Housing Squeeze Shows No Sign of Easing

To anyone look for an apartment in New York's City "free market," affordable housing can seem to be an oxymoron. While a well-known real-estate developer recently claimed that any housing rented or sold in New York City was affordable to the particular renter or purchaser, when the usual standards are applied many New Yorkers live in unaffordable conditions.

Generally, affordable means spending no more than 30 percent of household income on housing. For a household with an income of $100,000, affordable housing then would mean rent, utilities and other charges (but not phone and cable) or mortgage, maintenance and utilities would amount to no more than $2,775 per month. For New Yorkers at 80 percent of the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development median ($56,570), which the department considers the top of lower income, the figure would be about $1,575.

U.S. Rep. Anthony Weiner’s recent report that 28 percent of New York households who rent spend more than half their incomes on housing and his call for increased federal subsidies, public housing and other government measures served as yet another reminder of the severe problems of housing affordability in New York City and the lack of government action to remedy it.

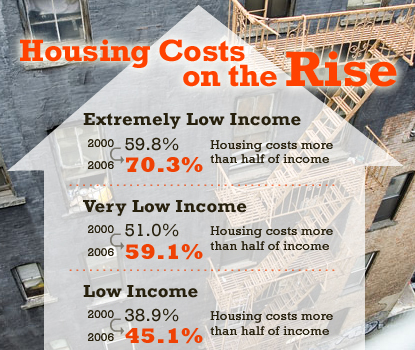

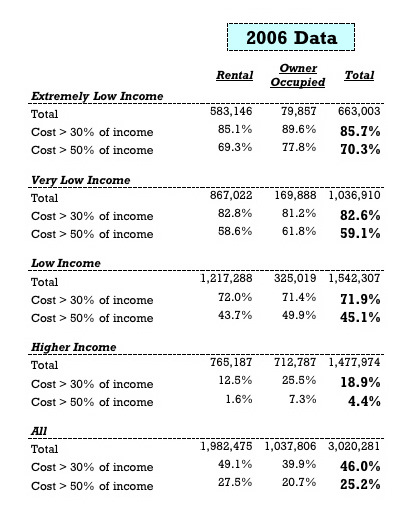

In 2000, 36.7 percent of New Yorkers lived in unaffordable units. By 2006, that the percentage had increased to 46.0 percent, which means that about 280,000 more New York City households now live in non-affordable housing than they did eight years ago. An analysis by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development using the 2000 Census showed that one fifth of New York City households then spent more than half of their income on income. By 2006 that had increase to almost one quarter. (More results are in the accompanying table below.)

These results were produced using the latest available American Community Survey data. I performed the same analysis that HUD had done for the 2000 Census. Of those New York households classified as low income, 71.9 percent lived in unaffordable housing, an increase from increased from 62.6 percent in 2000. The number of these less affluent households spending more than 50 percent increased from 38.9 percent to 45.1 percent during the same period. (The accompanying table has more detail.)

This can be attributed to a number of developments. The median house value almost doubled from 2000 to 2006, and many people stretched their budgets to buy in what they saw as a booming market. Rents at complexes such as Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village were increased to luxury levels, while many buildings left Mitchell-Lama moderate-income housing program. Meanwhile, it was reported last week that private companies are buying up inexpensive apartments in the hopes of converting them to higher priced buildings once the current tenants leave. With fewer and fewer rent-regulated apartments available, it is no surprise that an affordable apartment in New York City is becoming scarcer and scarcer.

The mayor's PlaNYC2030 for sustainable growth acknowledges the affordable housing issue. The plan expects a net increase of about 300,000 homes to accommodate the growth of the population from 2005 through 2030. To accommodate the housing needs, it outlines a series of steps, including a large number of residential “upzonings” to make it possible to build higher density housing than is now permitted in many areas in the city, housing within easy access to transit and an effort to create and preserve affordable housing using city land, subsidies, and incentives.

This is not the mayor's first attempt to address the housing crunch. The results from New Housing Marketplace to promote moderately priced homes brings into high relief just how difficult it is to make housing more affordable here. That plan calls for 165,000 units of affordable housing: about 73,000 preserved and about 92,000 newly constructed. After four years, the Independent Budget Office found that about 40,000 units were preserved and 24,000 units were new. At the same time, the city lost 280,000 affordable apartments and houses in the last six years. The challenge, according to the Independent Budget Office, is to build new homes affordable to low and moderate income households, as well as to middle-income households.

Unfortunately, Weiner is right. To create affordable housing requires subsidies and funding on a scale undreamed of since before the Reagan administration. The reason for this is obvious. Those most in need of affordable housing, cannot afford market rate housing. Yet, one can go only so far to use market rate housing to subsidize lower priced rate housing.

Density bonuses, set asides, 80/20 arrangements, etc., do help. But New York City need more than 1 million more affordable units along with significant efforts to make sure that the recent losses do not continue. There is little chance that the city, state or federal government will be willing to pay the bill for that. In the meantime, the search for affordable housing in New York will become more and more difficult, and more residents will abandon the search and move elsewhere or not even bother to come here.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â

A Religious City

When commentators discuss parts of the country where people hold strongly to religious beliefs and practices, they rarely include New York. In fact, for much of its history, people from the rest of the U.S. have tended to view the city as a godless metropolis in a largely god-fearing land.

The statistics, though, tell a very different story. If belonging to a religion translates to being religious, New Yorkers are very religious when compared to Americans as a whole. The proportion of people identified as adhering to an organized religion in New York City makes the five boroughs as religious as many places in the so-called "Bible Belt." Yet people here belong - and do not belong - to different religions than residents of other parts of the country.

An estimated 6.8 million New Yorkers - or more than 83 percent of the population -- were identified as being affiliated with some organized religion in 2000. This rate of adherents is higher than all the states except Louisiana - even slightly higher than Utah. (These numbers include those who were said to be affiliated with many different religious groups and were adjusted to take into account non-reporting and other factors.)

Since 1990, though, there seems to be some decline in religious affiliation in New York City. In 2000, three-fifths of all New Yorkers were reported as affiliated with one or another religious body and so were called religious "adherents." The number was down to 4.8 million from just over 5 million in 1990. (These are the unadjusted figures.)

| New York City | New York State | United States | |

| All Religions (adjusted) | |||

| Adherents | 6,682,139 | 14,366,781 | 173,046,520 |

| Rate | 83.44 | 75.71 | 61.49 |

| All Religions (Unadjusted) | |||

| Adherents | 4,783,779 | 11,459,836 | 141,364,420 |

| Adherence Rate | 59.74 | 60.39 | 50.23 |

The data used here are from the Religious Congregations and Membership Survey sponsored by the Association of Statisticians of Religious Bodies and distributed by the Association of Religious Data Archives. These data ask representatives of each congregation for the number of members they serve. Data on religious adherents was released February 1 and are available through www.socialexplorer.com Social Explorer and from the www.thearda.com Association of Religious Data Archives.

| Brooklyn | Manhattan | Queens | Staten Island | Bronx | |

| All Religions (adjusted) | |||||

| Adherents | 2,359,578 | 1,374,628 | 1,411,006 | 396,026 | 1,140,902 |

| Adherence Rate | 95.71 | 89.42 | 63.29 | 89.25 | 85.61 |

| All Religions (unadjusted) | |||||

| Adherents | 1,552,336 | 1,075,375 | 1,072,693 | 332,964 | 750,411 |

| Adherence Rate | 62.97 | 69.96 | 48.12 | 75.04 | 56.31 |

Looking at the whole metropolitan area, which includes 39 counties in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut, as well as Pike County, Pennsylvania, almost 79 percent of the population are adherents, making the metro area 31st out of 276 in terms of religious affiliation. Virtually all the metropolitan areas reporting a higher proportion are in the South, including Lafayette, Louisiana, with the New York City area having a higher proportion of adherents than the Salt Lake City or Little Rock area.

Furthermore, New York State is the fifth most religious state. Only Louisiana, Mississippi, Utah and North Dakota have a higher proportion of religious adherents.

At the other end of the scale, West Virginia, Maine, Nevada, Washington and Oregon have the smallest percentage of their populations identified as belonging to an organized religion. Between 35 percent and 40 percent of their residents are adherents, compared to New York State's 75 percent. Metropolitan areas in those states have similarly low rates of religious membership.

A Diversity of Faiths

Religious though New York City may be, its mix of religious, as with its mix of residents, differs greatly from the rest of the United States. New York City is much more Catholic (62 percent versus 44 percent) and much more Jewish (22 percent versus 4.3 percent) than is the rest of the United States.

While smaller in number, Muslims and members of various Eastern Orthodox churches also have more members proportionately in New York City than in the state or the country. For example, slightly more than 2 percent of New Yorkers attend mosques, compared to only about a half of 1 percent of all Americans.

Protestants are much less well represented among New York City's religious members. In New York City 4.2 percent of religious adherents belong to evangelical Protestant churches and 6.5 to mainline Protestant churches, compared to 28.2 percent and 18.5 percent, respectively, for the nation as a whole

The pattern of religions varies throughout the city. Manhattan, Queens and Brooklyn have a higher proportion of Jews and Muslims, while Staten Island and the Bronx are much more Catholic. Manhattan has the highest proportion of mainline Protestants, while Brooklyn leads in terms of Evangelical Protestants.

| Brooklyn | Manhattan | Queens | Staten Island | Bronx | |

| Catholics | 58.8% | 52.5% | 60.0% | 79.6% | 77.5% |

| Evangelical Protestant | 5.5% | 3.0% | 3.9% | 2.8% | 4.2% |

| Mainline Protestant | 6.6% | 9.3% | 5.7% | 4.3% | 4.7% |

| Jewish | 24.4% | 29.2% | 22.2% | 10.1% | 11.2% |

| Muslim | 3.7% | 3.4% | 4.9% | 2.4% | 1.6% |

| Eastern Orthodox | 0.7% | 1.8% | 2.7% | 0.6% | 0.5% |

| Other Religions | 0.2% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

Measuring Religion

The data presented here represent one method of measuring religion in the United States. Other measures, such as the American Religious Identification Survey estimate religion by asking individuals their religious identification.

Both approaches to measuring religion have some biases. However, the general patterns found seem to be the same. Both identify New York City and State as quite religious and the Pacific Northwest to be much less so. They also corroborate one another in terms of the patterns of religion identification and membership in the city. In the s religious identification survey, taken in 2001, about 13.4 percent of New York State residents did not identify with any religion. Estimating the number of people affiliated with any religion, though, particularly for Muslims and Jews, poses difficulties. The Census does not ask people about their religious affiliation.

To look at the figures for about 150 religious denominations by county and state, go to www.thearda.com or to www.socialexplorer.com A book was recently published that presented much more detail from the ARIS: Religion in a Free Market. Further analysis of data similar to that presented here can be found in The Churching of America, 1776 to 2005.

| New York City | New York State | United States | |

| % of Adherents By Group | |||

| Catholics | 62.0% | 65.9% | 43.9% |

| Evangelical Protestant | 4.2% | 4.9% | 28.2% |

| Mainline Protestant | 6.5% | 11.3% | 18.5% |

| Jewish | 21.9% | 14.4% | 4.3% |

| Muslim | 3.5% | 2.0% | 1.1% |

| Eastern Orthodox | 1.4% | 1.0% | 0.7% |

| Other Religions | 0.4% | 0.5% | 3.2% |

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Will the 2010 Census "Steal" New Yorkers?

Throughout the 1990s, New York City's population appeared to grow from about 7.35 million until it reached slightly over 8.0 million for the first time ever. Since then, growth continued, and by 2006 New York City was said to have somewhat in excess of 8.2 million people. As preparations ramp up for the 2010 Census, most would expect that that count will register New York City's continued gains. Yet when the Census numbers are announced, New York City's renewed growth could appear to have halted and even reversed -- not because fewer people actually live here but because of new Census procedures.

Censuses, including the ones in the United States, are really about two things: power and money. The main use of the count is to reapportion Congress and redraw lines for the state legislature and local government bodies. Simply put, every extra person in New York City (and by extension New York State) leads to extra power for the state and the city, and to additional government funds.

The growth in largely Democratic New York City in 1990s, as depicted by the Census, along with declines in population in more Republican areas upstate, led to a serious problem for the GOP-dominated State Senate. Instead of simply shifting some seats from Republican areas to Democratic ones, as the Census would seem to have indicated, the Senate tried to instead solve its dilemma by adding an extra seat to the body and forcing massive redrawing of lines in New York City, while keeping them largely intact in Long Island and upstate.

Counting More New Yorkers

While more people did live in New York City 2000 than in 1990, a large share of the growth in population recorded by the 2000 Census is due to the efforts of the Population Division of the Department of City Planning and its director Joseph Salvo. Indeed, perhaps half the growth can be attributed to their efforts to include formerly overlooked households in the Census and make sure they were counted. Some of these households were never reached, so the data on them came from their neighbors, with the Census Bureau filling in some of the blanks. Now the bureau headquarters in Washington is challenging the methods and approaches that led to New York City's surprising growth. In effect, it claims, some of the households counted do not actually exist.

For the 2000 count, the Census Bureau allowed local authorities to examine and update the local address file and add the following types of units:

- New construction

- Conversions of buildings from non-residential to residential use

- Garages converted to residences

- Attics or basements used as apartments

- Subdividing that yields apartments

The city planning department counted both doorbells and mailboxes to try to assess the many different types of conversions that had taken place. Many of these homes, of course, are illegal and do not have an official Certificate of Occupancy. Nonetheless, many people live in such apartments and should be counted. In 2000, the planning department suggested the addition of 439,069 additional housing units. The Census Bureau eventually accepted about 370,000 of these residences, including about 86,000 after an appeal by the city. The homes from the appeal alone would have added on the order of 200,000 to 250,000 New Yorkers to the Census.

Since 1960, the census has sent long forms, requesting more detailed information, to a certain percentage of homes. The 2010 Census will no longer have a long form. The questions that formerly were part of the "long form, are now administered yearly in the American Community Survey, which began in 2005 and first was released in 2006.

Beyond that change, the planning for the 2010 Census includes a much more restrictive definition of what constitutes a household. Indeed, Census staff suggests that if there is any question about how many units are in a given structure they will consult with the property owner, who very likely may have illegally divided it, to find out how many unites are "actually" in the building. Some landlords, of course, will be loathe to report their illegal units, and will deny their existence. Furthermore, there seem to be plans to send only one form to each address, even though there are many instances where two households share a mailbox. If these procedures are put into place, New York City could very well lose hundreds of thousands of population in the 2010 Census Count.

An Alternative Plan

Joseph Salvo suggests that the Census use a method called update and enumerate. In that method, questionnaires are not mailed. Instead Census workers walk blocks with a list of addresses in hand, knock on doors, update addresses and count residents. This method is used in other places, such as resorts and Native American reservations, where it is difficult to ascertain the number of households in a given area. In sections of Queens, Brooklyn and the Bronx, where there are many households and residents in some structures, such a method done properly would lead to a more accurate count than mailing forms.

The 2010 Census will be used for reapportionment and redistricting and population estimates, as well as providing the basis for all population reporting for the community survey in the coming decade. As such, its accuracy is vital for New York City and the share of power and money it will have both in the United States and in the state.

Unless New York City's special characteristics are taken into account, it is plain that the city will be a loser in the 2010 Census, as it was for decades and decades until 2000. We are lucky to have Joseph Salvo and his Department of City Planning team as our advocates. Without them, New York City would have never officially reached the 8 million made and in 2010 could turn out to be below it once again.

(The discussion of LUCA in the 2000 and 2010 Census is drawn from Joseph Salvo's presentation to New York Chapter of the American Association for Public Opinion Research, September 27, 2007. That presentation is available on the Web site. My presentation on the results from the American Community Survey is available here. Any opinions expressed are mine and mine alone.) Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â