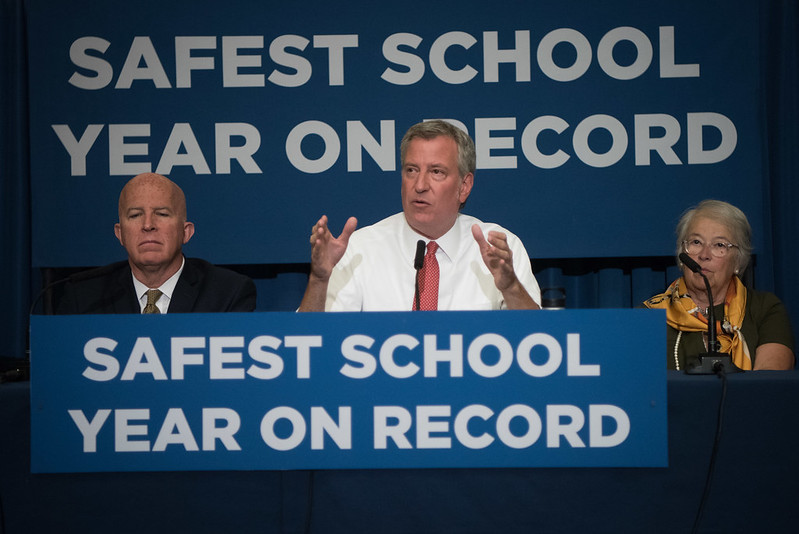

(photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Mayor de Blasio faced a short-answer, timed test: whether and when to close New York City's public schools. It was not an easy question. But his delay in answering and failure to adequately prepare has been costly in lives and learning. We continue to pay the price.

Even where the coronavirus outbreak was less severe and despite ambiguous advice from the CDC, district after district, state after state, had already decided to close their schools. But de Blasio hung on, ignoring dire warnings of community spread from his own Health Department.

At the city Department of Education, controlled by the Mayor and headed by Chancellor Richard Carranza, little preparation for the pandemic seems to have taken place, a fatal error debilitating operational effectiveness and public confidence.

When visiting schools in early March, I questioned principals on information coming from the central Department of Education. One said she had only been sent an extra bottle of Purell. Most were only aware of generic advice on personal hygiene and closure in case of student or staff illness due to COVID-19. But there was no well-known protocol for how families or personnel were to report this, especially in the absence of widespread testing, rapid confirmation, or detailed chains of contact. There was no special guidance on handling coronavirus-related student and faculty absenteeism and other looming administrative issues. Experienced principals with deep connection to their school communities and district liaisons felt ready to report exposures. Less adept leaders were in the dark.

There was no evidence that a distance learning order was just days away. Left unasked were critical questions of device availability for teachers and students, home bandwidth, and curriculum. Needs of home insecure, disabled, and English-as-a-new-language students and their families were ignored at the highest levels despite vigorous hand-waving by their advocates inside and outside the Department of Education.

Finally, after the Mayor precipitously announced on a Sunday night that schools would be closed the next day, he and the Chancellor endangered tens of thousands of teachers and administrators by ordering them into close contact the following week to revamp their classes for mass distance learning. Forgotten in the melee that followed were privacy concerns with the widely-adopted Zoom video platform that was easily hacked and shared student information with third party vendors in violation of the federal Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA).

Now we're in for the long-haul, if the Mayor and Governor can get their acts together to agree on closing schools through June and instituting distance learning opportunities at least through the summer.

The Chancellor is given to repeating that "We're building the plane while we fly it." Would that ever be the case, the plane would crash. So it is with a school system carrying over a million kids, attended to by more than that number of parents and other care-givers.

It's time to land that plane, give the administration, educators, students, and their adult protectors time to re-engineer jerry-rigged instructional and administrative policies that have left us -- let's face it -- without a functional public education system for over a month. We don't have attendance information. We’re just starting to learn how many teachers, principals, and other front-line school staff have taken sick or died. Promotion policies, tenure decisions, acceptable and accessible online platforms, and a thousand other critical decisions have yet to be made.

If we have gained any wisdom from this month of havoc, let's use a hiatus to make public education more equal and available as the current pandemic rages, with expected resurgence this fall and beyond. I propose two weeks: one for the DOE to re-engineer and a second for professional development (not in person, of course). Let's not let de Blasio's original sin of delayed preparation or Carranza's self-congratulatory stiff-upper-lip bromides keep us from addressing the long-term educational challenges ahead.

***

David C. Bloomfield is Professor of Education Leadership, Law and Policy at Brooklyn College and The CUNY Graduate Center. On Twitter @BloomfieldDavid.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.