Mentally Ill Seek More Independence

It's the simple things in life that bring Irene Kaplan a sense of joy -- things most people take for granted. Deciding when she goes to bed, how to decorate her apartment, when to take her medicine. She likes buying her own groceries, choosing what she eats and how she cooks it; lately she has been experimenting with Caribbean spices and wants to bake more bread.

"What people like about it is the smell of bread baking. It's absolutely drool worthy. I've been experimenting with multigrain bread and Italian style. I've been using different healthy oils. It's a whole new, wide open world once you get out of the home," she explained.

A bout of pneumonia and a telegram letting her know that she no longer had a job led to Kaplan's stint as a homeless person and her eventual arrival at an adult home, a for-profit facility where the state places mentally ill adults. Kaplan spent 16 years in such a home.

Earlier this month Federal District Court Judge Nicholas Garaufis ruled that keeping mentally ill people in these homes violated their rights by preventing them from functioning as part of society. The state is still deciding whether to appeal a decision that could have a dramatic impact on how New York cares for people with mental health problems.

Kaplan, though, has already left her home. Thanks to state funding for supported housing for 60 patients, she lives in her own small apartment in Brownsville. She gets therapy and assistance from local groups as she works to reconstruct her life.

Now as a result of Garaufis' ruling, more patients like Kaplan may have a similar chance at freedom. Whether that happens, though, depends on how the state responds.

Not So Welcome Home

Since the state phased out its mental institutions in the 1970s, it has grappled with how to deal with mentally ill adults. For-profit homes, such as the one where Kaplan lived, have become the standard treatment centers for mental patients in New York. Over 4,000 New Yorkers with mental issues are housed in adult homes throughout the city.

In 2002, the New York Times ran a series about adult homes and the problems that ran rampant in them at the time. Reporter Clifford Levy found abuse and neglect of patients and that homes subjected residents to unnecessary medical procedures to take advantage of Medicare. In a 2003 article the Times referred to adult homes as "little more than psychiatric flophouses."

Following the Times series in 2002, advocates and the Pataki administration moved to reform the adult homes. The administration proposed spending $8 million to send social workers and caregivers to adult homes to increase the quality of care and evaluate whether some patients would be better served in other settings. But after strong lobbying by owners of adult homes, the legislature took $6 million of that money and allocated it to a program to give cash bonuses to adult homes that fared well good inspections -- essentially, advocates say, bribing them to provide a decent standard of care.

A taskforce was put together by the Pataki administration to address the care of the mentally ill. It recommended that the state move thousands of mentally ill adult home residents to apartments or small homes in communities. This was all supposed to be accomplished by March of this year. In the end only 60 patients were moved including Kaplan.

Over the past several years, some of the abuses have been addressed with better monitoring from the state. Adult homes are licensed and regulated by the New York State Department of Health. The State Office of Mental Health licenses and regulates mental health providers that diagnose and treat patients in the adult homes. Homes are regularly inspected.

Patients and advocates say there are good homes and bad ones, but as a whole they say adult homes effectively cut off patients from the outside world while fostering a sense of dependency and helplessness. In effect, these new institutions, they say, have become prisons that warehouse patients without any eye to letting them return to society.

Going to Court

In 2003, lawyers representing thousands of adult home patients and advocacy groups filed a suit in U.S. District Court in Brooklyn alleging that the state had violated the Americans with Disabilities Act by segregating the mentally ill.

The lawsuit said that most patients would be better off in their own apartments where they could receive treatment. This, the suit said, would also save the state money. It asked the court to block the state from sending the mentally ill to adult homes.

In his decision, Garaufis ruled in the complainants' favor by agreeing that the state violated the rights of the mentally ill in New York City. But he stopped short of barring the state from sending patients to adult homes. Still, Garaufis indicated in the decision that the state should consider providing apartments or small homes to patients who are not a threat to themselves or others.

Garaufis ordered the state to submit a "remedial plan" by October. The plaintiffs, including disability advocates, will be allowed to critique the plan.

The ruling only applies to homes in New York City, but the state will likely have to overhaul the entire system by which it services the mentally ill. Advocates expect the decision to have national ramifications since many other states also rely on adult homes to care for the mentally ill?.

The Next Move

So far the Paterson administration has remained mum on its plans. Jill Daniels, spokeswoman for the state Office of Mental Health, said that the judge's 210-page decision is still under review. "It's a long decision. Multiple agencies are involved," she said. Paterson's office did not return calls for comment.

A number of advocates are calling on the Paterson administration not to appeal the decision. Glenn Liebman, chief executive officer of the Mental Health Association of New York State, said New York should instead do now what it could have done to avoid the suit in the first place. "The state should have moved years ago to change conditions in adult homes. The state should have done a better job. They did some good things but they did not take a comprehensive approach," he said.

Saying he is "pleased with the decision," Sen. Tom Duane, who serves on the Senate Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Committee, said he thinks "the Paterson administration is very sympathetic" to the ideas expressed in the ruling. Duane said he plans to work with the administration to develop more supported housing for the mentally ill.

Lisa Newcomb, director of the Empire State Association of Assisted Living, which represents some homes, criticized the decision for casting the entire adult home industry in a negative light. She said the decision seems to assume that many of the patients in the homes are capable of functioning at a higher level than they actually can. According to Newcomb, sizable number of patients probably need the care and supervision the homes can provide.

Newcomb added, though, that she recognizes that more options for independent living are needed. "Honestly, we need more of everything," she said.

Paying for the Alternative

The real struggle facing the state is likely to be financial. Advocates acknowledge that the state is confronting fiscal crisis and that finding affordable housing in New York City is no easy task. But they say that providing the mentally ill with an apartment and finding them therapy and other services in their areas will actually be less expensive than paying to support their stay in large adult homes. And advocates say that a support structure of case workers and healthcare workers will be readily available to the patients.

Garaufis agreed. In his decision, he wrote that it costs at least $7,946 a year less per patient for the state to provide "supported housing" to the mentally ill than to pay for a stay in an adult home, which costs around $47,946 a year. Garaufis also found that supporting a patient in an adult home costs Medicaid twice as much as it does to keep a patient in supported housing.

Advocates insist there are a number of funding options, federal and otherwise, that could initiate a supported housing program across the state. They say the program could be ramped up over the next few years.

The other financial consideration comes from the adult home industry, which is not exactly keen on giving up a steady source of income. Advocates say adult homes are represented by a "very powerful lobby," that has been able to get its way with the legislature in the past.

Rediscovering Independence

In his decision Garaufis pointed to the stigma of living in an adult home and said it can curtail social and professional options. The rules and restrictions, such as limits on visitors and not being able to have a phone, run counter to the image of an independent functioning person. Garaufis also noted that, while homes tend to focus on training in life skills, such as cooking and shopping, residents rarely have the chance to apply their skills in society.

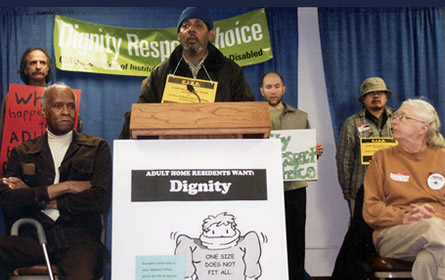

Advocates acknowledge that not all patients will be ready to live on their own, but they say they should have the choice. Kaplan, who as a member of the Coalition of Institutionalized Aged and Disabled has been very active in advocating the rights of the mentally ill, agrees.

She admits that some patients need more help than others, but believes more harm than good is being done by keeping them all in one place and segregating them from society.

At Surf Manor Homes in Coney Island Kaplan was told what and when to eat and when to bathe. She had limited contact with the outside world and recalls being scolded for changing her linens, being coerced and intimidated into following instructions, and having to pick her roommate off the floor at night. She particularly remembers suffering summers without air conditioning.

Kaplan said she knew she was simply "too functional" to be in an adult home. "I did a lot of things for myself: I clean my room, take care of my personal hygiene needs. I didn't need that kind of support," she said.

While Kaplan recognizes that not everyone is as functional or independent as she is, she said living in a home erodes a person's self reliance. She says it is hard for some, after years of regimentation, to fight for more freedom or even to want it. "They do your shopping, do your cooking, help you shower. It is not conducive to a sense of independence," she said

Ready for the Next Move

Derek White, though, wants to move on. Three or four years ago he was living on the streets and addicted to drugs when he found himself in a hospital in White Plains. From there White was sent by health officials to Palisade Gardens, an adult home in Westchester where he received the support he needed to rebuild his life without drugs. White became involved with the Coalition for Institutionalized Aged and Disabled -- he is the president of the chapter in Palisade Gardens -- and works as an inspector for the local Board of Elections.

White credits the home for getting him back into the swing of things. "This place is not bad. ... I know for a fact that a lot of homes are a lot lesser," he explains.

But still White is ready to move on. He is tired of going to dinner only to find ground beef replaced by ground turkey, and ribs and pork chops pulled off the menu because of budget cuts. "I think I'm ready to go now," he said without any sense of anger or frustration. "I miss doing things for myself. I miss cooking, I miss choosing what I get to eat."

White imagines himself in a one-bedroom apartment, perhaps a studio, anything to get him back into society and making his own choices. He still wants some of the counseling and support he gets from the state. For now at least, no appropriate option is available.

"I've got nothing bad to say about this place. They helped me," White said. But now if I could get a little bit of help to get out of here. ... I'm ready to move on."

At this point the hopes of White and hundreds of other patients rest in the hands of the state.

Health Care, Development Dominate Debate in Forest Hills

With its pleasant residential neighborhoods and fairly affluent population, District 29 in Queens avoids many of the ills facing the city's grittier areas. But like so many Americans, residents of this area have major concerns about health care.

The closing of hospitals and the delivery of medical services to the district's residents has been a key issue in the campaign for the City Council seat currently held by Melinda Katz, who decided not to see re-election and is running for city comptroller. Like people in other parts of Queens, residents of the area also are concerned about development.

The race features six Democrats: Heidi Chain, a lawyer with the city Department of Finance who received the 2008 New York Police Department Woman of the Year award; Albert Cohen, an immigrant from Tajikistan, who has his own law practice; Michael Cohen, who represented Forest Hills in the State Assembly from 1999 to 2005; Melquiades Gagarin, media manager for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund; Karen Koslowitz, a former City Council member; and Lynn Schulman, the chair of Community Board 6.

The winner of the Sept. 15 primary will run against the Republican candidate, Bartholomew F. Bruno, in the Nov. 3 election.

A Hospital Shortage?

In a span of 12 months, three hospitals in Queens have closed. One, Parkway Hospital, the city's only privately run hospital, was in District 29. (The other two were Mary Immaculate Hospital and St. Johns Queens). In the wake of the closure, residents of Kew Gardens and surrounding neighborhoods worry about a shortage of hospital beds and long waits at emergency rooms.

The volume of patients at Forest Hills Hospital has increased by 40 percent from a year ago, and the number of patients who are being admitted is up about 12 percent, according to public relations spokesman for Forest Hills Hospital Terry Lynam.

"They [hospitals] have people practically in bunk beds," said Barbara Stuchinski, a local resident.

Chain expressed dismay that the hospitals ever were allowed to close. "They bail out banks, we bail out General Motors, and we didn't bail out the hospitals to protect the folks in Queens," she said, her tone reflecting her disbelief. To help fill the gap, she would establish a service helpline to provide immediate round-the-clock help.

The closing has had very real effects, according to Schulman, who works at Woodhull Medical Center in Brooklyn. "The number of ambulance tours in the districts have gone down so response time has gone up," she said. She hopes to open an ambulatory care center in the district to provide immediate assistance to residents.

In Michael Cohen's view, the closed hospitals must be replaced. "Either reopen those hospitals or open new facilities," he said. "On a temporary basis, we should expand a walk-in clinic, but that is no substitute for a hospital." Money for this could come from a stock transfer tax or a bond issue approved by voters.

Albert Cohen would try to reduce the burden on the hospitals by promoting preventive care. To accomplish this, he would invest in medical screenings to identify health concerns before they send an individual to the emergency room.

Rezoning the District

The recently approved rezoning of Forest Hill's Austin Street won applause from the candidates. Austin Street has become the trendy shopping destination for residents with big name stores such as Sephora and Barnes & Noble. The rezoning is intended to promote more residential development in the already crowded area.

Koslowitz, who has very distinct red hair, has been credited with shutting down strip club Runway 69 when she last served as council member. That helped create the current boom in development on Austin Street.

While Michael Cohen supports the overall rezoning, he has concerns about parking. "I am critical in the plan with the amount of mandatory parking that would be provided," he said.

Albert Cohen has also focused on parking problems in the district, holding a press conference to complain about angled parking spaces on 108th Street and the ticketing of driver who don't back into their spot.

On another development question, five of the candidates have endorsed the rezoning to limit sizes of building in the Cord Meyer area, but in a debate, Albert Cohen opposed the change. He said the new limits are aimed at the Bukharian community, many of whom have built large homes in that neighborhood. According to TimesLedger newspaper, the rezoning " has highlighted the tension between the Bukharians and non-Bukharians."

Gagarin would change zoning rules to allow for the creation of more schools.

As the area has boomed, rents have increased. Many resident worry about the expense and fear they might have to another neighborhood. Schulman, vowed to advocate for legislation that would let the City Council set rent guidelines, as opposed to having the state legislature do it.

In the Home Stretch

The campaign has been largely free of acrimony, as the candidate compete for money and support in advance of primary day.

Chain, who has the support of many police groups, leads in fund-raising, but there's a bit of a twist. Unlike her opponents -- and the vast majority of city candidates apart from Mayor Michael Bloomberg -- she is not participating in the public finance system, reportedly because she does not think candidates should take taxpayer money in these tight economic times. She has raised almost $207,000 in private donations -- with more than $125,000 of that coming from herself.

Now it turns out Chain may not have saved the city any money afterall. City Hall has reportedthat Chain's fundraising and not particpating in public financing "triggered a provision of the Campaign Finance Board program that gives opponents an additional $95,000 in public funds. That equals $7,000 more than she would have received had she joined the program and received matching funds for raising the maximum amount from others."

Among the others, Koslowitz has raised the most private money -- $93,730, followed by Schulman with $87,260, Michael Cohen with almost $46,000 and Albert Cohen with about $43,000. Gagarin trails with $17,599.

Schulman, who ran unsuccessfully for the seat eight years ago, has the backing of the Working Families Party and the Service Employees Union this time around. The

Times has endorsed her as well.

Koslowitz, who has the Independence Party nomination, is backed by City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, who has campaigned with her.

Chain has support from several police groups

This article was written under a partnership between Gotham Gazette and the Baruch College's Department of Journalism and Writing Professions.

Closed Hospital Plays Key Role in Jackson Heights Race

Any number of potential City Council candidates saw their plans thrown into turmoil in late 2008 when the City Council voted to extend term limits and allow incumbents, including Mayor Michael Bloomberg, to run for a third term in their respective New York City offices.

The move whittled away a number of challengers in District 25, which encompasses Jackson Heights, Corona and East Elmhurst. But two -- Daniel Dromm and Stanley Kalathara -- have remained in the primary race to challenge incumbent Helen Sears. With a spirited primary race underway, the conventional wisdom -- that an incumbent always wins -- might not hold true here. The winner of the Democratic primary will face Republican Mujib Rahman in November.

The diverse district faces an array of problems, including a lack of health facilities, development and overcrowded schools. While the candidates all seek to address those issues, their platforms emphasize different areas. Sears, who was first elected in 2001, is taking on the district's health care dilemmas; Dromm, a schoolteacher and union leader who is also a gay activist, is focusing on education reform; Kalathara, a lawyer and businessman, wants to clean up the neighborhood by improving the quality of life and attract dollars that would otherwise be spent in Manhattan.

The Hospital Closing

The fault line of this campaign is the recent closing of St. John's Hospital. When Caritas Healthcare, the company that ran St. John's Hospital and Mary Immaculate Hospital, also in Queens, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy early in 2009, the hospitals were unable to keep their doors open. Even before Caritas' bankruptcy, St. Johns had been plagued by a shortage of beds and outdated equipment.

Consequently, the 100,000 patients serviced in their emergency rooms must now go to other medical centers. Residents of Corona, East Elmhurst and Jackson Heights have to use the already strained resources of the two remaining neighborhood hospitals, Holliswood and Queens Hospital Center.

Sears' opponents hold her responsible for the closure of St. John's. Sears maintains that she moved quickly to keep the health center open. New York State extended money to the hospital, but said it could not make regular contributions.

"She only showed up at a protest at the very end. She should have started [taking measures to avoid this] since her election," said Dromm.

Kalathara said, "I am not going to play the blame game." But he cited his concern about the impact of any re-emergence of swine flu this fall, noting that the two remaining hospitals serving the densely packed district were already seeing a doubling in cases

Planning for the Future

Sears, a former healthcare professional, has spent a great deal of time defending her past two terms in local debates, rather than speaking of her aspirations for a third term. During her two terms, she said, the Corner Care Pavillion opened as a health center for neighborhood residents. Now she said, it will add a woman's health clinic. "This district is incredibly diverse -- every country in the world is represented here," she said. "A woman's clinic will bridge cultural differences and will provide and teach women how to seek healthcare."

Interviewed in a restaurant where the waitress speaks Spanish, Dromm cites his experience in advocacy and community affairs. "I recently organized a documentary screening about Muslim Sikhs to be shown in a Jewish center," he said.

His self-titled Dromm Plan vies to improve life for community residents with measures such as ending the self-certification practiced by real estate contractors and reducing noise pollution by pushing through legislation. He also proposes measures to help the area's many immigrants, such as addressing the employment scams which they too often face. "A center for day-laborers where they could meet potential employers would create safer situations and ensure union jobs by bringing immigrants into them," he said.

Kalathara, a self-made man who prides himself on his awareness of neighborhood difficulties, holds his interview in his neighborhood law office where the clientele are of Indian and Latino origin. He said he wants to address foreclosures, job loss and safety on Roosevelt Avenue and Junction Boulevard. "Installing lights, on stretches of blocks that often go without them is another plan to ease crime," he said.

He plans to push legislation to secure daily garbage pickup for his district and proposes the widespread use of charter schools to improve the education standards in city schools. "I will donate 10 percent of my salary to give funds to the most worthy community organization or school in this district," he said.

Kalathara extols his campaign as "a message of belief, opportunity." Holding himself up as an example of the American dream -- Kalathara worked his way up from an Indian immigrant-busboy to a lawyer -- he said, "I want to set an example for others." Indignant about the economic disparities between his district and many Manhattan neighborhoods, he said, "Queens is not a second class world. I want to make sure Queens citizens are treated first class,"

On the day of his interview, Kalathara was fighting to stay on the ballot. He sat, confident behind his desk in his Queens law office. "I've sent one of my lawyers to handle the case," he said. When questioned about the validity of the signatures on his ballot petitions, he said simply that Dromm, who had challenged them, "is a sour grape."

Votes for Immigrants

In this district of many immigrants, there is debate about Resolution 245, which would give non-citizens the right to vote in New York City elections. Dromm strongly supports the act, while Kalathara merely agreed. At a recent debate, Sears had no opinion to give, saying, "I'm here to tell you that I'm not sure where I'm on this. I haven't given it much consideration."

The passage of resolution 245 would have an enormous impact on the political landscape of New York City, particularly in this heavily immigrant Queens District. Estimates place those who are of age but cannot vote in New York City elections at 1.3 million, easily more than one-eighth of the city's overall population.

Explaining his support for the resolution, Dromm said, "There should be no taxation without representation. This is a basic American tenant, and it's the key to ones destiny."

The Anonymous Charges

On a far murkier level, controversy also has arisen over anonymous leaflets about Dromm that some have characterized as part of a "homophobic smear campaign." The leaflets reportedly allege that, as a 16-year-old, Dromm was arrested for prostitution. He has said he was simply kissing his boyfriend but that, in the 1970s, " being gay meant that you could be put away against your will in a mental institution."

Kalathra and Sears both condemned the attacks, although Sears has been criticized for not speaking out sooner and more forcefully against the advertisement.

Money and Support

Sears remains the campaign heavyweight in terms of budget. She leads with $128,493. Dromm is second in funds with $103,958 and Kalathara with $92,489.

Dromm has endorsements from the Working Families Party; Service Employees Union Local 1199, which represents healthcare workers; the United Federation of Teachers, as well as by local politicians including state Sen. Tom Duane and three City Council members from Queens.