Upstate And Downstate -- Differing Demographics, Continuing Conflicts

The court fight over funding for public education in New York -- in which a judge agreed that New York City’s schoolchildren were being shortchanged in favor of schools throughout the rest of the state -- is just the latest and most visible example of the old and bitter relationship between upstate and downstate (which means both New York City and its suburbs). New conflicts arise; old ones never seem to die.

A look at the regions’ differing demographics helps explain why this relationship continues to be so difficult.

Downstate Grows, Upstate Does Not

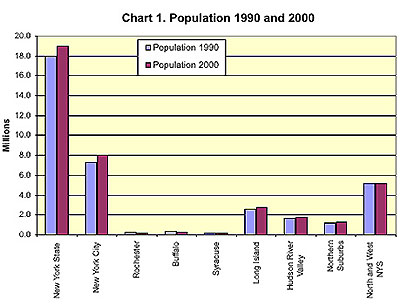

New York City's population accounts for almost half of the state. Throw in Long Island and the northern suburbs (Westchester, Rockland and Putnam) and downstate accounts for almost two-thirds of the state. New York City is the states only "first class city." It is joined by four 2nd class cities, Yonkers (just north of the Bronx), Syracuse, Rochester and Buffalo. The few hundred thousand population of each of these cities is dwarfed by the size of New York City and its suburbs.

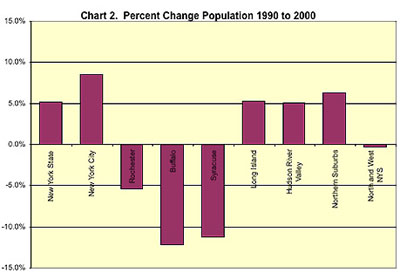

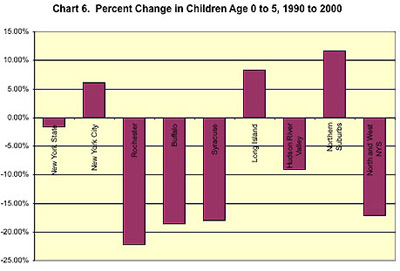

While New York City and its suburbs have been growing, the three upstate cities are hemorrhaging population, as is the entire region north and west of the Albany that contains them.

Largely this is due to the loss of the industrial base in Western New York State along with some redistribution of population from the old cities to the surrounding suburbs. These trends also affect the city and its suburbs, but newer economic opportunities in finance, higher technology and corporate headquarters offset the loss of industrial firms. These trends are unlikely to be quickly reversed. Western New York has been losing population for decades, and white and middle class flight to suburbs started even before World War II.

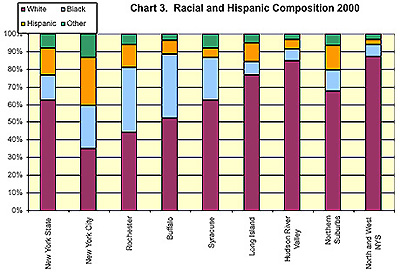

New York City is Diverse, the Suburbs and Upstate are Not

New York City is less and less like upstate New York and less and less like its suburbs. The racial and ethnic composition of the city is very different from the upstate cities, and even more different from the rest of downstate--the city's suburbs and the Hudson River Valley area.

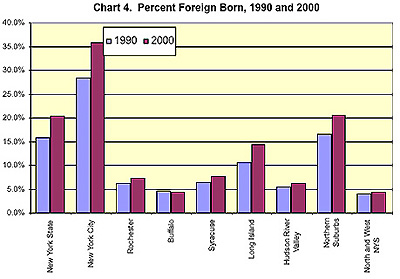

While foreign born residents flocked to the city and suburbs, they have not changed the composition of upstate New York in any substantial way. So though New York City shares the foreign born population with its suburbs, the city's racial and ethnic diversity is much greater than either upstate or the suburbs.

New York is a foreign and minority city with high paying industries such as the financial sector. The rest of the state consists of rural and semi-rural areas mostly inhabited by native-born whites, mostly white suburban communities, and some declining industrial cities.

Not surprisingly, the rest of the state is either jealous of New York City's economic prowess, or suspicious or hostile to its largely minority and foreign residents, or both.

Money and Children Matter

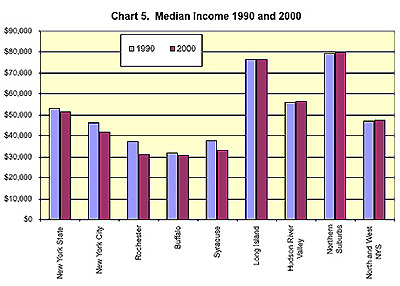

The differences and trends between the city, the suburbs and upstate affect the money available for the city and elsewhere to provide needed services. They also affect where services are needed.

Plainly, resources are not as readily available for any of the cities to finance services such as education, as they are in the suburbs or the Hudson River Valley area. The state does make up some of the funding gaps for the upstate cities, but New York City with more than 42 percent of the city students still waits for the resources promised by the Campaign for Fiscal Equity case. Meanwhile, the suburbs appear, in general, to have adequate resources.

The trends in young and new students mean declines upstate, and increases downstate, most particularly in New York City. In short, there are more educational needs and they continue to grow, in exactly those areas where resources that can be tapped to fund them are lacking. Even in the suburbs, the areas of high need and population growth (e.g. Yonkers) have few available resources. New York City depends the rest of New York State for its funding for needed resources. Its chance of success in getting these resources, even with a popular Republican mayor, seems very slim.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Four Trends That Shape The City's Political Landscape

The election of Antonio Villaraigosa as Mayor of Los Angeles encouraged Fernando Ferrer's campaign to rally Hispanic support. But it is not a strange kind of vanity that turned Michael Bloomberg into Miguel in some recent ads, as the billionaire's mayoral campaign started in earnest with television commercials in Spanish.

New York City is not like Los Angeles, where nearly 85 percent of all Hispanics are Mexican. There is a dizzyingly diverse mix of Hispanic immigrants in New York, and the various groups may not all respond to one ethnic appeal.

This diverse wave of immigrants to the city is one of four demographic trends that define New York City’s unique political landscape, all of which the candidates must understand, even if they have little power to change them.

Immigrant Waves

New York City's recent population growth was fueled by immigration. Without it, the city's population would not be near eight million. "Without the immigrants,” Mitchell Moss has said, “New York City would be Detroit," a city whose population is lower now than it was in 1930.

During the 1990s New York City continued to draw large numbers of immigrants with a variety of backgrounds, origins and economic status. Unlike virtually every other immigrant area in the United States, immigrants to New York City come from many different places:

- older European countries such as Russia, Italy and Poland;

- the Caribbean, including the Dominican Republic, Jamaica and Haiti;

- Asia, including China, Korea, Pakistan, Bangladesh and India;

- Central and South America, including Mexico, Ecuador and Colombia.

Some of these groups are better educated than others; some gravitate to the professions; some are self-employed. The economic status, family status and ratio of male to female vary widely from group to group. The immigrants in New York City today are much more segregated from the rest of the population and from other immigrant groups than were immigrants at the turn of the 20th century, and even groups from the same nation often gravitate to different locations.

Mayor Rudy Giuliani once remarked that he loved all immigrants, legal or illegal, but in recent years New York City, along with the rest of the country, has reversed that inclusive sentiment. After 9/11, the climate for undocumented foreign born, foreign students and foreign workers in New York City (as elsewhere) has worsened. Entering the country, either legally or illegally has become much more difficult, and undocumented immigrants have a harder time living here since they can no longer open bank accounts or obtain driver's licenses. It is possible that the immigrant waves have now slowed.

Racial Segregation and the Black Middle Class

The African Americans in New York City are highly segregatedfrom other groups. Within this segregation, there is a burgeoning black middle class in South Eastern Queens as well parts of the Northeast Bronx and recently the beginnings of one in parts of Harlem. Blacks in Queens have incomes at least on par with the whites living there, and the neighborhoods around St. Albans, Cambria and Laurelton are especially affluent and virtually 100 percent black. These areas contain highly mobilized and affluent potential supporters for any mayoral campaign. Many candidates have already recognized this constituency and sometimes visit the black churches in Queens on Sunday mornings in search of votes and contributions.

Rising Income Inequality

Areas of wealth exist around the boroughs, but New York City and especially Manhattan remain economically stratified with income inequalitydwarfing that of most third world countries. Neighbors and peers of Michael Bloomberg in the Upper East Side zip code of 10021 supplied the most political donations to both the Bush and Kerry campaigns in 2004 of any zip code in the country. The rich folks constituting the top 20 percent of Manhattan have about 50 times the income (over $350,000 on average) of the poor folks in the bottom 20 percent. Income inequality within the very small geographic area of Manhattan is a growing trend, and it seems there is little New York City can do about it.

Middle Class Exodus of People and Jobs

Many people of the middle and upper middle class are moving outside of New York City into the New York metropolitan area. The movement of people and jobs undoubtedly increased in the aftermath of 9/11, but the trend began in earnest after World War II, especially the more affluent who sought employment, housing, city services and improved quality of life outside of city limits.

New York City is increasingly the home of the foreign-born, as well as native-born African Americans and Hispanics. Such residents, in fact, are more and more in need of primary, secondary and higher education, decent health care, reasonable employment, public transportation, etc. While the wealthy take care of themselves and the middle class leave New York City, new residents and those on the bottom become the core recipients of vital city services and those most affected by changes to them. Yet, the city struggles to fulfill these needs, despite its disproportionate tax burden. The Campaign for Fiscal Equity school funding case, the abolition of the commuter tax, the crumbling city infrastructure and the big development plans both for Ground Zero and for the West Side contribute to the impression that New York City residents and their needs are subordinate to the interests of suburban and upstate residents.

It may not matter much whether Gifford Miller, Anthony Weiner, Virginia Field, Freddy Ferrer or Michael Bloomberg is elected, or which ethnic, immigrant or racial groups the candidates mobilize. New York City's needs will remain the same, and these same four trends will continue to shape the issues. Managing or overcoming the negative impacts of these trends will prove a daunting task for the next mayor, whoever that turns out to be.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

New York's Responders and Protectors

They stand apart, the 70,000 or so people hired to respond to crises in the city, protecting the lives and property of New Yorkers – police officers, firefighters, corrections officers, FBI agents, and so forth. To many, especially since September 11th, they stand apart as heroes. To some, they stand apart as villains. But, looking at statistics from the 2000 Census, they stand apart from the average New Yorker in other ways as well. They are, for example, whiter, less educated, less likely to live in the city, and also more affluent than the average New York worker.

The Numbers

According to the Census, and departmental websites, there were about 40,000 police, and 11,000 fire fighters (including supervisors, but not including civilians), who were employed by and work in New York City. The census also found about 8,000 local corrections officers, as well as 11,000 protectors and responders employed by the state or Federal government working in the city. These presumably include officers from the Port Authority, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Drug Enforcement Agency and other law enforcement agencies. There is substantial variation among these different workers, but, as a whole they are quite different from other city workers, including those who work in other agencies of local government.

Where They Live

About half the fire fighters, and two-fifths of the police, live outside the city, in areas very different from the neighborhoods they service. By contrast, one-sixth of other government workers and about one-fifth of all New York City workers live outside the city. As a result many more of the responders and protectors are more likely to own their own homes, be married and live with their spouses (firefighters especially) and drive to work.

|

Characteristics of New York City Responders and Protectors and Other Workers

|

||||||

| NYC Police | NYC Fire Fighters | NYC Corrections | State Federal Protectors | Other Local Government Employees | All Other Workers | |

| A. Live and Work | ||||||

| % Live in NYC |

60%

|

50%

|

73%

|

58%

|

84%

|

78%

|

| % Drive to Work |

77%

|

87%

|

74%

|

68%

|

48%

|

31%

|

| % Married with Spouse |

56%

|

70%

|

52%

|

55%

|

49%

|

47%

|

| % Homeowners |

68%

|

83%

|

68%

|

66%

|

52%

|

44%

|

| B. Sex | ||||||

| % Male |

81% |

99% |

66% |

79% |

42% |

55%

|

| % White |

71%

|

93%

|

38%

|

69%

|

49%

|

56%

|

| C. Background | ||||||

| % Hispanic |

19%

|

6%

|

16%

|

14%

|

18%

|

20%

|

| % Black |

19%

|

4%

|

53%

|

31%

|

34%

|

19%

|

| % Native Born |

90%

|

93%

|

84%

|

88%

|

70%

|

59%

|

| % Born New York State Born |

81%

|

87%

|

71%

|

69%

|

55%

|

40%

|

| % Irish Ancestry |

27%

|

46%

|

7%

|

20%

|

8%

|

9%

|

| % Italian Ancestry |

23%

|

31%

|

16%

|

17%

|

12%

|

11%

|

| D. Education and Income | ||||||

| % High School Grad |

99%

|

100%

|

100%

|

100%

|

94%

|

89%

|

| % College Grad |

26%

|

29%

|

14%

|

34%

|

48%

|

40%

|

| Median Age |

35

|

39

|

39

|

37

|

43

|

38

|

| Median Personal Income |

$54,200

|

$62,000

|

$52,000

|

$50,000

|

$35,000

|

$31,000

|

| Median Household Income |

$83,000

|

$84,000

|

$74,500

|

$80,000

|

$65,200

|

$65,400

|

Race, Gender, Ethnic Origin

Unlike other workers, they are predominantly male, virtually all male in the case of the fire fighters. A higher proportion of the responders and protectors are native born, and a large fraction were born in New York State. A lower proportion of the police and especially the fire fighters are black than other protective workers, and a lower proportion of the fire fighters are Hispanic. Perhaps, it is not surprising that many fire fighters wanted to wear Tam O'Shanters again this year in the St. Patrick's Day parade, since almost half claim Irish heritage. The police, the fire fighters and the state and federal protective workers are more likely to be Irish than workers as a whole. Police officers and fire fighters also are more likely to claim Italian heritage.

New York City's fire fighters are virtually all white and all male. Indeed, the United States Department of Justice recently launched an investigation into hiring discrimination in the department. Now the department plans to spend $1.4 millionto do something about it.

Education And Income

Though virtually all protective workers are high school graduates, a lower proportion than other city workers and other workers in general have completed college. The protective workers do earn substantially more than other local government workers, or city workers as a whole, and their households also are much more affluent. In terms of pay and benefits, the protective occupations are quite well paid, and it is not surprising they are sought-after positions.

Analysis Notes

This analysis was done by using the occupation, industry, employer and place of work codes for the individual records in the five percent Public Use Micro-Data Sample (PUMS)from the 2000 Census, which provides individual and household level data. All figures are based upon this five percent weighted sample. The New York City Fire Department and New York City Police Department can be distinguished in this manner. Obviously there may have been some changes since April 2000 however the number of police and fire fighters estimated by the Census sample is almost exactly what the two departments reported in that year.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â