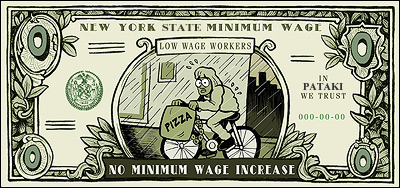

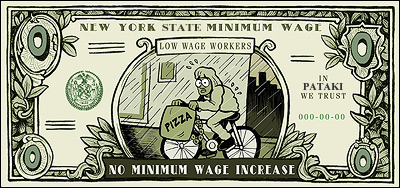

A Minimum Wage Increase Will Hurt Small Business and the Working Poor

The issue of increasing New York State's minimum wage is again receiving considerable attention in the state capitol in Albany. And at first blush, a lot of New Yorkers stopped on the street would probably agree with the general idea of putting more money into the pockets of the working poor. Even small-business owners may well think that putting more money into the hands of their poorer customers is a good idea. But raising the minimum wage is not the same as delivering more income into the hands of people with low-skill jobs.

The issue of increasing New York State's minimum wage is again receiving considerable attention in the state capitol in Albany. And at first blush, a lot of New Yorkers stopped on the street would probably agree with the general idea of putting more money into the pockets of the working poor. Even small-business owners may well think that putting more money into the hands of their poorer customers is a good idea. But raising the minimum wage is not the same as delivering more income into the hands of people with low-skill jobs.

In fact, it is a complicated issue with many potentially serious implications for the future of our state as well as our lowest-skilled workers. So, when something like a hike in the minimum wage is proposed -- something that sounds simple, intuitive and benevolent -- responsible citizens should still take a step back and ask: Who really pays for the increase? The answers may surprise you.

In 1999, New York hiked the state minimum wage to $5.15 per hour and permanently tied it to the federal rate. This placed New York State on par with every other state that links its minimum wage to the federal wage and eliminated the problems caused when competing states have differing wage laws. It leveled the playing field and placed the issue of a minimum wage where it belongs -- with the federal government.

Nevertheless, organized labor is now pushing hard for a $1.60 -- or 31 percent -- increase in the state's minimum wage, notwithstanding the competitive disadvantages for business that would come from leapfrogging the federal rate.

A higher minimum wage puts strong upward pressure on the entire wage structure, which is the real reason that unions support it. But as any first-year economics major will tell you, if you tax something (in this case, jobs) or increase its cost, you end up with less demand for that thing. Can a state with one of the most expensive business climates in the nation, that has 300,000 unemployed and has lost 100 manufacturing jobs a day for the past five years, afford a new round of generalized wage inflation? The unions ought to think this through more thoroughly.

Perhaps most surprising, though, is big labor's indifference to the question of whether or not a hike in the minimum wage would really help the working poor and whether we can afford its wider social and economic impacts. Research from Michigan State University, for example, found that increases in the minimum wage encourage more teenagers to leave school and enter the workplace, displacing lower-skilled workers from their jobs.

Raising the minimum wage will work to deprive the working poor of job opportunities. Those most affected will be single parents, developmentally disabled persons, school dropouts and recent immigrants with poor language and reading skills. If you price entry-level labor higher than its real value, jobs will not be available for people whose skills are limited.

Then there is the impact on small businesses, considered by many to be the engine of growth and opportunity in the American economy. A small increase of $1.60 per hour would cost a bake shop with ten clerks and bakers over $30,000 per year, not counting the increases that a higher payroll brings in the costs of workers compensation insurance, unemployment insurance, Social Security taxes, Medicare taxes and even liability insurance in some cases. This is money that most small employers simply do not have. So, what will they do? Lay off workers, increase prices, or both.

When you consider that businesses with fewer than 100 employees create the majority of new jobs in New York, and that small business has created about two-thirds of the net new jobs in the United States since 1970, the proposal to hike the minimum begins to look less attractive.

Small businesses in New York are struggling against a tide of steadily rising costs. To reverse this trend and stimulate growth and jobs we must work to reduce the costs of doing business. Increasing the minimum wage at a time when we can least afford it just adds to the problem.

Now, is the sky going to fall if New York increased its minimum wage? Would we see dramatic layoffs and skyrocketing unemployment overnight? Probably not. But given that state spending, debt and taxes are already too high, the increase would hurt.

The final reason for opposing an increase is that it is not necessary. New York offers a wide array of generous programs, like the Earned Income Tax Credit, that provide cash assistance to encourage people to work without the negative impacts of a hike in the minimum wage. Other assistance comes from the Child and Dependent Care Credit, the federal Child Tax Credit, the Home Energy Assistance Program, and the Real Property Tax Circuit Breaker. Health benefits are provided through programs like Child Health Plus, Family Health Plus, Healthy NY and Medicaid. Nutritional assistance comes from Food Stamps, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (popularly known as WIC) program, and school breakfast and lunch programs. A college tuition tax credit also aids low-income families.

In 2003, the state and federal earned income tax credit was worth $5,465 per year for New York families making no more than twice the poverty level, providing over $700 million to the state's working families and individuals. With the tax credit counted, the effective hourly wage for a single parent with two children is $7.77 per hour (well above the wage rate sought by the Working Families Party). Add in the value of food stamps, free school meals and health insurance and the effective value of a minimum wage job tops $14 per hour.

New York today generously helps its most needy residents -- and in ways that do not damage small businesses or destroy job opportunities for teens and low-skilled people. Goodwill toward those who are less fortunate than us is natural -- but it should not cause us to turn off our minds and end up spreading far more ill than good.

Mark Alesse and Matthew Guilbault are with the New York chapter of the National Federation of Independent Business, a nonprofit, nonpartisan group representing 20,000 small businesses in New York.

#####

Related Story

New York Workers Need A Raise

by Andrew Friedman and Fernando Ferrer

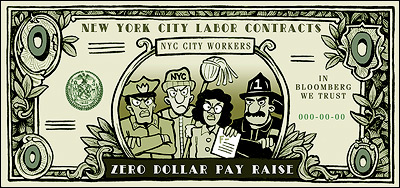

The City Budget and Labor Unions

When Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced last month that New York City's fiscal crisis was beginning to subside, he hailed the "heroes of this crisis" and said it was time to reward those who helped "get us through the last two years."

When Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced last month that New York City's fiscal crisis was beginning to subside, he hailed the "heroes of this crisis" and said it was time to reward those who helped "get us through the last two years."

But the "heroes" the mayor was talking about were not the police who saw their ranks decline by 4,000 officers nor the firefighters who worked to cover more neighborhoods after six firehouses closed - but taxpayers who own their own homes.

In his $45 billion budget, Mayor Bloomberg proposed a $400 property tax rebate for condo, co-op, and homeowners, but he said there was no money for pay increases for city employees.

"People will look and say there's lots of money in there for raises," the mayor said. "There isn't."

Every city labor union contract has expired, but Mayor Bloomberg says there can be no salary increases without concessions on work rules, benefit packages, and overtime and vacation policy. So far, the City Council, which has traditionally championed city workers, agrees with the mayor, and even offered to give out larger tax breaks rather than advocate for raises.

Labor leaders accuse officials of playing political games with the budget and ignoring the workforce that keeps the city running.

"Now is the time to invest in our public employees who have not let us down," said Brian McLaughlin of the New York City Central Labor Council. "Years of privatization and productivity schemes from City Hall have gotten us nowhere."

The outcome of these contentious negotiations between city government and labor have an impact not only on the city's fiscal health, but also on how the schools run, how clean the streets are, if crime goes up or down, and how long it takes to put out a fire.

THE CITY'S WORKFORCE AND COSTS

New York City employs about 286,000 full- and part-time workers. The full-time workforce is often divided into three categories:

- 96,000 teachers

- 64,000 uniformed employees - police, firefighters, corrections officers, and sanitation workers

- 80,000 "civilian" employees - all of the workers that do not fit into other categories.

In the last three years, in an effort to streamline government and cut costs, the city's workforce has decreased by 5 percent or 14,000 full-time positions.

But despite cuts, the city's overall labor costs have risen 20 percent.

The reason, say fiscal watchdogs, is that New York's overtime, benefit and pension packages are more expensive than elsewhere in the country and the costs continue to rise.

In 2003, New York City paid out $870 million in overtime, nearly double the total a decade ago. The average cost of a New York City worker is now more than $82,000 a year, including pay and benefits, according to one report (in pdf format).

"A significant part of the city's budget problem is caused by growing personnel costs," said Diana Fortuna of the Citizens Budget Commission. "The city will be continually forced to cut services if these costs are not curtailed."

In addition to the city's active workforce, New York also supports 180,000 people who have already retired.

Pension costs are the fastest rising share of the budget. According to the mayor's office, pension and fringe benefit costs rise 5 percent each year; by the year 2008, the city will pay $10 billion a year in pensions or about 20 percent of the annual budget.

WHAT CITY HALL WANTS

Since he took office in January 2002, Mayor Bloomberg has taken a fairly tough approach toward unions.

The mayor reduced the city's workforce. He threatened to jail MTA workers if they went on strike in December of 2002. And last year, he demanded $600 million in concessions from unions to help balance the budget, when they did not produce what he wanted, he blamed union leaders for tax hikes and service cuts.

"When you do something and help us, then afterward, you can get it back," the mayor told labor leaders.

The mayor's latest budget also proposes a new pension level for city employees that would apply to new employees. It would reduce cost of living adjustments, increase the age and service requirements, and require 10 years of work for city workers to become fully vested in the program. Such a program could produce a total of $10 billion in savings for the city between now and the year 2025, according to City Hall.

The New York City Council, which has no direct role in collective bargaining agreements, but must still approve the budget, generally agrees with the mayor, and has made tax cuts a priority.

"All city employees could use a raise, but unfortunately we are still in some financially difficult times," said Councilmember Joseph Addabbo, Jr., chair of the council's civil service and labor committee.

The City Council also has the power to bring certain labor issues into public view and help shape the negotiations - either by raising workers complaints or uncovering inefficient work rules.

Last fall, Councilmember Eva Moskowitz, who chairs the education committee, held a series of hearings on school employee work rules and helped bring to light how difficult it is to get rid of poorly performing teachers, a process that can sometimes take up to two years.

The union was angered by the council hearings, especially since the overwhelmingly Democratic members usually side with unions in disputes with the mayor. Still shortly after the hearings, the United Federation of Teachers released a plan to overhaul the disciplinary system for teachers, including calling for a task force of pro bono lawyers to clear the backlog of 200 teachers who still receive full pay while awaiting dismissal.

WHAT THE UNIONS WANT

While the mayor can point to rising costs and budget problems, city workers say new contracts and pay raises are long overdue.

Every city union contract - for teachers, police, firefighters, sanitation, corrections, and other workers - has expired. While this is not unusual and new contracts are agreed to retroactively, many workers feel abandoned by the city at a time when taxes, subway fares, and housing costs continue to rise.

Teachers

In June 2002, Mayor Bloomberg negotiated a new contract with teachers that his predecessor Rudolph Giuliani had put off. It included raises of between 16 and 22 percent depending on experience in exchange for working 100 extra minutes a week.

However, since then, relations between City Hall and the United Federation of Teachers have turned contentious.

Recently, the mayor proposed replacing the current 42-year-old, 200-page teachers' contract with an 8-page document that gives the city unprecedented control over educators and the classroom. Bloomberg's teachers contract would:

- Add more days to the school year.

- Bar teachers from doing union work during the school day.

- Eliminate sabbaticals teachers.

- Cut the number of unused sick days that can be cashed in by retirees.

- Give bonuses to teachers to work in low performing schools.

United Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten rejected the proposal and called it a "kick in the teeth."

However, teachers say it is not just about the details of work rules, but giving teachers the respect they deserve. The mayor, they argue, is making it more difficult to recruit and retain quality teachers.

Forty-five percent of all New York City teachers either quit the profession in their first five years or leave for a teaching position outside the city, according to the union. Currently, New York is having an especially difficult time recruiting math and science teachers. The poorest schools have the highest teacher turnover rates, which means those students are put at a further disadvantage.

Uniformed Workers

Contracts with uniformed services - police, firefighters, corrections, and sanitation worker - often follow a pattern; if one union gets a new contract, the others get agreements on a similar scale.

New York police officers, whose contract expired in July 2001, have long been seeking pay that is equal to officers in other places. The starting salary for a New York City police officer is $36,878, compared to $47,853 in Yonkers.

Like teachers, police officers say it is difficult to recruit and retain officers who can make much more in the suburbs. Police officers also stress the danger of their work - risking death while working for the city. In January, the Patrolmen's Benevolent Association unveiled a massive billboard near Times Square that read: "NYC Cops, ranked #1 in the nation in fighting crime - ranked #145 in the nation in salary: It's time to fix the injustice."

Last year, the city tried to broker a deal with correction officers union and its 9,000 members by creating longer shifts, but the deal fell apart when the city wouldn't put the money saved into pay increases. Like the police, correction officers point to the stressful and dangerous nature of their work.

"You want me to turn this entire municipal work force into a slave organization," said Norman Seabrook, president of the Corrections Officers Benevolent Association. "I don't think so."

In many ways the New York City Fire Department is still trying to rebuild the department after they lost 343 firefighters and a combined 4,000 years of experience on September 11, 2001. Last year, the city closed six firehouses in an effort to save money in the budget. Last week, the mayor agreed to increase the number of firefighters from four to five on additional engines. Union officials maintain that increased staffing is critical for ensuring the safety of firefighters and city residents.

"The difference between a five-man engine and a four-man engine is dramatic," said Stephen Cassidy of the union. "It actually takes twice as much time for a four-man engine to get water on a fire."

And the sanitation workers were angered when 217 workers were laid off for budget cuts. Those workers have now all been rehired and workers say they deserve raises and a new contract, which expired in October 2002.

Civilian Workers

City workers represented by District Council 37, which is the city's and the nation's largest union with over 125,000 members, feel particularly abandoned by the city.

The union includes many lower paying jobs like city lifeguards, traffic employees, museum employees, custodians, social workers, and health care workers. The average District Council 37 member makes $29,000 a year, according to a union spokesperson.

"Many are raising families on this salary and having trouble making ends meet," said Lillian Roberts of District Council 37. "With transit hikes and higher taxes, everything has been raised but their salaries. We urgently need a fair contract now."

Union leaders also point out that when the mayor praises city government as being more efficient, it is the everyday workers that are making it happen.

COMPROMISES AND CHALLENGES

There have been some agreements that demonstrate that the mayor and the unions can negotiate when they want to.

In December, both sides reached an agreement on health benefits. City workers and retirees will now pay on average $200 more in out-of-pocket health expenses each year. In return, the city agreed to increase its contribution to a fund for cancer, asthma, and drugs.

Both sides called it a "win-win" agreement: the city saved $100 million and union members preserved their benefit packages. Labor leaders also said that it might be a major step in moving toward new contracts.

But as workers go longer without new contracts and raises, the tension between city government and unions grows.

In New York City, city workers are not legally able to strike, so protests, work slowdowns, and sick outs are options for disgruntled workers. These actions can translate into poorer performing schools, dirty streets, and eventually less money for city services.

It is often an election that gets the city and unions to sit down and negotiate.

Right now, many union leaders are faced with a dilemma: negotiate with the mayor or try to oust him in hopes of getting someone more sympathetic.

In a recent letter to members, Weingarten said that there was a "window of opportunity" to negotiate a new contract before Bloomberg's 2005 reelection campaign, but she said she has grown more pessimistic in recent weeks.

Mayor Bloomberg, who was elected without union support in 2001, has told labor leaders that he plans on being around for a while.

"Anybody that wants to bet that I'm not going to be around in two years and they'll wait it out, that's a pretty stupid bet, if you think about it," the mayor has said. "I'm going to get re-elected."

#####

RELATED ARTICLES

School Contracts: Do They Serve Students? (January 2003)

Police Pay: What Is Fair? (September 2002)

Labor and the New Workplace (June 2002)

Labor's Bill Comes Due(January 2001)

LINKS

City Office of Labor Relations

United Federation of Teachers

District Council 37

New York City Central Labor Council

New York City Police Benevolent Association

Uniformed Firefighters Association

New York Workers Need a Raise

All New Yorkers have had to brave record low temperatures, wind, snow, sleet and rain this winter. But for Joaquim Gonzalez and thousands of other delivery people throughout New York City the past several weeks have been particularly harsh. They have had to battle the cold, slush and ice for between seven and ten hours a day, six or seven days each week. And no matter how much Gonzalez works, he still cannot get ahead.

All New Yorkers have had to brave record low temperatures, wind, snow, sleet and rain this winter. But for Joaquim Gonzalez and thousands of other delivery people throughout New York City the past several weeks have been particularly harsh. They have had to battle the cold, slush and ice for between seven and ten hours a day, six or seven days each week. And no matter how much Gonzalez works, he still cannot get ahead.

He earns the minimum wage for tipped workers: $3.30 an hour. (Workers who do not have the opportunity for tips must be paid at least $5.15.) That means eight hours of biking around snowy, crowded Manhattan streets guarantees him a mere $26.40. Sometimes he lucks out and gets a few good tips. Other times he doesn't. Last month, Gonzalez rode his bicycle more than 70 blocks in the snow for a 50-cent tip. After paying for rent, food, subway, clothes, medicine, and maintenance of his bicycle, Gonzalez is left with almost nothing.

Gonzalez, like other minimum wage workers throughout New York State, is getting a raw deal. Unlike a growing number of states, New York has failed to take action to fix the problem of a stagnant and inadequate federal minimum wage by increasing the state minimum wage.

Since 1968, the purchasing power of the federal minimum wage has fallen by 40 percent. Throughout the 1960s and 70s, a full-time, year-round worker earning minimum wage could keep a family of three above the poverty line. Today, a full-time, year-round worker earning minimum wage can barely get his or her family three quarters of the way out of poverty.

Inflation has eroded the value of the dollar, and the minimum wage has failed to keep up. In the end, the New York State government is not all that different from the woman who tipped Gonzalez 50 cents. It is undervaluing its workers and doing the very least it can get away with.

Nationally, low-wage workers' real wages (taking inflation into account) increased by 5.5 percent between 1989 and 1999, but New York State's low-wage workers saw their real wages fall by 5.5 percent over the same period. Similarly, poverty declined in the United States during the 1990s, but it increased in New York State, as the income gap between rich and poor New Yorkers grew dramatically.

Governor George Pataki's proposed 2004-2005 executive budget does nothing to fix the problems of low-wage workers. In fact, Pataki's proposals would make the situation worse. The governor has proposed reducing food and living allowances for long-term welfare recipients, even though inflation continues to decimate the value of New York State's welfare grant.

Scapegoating the poorest of the poor, though, is nothing new. What is remarkable is that Governor Pataki's budget fails to reward work in any meaningful way. In fact, he has proposed a reduction in the amount of earned income that working welfare recipients can keep before losing benefits, thereby creating a disincentive to work. Additionally, his continued failure to increase New York State's minimum wage to keep up with inflation, and keep it pegged to inflation in the future, punishes hard-working New Yorkers.

New York is full of people who face rough labor conditions and the daily indignity of struggling to survive. Their treatment affects all of us. Poverty wages for workers translates into fewer consumers for business. When under-paid workers get sick, the government -- in other words, the taxpayer -- gets stuck with the bill.

New York's neighbors in Connecticut and Massachusetts have already raised their minimum wages to $6.90 and $6.75 per hour respectively, and neither state has experienced job losses as a result. Moreover, research done in California suggests that a higher minimum wage has important secondary benefits, such as improved health for low-wage workers and a greater likelihood that their children will graduate from high school.

It is high time for New York to join the growing number of states and the District of Columbia that have raised the minimum wage above the federal minimum of $5.15 per hour. Governor Pataki should support legislation currently pending in the State Assembly that would strengthen enforcement of minimum wage violations and raise the minimum wage by almost $2. This legislation would directly benefit more than 500,000 New Yorkers, and indirectly benefit many more, while saving the state money and giving the economy a boost. Joaquim Gonzalez, like all of New York State's minimum wage workers, deserves a raise.

Andrew Friedman is a senior fellow of the Drum Major Institute for Public Policy; Fernando Ferrer, former Bronx borough president and candidate for mayor, is president of the institute.

#####

Related Story:

A Minimum Wage Increase Will Hurt Small Business and the Working Poor

by Mark Alesse and Matthew Guilbault