Bus Bunching

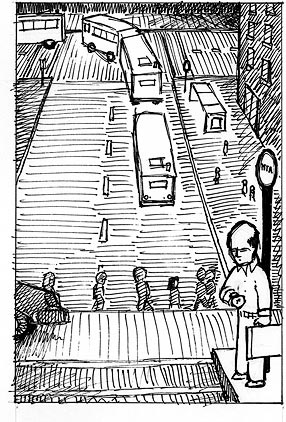

You are waiting for the M104 bus at Broadway and 116th Street. Minutes go by, and it does not arrive. Then, maybe 20, 30 minutes later, three M104s arrive, all in a clump.

You are waiting for the M104 bus at Broadway and 116th Street. Minutes go by, and it does not arrive. Then, maybe 20, 30 minutes later, three M104s arrive, all in a clump.

Sound familiar? This problem, called bus bunching, has been deemed a "scourge" by the Straphangers Campaign, a transit riders advocacy group.

In 1999, M104 buses arrived bunched together 60 percent of the time, the Straphangers found. And it was not the only bus route where buses arrived all at once — or not at all.

"The Transit Authority should offer free straitjackets to anyone waiting for a crosstown bus," Lenore Skenazy once wrote in the Daily News, describing her trials with bus bunching.

So many Brooklyn commuters complained to State Senator John Sampson of Canarsie last year about the B-42 bus bunching on Rockaway Parkway, that he wrote a letter of complaint to New York City Transit Authority president Lawrence Reuter.

Reuter wrote back, saying that the B-42 line was prone to bunching because its buses are scheduled to run just three-and-a-half minutes apart, and traffic problems can easily cause one bus to catch up with the other. Reuter told Sampson that he would tell bus dispatchers to pay more attention to the B-42 to keep them running at regular intervals.

Since then, the B-42's performance has improved, said Beverly Whitmire in Simpson's office.

But bus bunching continues to plague other part of the city. There are several theories about why.

Some think that bus dispatchers are not doing their job, and ensuring adequate space between bus departures. Others say bus drivers probably gather to chat with each other and then all end the coffee klatch at the same time, causing their buses to arrive in a clump.

Gene Russianoff, the Straphanger's Campaign senior attorney, has said that New York City buses are prone to bunching because there are not enough buses on the street to begin with, and bus stops are too crowded. Like Reuter in his response to Sampson, most New York City Transit Authority officials blame traffic congestion.

The problem is so complex that math teachers around the world have posed intricate story problems that involve bus bunching to their students, and a British web site has created a simulation game that shows why so many bus lines fall into the bus bunch trap. It demonstrates that when a bus is late, it will have more people waiting for it at the next stop. This means that it will take longer than usual for everyone to board, delaying the bus even further. Meanwhile, the bus behind it will have fewer people waiting to get on, and so will easily catch up to bus number one.

During the Giuliani administration, the city hired a company to create a satellite tracking system for New York City buses to ease the bus bunching problem In September 2000, after more than two years of delays and ballooning costs, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority fired the company. In test runs, Manhattan's tall buildings blocked the satellites' connection with buses.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority did not give up on the concept though, and neither did Mayor Michael Bloomberg who, during his 2001 mayoral campaign, promised to solve the bus bunching problem. His plan, makes use of Global Positioning Satellite technology to tell dispatchers how far along the route buses are at all times. This would enable dispatchers to regulate the distance between buses and help drivers respond faster to disruptions in service.

Don't get too excited about this though. Initial parts of the project are slated to be done in 2004, but the system is not scheduled to be in place until 2009.

In the meantime, people with complaints or recommendations about buses can call or write Millard Seay, senior vice president of the Department of Buses at MTA New York City Transit, 370 Jay Street, Brooklyn, NY 11201; phone: (718) 243-4186; fax: (718) 243-4400.

Another person to contact is Christopher R. Lake, director, Bus Customer Relations at 25 Jamaica Avenue, Room 1, Brooklyn, NY 11207; phone: (718) 927-7499; fax: (718) 927-7498.

The Straphangers Campaign recommends sending a copy of any complaint to New York City Transit President Reuter at MTA New York City Transit, 370 Jay Street, Brooklyn, NY 11201; phone: (718) 330-4321; fax: (718) 596-2146.

Frustrated commuters can also call New York City Transit's Bus Customer Relations Center at 1-888-NYCT-BUS, or, like the B-42 commuters, call or write to their local politicians.

(Do the buses bunch in your neighborhood or is there another problem with mass transit? Tell us about it by going to the Community Gazette for your area.)

-- Erica Pearson

|

Getting a Stop Sign

Eleven-year old Christopher Adam Scott rode his bicycle across the pedestrian overpass of the Clearview Expressway in Bayside. As he reached the corner of 46th Avenue and the expressway service road, a car struck him, killing him almost instantly.

Eleven-year old Christopher Adam Scott rode his bicycle across the pedestrian overpass of the Clearview Expressway in Bayside. As he reached the corner of 46th Avenue and the expressway service road, a car struck him, killing him almost instantly.

Six years before, 12-year-old John Shim was riding a bicycle in the same spot. He too was struck by a car and died of his injuries nine months later.

Local residents believe a stop sign could have helped save the lives of both boys.

About 200 pedestrians are killed by cars in New York City every year. Traffic engineers suggest that stop signs can help remedy the problem by regulating the flow of traffic in a busy neighborhood. The New York City Department of Transportation says that stop signs should be used to alert drivers and pedestrians as to who has the right of way.

But stop signs cannot solve all traffic safety problems, transportation experts say. For example, the U.S. Department of Transportation, which sets standards for stop signs and traffic lights, cautions, "Stop signs should never be installed as a routine, cure-all approach to curtail speeding, prevent collisions at intersections, or discourage traffic from entering a neighborhood."

And when they are misplaced, stop signs can make a situation worse. "Studies have found when stop sign are placed at intersections where they are not really needed, motorists become careless about stopping," says an information sheet issued by the Center for Transportation research and Education in Ames, Iowa.

Given all this, there is no guarantee that a request for a new stop sign will be granted. The Department of Transportation suggests that residents who believe their intersection meets the requirements write a letter to Transportation Commissioner Iris Weinshall at the Department of Transportation, 40 Worth Street, New York, NY 10013. The department provides an online form for this purpose.

The department refers the request to the Traffic Engineering Unit in your borough. That office makes a preliminary study of the street corner in question, including traffic and pedestrian volumes, vehicular speeds, accident history and sign spacing. Eventually the unit will conduct a field investigation to observe traffic on the street corner at various times and on different days of the week, over a period of several weeks.

The inspectors want to determine whether conditions at the intersection meet federal standards for traffic lights and signals set out in the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices published by the U.S. Department of Transportation.

The investigation takes about six weeks. Then, if the department approves the request, an installation will be scheduled. The sign is usually put in within three or four months.

This sounds efficient and thorough, but is it really?

Not exactly, says Roe Daraio, longtime activist and president of COMET: Communities of Maspeth and Elmhurst Together.

Daraio estimates that 95 percent of her requests for stop signs have been fulfilled. "You just have to be a little creative," she says.

Simply following transportation department's instructions is not enough.

COMET keeps a close watch on corners and records problems, listening to accident reports on a police scanner. "You should always be able to say what dates and times the accidents occur," says Daraio. "The more clearly you express (the problem) to the agency, the more likely they are to respond."

Typically, she writes to the head of the Queens Borough transportation office, Joseph Cannisi, rather than to Commissioner Weinshall, as the city guidelines suggest. Since Weinshall's office receives thousands of requests each year and forwards them to the boroughs, Daraio says, writing directly to the borough office eliminates one step.

Daraio also advises that the letter provide as many details as possible about the street corner, such as how many children live nearby or if there is a school. She strongly suggests enlisting local community organizations in the quest, because they probably have a working relationship with key officials, as COMET does with Commissioner Cannisi.

The borough transportation office works closely with the local police precinct to assess the need for the sign. To get the police on your side, Daraio advises reminding the police of the frequency of accidents on your specific corner.

Sometimes, DOT decides to install a stop sign — even if community residents would prefer another remedy such as a traffic light. That is fine with Daraio.

"I find that when drivers see yellow lights ahead of them, they floor it,' she said. "We know night drivers don't come to a full stop at a stop sign, but at least they slow down a little."

In deciding between a stop sign and a traffic light, transportation officials consider the number of vehicles that go through an intersection as well as how fast they are traveling. Visibility and the presence of other traffic lights nearby can also affect the decision.

But evidence of need does not guarantee that the city will install a sign — or a signal. The intersection in Bayside where the fatal accident occurred still has no stop sign and does not seem likely to get one. Transportation Commissioner Weinshall told the Western Queens Gazette that, while "it's very tragic what happened with this little boy... federal standards were not met" for the installation of a stop sign or a traffic signal

No one has told community residents what precise conditions the intersection fails to meet.

Since the denial of the stop sign, the city transportation department has taken several steps to try to make the intersection safer. It has, for example, installed cone shaped objects to guide oncoming traffic away from the pedestrian bridge and posted a sign on the bridge advising bikers to get off their bikes and walk across the overpass.

Community residents would prefer a stop sign. And at least some of them think they know why their request was rejected. "This is how politics works — red tape," local Democratic Party activist John Bisbano told the Western Queens Gazette. "All they know is numbers."

(Do you need a stop sign in your neighborhood? Tell us about it by going to the Community Gazette for your area.)

-- Nicole Zaray

|

Speed Bumps and Humps

For years, Moseley Avenue in the Annandale section of Staten Island was a dead-end street, probably not very attractive to speeding motorists. But last year, the street was connected to Richmond Avenue. Shortly thereafter, while most of Moseley remained two-way, one block was turned into a one-way street.

For years, Moseley Avenue in the Annandale section of Staten Island was a dead-end street, probably not very attractive to speeding motorists. But last year, the street was connected to Richmond Avenue. Shortly thereafter, while most of Moseley remained two-way, one block was turned into a one-way street.

And that, residents told the Staten Island Advance, started the problem. Drivers do not see the sign alerting them of the one-way street, enter the wrong way and then speed through in an effort to get out. The issue came to a head when a driver going the wrong way on the street hit four parked cars.

To solve the problems residents want better police patrols — and speed humps, little hills in the road designed to slow traffic. The neighborhood has appealed for the humps — known in transportation circles as a traffic calming device — but a spokesperson at Community Board Three in Staten Island said the application is still pending.

According to the city Department of Transportation, speed bumps, about 12 inches wide and three to six inches high, force traffic to slow to about 15 miles per hour. Because they can damage cars and cause motorcycles and bicycles to lose control, they have been replaced on city streets by speed humps, which are as wide as the street, slightly longer than an average car and slow traffic to about 25 miles per hour.

Transportation Alternatives says that calming devices, such as humps, provide the best means of slowing traffic. Unlike traffic signals which are designed to control traffic flow, bumps and humps were developed to slow cars. And they do not need a police presence to make them work.

But traffic calming has created groups of opponents who are anything but calm about the prospect of bumps or humps being put on their streets. "In a democracy you punish the guilty," one such opponent told a reporter. "Speed bumps punish everyone."

When a city tries to install a speed hump, "you generate complaints from neighbors who want to speed," Transportation Alternative Executive Director John Kaehny says.

To try to get a speed hump installed, the transportation department advises writing to the commissioner of transportation at 40 Worth Street, New York, NY 10013. It suggests applicants provide evidence of community support, such as petitions, a resolution passed by the community board, or a letter from a local elected official.

The department says speed humps should go only on local or residential streets — and definitely not on bus routes, truck routes, snow emergency routes or other major thoroughfares.

But Kaehny says that, despite such advice on the department web site, it does not have specific guidelines for speed humps, nor are there federal guidelines that it can rely upon. Without that, he says, city officials do not have the ammunition to fight speed hump opponents and so have been reluctant to install them other than around schools.

About 95 percent of residents may support a speed hump, he says, but "the very vocal minority can carry the day when it comes to stopping things in New York City."

(Do you have problems with speeding drivers in your neighborhood? Tell us about it by going to the Community Gazette for your area.)

-- Gail Robinson

|