The 2006 New York City Budget

|

Mayor Ed Koch saw a "rosy glow on the horizon" and proposed hiring 10,000 new city employees.

Mayor David Dinkins found money to put more cops on the street, extend library hours, and expand school health programs.

Mayor Rudolph Giuliani gave teachers a huge raise, handed out multiple tax cuts, and declared, "We have changed the direction of the city."

Each of these mayors was proposing a budget in a year (1985, 1993, and 1997 respectively) when he was running for reelection.

So in this election year, it was not surprising when Republican Mayor Michael Bloomberg's $48.3 billion budget played up the good news, downplayed the bad news, and blamed the $3 billion deficit on Albany.

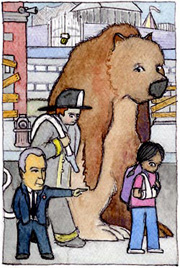

Two years ago in his budget presentation, Bloomberg was upfront about closing six firehouses. In this year's presentation, he neglected to mention that his new budget cut staff at 49 firehouses. And if it wasn't clear from this that his budget address was also a campaign speech, the mayor said, "Now is not the time to change course."

But campaign season is also time for the mayor's critics and opponents to warn New Yorkers that election year budgets are often followed by post-election budget problems.

|

WHAT'S IN THE MAYOR'S BUDGET?

The Good News

In contrast to his three previous budget plans, the mayor did not offer a "doomsday scenario" for what might happen if he did not get his way: He did not threaten to close zoos or shut firehouses or cut back on trash pickups.

In large part, that is because the city's economy is showing signs of recovery.

Tax revenues are back to pre September 11, 2001 levels. Wall Street profits - which account for about one-third of the city's tax revenues - are up. Commercial and residential real estate are strong. And tourism is at record levels.

"We are in better shape today than we were a year ago," the mayor said. "My message is one of cautious optimism."

But some argue the mayor is relying too much on a good economy.

"You can't just say we are going to grow our economy out of these problems," said Republican Councilmember James Oddo. "What will happen is that when Wall Street goes in the tank, which it does from time to time, there will be two choices: close every firehouse in the city or raise taxes."

The Deficit

Despite the good news, the city's budget has a structural imbalance: Year after year, expenses continue to be higher than tax revenues.

In 2006, the city expects to have a $3 billion deficit.

In order to close the gap, the mayor plans to:

- Use a $1.4 billion surplus from this year to fill the gap in next year's budget.

- Cut $600 million from the city's current programs.

- Receive $500 million in aid from the state government in Albany.

- Receive $250 million in aid from the federal government in Washington.

- Save $325 million in changes to pension and health insurance.

The mayor argues the deficit is not entirely his fault and that the amount of money the city spends on services like police, firefighters, and sanitation has only increased about six percent over the last five years.

The most significant problem, Bloomberg argues, is with so-called "non-discretionary" expenses - things like Medicaid payments, pensions and benefits for city workers, and payments on debt from past - that the city cannot control.

The cost of these four items now total more than $20 billion a year, almost 40 percent of the city's entire budget. As a result, the city faces another estimated $4.4 billion deficit in 2007.

"The city is no longer in control of its biggest expenses," the mayor said.

Some criticize the mayor for not doing more to deal with these issues.

"So are we heading for two-thirds or three-quarters of the budget being out of the mayor's control?" said Diana Fortuna of the Citizens Budget Commission. "You have to start to attack the source and get cooperation from Albany, which is never an easy thing, and cooperation from labor unions."

The Cuts

The mayor's plan calls for nearly $600 million less money for city agencies that deliver the services that New Yorkers depend on everyday, but he refused to call them "cuts."

"We are not cutting programs," Bloomberg said. "We are doing more with less."

However, the City Council argues that they are cuts and that they will be painful for New Yorkers.

The mayor's cuts include:

- Reducing staff at 49 firehouses

- Shorter library hours

- Cutting $15 million from after-school programs

- Eliminating some hot meals to homebound senior citizens.

The City Council's biggest criticism of the mayor is with his capital budget, which proposes cutting $1.3 billion from school construction over the next five years.

"We are talking about libraries, science labs, playgrounds, and bathroom repairs," said Councilmember Eva Moskowitz, who chairs the council's education committee. "The `Education Mayor' is clearly not putting children first."

Tax Rebate

Despite the deficit and budget cuts, the mayor is planning on again giving out a $400 property tax rebate to each owner of a co-op, condo, or private house who had to pay the 18.5 percent property tax increase imposed in 2002. Business owners and landlords of large buildings would not be eligible.

The tax rebate will cost the city about $250 million. The mayor said he would likely give out the tax rebate again next year as well.

City Council Speaker Gifford Miller, who fought the mayor on the tax rebate last year, but eventually accepted the idea, said it was "too early to tell" if the $400 rebate makes sense. "We need to look at it in the context of the whole budget," he said.

Since the city does not have the power to raise or lower taxes (with the exception of property taxes), Mayor Bloomberg is also lobbying Albany for some changes in when certain taxes will expire.

Governor George Pataki has proposed ending the personal income tax surcharge - a state tax on the top two income brackets - retroactively to December 31, 2004, which the mayor opposes.

Two years ago, the state reinstated taxes on clothing and shoes that cost less than $110. That sales tax is also set to expire this summer, which the mayor supports.

|

WHAT THE CITY WANTS FROM ALBANY

Mayor Bloomberg's budget assumes that the State Legislature in Albany will give the city $500 million.

"We send $11 billion more to Albany in tax revenue than we get back," the mayor said, "So I think asking for $500 million is reasonable."

One of the biggest priorities is Medicaid reform. Unlike most other states, New York requires local governments to pay a major portion of the Medicaid bill. New York City's costs have risen dramatically in recent years, and will cost the city nearly $5 billion in 2006.

If the state enacted the Medicaid reforms the city is asking for, it could save the $425 million next year.

The city has also assembled a long list of other ways the state could help, including:

- Repealing the Wicks Law, which requires the city to hire multiple subcontractors for building projects (which the city calculates is worth $451 million)

- Reforming Social Security reimbursements (worth $130 million)

- Allocating funds to upgrade voting systems (worth $92 million)

- Enacting tort reform (worth $83 million)

- Giving the city permission to use red-light cameras (worth $13 million).

In addition, the mayor is fighting a series of proposals in the governor's budget that would increase tuition at the City University of New York, delay funding for Family Health-Plus programs, and provide $2 billion less for mass transit projects than the Metropolitan Transportation Authority has requested.

City Council Speaker Gifford Miller said the mayor must try a new approach if he wants to get real results from Albany.

"He keeps going back to the same playbook and we keep getting the same results," said Miller. "We need to get tougher and to fight harder."

|

WHAT THE CITY WANTS FROM WASHINGTON

The city is also asking the federal government for $250 million in aid in order to balance its budget.

One way the city hopes it gets help from Washington is in Homeland Security funding. New York officials have long complained that the formula for giving out security money shortchanges the city, which has a higher level of risk than rural areas. If the formula is changed in the way the city hopes, it could save $200 million next year.

The city also presented a list of other options, including:

THE UNKNOWN RISKS

There are a number of issues that the mayor's budget does not address that critics say could end up costing the city hundreds of millions of dollars and make the whole document meaningless.

One major issue is school funding for the Campaign for Fiscal Equity lawsuit, which requires more funding for city schools.

In November, a court-appointed panel recommended that city schools should receive an additional $5.6 billion a year phased in over the next four years. For next year, the panel recommended an increase of $1.4 billion, but did not say how much should come from the state and how much should come from the city.

If the city's funding equals nearly a quarter of the money, it will have to pay an additional $330 million next year and a total of $1.4 billion by 2009.

The city is also negotiating contracts with nearly half of the city's workforce, including firefighters, police, and teachers.

Nearly $1 billion of the mayor's plan is based on the assumption that the unions will agree to the city's offers, which each union has already rejected.

"The mayor says that paying cops a fair wage will cause the city pain," said Randi Weingarten, head of the municipal labor coalition. "No wonder so many average New Yorkers believe the mayor is out of touch."

THE BUDGET ROAD AHEAD

The "preliminary budget" Bloomberg presented last week is the starting point for the annual budget process. The mayor will present a revised "executive budget" in April. By law, the administration and the City Council must agree on a balanced budget by June 30.

Historically, the two sides will reach an agreement after fighting over about $500 million out of the $48 billion budget - and both sides will claim victory.

However, since it is an election year, each of the mayor's opponents is also taking aim at the plan.

Former Bronx Borough President Fernando Ferrer said a third of the money that the mayor plans to spend to build a new stadium of the Jets could fund "an after-school program in every middle school in the city."

U.S. Rep. Anthony Weiner called the $400 property tax rebate "the ultimate election-year gimmick."

Manhattan Borough President C. Virginia Fields predicted that because of unresolved labor contracts, Medicaid costs, and the need for more school and transportation funding, the budget "will balloon beyond what the mayor outlined."

"This is a different account than the rosy picture painted at the State of the City address and his `City of Opportunity,'" said Councilmember Charles Barron. "Opportunity for whom? Not for libraries, not for youth services, and not for education where schools have to be fixed up."

RELATED LINKS:

Governor George Pataki's Budget Address

Mayor Michael Bloomberg's testimony on proposed state budget

Gotham Gazette's 2003 NYC Budget Game

Â

Insurance And Its Threats In NYC

|

When Eliot Spitzer accused the world's largest insurance broker of fraud last fall, Joseph Belth, editor of trade publication Insurance Forum, described it as "the most important thing that has ever happened in the insurance industry in the history of the industry."

Many New Yorkers might be hard-pressed to name any other event at all in insurance history, aside from their own fender-benders and eye examinations.

But despite its low profile, the insurance industry is an important part of the economy, with insurers collecting trillions of dollars in premiums and providing millions of Americans with jobs. Insurance is also remarkably central to the lives of virtually every American.

Belth sees the New York State Attorney General's investigation as so significant because of the potential it has to change the way this vast industry works. Some see this potential for change as a way to combat a threat - widespread corruption that is forcing customers to pay significantly higher premiums. Others see Spitzer's investigation itself as the threat.

These are not the only threats the insurance industry feels. If insurance was devised as a way for both individuals and the community at large to reduce risk, insurance itself is at risk these days in a number of ways.

|

HOW INSURANCE WORKS Broadly defined, insurance is a way to reduce risk. The insurance industry itself is split into two categories defined by the type of risk handled: The first category is life and health - providing those who are injured help with medical expenses, and the families of those who die with economic security; the second is property and casualty - reducing the financial risk of a variety of other activities. Property and casualty covers a lot of ground. A partial list of types of insurance in the book The Invisible Bankers by Andrew Tobias, a book explaining the insurance industry, includes: protection for property damaged in floods, fires, or bridge collapses; losses stemming from riots, ransoms and political upheaval; and malpractice insurance for everyone from doctors to animal trainers to members of the clergy. For a certain price, insurance can be bought to protect against almost anything. Certain types, though, are legally required, such as auto insurance for those who want to drive a car, or property insurance for those who want to take out a mortgage. Some insurance premiums are collected automatically and handled by the government, like social security - which protects against poverty in old age, or unemployment insurance - which protects against poverty for those in between jobs. All of this is big business. American insurance companies collected over $1 trillion in premiums in 2003, employing 2.3 million people to sell and handle these lines. About two percent of American jobs are in the insurance industry. |

JOB LOSS: A THREAT TO THE ECONOMY

New York City's insurance industry has lost almost 10,000 jobs since 1997, part of a nationwide trend for financial industries to move as much of their operation as possible out of high-cost areas. Insurance is among the three financial industries that the city has traditionally relied heavily upon. The others -- Wall Street and real estate -- are bigger and more high-profile in New York, but insurance is still big business in the city: The headquarters of four of the country's top 10 insurance companies (based on revenue in 2003) are located here. This "FIRE" sector of the economy (for Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate) provided the city with 434,000 jobs in 2003. While they are less of a driving force than in the past, these industries still figure significantly in the city's economy.

Many of the insurance industry jobs leaving New York go to other places in the United States. Since at least 1990 the national insurance industry has continued to expand overall while contracting in urban areas like New York.

Other jobs have gone overseas. Spitzer believes some are doing so to avoid regulations. "There is, I would suspect, a Pandora's Box that should be opened so we can understand what is going on in these offshore venues," he told Congress late last year. "It will not be a pretty picture."

But the main reason that such jobs are leaving New York is economic: real estate and labor costs are much higher in New York than they are elsewhere. Better communications technology has made it easier for companies to take advantage of these differences.

Since the gaps in expenses are unlikely to be reversed, some say that New York should accept the loss of back office operations, while focusing its energy on encouraging companies to keep their core activities in the city.

"Our strategy - because we do now have an economic strategy -- is to continue to attract the front office headquarter functions," said Kathryn Wylde, head of New York City Partnership, a business group based in the city.

TERRORISM: A THREAT TO BIG BUSINESS

Most New Yorkers can conceive the serious threat posed to the city by terrorism; fewer have considered how the insurance industry has been affected by this threat.

September 11 cost New York City $80 billion. Of that, about $40 billion was offset by payments from insurance companies. These insurance payouts amounted to the largest loss in the industry's history - double that from Hurricane Andrew in 1992, the second costliest event.

Insurance companies felt forced to reexamine the way they do business. Before 9/11, terrorism insurance was generally covered as part of commercial property insurance without extra charge. But the attack made insurance companies see terrorism as a new type of risk. Because terrorist attacks are very hard to predict, and because the losses can be so high, insuring against it is expensive.

"There has been a fundamental change in the nature of risk in our society," wrote the Insurance Information Institute.

The burden initially fell on those who have to buy insurance for commercial property: some had trouble finding any insurance at all. For those who could, the average increase in costs in the year after the attack was 73.3 percent, according to the city comptroller's office. The owners of the Empire State Building, for example, were suddenly faced with a $9 million annual premium - nine times what they paid beforehand. For that, they actually got less coverage.

In response, the federal government passed the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act in November 2002. This law required that commercial property owners be offered insurance that protected against losses due to terrorism. In return, the federal government agreed to back up the finances of insurance companies in case of attack. Insurance prices dropped; coverage became more widely available.

But the law is intended to be a temporary solution - it expires at the end of 2005. Those who buy and sell commercial insurance have been lobbying for an extension, but Washington does not seem prepared to pick up the issue immediately. Since insurance policies are generally written in one-year spans and since the expiration of the federal guarantee is less than a year away, many see some disruption in business activities looming.

If a company does not have terrorism insurance, then it will have to pay for all damages it suffers from a terrorist attack. This could cause companies to balk when it comes time to expand or move operations to the city, says New York City Partnership economist Jonathan Schwabish, author of a recent report on terrorism insurance in New York City (in pdf format). Banks are also much less willing to lend money to companies that have not covered their risks.

"This could have ramifications beyond just companies being on the hook for their buildings if an attack did occur, " warned Schwabish.

AUTO INSURANCE PREMIUMS: A THREAT TO CONSUMERS…IN BROOKLYN

Phony car accidents are common in New York. In order to collect money from insurance companies, people stage crashes, cause crashes and even file claims for crashes that never happened. Phony medical offices established solely to treat non-existent injuries are so commonplace that they now have their own business category - "Doc in the Box" clinics. (Read Auto Insurance Fraud: Driving Rates Up In Brooklynby Mark Peters.)

There were about 800 indictments statewide for auto insurance fraud in 2003. Cases were concentrated largely in New York City's outer boroughs: the Bronx, Queens, and, above all, Brooklyn. In one 2003 case in Brooklyn, 567 people were arrested for running an operation that allegedly collected $48 million in fraudulent claims over several years. One member had been in over 1,000 car accidents.

The New York State insurance industry pays about $1.4 billion to pay for fraudulent claims annually; $500 million in Brooklyn alone. Insurers, in turn, pass the costs on to policyholders. In the United States, the average driver pays $817 to fully insure a car for a year; the average New York State resident pays $1,161. In Brooklyn the same policy can cost over $4,000.

Auto insurance fraud is not solely a local problem, nor is it a particularly new phenomenon. But New York State's system of no-fault insurance, which ostensibly prevents frivolous lawsuits, has proven very susceptible to being ripped off. For claims under $50,000, no-fault insurance calls on companies to quickly pay out without establishing blame, leaving them little leeway to investigate fraud.

Increased enforcement over the last few years have begun to address the probem, say public officials and industry representatives.

"The situation has improved dramatically from what it was two or three years ago when New York was without doubt the auto fraud capital of the United States between 2000 and 2002," said Robert Hartwig, chief economist at the Insurance Information Institute. Hartwig said that New York's higher costs will always keep insurance rates relatively higher compared to other states, but that enforcement was bringing it more in line with the rest of the country.

A task force appointed by Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz, however believes fraud is not the only problem that needs to be addressed.

"There must be a drastic revision of the entire auto insurance system if underserved and over-priced areas like Brooklyn are to have access to the affordable coverage that others around the state and country take for granted," a recent report by the task force read.

The insurance industry, the task force found, is practicing a subtle form of redlining, or restricting access to insurance based on location. Insurance companies base their rates on various criteria determining risk. Because insurers do not make these criteria public, some suspect that discrimination based on race, income, or the place where a person lives makes it harder for people with good driving records to get reasonably priced insurance.

"There's some concerns about racial and ethnic discrimination," said Jim Brennan, a State Assemblymember and the primary author of the report. "That people's real driving histories are not being taken into account."

ELIOT SPITZER: A THREAT OR A SOLUTION?

Parts of the insurance industry, said Eliot Spitzer, operate as "a secret cartel based on hidden payments and preferential treatment. As with any cartel, this results in higher prices for the public and a drag on the economy."

The obvious implication is that, by breaking up the ring, the insurance industry will become more efficient and, eventually, cheaper. But while Spitzer and his supporters see his work as a way to address a serious threat not only to a particular industry but to the nation's economy, some in the industry worry about what the end results of the investigation will be.

Secret Payments and Outright Fraud

Spitzer's investigation began with Marsh & McClennan, the world's largest insurance broker. Marsh's clients are corporations who need a lot of insurance. These companies hire Marsh & McClennan to consider offers from various insurers and find the best deal. While brokers ostensibly represent the buyer, Spitzer found that Marsh was also taking secret payments called contingency commissions from the insurance companies themselves. These payments are not illegal -industry groups defend them as necessary in many cases - but the investigation has questioned whether they raise conflicts of interest.

At Marsh, these payments were the determining factor in the broker's decision about which companies to send its clients to. To preserve the appearance of a competitive process, Marsh asked several insurers to enter bids that were higher than the one of the company to which it wanted to steer the business. This practice - called bid rigging - is a crime.

Spitzer has charged several others with similar collusive behavior, including insurance giants Met Life and AIG. His investigation has definitely shaken the entire industry, even if many say such practices are an exception, not the rule.

Is There Widespread Corruption in the Insurance Industry?

For those directly implicated, the consequences have already been rough. In the quarter after Spitzer made his findings public, Marsh & McClennan's net income dropped to $21 million, from $357 million the quarter before. It has subsequently laid off 3,000 workers - five percent of its total workforce. The company's CEO and five members of its board have also departed.

But insurance types are quick to claim that the practices taking place among several large companies are isolated incidents, and that industry-wide business do not need to change much.

"The people who are engaged in that activity should be prosecuted because it imputes the integrity of everybody else in the business," said Bernard Bourdeau, president of the New York Insurance Association, a trade group. "There are a few bad actors, and hopefully Spitzer got them."

But Spitzer has indicated that the public revelations he has made are not yet finished. Without saying so explicitly, he has hinted that those handling personal lines of insurance have been involved in many of the same shady practices.

Whether or not such charges turn out to be true, most people following the current investigations believe that there will be reform of certain practices within the industry. They disagree on how much is likely - or appropriate.

Will The Industry Reform?

Spitzer sees a major parallel the bad behavior he has uncovered in the insurance, financial securities and mutual fund industries.

"In each of these three story lines, there has been an abject failure of self-regulation," Spitzer testified at a congressional hearing. "Nobody came forward to say there is a problem."

New York, along with many other states and the federal government, is considering regulations that will better prevent such behavior. Many insurers resent this idea, describing Spitzer as more concerning with his own political image than with creating effective regulations.

"Filing lawsuits that significantly reduce the market value of individual corporations and entire industries - damaging millions of consumers and tarnishing the reputation of the vast majority of ethical business professionals in the process - is not my idea of consumer protection," said Ernst Csiszar, president and CEO of Property Casualty Insurers of America, who has also been the head insurance regulator of South Carolina.

But Robert Hunter of the National Insurance Consumer Organization believes that by drawing attention to the industry, Spitzer brings pressure on insurers to be more careful about their own practices; his investigation should also slow aggressive pushes for deregulation. Both of these things, believes Hunter, will ultimately lead to lower rates.

The question of whether reform is needed and whether reform will happen are not necessarily the same thing: the insurance industry is a historically powerful political force, effective in preventing being regulated in ways it doesn't like.

Some, including New York State's outgoing superintendent of insurance Greg Serio, hope that Spitzer's investigation gives enough push to overcome that barrier.

"The industry has earned a sweeping reform," he said.

ADDITIONAL READING

Insurance Industry Information

Insurance Information Institute

Wikipedia Entry on Insurance

Insurance Forum

Terrorism and Insurance

September 11: One Hundred Minutes of Terror that Changed the Global Insurance Industry Forever (by the Insurance Information Institute)

9/11 Sparks Dramatic Increase In Commercial Insurance Premiums In New York City (by the New York City Comptroller's Office)

Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (by the US Treasury)

New York City and Terrorism Insurance in a Post-9/11 World(by the Partnership for New York City)

Auto Insurance

Auto Insurance Fraud: Driving Rates Up In Brooklyn(Gotham Gazette article by Mark Peters)

Driving Force: The role of lawsuits in pushing up the cost of car insurance in New York State (by the Public Policy Institute of New York State)

Putting the Brakes on Out of Control Rates: An Examination of Brooklyn’s Record High Automobile Insurance Rates and How They Can Be Reduced(by the Brooklyn Borough President's Task Force on Equity in State and Local Policy)

Eliot Spitzer's Investigation

Timeline of the Investigation (by the Insurance Information Institute)

What are Contingency Commissions (by the Insurance InB?Ûõation Institute)

Social Service Programs Cut; Minimum Wage Raised

In the $105.5 billion budget that Governor George Pataki has proposed to the state legislature, he seeks to close the $4.15 billion gap projected for the next fiscal year by making deep cuts in health care for the state's poor, by raising tuition for state and city colleges, and, as the New York Times explained, by "giving New York City only a fraction of the education aid a court-appointed panel said it deserved by next year."

But the news already had been bad for New Yorkers with low incomes. In the current fiscal year (which ends on March 31), Pataki had cut some $100 million in state aid to New York City (plus federal matching funds) for programs that serve a cross-section of needy New Yorkers. These cuts were "among the steepest made to social services in about a decade,"according to the New York Times, and the people they are affecting include:

- adults on welfare who need preparation for job hunting;

- substance abusers seeking rehabilitation;

- people with mental illness who need treatment to stay out of institutions;

- the elderly;

- veterans;

- children at risk of abuse and neglect, or growing too old for foster care;

- high school dropouts trying to earn diplomas;

- homeless and runaway teenagers;

- students at state and city colleges;

- homeless adults and children;

- prison inmates preparing to re-enter society; and

- people with disabilities trying to go back to work or survive on Supplemental Security Insurance.

These were programs that the governor cut, the state legislature restored, and the governor vetoed.

One item added to the budget by the legislature was not vetoed by the governor: a $200 million lump sum for "member items" and "legislative initiatives". In the past, Pataki has vetoed similar unspecified appropriations, claiming that they were unconstitutional. They are distributed outside of the usual rules for government spending; no formal competition is involved. Individual legislators choose their own priorities, which may not coincide with the legislature as a whole. Still, "It's some of the only money we can count on to keep some of these programs alive," says Ron Deutsch of the Statewide Emergency Network for Social and Economic Security, otherwise known as SENSES.

Federal Spending Cuts Also Ahead

The federal spending bill covering most human services for 2005 is also a disappointment to many. Housing assistance for the elderly and people with disabilities will be reduced, as well as programs serving the poor. There will be less money for job training for youth, and too little energy assistance to meet the increased need caused by sharply higher fuel costs. While AIDS relief worldwide will increase, the nation will spend less on HIV prevention within the United States.

Some programs are benefiting under the federal spending bill. Funding will rise for the nutrition program for Women, Infants and Children, and for grants from the Compassion Capital Fund, which supports services delivered by religious and other charitable organizations.

Budget Reform

Late last year, the governor vetoed a budget reform bill, which was trying to make sure that the state budget would be passed on time for the next fiscal year (which officially begins on April 1); it has been late for each of the last 20 years. This is not an abstract problem for social service providers. The longer it takes to settle the budget, the longer service providers must juggle loans and reserve funds, trying to keep programs alive until their funding future is decided. Reducing uncertainty would make it easier for providers and their clients to plan for the future. A new bill proposed by the State Senate would put a specific contingency budget into effect if a regular budget has not been adopted by the start of the next state fiscal year on April 1. Advocates preferred the previous bill. In any case, this watered-down one is unlikely to gain support in the Assembly.

Minimum Wage Raised Over Pataki's Opposition

For the first time in three decades, the minimum wage in New York State is higher than the federal minimum. At the end of 2004, the State Senate overrode the governor's veto of a minimum wage increase, as the Assembly had done the previous August.

As of January 1, 2005, the hourly wage for most of the state's lowest-paid workers rose from $5.15 to $6. In 2006, they will get a raise to $6.75, and in 2006, to $7.15 an hour. An even lower minimum wage applies to restaurant and bar employees who earn tips. Their hourly wage, which was $3.30 an hour, is now $3.85, and will rise to $4.60 by 2007.

New York City has about 274,000 minimum-wage workers, according to the Fiscal Policy Institute(in pdf format). Most work in stores, restaurants, hotels, and similar businesses. Another 218,000 workers earn only a little more: $7.15 to $8.15 an hour. Economists believe a spillover effect raises the wages of such workers as well when the minimum wage goes up.

The governor vetoed the minimum wage bill in July, citing his preference for a nationwide increase. Currently, New York's neighboring states have a variety of minimums. New Jersey and Pennsylvania remain at the federal level of $5.15. Connecticut's minimum is $7.10 an hour, and Massachusetts and Vermont each have a $6.75 minimum.

A mother working full-time year-round, at the $5.15 minimum wage, can earn only $10,712 a year, which is below the federal poverty line if she supports a child. The $7.15 hourly wage will raise her annual wage to $14,872, almost enough to lift her out of poverty if she has two children.

The federal Bureau of Labor Statistics recently reported that the average hourly wage in each of the city's five boroughs ranged from $16.48 in Staten Island to $47.83 in Manhattan.

Linda Ostreicher, a former budget analyst for the New York City Council, is a freelance writer and consultant to nonprofits.