Campaign Finance Reform: What's Needed Besides Public Financing?

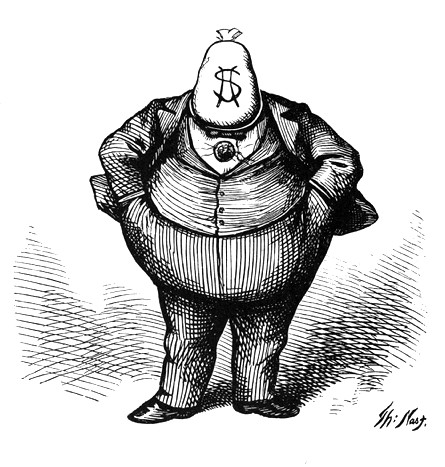

Cartoonist Thomas Nast's classic portrayal of the "fat cat" politician.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s pledge of campaign finance reform has widespread support from New Yorkers fed up with a system in which wealthy individuals, businesses and unions overwhelmingly underwrite the cost of running for state office, thereby endearing themselves to lawmakers.

Much of the discussion over campaign finance reform has revolved around the issue of public financing. A public financing system similar to the one in New York City would encourage average New Yorkers to play a role in funding campaigns, since their donations would be magnified through a public match.

It is important to note that public financing is only one part of New York City’s exemplary system. While their laws and regulations are better than the state’s in a variety of ways, two of them — lower limits and a functioning administrative body — are essential parts of any bill hoping to replicate the City’s success.

Most of the state legislative proposals would significantly lower contribution limits for participating candidates by bringing them close to the more reasonable federal levels.

These lower limits, however, need to apply whether or not candidates choose to participate in a public financing system. If statewide candidates can continue to receive donations of up to $60,800 per donor, will there be any incentive to opt in to the public finance system?

Even these astronomical limits can be easily avoided. Limited Liability Companies are bizarrely exempted from the regular corporate donation cap and treated as individuals. Further, businesses with separately incorporated divisions may give the maximum amount through each division.

Developer Leonard Litwin exploited both of these loopholes to give nearly a million dollars in the past six months, and so far this election cycle has given the governor more than four times the limit usually placed on individuals.

Political parties can receive $102,300 per year from each donor.

However, the five largest parties in the state all have “housekeeping committee” accounts that can receive unlimited donations, even from those who maxed out on this six-figure limit.

While use of this money is ostensibly limited to non-electoral purposes, it goes toward expenditures that few logical individuals would believe exist outside the realm of campaigning, such as the hiring of campaign staffers, paying rent on campaign offices, and running push-polls on behalf of candidates campaigning for office.

New York’s Republican Party has recently proved how fungible this money can be by doing the functional equivalent of laundering housekeeping funds through two different committees and transmuting it into hard money.

Lowering limits on party fundraising is just as important as doing so for candidates: even those candidates who participate in a public financing system could solicit huge checks on behalf of parties with the tacit understanding that this money would eventually be transferred their way or spent on their race.

It’s also clear that administration and enforcement of the campaign finance laws need to taken out of the hands of the Board of Elections, an agency designed to be partisan. The state Board is incapable of taking any action that goes against the will of members in good standing of either of the major parties.

An example is that each year hundreds of donors give more money than they are allowed by our incredibly lax contribution limits.

Yet the state Board never investigates these most basic violations of the current law — even when NYPIRG has, on several occasions, attempted to help them by providing lists of donors who have crossed the legal threshold. The Board has never taken action against any of these individuals or businesses, many of whom are annual violators.

The state Board is also an anemic administrator. Some recent evidence can be found in the Board’s bungling of a statutory requirement to create rules for the disclosure of independent expenditures, such as those made by Super PACs, by January 1st of this year. Its draft proposal was nearly two months late and failed to capture the spending this law sought to expose. As of the beginning of August it was still not finalized.

With the Board’s history of failure in administering our current weak laws, there’s simply no reason to believe they would be capable of overseeing a new, $50 million per year public financing system.

There are other reforms that NYPIRG and other watchdog groups believe should be part of a campaign finance package, including requiring better disclosure, such as the names of donors’ employers and the identification of “bundlers,” and a lowering of limits for candidates in some of the larger localities in the state.

There will also be several areas in a potential bill that could create loopholes, including letting incumbents carry over their huge war chests into future elections.

These details can be worked out when serious talks about passing a bill commence.

A vigorous public financing system could help New York become an exemplar of participatory democracy.

However, New Yorkers shouldn’t be asked to pay for a public campaign finance system that doesn’t really promise to dramatically reduce the influence of special interests in political campaigns.

We have to get it right, since whatever program is created is likely the one we’ll live with for the foreseeable future: legislators won’t rush to work out the glitches in a system that helps perpetuate their 98% reelection rate.

New Yorkers should echo the governor’s call for overhauling the state’s shameful campaign finance system by exerting pressure on legislators to pass truly comprehensive campaign finance reform.

They should be mindful, however, that any proposals include the reforms needed to make a public financing system successful.

_____

Bill Mahoney is the legislative operations and research coordinator for New York Public Interest Research Group

How the State's Elected Elite Stays in Power

Longtime state Sen. Velmanette Montgomery seen at the first interactive ethics reform forum in Albany on May 4, 2011.

NEW YORK — In an alternate reality, New York is gearing up for the most competitive elections it has seen in years.

District lines have been redrawn to represent voters across the state. Campaign financing has been overhauled to reduce the amount corporations and individuals can give to candidates, while loopholes that allow businesses to skirt limits have been plugged. Good government groups have nothing to do.

But that is not the reality we live in.

Instead, in the real New York, fair redistricting has been put off for another decade, leaving the same old incumbents clinging to their power in the state Legislature. Campaign finance is being largely ignored, though good government groups are spending time this summer trying to rally support to change how elections are financed.

This is, after all, a state with one of the highest incumbent reelection rates in the country.

Not that voters are happy with the representation they get from their state lawmakers. An October 2011 Quinnipiac poll found that 63 percent of New York voters disapprove of the way the members of the state Legislature are handling their responsibilities.

So what is it that keeps state legislators in power? We take stock of the top reasons to get you prepared for this year's election.

Complacency and Familiarity

The simplest explanation for New York’s high incumbency rates, according to Barbara Barr of the League of Women Voters of New York, is complacency and familiarity.

“People will vote for the people they know,” Barr said. “It's very hard for people to break in.”

And once they are in office, elected officials have taxpayer-paid tools at their disposal to keep their name in the public.

For instance, office holders have tools at their disposal that allow them to use taxpayer money to communicate with constituents: They can send out informational newsletters with their names on them until shortly before an election and hold community events.

“There are so many different ways in which incumbents manage to get their names out to the public,” said Susan Lerner, executive director of the advocacy group Common Cause New York. “Incumbents are able to use the power of their office.”

Because of these reasons, this year’s incumbents will be reelected, Barr predicted, “unless they don't want to be or unless something really strange happens.”

The legislators themselves are well aware of these advantages.

“The fact that you can send newsletters, yeah I guess that could be a perk,” said Jim Vogel, spokesman for state Sen. Velmanette Montgomery, who has been in office representing parts of Brooklyn since 1984.

However, Vogel explained that Montgomery uses the newsletter as a necessary means of communication with her electorate, not as a campaign tool.

“She really lets people know what she’s doing,” he said. “The senator has always done a really good job of being there for her people.”

It's Hard to Run For Office

Another impediment to real competition in legislative races is the complex system of petitioning to get on the ballot, according to Lerner.

“If you are a challenger, the petitioning process is very, very onerous," she said.

Often, primary challengers don’t even get a shot at office, with candidates being picked solely by their party officials during a special election.

The parties also run candidates when you aren’t looking.

According to the Citizens Union report of the 212 legislators who took office last January, 26 percent were first elected in a special election, for which the average voter turnout was 12 percent from April 2007 to the report’s writing.

These representatives — whose initial election is barely influenced by the people they represent — are then reelected, with all the advantages of other incumbents.

“That is done to ensure that their replacement is… picked by the structure of the political party, not by the voters,” Lerner said.

Remember Redistricting? Who can forget?

Another way to ensure incumbents’ victory is through the redistricting process.

This year, new districts have been proposed, voted on and signed by Cuomo, but official maps have yet to be released.

CUNY’s Center for Urban Research has a useful guide to the legislature-approved lines, and the state Board of Elections points voters to the legislative task force’s website for maps.

When asked if the redistricting process was going well, BOE spokesman John Conklin said: “I'm not sure if I can characterize it as such.”

Part of the problem with redistricting is that although it is intended to adapt districts to new census data, the process is often used to custom-tailor districts for incumbents.

“Incumbents from the majority parties tend to have their districts drawn to have voters who are more favorable to them in the district,” said Bill Mahoney, research coordinator at the New York Public Interest Research Group.

Because new district lines are drawn by a panel of legislators, a majority of whom come from the party in power, the changes often contribute to the cycle of incumbency.

“If we had an independent and non-partisan redistricting process here, we would have more races that are competitive,” Lerner said.

Partisan redistricting can lead to what Mahoney called “some of the wackiest districts.” One example, cited by Lerner, is Marty Golden’s senate district in Brooklyn, which she described as having a “really, truly bizarre shape.”

She said it appeared to have been drawn "to find as many Republicans to elect a Republican incumbent."

Golden could not be reached for comment.

Is Incumbency Bad?

While good government groups criticize the high rate of incumbency in New York, others say being re-elected repeatedly can give politicians the skills and influence to meet their constituents' demands.

“Being an incumbent just means that [voters] know… that their concerns are going to be addressed by this woman,” said Montgomery's spokeswoman.

And while he acknowledged some incumbents abuse their position, Vogel said that was not the case across the board.

“We all know there have been folks who somehow have been around forever and they don't even communicate with their constituency,” Vogel said.

This year, Montgomery is running in district 25 as opposed to 18 as in previous years due to redistricting. However, the size and shape of her districts are virtually indistinguishable. Her re-election is, in fact, inevitable, says Vogel, because no one is running against her.

“It's kind of a moot point,” he said.