The 2005 City Budget

|

|

Most New Yorkers would probably agree with Mayor Michael Bloomberg when he said that there was "good news" in the city's new $47 billion budget, passed last week and going into effect on July 1st.

The city's economy has improved and for the first time in two years, there were no massive layoffs of police or sanitation workers, no threats to close firehouses or zoos, and no new tax increases. The mayor and the City Council even set aside additional money to build day-care centers, to help the unemployed find jobs, and to build 76 new schools over the next five years.

But the good news did not extend to everyone.

Some critical programs — like summer jobs for young people — were still cut. Teachers, police officers, firefighters and other city workers still have no contracts. And as more details of the budget have emerged, many New Yorkers learned that they may have to give back a portion of their promised $400 tax rebate.

The worst news about the budget does not come from City Hall, but from the State Capitol.

The governor and State Legislature in Albany, which has been called the most dysfunctional legislative body in the nation, have burdened New York City with additional problems. For the 20th year in a row, the state failed to meet its budget deadline. Lawmakers left for summer vacation without complying with a court order requiring them to give more aid to city schools or approving a portion of the city budget that gives tax breaks to residents — and have no plans do so until August.

As a result, the city's budget, which depends on $8 billion in state money, is still in limbo.

WHAT'S IN THE CITY BUDGET

This year an improving economy and higher than expected tax revenues produced a $1.9 billion surplus in the city's budget. The major battle between the mayor and the City Council was over how to spend it.

The new $47 billion budget is divided into the usual manner, with nearly 80 percent of the money going to education, social programs like health and homeless services, and police, fire, sanitation, and corrections (in that order.)

In addition to the regular expenses, this budget also includes $291 million in spending that was not in the plan the mayor outlined earlier in the year, including:

- $38 million to hire elementary school teachers

- $29 million for youth and after school programs

- $22 million to extend library hours

- $19 million for 3,900 day care slots

- $11 million for Legal Aid which offers legal representation to people who can not afford a lawyer

- $10 million to train unemployed New Yorkers for new jobs

- And $7 million for City University of New York scholarships.

"I think the whole city will fare better under this budget," said Washington Heights Councilmember Robert Jackson.

Individual City Council members also lobbied hard for their personal budget requests.

Each council member is given $240,000 to allocate in the neighborhood as they wish. In addition, grants for local initiatives, neighborhood organizations, and cultural events, often called "member items," are part of the mix.

For example, Friends of the High Line, a group working to build a park on an abandoned railway in Chelsea that Speaker Gifford Miller supports, received one of the largest grants of $200,000. A group called Black Veterans for Social Justice received $50,000. And the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum, a cultural institution of Italian-American heritage in Staten Island, was able to secure $15,000. Even the Huskers, a lacrosse team from Far Rockaway got a piece of the pie, with $3,857 for equipement.

WHAT'S NOT IN THE BUDGET

Even with a surplus, some budget items still went on the chopping block.

Summer youth employment, for example, was a major point of disagreement between the mayor and the City Council in this year's budget. More than 5,500 jobs for young people were eliminated.

Council members also complained the District Attorneys were not being given adequate funding. The result, they argued, is that prosecutors are often forced to plea bargain cases and to make decisions based on money.

And while tax breaks were given to New Yorkers wealthy enough to own their own home and families who make less than $20,000 a year, there are no tax cuts for those in the middle of the economic ladder.

"I am disappointed we couldn't get tax benefits for renters or the working people who also need it," said Brooklyn Councilmember Tish James.

Police officers, firefighters, and teachers were also left out.

Most city workers have been without a contract or a pay raise for several years, and although the budget contains about $657 million to pay for salary increases, union representatives say that is not enough to pay workers what they deserve.

"If Bloomberg wants a safe city, a well-educated city, a great city, then he has to offer us a fair contract," said Randi Weingarten, head of the teachers union. "We have all waited long enough."

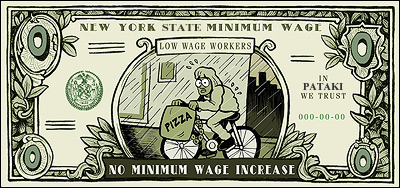

GIVING TAX BREAKS

Tax cuts sparked the major debate in this year's city budget.

Both Mayor Bloomberg and Council Speaker Miller who raised property taxes 18.5 percent two years ago produced rival plans to give some of that money back. Mayor Bloomberg proposed giving $400 to each owner of a co-op, condo, or private house. Speaker Miller wanted to reduce the property tax rate for all homeowners and businesses by two percent.

In the end, Mayor Bloomberg's plan won out and Miller agreed to the rebate that he previously described as a "Bush-style gimmick."

"Budgets are the process of compromise," Miller said later. "I think this is the budget in the best interest of the city. Obviously, it wasn't my first choice."

But as more details of the tax rebate began to emerge, some homeowners learned that they might have to pay taxes on their refund.

That is because the $400 rebate is not an actual reduction in the tax rate, but a check from the city that some New Yorkers may have to report as taxable income. A homeowner who claims property taxes as a deduction and is in a 25 percent income tax bracket, for example, could have to pay as much as $100 in federal income taxes on the $400 rebate.

For his part of the negotiations, Speaker Miller was able to secure a city version of the Earned Income Tax Credit that will give 700,000 low-income New Yorkers up to $215 in tax relief.

Together the two tax relief plans will cost the city $300 million.

But both of these plans have been delayed because the city needs state approval to raise and lower taxes and state legislators in Albany refused to approve the measures. Governor George Pataki, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, and State Senate Leader Joseph Bruno all said they supported the idea in general, but the three men could not work out the details to pass it by the deadline.

"It is an aberration of the law that we need to go to Albany to adjust our own taxes," said Mayor Bloomberg.

If the state passes the measure in August, New Yorkers could get their rebate by October. If not, they may have to wait even longer.

ALBANY INACTION

New York City is required by law to pass a balanced budget each year by July 1, but there is no such law requiring the governor and the State Legislature to do the same.

This year, the usual gridlock in Albany was even worse than usual. State lawmakers missed their April 1 deadline to pass a $100 billion state budget and have no plans to meet again until August.

Albany's inaction has put New York City's budget on hold.

A plan to transfer private bus lines to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which will cost the city about $159 million, is delayed.

In addition to the city's operating budget, which covers the day-to-day expenses of running the city, the mayor and City Council approved a separate $13 billion, 5-year capital budget plan to build and improve schools across the city. The city has asked the State Legislature to pay for half of it, but no agreement has been reached.

And even though the state's highest court has ruled that the state system of funding schools is unfair and gave legislators until July 30 to provide more aid to New York City schools, lawmakers have not agreed on a plan to do so. This means that the city is missing out on $2.5 billion a year in school aid, according to estimates from the Independent Budget Office, and many of Mayor Bloomberg's education reforms are dependent on this additional money. Until the funding comes through, city officials are trying to make do.

"Obviously until we get [this] money from Albany it's not as if we have lots of resources to move," said Schools Chancellor Joel Klein.

For the time being, the governor has passed an emergency spending measure that keeps funding for programs at their current levels, but no one knows when the state will get around to passing a real plan that accounts for about 17 percent of the city budget.

"In the immediate short-term it is not a problem," said Doug Turetsky of the Independent Budget Office, "But if it drags on for months and months, state aid becomes a more serious question."

UNCERTAIN FINANCIAL FUTURE

But even if Albany does come through, the city still faces serious challenges in the next two years.

Earlier this year, the New York State Financial Control Board reviewed Mayor Bloomberg's proposed budget and found that the "city's finances remain structurally unbalanced."

Medicaid payments, employee pensions, and union contracts are expected to increase dramatically in the future. The city is also relying heavily on temporary increases to the personal income and sales taxes that will expire over the next two years. Fiscal watchdogs warned the mayor and the council that their tax breaks and increases in spending could create problems in the future.

This year's surplus of $1.9 billion is expected to turn into a $3.7 billion deficit by next summer.

That means that cuts to social programs, layoffs, and tax increases: The "doomsday" budgets of the past two years may return.

Where's Our $21 Billion?

Several months after September 11, 2001, President George W. Bush detailed $21.4 billion in pledged federal aid to New York City to help rebuild after the attacks on the World Trade Center.

Three years later, New York is still grappling with the serious and lasting impact of the attacks. But because of the Bush administration’s vague accounting, we do not know how much money we have actually received to date. The total amount of money we will eventually receive is also far from clear.

Unfortunately, it is clear that New York State’s own poor decisions have made it even harder for New York City to get what it needs from Washington.

SHORTFALLS IN 9/11 AID

The Bush administration is required by law to produce a full accounting of this 9/11 aid. Why it has failed to do so adequately is extremely difficult for me to understand. Along with members of the New York Congressional delegation, I have urged the administration on seven separate occasions to detail when and where recovery funds have been used and to clarify what has not been sent to New York from the President's initial pledge.

In late May, the White House Office of Management and Budget finally produced an attempted accounting document, but it can be called an "accounting" of 9/11 aid only by Enron standards. There is inadequate detail on where specific funds went for what purposes. In several instances, we don’t know when, if ever, these funds were used.

The document does not address the $268 million lost to wrongful taxation of 9/11 aid to downtown businesses. It also fails to explain how the administration intends to respond to billions in losses to our region that, at present, remain totally unaddressed. For example, city and state tax revenues lost as a result of 9/11 are estimated at $8.8 billion, for which the federal government has provided no assistance.

Nor does it account for a shortfall of about $2.6 billion in “Liberty Zone” Tax benefits.

“Liberty Zone” tax benefits made up fully one-fourth of the overall aid package, or about $5 billion, earmarked for New York's recovery by President Bush. These were intended to stimulate economic activity in Lower Manhattan. Now, most officials agree that $2.6 billion Liberty Zone benefits will go unused if Congress and the President fail to extend the deadline for when these benefits can be used, or alter how New York City can take advantage of the funds.

Significant gaps in the federal response have made achieving a full economic recovery for New York a serious challenge. From the widest perspective, costs and losses from 9/11 total between $80 billion and $100 billion while federal aid designated for the region remains under $20 billion and insurance payments are estimated to be between $30 billion and $40 billion. This leaves New York alone to shoulder the burden of between $20 billion and $50 billion in losses, in addition to ongoing costs for anti-terrorism security measures, unanticipated long-term health costs from the disaster and increasing costs for rebuilding projects in Lower Manhattan.

NEW YORK STATE’S POOR DECISIONS

The city’s financial problems go beyond those surrounding the president’s $21.4 billion, however. Seeking additional help from Washington is made more difficult by poor decisions on the use of existing funds by New York State.

For instance, rather than using current Liberty Bonds for their intended purpose, to help downtown redevelopment, Governor Pataki's administration is diverting $400 million for a power plant in Queens that is opposed by the community. This, even though Congress has said specifically that "public utility property and residential property located outside [Lower Manhattan] cannot be financed with the bonds."

Because the Governor has left us no choice, I have joined several elected officials in a lawsuit challenging this misuse of the Liberty Bonds. Federal legislators from around the country will be much less likely to support future requests to help New York's recovery if we don't spend existing resources the way they were meant for use by Congress.

THE FUNDS WE HAVE GOTTEN

Billions of dollars have come in for the redevelopment of the World Trade Center Site and transportation projects throughout New York City. But a significant portion of the pledged funding that we received has only come after a tough fight by the New York congressional delegation. The good news is that after our sustained efforts, there are a number of successes to report:

- $90 million for the health screening of sick and injured Ground Zero responders

- $80.5 million for New York's school system to make up for lost instructional time resulting from the terrorist attacks

- $33 million for the mental health needs of students affected by the disaster

- $10 million in federal aid for universities damaged by the attacks

- The extensive reform and expansion of Federal Emergency Management Agency's emergency response programs, leading to thousands more New Yorkers made eligible for individual grants and housing assistance after 9/11.

Hopefully, our continued advocacy in Washington for New York's remaining recovery needs will lead to additional successes, but we will need a united front, including the governor and the mayor, to achieve much needed and more positive results.

Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney represents the 14th District in New York, which includes parts of Manhattan and Queens.

Â

Tourism and Jobs

|

|

After four years as a jet-setting consultant in the financial industry, Ryan Zenga grew weary of traveling so much for his job, tired of the rude hotel clerks and snippy flight attendants. So he quit his high-paying job and enrolled in graduate school to follow his bliss.

But some of his friends were baffled when they learned what that bliss was: He is pursuing a master’s degree in tourism.

"You’re studying to be a travel agent?" people kept asking.

Poor service or no, Zenga sees tourism as the industry of the future. "People will always travel," he said.

Right now, they are traveling more and more to New York.

Last month, the number of visitors to the city reached pre-September 11 levels for the first time. Hotels are filling up, sites like the Empire State Building are drawing record numbers, and even foreign visitors, who dropped off most drastically in recent years, are returning.

That is why the city, like Zenga, is making tourism a major focus of its future economic development.

In March, Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced a $1.4 billion plan to expand the Jacob Javits Convention Center on the west side of Manhattan.

"This is about more than just tourism," Bloomberg said. "It's about our future and making sure that future means jobs for New Yorkers, and opportunity for everyone up and down the economic ladder."

As summer begins and more visitors wander the streets, guidebooks in hand, some New Yorkers wonder: do all these gawking visitors really translate into jobs – and the kind of jobs that residents want and need?

|

|

A BRIEF HISTORY OF TOURISM IN NEW YORK

Tourists first started coming to the city in large numbers after 1820 — and providing jobs for New Yorkers — when transportation became faster and cheaper, according to the Encyclopedia of New York.

By the beginning of the 20th century, electric bus tours zipped visitors around Manhattan and Brooklyn. In 1931, one million people paid a dollar to ride to the top of the Empire State Building. Grasping the potential, the city created the first agency to promote tourism, the New York City Convention and Visitors Bureau in 1935. By 1945, the Circle Line boats began their sightseeing excursions.

A decade later, tourism had become a major industry and officials actively marketed its image, eventually birthing slogans like "Fun City," "Big Apple," and "I LOVE NY."

However, there have long been tensions between New Yorkers and visitors.

If Thomas Jefferson wasn't exactly a tourist in 1790 when he expressed relief at leaving a place he called a "sewer of all the depravities of human nature," his sentiments persist to this day."I went to "Wonderful" New York recently," one visitor wrote on a website recently, "If one more [person] at the [South Street] Seaport asks me to buy a watch I'm gonna shoot them." The web site is called I HATE NYC

New Yorkers are happy to return the feelings, complaining about tourists stopping on the sidewalk for no apparent reason, overruning neighborhoods, driving up prices, and wearing really unhip pastel clothing.

"It’s reached a point to where I don’t go out to lunch," said John Sweeting, a lawyer who works a block west of Times Square. "To avoid the crowds, I bring my lunch and hide in my office."

BOOM TIMES ARE BACK

New York City officials, though, are happy to see them back. The industry had peaked in 2000, then crashed in the months after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Approximately 30,000 people who work in tourism lost their jobs.

Now nearly three years after the attacks, many of the economic signs point toward better times ahead.

This year, New York City expects 36.6 million people to come from out-of-town and to spend more than $15 billion, reaching record highs. New York’s occupancy rates are second in the nation (after Washington D.C.) with 87 percent of all rooms filled. And even foreign tourists, who spend four times more than domestic travelers, are returning lured in part by a weak U.S. dollar.

"We have pretty well recovered from September 11, with the exception of lower Manhattan," said Chuck Hunt of the New York State Restaurant Association. "Look at the New York Times Sunday job ads and you will see four or five columns of restaurant-related ads every week."

September 11 may have also changed the relationship between New Yorkers and tourists.

"New Yorkers had the attitude that if you don’t come to New York, you’re too dumb to be worth having," Jonathan Tisch, the CEO of Loews Hotels and chairman of NYC and Company told Newsday. "In an ironic way, 9/11 woke up a lot of people to the importance of tourism because of the substantial drop-off."

In turn, many people who had long been suspicious of New York turned sympathetic.

Gudryn Bilas, a tourist from New Zealand, said her view of New Yorkers improved after 9/11 and when she arrived, they turned out to be even friendlier than she previously thought. "People see me looking at my guide book and keep stopping to offer directions," she said, as she twirled it every which way, as if deciphering an ancient text, in City Hall Park.

WHAT DO TOURISTS REALLY BRING TO THE ECONOMY?

Tim Zagat, publisher of the Zagat’s Survey, once described each tourist that visits the city as "carrying a little wheelbarrow full of cash to put in the pockets of New Yorkers."

But while the tourism industry is critical to the local economy, some experts say that its overall impact — and the number of jobs tourism creates — is relatively small given the size of New York.

The biggest employers in the city are still finance, insurance, real estate and health care. Even with all of the growth in recent years, tourism-related jobs only still represent about five percent of the city’s total jobs. (By contrast, the health care industry employs 14 percent of the city's workforce.)

The real benefit of tourism is how it supplements New York’s existing economy. New Yorkers also eat at restaurants, go to Broadway shows, and visit the Met, but visitors help boost these businesses and improve the quality of the experience for everyone.

"If tourism dropped off a cliff, the cityâ€s economy would suffer," said Jason Bram, an economist for the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. "But it would not the same as if it happened in Orlando or Las Vegas where the whole economy is built around tourism."

WHAT KINDS OF JOBS DOES TOURISM CREATE?

About 230,000 New Yorkers already work in tourist related industries.

Tony Daniel, who runs a hotdog pushcart on Cedar Street in lower Manhattan, is one of them, and he loves tourists.

"Most people, when they come to me, they let me know they're from somewhere else, and they say they've heard about New York City hotdogs," he said. "I try to make them happy. If I can make them happy, then I’m happy because I make money, and that’s what it’s all about."

The bulk of jobs that the tourist industry creates, economists say, are low-skill and low-paying jobs.

According to Crain’s New York Business magazine, the average annual salary for the most available tourism related jobs include:

- Restaurant workers who earn $20,000 (not including tips)

- Retail workers who make about $25,000

- Museum and gallery employees who earn around $35,000

- And hotel workers who make about $40,000.

And while tourism can provide much needed jobs for some who have been laid off from other areas — like manufacturing, which has seen steep declines in recent years — the skills do not always translate.

"A cleaning person can move from one job to another," said Bram. "But someone who loses their job sewing in the garment industry can not necessarily make the transition to hotels or restaurants."

But Lilia Rach, associate dean at the New York University School for Hospitality, Tourism, and Sports Management where Ryan Zenga studies, says the industry gets unfairly stereotyped as only creating entry-level jobs.

"It’s a fallacy that has gained mythic proportions," said Rach, who says she has seen a recent increase in students leaving other successful careers to join the tourism field. "There are scores of mid- and upper-level positions."

Rach points toward to companies like American Express, which bills itself as the "world’s largest travel agency" and employs about 5,000 people in New York City. The number of jobs in the hotel industry, which provides some of the higher paying jobs, including some union jobs, grew by 25 percent in the 1990’s.

"My students see an industry that promotes people, that values creativity, and they see how New York City has reinvented itself through tourism," said Rach. "And it’s definitely an area that is hiring."

WELCOMING CONVENTIONS

In an effort to create more tourism-related jobs, Mayor Michael Bloomberg recently outlined an aggressive plan to double the Jacob Javits Convention Center and create a new convention, sports, and business district on the west side of Manhattan.

Many business leaders in the city have long argued that the convention center needs to be bigger. Although the city has the highest convention attendance of any city and is the second most popular convention center, for decades, officials have said the city loses out on dozens of more lucrative events because Javits is too small.

The mayor’s plan has been overshadowed by the debate over a stadium for the New York Jets that is also part of the plan. For 17 days a year, the stadium would be used for football games and other sporting events and concerts. The rest of the time, it will be a mid-size convention center, like the one in St. Louis.

Bloomberg said that the whole project would create 42,000 temporary construction jobs and 17,500 permanent new jobs.

"It will mean an end to seasonal layoffs in New York City's hotel industry forever," said Peter Ward, manager of Local 6, the hotel and restaurant employees union .

But watchdogs on both ends of the political spectrum question the grand predictions.

"All of the statistics about the projected benefits are overblown and exaggerated," said Jonathan Bowles of the Center for an Urban Future. "It is uncertain that this plan will lead to considerable new business for Javits."

For the Javits Convention Center to be really successful and to create new jobs in the hotel and restaurant industries, Bowles argues, New York must draw conventions made up of out-of-town visitors, not just people who live in the region. And the costs in New York – where the average hotel rate is over $225 a night - are too high.

Dozens of other cities have also expanded their convention centers in recent years, including Philadelphia, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Few of these cities have realized the profits and visitors that they had hoped. Boston, which recently opened its $800 million new convention center, had hoped to draw 38 new conventions in its first year; so far it has only booked three.

Plans for 40 other such convention projects across the nation are also underway, even though there is no evidence that the convention industry is growing.

"How can New York City officials justify spending $1.4 billion to nearly double the size of Javits?" wrote Steve Malanga of the Manhattan Institute wrote in a New York Times op-ed. "Actually they are using the same argument that officials everywhere else have made to justify their white elephants; claiming that their convention project will somehow work better than those of other cities."

RESCUING OR RUINING NEW YORK?

Tourists present a dilemma for New York City and its neighborhoods: visitor’s money and the jobs they produce are desirable, but the crowds, chintzy stores, and higher prices at restaurants aren’t.

In the 1990’s Rudolph Giuliani made a big push to make the New York more visitor friendly, fashioning Times Square as a model for other places in the city. Giuliani shut down sex shops, cleaned up graffiti, and welcomed large chain stores from suburban malls to set up shop. Although many New Yorkers liked feeling safer and seeing less garbage, they complained about the "Disney-fication" of city streets.

One of the primary quality-of-life issues for neighborhoods like Greenwich Village is the noise, crowds, street vendors, and other activities that come along with tourism. The neighborhood's population can multiply numerous times on a nice summer day.

The phenomenon repeated itself elsewhere, prompting Kathryn Freed, a former council member from Lower Manhattan, to once lament that SoHo had become "a giant amusement park… and the tourists don’t even throw us peanuts."

Harlem, in particular, has seen both sides of the issue.

The neighborhood has long attracted busloads of visitors who cruise up and down 125th Street or eat a meal at Sylvia’s, but also quickly get back on the bus to go back to midtown for their hotel and shopping. But when the125th Street Business Improvement District was formed in 1993 to help organize local merchants and help turn tourism into profits, it was seen by some as a sign of gentrification.

Still when it comes to how much the city spends to promote itself, New York is not Las Vegas. The desert gambling mecca spends about $190 million a year to promote tourism. By contrast, New York City and Company, the city’s official tourism bureau, has a budget of just $14 million.

Despite the contradictions tourism can create, other neighborhoods like Chinatown and Lower Manhattan are launching new marketing efforts with events, websites, and "neighborhood brands" in the hope that tourists will create jobs for residents.

In February, Brooklyn opened its first tourism and visitors center in Borough Hall as a way to help lure people out of Manhattan. Although it is too early to see specific results, officials said, they are pleased that they haven’t received big complaints either.

"So far we have no reports of crowds of tourists taking over a neighborhood," said Michael Kadish, a spokesperson for Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz. "We haven’t become the Village."

Related Articles:

Tour Guides

Selling New York

Shopping Industry

Everyone Loves NYC, For Now

Related Links:

Association for a Better New York

Hotel Association of New York

NYC and Company

New York State Hospitality and Tourism Association

New York State Restaurant Association

The Mayor's Latest Budget: Political Expediency, Future Deficits

The mayor’s latest budget, Glenn Pasanen argues, has “an ad hoc, last-minute quality” that once again promotes political expediency (and future deficits) over any long-term planning or strategic vision.

Tax Cuts and New York City

|

|

On a recent day at City Hall, Mayor Michael Bloomberg presented his annual $46 billion budget in the Blue Room on the west end of the building, while City Council Speaker Gifford Miller presented his budget in the Red Room at the east end of the building.

But when the two spoke about their rival tax cut plans, it seemed as if they had magically changed places.

The billionaire Republican Mayor Bloomberg sounded like a populist, accusing the City Council of catering to corporations and of neglecting the working people of the city.

"Somebody’s got to pay for the services," the mayor said, "and the truth of the matter is, the homeowners are less able than big business."

Meanwhile Democratic Speaker Miller sounded a lot like a Republican, arguing that a permanent, across-the-board tax cut for businesses and landlords would help stimulate the economy.

"They want a tax cut; they don’t want a check," said Miller. “They want to see their taxes go down.”

This year, New York’s budget battle has come down to tax cuts. Mayor Bloomberg wants to give $400 to each owner of a co-op, condo, and private house. Speaker Miller wants to reduce the property tax rate for all homeowners and businesses by two percent.

Despite their different approaches, the mayor and the speaker both start with the same basic assumptions about tax cuts:

- The tax cuts will reward those who helped the city weather tough fiscal times

- The tax cuts provide an incentive for residents to stay in New York

- They can help spur economic growth

And -- though not stated explicitly -- both officials clearly assume that the tax cuts will help get them elected in 2005.

However, many budget watchdogs argue that neither plan is particularly good for the city.

Can the city afford a tax cut? And do they really produce what politicians promise - or are they just a way to get votes?

THE RATIONALE FOR TAX CUTS

The theory of how taxes affect the economy, simply put is: If government taxes an item, it adds to the cost. As the price rises, fewer consumers wish to purchase the good and the quantity produced also decreases. The government gets the revenue from the tax, but both the consumer and the producer of the product bear the increased cost, and demand for the product will fall as a result.

The tax is not just a transfer of wealth from consumers and producers to the government; it is a permanent loss of economic activity to the whole society. This is why most economists agree that taxes reduce some of the incentive to spend, save, and invest.

At the same time, though, taxes pay for essential services that citizens demand from their government, such as schools, police officers, fire departments, and libraries.

While federal taxes have been instituted and rescinded in America since the mid-1800's, the notion of using tax cuts to "fix" the economy, experts say, is a modern one.

President John F. Kennedy issued one of the first major tax cuts designed to stimulate the economy, which was passed by his successor Lyndon Johnson in 1964.

Kennedy's plan instituted a new standard deduction, increased deductions for childcare expenses, and lowered taxes, including for those in the top tax bracket. The idea was that each dollar a person spent instead of paying taxes would go to another person who would spend it again. The plan used the immediate boost in economic activity to justify a government deficit. And the initiative is one that many economists point to as an example of successful tax relief. For a time, the national economy rebounded.

In local economies like New York's, tax cuts are often used to make a city more competitive with the surrounding area, and with other cities. New York City depends on an array of property, income, sales, and business taxes for revenue, and some argue that they affect people's decisions about where they work and live.

“There is some evidence that higher property taxes - all else being the same - are a factor in where people choose to live,” said Sanders Korenman, an economics professor at Baruch College.

However, one must also consider what those taxes are paying for. If taxes are cut, government spending must be cut as well.

"I don't mind paying my taxes because they fund valuable services like education," said Korenman. "You must look at taxes and expenditures together as a whole.”

Many people in the city point to the repeal of the commuter tax in 1999 as one of the worst tax cuts for New York City. State legislators in Albany eliminated the tax on people who worked in the city but lived in the suburbs as part of a political battle between the two parties over one upstate legislative contest.

The loss of the commuter tax costs the city $500 million a year in today's dollars - or enough money to pay for all of the city's parks along with all of its programs for senior citizens and for youth.

ARGUING THE PROS AND CONS

Once the discussion gets beyond basic economic theory, experts have wide and divergent views on whether tax cuts actually benefit New York City.

E.J. McMahon, a fellow of the Manhattan Institute, for example produced a study in 2001 concluding that 80,000 jobs - or one in every four new jobs in the city - had been created by local tax cuts in the previous five years.

“The lesson is clear: Tax cuts work,” wrote McMahon. “And in the years ahead, the best way to continue building New York’s job base will be to continue reducing its still-heavy tax burden – and by all means, avoiding adding to it.”

However, others, like James Parrott of the Fiscal Policy Institute see the same Giuliani era tax cuts as mistakes that helped create huge deficits for the future.

“I can’t think of any [recent] local tax cut that has made sense,” said Parrott.

Parrott argues that the way for government to create jobs and make the city more attractive is to invest in education, housing, and new development projects. “In general, what the city can do to stimulate the economy," he says, "is most often on the spending side."

Most voters, however, want it both ways. They want their taxes to go down. And they want good schools, roads without potholes, and a police force to keep them safe.

"There is a core belief in the American political culture that government should be small, but we also want services," said Doug Muzzio, a political science professor at Baruch College. "The public wants a free lunch."

POLITICAL PARTIES AND TAX CUTS

Today, the Republican Party presents itself as advocates for smaller government and lower taxes, while the Democratic Party emphasizes vital services like education and social services for citizens.

But this was not always the case.

The first federal income tax was issued by a Republican administration, during the Civil War. For decades, it was the Democrats who painted the Republicans as a high taxing, big spending party.

It was not until the 1980’s that the Republican Party made tax cuts a fundamental part of the party’s ideology.

President Ronald Reagan argued then that tax cuts could not only stimulate the economy, they could also shrink government while creating greater wealth for the nation. Economists still debate whether the Reagan cuts really led to boom times, or just created huge deficits.

Today, tax cuts are once again the rule of Washington, where Republicans control the presidency and both houses of Congress. President George W. Bush has continued the tax-cutting legacy, issuing plans for $330 billion in tax cuts over the next decade. Even growing deficits and the Iraq war have not deterred officials.

“Nothing is more important in the face of war,” House Majority Leader Tom DeLay said last year, “than cutting taxes.”

The national trend has even had a profound effect on New York City, a town where Democrats outnumber Republicans five to one -- and where just six years ago, there was another apparent ideological switcheroo in a fight over a tax cut: In 1998, Miller's predecessor, Democratic Council Speaker Peter Vallone, Jr., called for the elimination of a 12.5 percent surcharge on the personal income tax, which cost the city roughly $500 million a year. Bloomberg's predecessor, Republican Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, said the city could not afford it. The reasoning behind the plan was no secret: Vallone's aides said that the speaker needed a tax cut to attract votes in his race for governor. The tax cut went through, but it did not translate into a win for Vallone.

“Since the late 1970’s and 1980’s, the political notion that tax cuts can help the economy has become more prevalent,” said Marcia Van Wagner of the Citizens Budget Commission, a group that has advocated reducing taxes in New York. “It’s become the political theme everywhere.”

THE MAYOR’S AND COUNCIL’S RIVAL PLANS

Both Mayor Bloomberg and City Council Speaker Miller argue that their tax cut proposals will help stimulate the economy and return some of New Yorkers’ well-earned money.

Mayor Bloomberg wants the city to write a $400 check to all homeowners who had to pay the 18.5 percent property tax increase imposed in 2002. Business owners and landlords of large buildings would not be eligible.

City Council Speaker Gifford Miller wants to roll back property taxes two percent across the board, including for commercial property owners. A single-family homeowner with a $400,000 house would get about $50, and the owner of a condo of the same value would get about $125. In addition, Miller would eliminate the entire 18.5 percent property tax increase for senior citizens on fixed incomes.

But under Speaker Miller’s plan, the mayor charged, the average homeowner in Queens would get just $49, while Con Edison would get an $8 million tax cut. Miller responded with charges of his own, calling Bloomberg's plan a "Bush-style gimmick."

The mayor’s plan would cost about $250 million a year and would have to be approved by the State Legislature in Albany. The speaker's plan would cost $297 million, and the council could enact it with a simple majority of its own members, or 26 votes.

However, many budget watchdogs argue that neither plan is particularly good for the city.

While the city government has a surplus this year, it is expected to have a $3.7 billion deficit in the fiscal year that begins in July of 2005. Even the mayor admitted that if the economy and tax revenues returned to their highest levels in history – which is unlikely – the city would still not be able to close the budget gap in future years if costs continue as expected.

More fiscally conservative groups like the Citizens Budget Commission say officials should use the money to pay down some of the city's debt. In a letter to the mayor, the group said that although it supports reducing taxes in the city, that his plan was a "mistake" that "distributes the money in a way that is largely ineffective in promoting economic competitiveness."

Left-leaning groups like City Project want the money spent on education and social programs. "Any tax cuts at this point in time - whether proposed by the mayor or the council - are premature and fiscally irresponsible,” said City Project's Bonnie Brower.

NOT ALL TAX CUTS ARE EQUAL

While the political rhetoric often oversimplifies the debate over whether taxes are good or bad, budget experts warn that the public must carefully consider various issues when evaluating any tax proposal.

“It very much matters which tax you cut or raise, and how you do it,” said George Sweeting of the Independent Budget Office.

Who Gets the Tax Cut?

One consideration is whether a tax affects all people equally.

In the case of the city’s property taxes, many agree that the elected officials would do better to reform the current system than to issue pre-election tax cuts. In 1993, Mayor David Dinkins did an assessment of the property taxes and found that the system was "inordinately complex” and “poorly understood by taxpayers." Commercial real estate owners, multiple apartment landlords, and utilities pay much more than single-family homeowners.

“I have friends who own brownstones in Park Slope who pay next to nothing in property taxes,” said Van Wagner.

Who Needs A Tax Cut?

Another issue is who is most able to afford a tax increase.

Last year, for example, the mayor and City Council imposed a surcharge on personal income taxes for residents who make more than $100,000 a year and couples who make more than $150,000 a year based in part on the argument that they are more able to afford it. However, it could be argued that the sales tax – which also rose in both the state and city to a total of 8.625 percent in 2003 – is tougher on lower-income people.

“With any tax cut one must ask if this is being done to improve efficiencies, or if one party wants to appear to give money to one group or another,” said Korenman.

Does It Make the City More Attractive?

Also, various taxes may have the ability to make the city more or less competitive with surrounding areas.

The city, for example, has lower property taxes for individual homeowners compared with those in the suburbs, but the city also has several business taxes that make it more costly for companies to have their offices in New York.

Can the City Afford It? The most important measure is if the government can really afford a tax cut. And that is when the arguments circle back to the beginning.

Some would argue that if the city government cut spending and lowered taxes, that the whole economy and government would fare better. Others argue that tax cuts will starve essential services, making the city dirtier, more dangerous, and in general a less desirable place, inducing people to leave.

“No economist will argue that taxes do not affect an economy,” said McMahon. “The argument is over how much it affects the economy, and how that is offset by other spending.”

Whether or not Mayor Bloomberg’s or Speaker Miller's tax cut is approved this year, some warn that the city’s situation is growing more tenuous. Budget experts on all sides agree that the city’s long term budget situation – with growing debt, increased costs for health care, and increased labor costs – is troubling.

And a recent report by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York concluded that the city’s tax revenues are less reliable than they were 30 years ago because they rely heavily on income and business taxes, which are less predictable than property taxes. As the city’s economy rises and falls, the report argues, so will the government’s finances.

As in the past, that means that today's tax cut may soon be replaced by tomorrow's tax hike.

Related Links:

Citizens Budget Commission

City Project

Independent Budget Office

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Fiscal Policy Institute

Manhattan Institute

In Big Projects, Where Do The Jobs Go?

|

|

If Ikea has its way, the old maritime community of Red Hook will soon be home to the chain's largest store in the country. The massive furniture and housewares store could bring 9,000 cars a day to the area near the Gowanus Canal and will certainly change the character of the neighborhood. So as part of its pitch to sell throw pillows with Swedish names, meatballs in lingonberry sauce and birch veneer storage units on the Brooklyn waterfront, Ikea has promised jobs. On its Web site, Ikea pledges to create 500 to 600 new jobs, many filled by community residents. And the company says these are not dead-end, low-paying jobs but positions offering competitive salaries, health benefits and tuition reimbursements as well as training and growth opportunities.

The pitch has apparently convinced Dorothy Shields, a community activist and retired teacher's aide. "Hundreds of people need jobs," she told Newsday. "It will stop a lot of people doing things that are against the law."

The controversy over Ikea is being echoed throughout the city. With every new project put forth -- the West Side stadium for the Jets, waterfront development in Long Island City for the 2012 Olympics, the Nets arena in downtown Brooklyn -- the developers and the politicians that back them promise jobs. This is as it has always been, and, as in the past, it is an enticing prospect in a city with a current unemployment rate of 8 percent, more than two percentage points higher than the national level.

Such new projects are a linchpin of the Bloomberg administration's strategy to improve the city's economy and put its residents to work. Rather than focus on manufacturing or new industries such as biotechnology, the city has zeroed in on big events, such as the forthcoming Republican convention, and big projects. But do such projects really create jobs? If so, are local residents the ones who get them? And just how good are the jobs?

NEIGHBORHOODS TRANSFORMED, OR NEGLECTED IN A NEW WAY?

Seen from one perspective, East New York, the neighborhood in Brooklyn once called the murder capital of the city, was transformed into a kind of urban fairy tale, when 50 acres of rubbled wasteland became the site in 2000 of the Gateway Center, a new mall.

Related Companies and Blackacre Capital Partners spent $192 million to create the mall, which offers 640,000 square feet of stores, including Target, Old Navy, BJ's Wholesale Club and Babies R Us, as well as a new exit ramp off of the Belt Parkway. The mall, developers claimed, created 1,700 permanent jobs.

Supporters of this project and others like it say that they create revenue and provide a magnet that can lure potential customers to a neighborhood where they will patronize older businesses along with the new mall.

"It's a no-brainer. The city gets net new jobs without thinking twice about it," says Patty Noonan of the Partnership for New York City, a research and advocacy group composed of business leaders. While construction brings noise, dust, dirt and closed sidewalks, such inconveniences are "all signs that people want to live and work in these places. They're generally positive economic indicators," Noonan says. And she says some new projects can create prized office jobs as well as retail and food service position. They "provide the cutting-edge space that companies want," she says.

For others, however, the signs do not bode so well. Corporations get huge tax breaks, but do not always create all the jobs they claim they will. And while a new project might generate revenues, the money goes straight to the city, not necessarily to the neighborhood most affected. Many new big box stores and malls are occupied by out-of-town business that may offer the best jobs to suburbanites and give the poverty-wage work to city dwellers. All this can leave some residents feeling trampled.

New York City Councilmember Charles Barron, whose East New York district includes the new Gateway Center shopping mall, says the jobs created have hardly been worth the hype and inconvenience for area residents. "The jobs offered are entry-level, minimum-wage jobs," he says. "The management positions go to people outside of our community, to white people."

DO BUSINESSES DELIVER ON THE JOBS THEY PROMISED?

Statistics from other projects provide reason for skepticism about some of the businesses' claims. State Comptroller Alan Hevesi released an audit in March that showed businesses do not always deliver the jobs they say they will. The audit, which did not cover New York City, examined the effectiveness of the Empire Zone program, the state's plan to foster economic development in poor areas by giving businesses special tax breaks and other incentives. Hevesi's staff examined 375 businesses and found that they had created a total of 2,380 fewer jobs than they estimated they would when they applied for the program. In fact, almost a quarter of the businesses surveyed had actually cut workers. And in many cases, the companies received tax breaks that far exceeded the benefits, including new jobs, that they provided for their communities. In fact, the report said, 34 businesses that cut workers "apparently improperly claimed certain tax breaks totaling approximately $2.4 million."

Administrators of the Empire Zone program say that Hevesi's office ignores that fact that the size of the tax breaks is usually determined by the actual number of jobs created, not the projected figures. But some businesses made up numbers or did not report at all, and the state does not always check the figures, a 1995 state comptroller's report found. This means that numbers of estimated new jobs, as well as some accounts of actual jobs created, are as diaphanous as a spider's web before a raging rhino.

To address similar problems in New York City, the City Council in 1993 enacted a law that requires the Economic Development Corporation to report on the tax abatements, low-cost loans, and other financial incentives it gives businesses. Aimed more at companies that get benefits from the city for retaining, rather than creating, jobs, the law directed the development corporation to issue a report every year on deals that are worth over $250,000 or that cover preservation of at least 25 jobs.

In a 2001 analysis of seven such reports, the Independent Budget Office found that the reporting law had not accomplished what it set out to do. In fact, the annual reports regularly understated the cost to the city of job retention arrangements and exaggerated the positive effects. Although it did not mention specific companies, the budget office also found that some data was unreliable because it does not have to be verified. "Firms appear to be under no obligation to live up to their jobs created' projections in order to maintain the benefit received," the budget office found.

WHO GETS HIRED?

Development projects spawn temporary construction jobs as well as permanent positions. Rebuilding Lower Manhattan, for example, is expected to generate 10,000 construction jobs each year for the next 13 years. World Trade Center leaseholder Larry Silverstein has pledged to make sure that construction contracts go to minority- and women-owned businesses, which have long been underrepresented in their contracts with the city.

But not everyone takes special steps to ensure that those who need jobs wind up getting them. National chains often bring in outside workers for construction jobs and some management positions, says Perry Winston, architectural director at Pratt Institute Center for Community and Environmental Development. "National firms have national constituencies, or regional firms have regional constituencies, for hiring retail as well as construction. It's hard for them to come in and determine who is a good local contractor," explains Winston.

And many of the businesses at Gateway are from outside the area. The center had three spaces for family-style restaurants. But owners of the local 280-seat Lindenwood Diner (where John Gotti used to confab) felt left out. "All of these big restaurants are going in and we were never offered anything," owner Nick Tsakonas told the Daily News. "We've been in this community 32 years. We have over 60 employees. Everybody knows us. We're very upset. We've been trying to contact them, but we can't seem to get anywhere." Instead, the restaurants in the mall, such as Olive Garden and Red Lobster, are nationally owned chains that can fork out high rents of $30 per square foot.

LOCAL JOBS FOR LOCAL PEOPLE

But even when national chains operate the businesses, local residents can get the jobs. In 2002, the construction of the Time Warner Center, a glass and steel behemoth on Columbus Circle, was wreaking havoc with 3,000 construction workers raising noise and dust.

So New York City Councilmember Gale Brewer thought her constituents should get some jobs in return. Every week for six months, city and state officials, as well as general contractors, building management and shop owners met regularly to coordinate outreach and hiring procedures.

As chair of the City Council's technology committee, Brewer helped put together a web site that job-seekers could use to find jobs in the building. Time Warner Center's managers, Related Management Companies (subsidiary of Related Companies, developers of both the Time Warner Center and the Gateway Center), footed the bill for the web site.

The businesses were hesitant at first. "They were scared," Brewer says. "The private sector doesn't trust the government. . . They thought, "Why should we work with them?'"

One reason was that the city offers consulting services on regulations mandated by Equal Employment Opportunity, the Disability Act and other laws. The luxury Mandarin Oriental Hotel, for example, canceled its contract with a private company that advised them on these issues, says Brewer, "when they found out the city could do it for free."

Much of the effort focused on the Mandarin Oriental Hotel, which had been bombarded with job seekers. The city Department of Small Business Services narrowed down the 6,000 applications to about four for each open position and passed them on to the hotel's human resources department, which did the hiring.

In the end, nearly 70 percent of the 389 new hires at the five-star hotel were from New York City: 90 Manhattanites got jobs. Brewer estimates that her constituents from the West Side made up 20 percent of all those hired. Mandarin also brought on hotel and restaurant workers, including former Windows on the World staff, who had been displaced by the September 11 terrorist attacks.

The entire process was a first for the city, and the city hopes to replicate it in all five boroughs. With the Fulton Fish Market slated to relocate to Hunt's Point by the end of the year, the Department of Small Business Services is working with the area's economic development corporation, community-based organizations and other parties on outreach, hiring and training of new employees.

THE QUALITY OF JOBS

The lowest paying hotel job at the Mandarin pulls in about $16 per hour, plus benefits. That is because in New York's hotel industry, workers are unionized.

Early on, Mandarin signed a neutrality agreement with the Hotel Trades Council, an umbrella group for the city's nine hotel workers' unions. "Management was very cooperative. It is an agreement, and they kept their end," says union spokesperson John Turchiano. "Rather than getting into any types of fights, they said it's smart business." In return, workers got full medical coverage, pension plans, family benefits, access to scholarships and a legal fund, and salaries ranging from $30,000 to over $100,000 a year.

Not all the jobs at the Time Warner Center are as good. Whole Foods, for example, opposes having a union represent its employees.

And whatever the success of the effort at the Time Warner Center, other communities have had a more difficult time. In 2002, for example, residents of Canarsie, another neighborhood near Gateway, complained that they were not being notified of job openings at the center. "My impression is that Canarsie is being left out and shut out again," Reverend Matteo Rizzo of the Informed Voices Civic Association said at a community meeting.

And Barron says that what happened on the West Side of Manhattan, he says, is "not what happens in communities of color. We do meet with everybody, we make those demands," but still do not get good jobs. “I’m not demeaning anybody’s labor, but these are entry-level jobs,” says Barron. It might be more tolerable if at least the store was owned by a local entrepreneur. But when the owners are out of state millionaires, it raises his ire.

"There's a difference between economic development and economic exploitation," he continues. "When you give a corporation a tax break to hire us on a minimum wage basis, that's straight up exploitation."

Workers in some Home Depots have complained of salaries of only $10 to $12 an hour and say they do not get overtime pay that they are entitled to.

Whatever their failings, the big corporations may offer better salaries and benefits than small neighborhood businesses. One assistant manager at the Home Depot in Gateway Center told the New York Times, "It's a good thing to be able to get a job right here in the neighborhood, a job with benefits, not some mom and pop place way off in the city." His boss told the Times that of the 248 jobs filled at Home Depot, 200 hailed from around East New York.

But the question is whether government and business can do more to create better opportunities for the residents. "Of course [the new projects] are going to create jobs," says Bettina Damiani, project director of Good Jobs New York, which tracks corporations receiving tax breaks. "The real issue is what's the quality of those jobs. Do you create job ladders and training? There's not a citywide policy that would guarantee those things would happen."

The City Council's Alternative Budget Choices

The New York City Council's responseto Mayor Michael Bloomberg's preliminary budget offers a refreshing display of alternative budget choices. After releasing his cryptic, status-quo plan in January, the mayor has mostly left the budget stage to the council. And since both the council and the Independent Budget Office's March report say there are substantially more revenues available for next year than the mayor indicated, the council has taken the initiative to find new ways to spend the money.

The council also adds a broader vision, to address the city's always fragile revenue base, though their proposal is politically naĂŻve.

$1 Billion More To Spend, Council Says

The core of the council's alternative plan stems from its projection that tax revenues this year and next are much higher -- $900 million higher -- than the mayor's projection. (The IBO report projects $667 million in higher tax revenues over the two years.) For fiscal year 2005, the council comes up with over $1 billion in anticipated new revenues ( the added tax revenues, plus some new agency cuts and rejection of the mayor's $250 million property tax rebate to homeowners). The council proposes spending the bulk of this new money this way:

· $97 million: New spending initiatives, mostly to reduce class size and increase library hours

· $292 million: Restorations of mayor's cuts and enhancements

· $145 million: Funding private bus franchises

· $344 million: Tax cuts, primarily $236 million for a two percent property tax cut

Rainy Day and Surplus

The council, like the mayor, is taking a generally conservative fiscal position, promoting budget reserves and budget surpluses. For instance, the council would take another $100 million to create a "Rainy Day Fund," an emergency fund for tougher times. And it would support a $374 million surplus for 2005, on top of the mayor's projected $650 million surplus, creating more than a $1 billion surplus at the end of fiscal 2005. (The IBO estimates this fiscal year will end up with a $1.6 billion surplus.)

Reducing Class Size, Increasing Library Hours

Two plans make up most of the council's $97 million in initiatives. Reducing class size in kindergarten to third grade (from an average of more than 21 to 20) takes $38 million, and restoring at least 6-day service for all libraries (and 7-day for some) would cost $30 million.

Restoring Cuts

The $292 million of restorations are primarily a response to the "hidden cuts" that the mayor failed to acknowledge in the preliminary budget. These are mostly ongoing programs supported by the council that the mayor does not "baseline," (i.e., he drops them out of the budget) for subsequent years. This obfuscation constrains the council and confuses the public.

Among the council's major "restorations/enhancements" are:

$20 million in aging,

$11 million for youth employment,

$34 million for youth services,

$12.5 million for cultural affairs,

$2.75 million for legal services,

$59 million for child care (including $10 million for child care slots and nearly $9 million for preventive services), and $5.3 million for housing.

Tax Cuts

The council's $344 million tax cut plan sets up a challenge to the mayor's proposed one-shot property tax rebate for homeowners, but given the reality of the $3 billion tax increases in this year's budget, the overall fiscal impact of either plan will be minimal.

What does distinguish the council's plan is its targeting of tax relief to lower-income seniors and working families. Some 140,000 senior homeowners would see their 18.5 percent property tax increase wiped out. And 40,000 senior renters would get some relief through a tax abatement for small-building landlords. Moreover, the council once again proposes a small city-funded earned-income-tax credit for working families (costing only $11 million), 75 percent of which would go to families earning under $20,000.

The most expensive ($236 million) part of the council tax-cut plan, however, is its "permanent" across-the-board two percent cut in the property tax rate. Unlike the mayor's plan, and assuming that renters would get some kind of pass-through savings from their landlords, everybody would get at least a nominal benefit.

Both the mayor and council's property tax-cut proposals illustrate how such marginal changes only add complexities and inequities to the city's property tax system. The IBO's March report, for instance, shows the mayor's stated purpose - relieving 420,000 house owners and 180,000 co-op/condo owners of their 18.5 percent property tax increase - doesn't work equally, given the bizarre nature of assessment practices. Most house owners would get a rebate of about $50 more than their 18.5 percent increase, while most co-op and condo owners' rebate would be significantly less than their 18.5 percent increase.

The council adds a couple of other marginal wrinkles to this dysfunctional property tax system. It proposes an $11 million "deepening" of the property tax abatement currently enjoyed by co-op and condo owners, a council attempt (ongoing since the mid-1990s) to equalize tax burdens among homeowners. This would benefit some 65,000 lower-valued co-op and condo units by raising their abatement from 17.5 percent to 25 percent of their property tax.

The other wrinkle flirts with the council's old reputation for comic irrelevancies: $5 million for a property tax credit for homeowners who prune city-owned trees in their neighborhood.

Commuter/Reverse Commuter Tax

The council has a more visionary, if politically unlikely, plan in its other revenue proposal, what it calls a Commuter/Reverse Commuter program. This would be a 1.1 percent tax on the income of 800,000 commuters to pay for services provided to them. (Until repealed by the state legislature in 1999, a 0.45 percent commuter income tax raised about $500 million a year.) Since there are 140,000 city residents who work in suburban New York counties, the "reverse" part is that the city would reimburse those counties for their services to those commuters at an equivalent 1.1 percent of their suburban salaries.

The city would use the net proceeds of such a commuter tax - about $1 billion a year - to pay for the debt service on bonds that would be issued for capital expenditures in the schools and for affordable housing. This money would leverage about $6 billion of education capital and $5 billion of housing capital. The council thinks 40,000 units of housing could be built, half of which (new and preserved) they would target to households earning less than $25,000 a year. The other 20,000 units would be new and targeted to households earning between $25,000 and $104,000.

But such a program would need to pass the state legislature, which has already rejected similar legislation in the past.

Glenn Pasanen, former associate director of City Project, teaches political science at Lehman College of the City University.

New York's Sports Economy

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Yankee third baseman Alex Rodriguez has yet to swing a bat in the stadium known as "the house that Ruth built," but already many in the city believe that the highest paid baseball player in the world is worth every penny of his $252 million contract.

The Yankees have already surpassed their record for annual ticket sales. Modell's Sporting Goods can't keep Rodriguez's number 13 jerseys in stock. And television ratings and cable and advertising rates for Yankee games are expected to skyrocket.

But it isn't just Yankee owner George Steinbrenner who is seeing dollar signs.

When A-Rod made a visit to City Hall, even Mayor Michael Bloomberg began calculating what the city's newest millionaire resident might mean for New York.

"It is true that Alex's salary, the taxes on that, are going to balance the budget for the next seven years," joked Bloomberg.

Sports are big business in New York. A city comptroller's report estimated that the sports industry is worth as much as the entire construction industry. There is even a city agency dedicated to sports and a commissioner charged with growing "a healthy environment for professional, amateur, and scholastic sports activities."

Sports are also driving some of New York's biggest plans for the future.

City officials are already working to build a professional basketball arena for the Nets in Brooklyn. Last week, Mayor Bloomberg put his full support behind a controversial plan for a $1.4 billion football stadium on the west side of Manhattan for the New York Jets - that would also be a key part of a bid for the 2012 Summer Olympic Games. (Read articles by Jets President Jay Cross arguing for the stadium and Joe Restuccia against the stadium.)

Politicians claim that these enormous projects will bring tens of thousands of jobs and billions of dollars to the city.

But critics counter that such economic predictions are wildly inflated. Much of the money goes to developers, player salaries, and media tycoons. Stadiums cost taxpayers millions of dollars. And those authentic A-Rod jerseys that cost $199 are not even made in the U.S., let alone New York.

Sports, they say, can make us cheer or jeer, but they don't do anything for the bottom line.

NEW YORK CITY - A SPORTS TOWN

While New York is often called the financial capital of the world and the media capital, the city can also make a case for being the sporting capital.

The city claims five professional sports teams within its borders:

- The Yankees baseball team

- The Mets baseball team

- The Rangers hockey team

- The Knicks basketball team

- The Liberty women's basketball team

Two minor league baseball teams:

And that is not including the teams associated with New York that play in New Jersey and on Long Island:

- The Giants football team

- The Jets football team

- The Metrostars soccer team

- The Islanders hockey team

Each major professional league has its world headquarters in New York. The city is home to huge annual events like U.S. Open tennis tournament and New York City Marathon. And every year, the city plays host to dozens of smaller events, like the Millrose Games track and field competition, the Big East college basketball tournament, professional cycling, and even "Man vs. Machine" chess, which featured a match between the top player Garry Kasparov and a computer.

City Hall officials estimate that the sports industry generates $11.5 billion a year, or 2.5 percent of the city's total annual economy.

"It is just a fact that sports play a significant part in the city's economy," said city Sports Commissioner Kenneth Podziba. "The reason we can host so many successful events is that we have an international fan base. New Yorkers are the most passionate and knowledgeable fans."

The New York Yankees - with their 26 World Championships - are the most lucrative sports franchise in the city, and arguably the most recognized sports team in the world. On any game day, the Yankees employ about 2,000 people.

In the past, the city comptroller's office has estimated that each time the Yankees make it to the World Series, it generates between $60 and $90 million for the economy, based on ticket and concession sales, media payments, and other money spent on restaurants and merchandise. The Yankees have made it to the World Series six times in the last eight years.

This week, the Yankees will try to expand their international appeal and boost tourism by opening their 2004 season in Japan, which is the most lucrative foreign tourism market for New York, sending more than 300,000 visitors a year to the city.

BOOING THE BOOSTERS

However, some budget watchdogs and experts say that the economics of sports often don't add up.

The biggest expense for most professional sports teams is player and owner salaries. (The New York Yankees have the highest payroll in baseball at $156 million a year, or three times the payroll of the Florida Marlins, who beat the Yankees in the World Series last year.) But most players do not live in the city - with rare exceptions like Mets first baseman Mike Piazza - and so they do not spend that much of their salaries in the city or pay local taxes.

"When the commuter tax was abolished [in 1999], we even lost our ability to tax players from the suburbs and from visiting teams," said Doug Tureskey of the Independent Budget Office, who estimated that, when the commuter tax was still in place, the city earned $500,000 in annual tax revenue from Mets and Yankee players and their opponents.

Also when the average Yankee fan pays $45 for a ticket, it is not really additional money being spent in the city, economists say. That money would likely have been spent at a restaurant, clothing store, or Broadway play anyway.

Sports often cost taxpayers and the city government long after stadiums and arenas are built.

For the last 20 years, Madison Square Garden has received a property tax exemption worth $12 million a year. Under city tax law, the tax break is given because major league hockey and basketball teams play there, and without it, the law reads, the "loss of the teams is likely."

Since it was implemented in 1982, it has cost the city more than $200 million.

Critics argue that such taxpayer subsidies are a waste of money, given that Madison Square Garden, L.P. - , which owns the Knicks, Rangers, the MSG and Fox Sports New York television networks, and Radio City Music Hall is a profitable company that did more than $772 million worth of business last year.

When one adds up the billions of dollars in taxpayers' money that goes to fund stadiums and arenas, the cost of police and sanitation, and delays from traffic congestion, economists say, sports has little or no effect on the local economy.

"By having a sports team or a new stadium or arena, you don't increase the level of per capita income, and you don't increase the level of employment," said Andrew Zimbalist, a professor of sports and economics. "There's no direct economic development of communities."

STADIUM POLITICS

Six dozen new ball parks, stadiums and arenas have been built in the U.S. in last 10 years. In many cases, the argument for funding the projects with public money was that they would help grow the economy, revive neighborhoods, and produce jobs.

But what often convinces the public and officials to spend the millions is the fear - one of the worst fears a sports fan can have - that their teams would repeat what happened in New York half a century ago.

In 1957, both the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Giants baseball teams left for California. Mayor Robert Wagner and other elected officials tried in vain to keep the teams in New York, even offering to build new ballparks. Many New Yorkers still mourn that day.

"When I was 12 years old I cried like a baby when the Dodgers left for la-la land," said Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz.

In the 1990's, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, a die-hard Yankees fan, pushed for a new Yankee stadium on the west side of Manhattan when owner George Steinbrenner said he might leave for New Jersey. Political opposition eventually killed the plan and the Yankees stayed anyway.

But Giuliani did not give up on his stadium quest, and he led the effort to build two minor league baseball stadiums, which opened in 2001. While the teams have been successful - the Brooklyn Cyclones have sold out 106 consecutive games - some in the neighborhood say they are still waiting to see the benefits on the local economy. (Read articles about the Coney Island and Staten Island stadiums.)

When asked why he did not put the minor league stadiums up for a public vote, Giuliani replied, "Because people would have voted it down. That's why you need a leader. Somebody who has some vision."

BLOOMBERG'S SPORTS AGENDA

Mayor Bloomberg - who wrote in his autobiography that he didn't care much for sports - has continued Giuliani's stadium vision, but in a different way.

Bloomberg hired Daniel Doctoroff, founder of the Olympic 2012 bid and part owner of the New York Islander's hockey team, as his deputy mayor of economic development. He also appointed former Yankee executive Joseph Perello as the city's official marketing director.

In January, the mayor quickly backed real estate developer Bruce Ratner, who placed the winning $300 million bid for the New Jersey Nets basketball and has plans to build a new basketball arena in downtown Brooklyn on Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues. (Read articles for and against the Brooklyn arena.)

And last week, Mayor Bloomberg and Governor George Pataki officially announced a $2.8 billion development proposal for the far west side of Manhattan that would nearly double the size of the Jacob Javits Convention Center and include a 75,000-seat stadium for the New York Jets. Officials said the expanded convention center and new stadium would help create more than 15,000 jobs for the city and provide more than 500,000 days of additional hotel stays per year.

"We are bringing the New York Jets home where they belong, and capturing millions of dollars a year and thousands of jobs now lost across the river," said Bloomberg, "[It will] make all of New York more vibrant and economically sound for generations to come."

If the stadium helps lure the 2012 Summer Olympic Games to New York, organizers estimate that the New York-New Jersey region could expect tens of thousands of new jobs and a local economic impact approaching $11 billion. (Read more about the Olympic bid.)

But the plan has steep costs.

The stadium would be financed with $600 million from the city and state, which would pay for the retractable roof and the platform over the rail yards. The Javits expansion would be financed by $600 million from the city and the state, and $500 million from a $1.50-per-night hotel tax. The extension of the number 7-subway line from Times Square to the far west side would cost $2 billion.

Response to the west side stadium plan has been mixed.

Many business groups support the plan, in part because they have long wanted more convention space, which Kathryn Wylde of the Partnership of New York, called the "single most important public investment that the city and state can make."

Several union leaders have endorsed the plan because it means jobs for construction workers and others.

Some elected officials like City Comptroller William Thompson are still examining the proposal, while some area business and neighborhood groups like the Hell's Kitchen/Hudson Yards Alliance vehemently oppose the plan. (See links to websites of groups for and against these projects.)

A New York Times editorial argued that while extending the subway line, creating parks, and expanding the convention center are all good ideas, the west side plan could also "leave the city with nothing but a football team playing on the river, more traffic congestion and a pile of new debt."

SOMETHING TO CHEER FOR