Budget Surplus Obscures Uncertainties

So many people are so optimistic about budget surpluses in the city’s budget both this year and next – the Independent Budget Office projects a $1.6 billion surplus for the current fiscal year, ending in June, and more than a $500 million surplus next year – that the mayor and the city council are bickering over not whether but how to cut taxes.

But in terms of basic city services, the budget prospect is far less comforting. City expenditures in the mayor’s current plan grow from $46.5 billion in 2004 to $52.3 billion, according to projections by the Independent Budget Office, which represents three percent a year. This, however, is misleading: Most city programs and services average only 0.4 percent growth per year. Several are actually losing funding over the next four years, among them youth services, aging, cultural affairs, children’s services, parks, and housing. Most of the growth in spending comes from mandated expenses for debt service, pensions, Medicaid, and fringe benefits.

This problem of flat or declining city-service funding is compounded by the persistence of longer-term budget deficits, an average of more than $2.2 billion a year from 2006 to 2008, according to the Independent Budget Office. One major cause of these shifting priorities and future deficits is the city’s roller-coaster approach to tax policy.

BUDGET UNCERTAINTIES

At the council’s preliminary budget hearing earlier this month, Ronnie Lowenstein, director of the Independent Budget Office, listed four uncertainties in the mayor’s four-year plan:

- the absence of any money for wage increases (each one percent increase in wages costs about $200 million)

- the dependence on new federal and state aid

- accelerating pension costs (perhaps $300 million more than the mayor’s projected $600 million increase in 2005)

- and (“a huge uncertainty”) the possibility that the city will have to bear a share of the anticipated new schools funding stemming from the Campaign for Fiscal Equity’s successful suit against the state’s education funding system.

School Aid

The campaign’s March 1 proposal for funding the schools(which they call a “work-in-progress”) suggests a statewide, fully-implemented plan to provide a sound basic education to all students would cost $9.5 billion more than is currently being spent, 49 percent of which ($4.7 billion) would go to New York City. The big unknown is how much of that $4.7 billion would come from increased city, not state, funding. The campaign’s own estimate (see page 27 of their proposal) would represent a 35 percent increase in city-funded per capita funding from the 2001-2002 year ($4,362 per pupil) to the fully-implemented year ($5,878).

State Takeover Of City’s Debt In Doubt

Several other uncertainties revolve around Governor George Pataki, his many public authorities, and the state legislature. The good news in early March was the decision of the state appellate division to approve the legislature’ s $2.5 billion five-year takeover of the city’s Municipal Assistance Corporation debt, a move the Governor has blocked. ($500 million of that deal is still part of this fiscal year’s budget.) The bad news was a state authority’s appeal of the decision to the state’s highest court.

State Aid, State Authorities

On another front, the projected $400 million in new state aid is, as always, a question mark at this point. The City Comptroller says half of the $400 million is at risk. But still another major uncertainty is how Governor George Pataki will help or hinder the city in a number of economic development and governance issues that, at least tangentially, can affect the city’s budget. A highly critical report on public authoritiesfrom the office of the state comptroller, Alan G. Hevesi, is a reminder of how secretive, self-serving, and unaccountable state authorities can be: “A culture of arrogance,” he says, “pervades these entities.”

Through one or another such authority, the governor controls the future of the World Trade Center site, the Javits Center expansion, Governors Island, and the Olympics/Jets/commercial West Side project. The style of such authorities was illustrated at a recent Baruch College Newman Institute seminar about the “Lessons of Battery Park City.” A founder and one of three current board members of the Battery Park City Authority proposed to fill in another 25 acres of the Hudson River at its north end and suggested the Authority take over all development in downtown Manhattan, including Governors Island.

BUDGET BALANCING

The mayor’s bold fiscal strokes last year have had a very positive effect on the current plan. The large budget surplus for this year and the smaller anticipated surplus for next year stem in large part from the property, personal income, and sales tax increases that the mayor proposed and, with modest changes, the council enacted in the last budget cycle. On the other hand, the mayor and council made the increases temporary, ignoring the chance to achieve structural budget balance, i.e., a long-term balance between revenues and expenditures.

Losing $1 Billion In Tax Revenues

As the new tax rates are phased out, the city will lose over $1 billion a year in tax revenues, most of it from the progressive personal income tax, where the cancellation of two top rates (4.25% and 4.45%, for couples making over $150,000 and $500,000, respectively) will sharply narrow the gap between rates for lower- and higher-income New Yorkers. The 4.45 percent top rate, incidentally, was the prevailing top rate for most of the 1990s, through both bad and good economic times.

The balanced-budget news has prompted competing tax relief programs between the mayor and council. The mayor wants to give up $250 million in property tax revenues through a rebate of $400 for co-op, condo, and house owners’ property taxes. That leaves out any relief for renters and business owners.

Council Speaker Gifford Miller announced a $300 million tax-cut package in his February 25 State of the City speech, including property tax relief for low-income seniors and the two percent across-the-board property tax rate decrease. The relief for seniors is progressive, and the inclusion of renters in the plan is more broad-based than the mayor’s plan.

But the council rate decrease is only two percent, and therefore the bulk of the property tax relief will go to larger commercial owners. And neither the mayor nor speaker’s plan addresses the existing complexities and inequities in the property tax system. House owners on average have a better tax deal than co-op owners, and co-op owners have a lower burden than condo owners. Worse, the average renter, who earns less than the average owner, carries a much higher burden than the average owner.

SHIFTING AWAY FROM SERVICE PRIORITIES

The financial plan’s comfort with technical budget balancing and the lack of any vision in the 2004-2008 financial plan means that the increasingly smaller share of city funding devoted to basic services goes unattended. Beyond the bickering over a tax-relief package, the mayor and council will apparently spend the spring fighting, as usual, over “hidden service cuts” – the hundreds of programs funded by council and borough president initiatives that are simply left out of any four-year plan because the mayor calls them one-year-only programs.

So while the mayor and council bicker into June over perhaps $400 million of tax relief and budget restorations, the longer-term shift in budget priorities unfolds as if inevitable. Most service spending is flat or declining, while overall expenditures grow from $46.5 billion to $52.3 billion. IBO figures show Medicaid and pension costs skyrocket in dollars and as a share of the budget:

• In 2004, Medicaid costs $3.4 billion, or 7.4 percent of the total budget

• In 2008, Medicaid costs $4.5 billion, or 8.5 percent of the total budget

• In 2004, pension costs are $2.4 billion, or 5.2 percent of the total budget

• In 2008, pension costs are $4.2 billion, or 8.1 percent of the total budget

In contrast, basic services lose dollars and/or shares of the budget:

• In 2004, education spending is $12.7 billion, or 27.4 percent of the budget

• In 2008, education spending is $13.5 billion, or 25.8 percent of the budget

• In 2004, police spending is $3.5 billion, or 7.5 percent of the budget

• In 2008, police spending is $3.5 billion, or 6.6 percent of the budget

• In 2004, children’s services spending is $2.6 billion, 4.9 percent of the budget

• In 2008, children’s services spending is $2.2 billion, 4.1 percent of the budget

• In 2004, aging spending is $224 million, or 0.48 percent of the budget

• In 2008, aging spending is $199 million, or 0.38 percent of the budget

All in all, it would be good if the mayor and council could temper their bickering and publicly address some of the larger uncertainties that their own budget and their own governor pose for them in coming months.

Glenn Pasanen, former associate director of City Project, teaches political science at Lehman College of the City University.

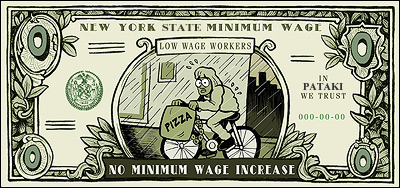

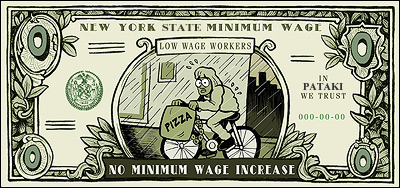

A Minimum Wage Increase Will Hurt Small Business and the Working Poor

The issue of increasing New York State's minimum wage is again receiving considerable attention in the state capitol in Albany. And at first blush, a lot of New Yorkers stopped on the street would probably agree with the general idea of putting more money into the pockets of the working poor. Even small-business owners may well think that putting more money into the hands of their poorer customers is a good idea. But raising the minimum wage is not the same as delivering more income into the hands of people with low-skill jobs.

The issue of increasing New York State's minimum wage is again receiving considerable attention in the state capitol in Albany. And at first blush, a lot of New Yorkers stopped on the street would probably agree with the general idea of putting more money into the pockets of the working poor. Even small-business owners may well think that putting more money into the hands of their poorer customers is a good idea. But raising the minimum wage is not the same as delivering more income into the hands of people with low-skill jobs.

In fact, it is a complicated issue with many potentially serious implications for the future of our state as well as our lowest-skilled workers. So, when something like a hike in the minimum wage is proposed -- something that sounds simple, intuitive and benevolent -- responsible citizens should still take a step back and ask: Who really pays for the increase? The answers may surprise you.

In 1999, New York hiked the state minimum wage to $5.15 per hour and permanently tied it to the federal rate. This placed New York State on par with every other state that links its minimum wage to the federal wage and eliminated the problems caused when competing states have differing wage laws. It leveled the playing field and placed the issue of a minimum wage where it belongs -- with the federal government.

Nevertheless, organized labor is now pushing hard for a $1.60 -- or 31 percent -- increase in the state's minimum wage, notwithstanding the competitive disadvantages for business that would come from leapfrogging the federal rate.

A higher minimum wage puts strong upward pressure on the entire wage structure, which is the real reason that unions support it. But as any first-year economics major will tell you, if you tax something (in this case, jobs) or increase its cost, you end up with less demand for that thing. Can a state with one of the most expensive business climates in the nation, that has 300,000 unemployed and has lost 100 manufacturing jobs a day for the past five years, afford a new round of generalized wage inflation? The unions ought to think this through more thoroughly.

Perhaps most surprising, though, is big labor's indifference to the question of whether or not a hike in the minimum wage would really help the working poor and whether we can afford its wider social and economic impacts. Research from Michigan State University, for example, found that increases in the minimum wage encourage more teenagers to leave school and enter the workplace, displacing lower-skilled workers from their jobs.

Raising the minimum wage will work to deprive the working poor of job opportunities. Those most affected will be single parents, developmentally disabled persons, school dropouts and recent immigrants with poor language and reading skills. If you price entry-level labor higher than its real value, jobs will not be available for people whose skills are limited.

Then there is the impact on small businesses, considered by many to be the engine of growth and opportunity in the American economy. A small increase of $1.60 per hour would cost a bake shop with ten clerks and bakers over $30,000 per year, not counting the increases that a higher payroll brings in the costs of workers compensation insurance, unemployment insurance, Social Security taxes, Medicare taxes and even liability insurance in some cases. This is money that most small employers simply do not have. So, what will they do? Lay off workers, increase prices, or both.

When you consider that businesses with fewer than 100 employees create the majority of new jobs in New York, and that small business has created about two-thirds of the net new jobs in the United States since 1970, the proposal to hike the minimum begins to look less attractive.

Small businesses in New York are struggling against a tide of steadily rising costs. To reverse this trend and stimulate growth and jobs we must work to reduce the costs of doing business. Increasing the minimum wage at a time when we can least afford it just adds to the problem.

Now, is the sky going to fall if New York increased its minimum wage? Would we see dramatic layoffs and skyrocketing unemployment overnight? Probably not. But given that state spending, debt and taxes are already too high, the increase would hurt.

The final reason for opposing an increase is that it is not necessary. New York offers a wide array of generous programs, like the Earned Income Tax Credit, that provide cash assistance to encourage people to work without the negative impacts of a hike in the minimum wage. Other assistance comes from the Child and Dependent Care Credit, the federal Child Tax Credit, the Home Energy Assistance Program, and the Real Property Tax Circuit Breaker. Health benefits are provided through programs like Child Health Plus, Family Health Plus, Healthy NY and Medicaid. Nutritional assistance comes from Food Stamps, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (popularly known as WIC) program, and school breakfast and lunch programs. A college tuition tax credit also aids low-income families.

In 2003, the state and federal earned income tax credit was worth $5,465 per year for New York families making no more than twice the poverty level, providing over $700 million to the state's working families and individuals. With the tax credit counted, the effective hourly wage for a single parent with two children is $7.77 per hour (well above the wage rate sought by the Working Families Party). Add in the value of food stamps, free school meals and health insurance and the effective value of a minimum wage job tops $14 per hour.

New York today generously helps its most needy residents -- and in ways that do not damage small businesses or destroy job opportunities for teens and low-skilled people. Goodwill toward those who are less fortunate than us is natural -- but it should not cause us to turn off our minds and end up spreading far more ill than good.

Mark Alesse and Matthew Guilbault are with the New York chapter of the National Federation of Independent Business, a nonprofit, nonpartisan group representing 20,000 small businesses in New York.

#####

Related Story

New York Workers Need A Raise

by Andrew Friedman and Fernando Ferrer

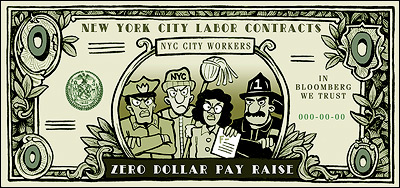

The City Budget and Labor Unions

When Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced last month that New York City's fiscal crisis was beginning to subside, he hailed the "heroes of this crisis" and said it was time to reward those who helped "get us through the last two years."

When Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced last month that New York City's fiscal crisis was beginning to subside, he hailed the "heroes of this crisis" and said it was time to reward those who helped "get us through the last two years."

But the "heroes" the mayor was talking about were not the police who saw their ranks decline by 4,000 officers nor the firefighters who worked to cover more neighborhoods after six firehouses closed - but taxpayers who own their own homes.

In his $45 billion budget, Mayor Bloomberg proposed a $400 property tax rebate for condo, co-op, and homeowners, but he said there was no money for pay increases for city employees.

"People will look and say there's lots of money in there for raises," the mayor said. "There isn't."

Every city labor union contract has expired, but Mayor Bloomberg says there can be no salary increases without concessions on work rules, benefit packages, and overtime and vacation policy. So far, the City Council, which has traditionally championed city workers, agrees with the mayor, and even offered to give out larger tax breaks rather than advocate for raises.

Labor leaders accuse officials of playing political games with the budget and ignoring the workforce that keeps the city running.

"Now is the time to invest in our public employees who have not let us down," said Brian McLaughlin of the New York City Central Labor Council. "Years of privatization and productivity schemes from City Hall have gotten us nowhere."

The outcome of these contentious negotiations between city government and labor have an impact not only on the city's fiscal health, but also on how the schools run, how clean the streets are, if crime goes up or down, and how long it takes to put out a fire.

THE CITY'S WORKFORCE AND COSTS

New York City employs about 286,000 full- and part-time workers. The full-time workforce is often divided into three categories:

- 96,000 teachers

- 64,000 uniformed employees - police, firefighters, corrections officers, and sanitation workers

- 80,000 "civilian" employees - all of the workers that do not fit into other categories.

In the last three years, in an effort to streamline government and cut costs, the city's workforce has decreased by 5 percent or 14,000 full-time positions.

But despite cuts, the city's overall labor costs have risen 20 percent.

The reason, say fiscal watchdogs, is that New York's overtime, benefit and pension packages are more expensive than elsewhere in the country and the costs continue to rise.

In 2003, New York City paid out $870 million in overtime, nearly double the total a decade ago. The average cost of a New York City worker is now more than $82,000 a year, including pay and benefits, according to one report (in pdf format).

"A significant part of the city's budget problem is caused by growing personnel costs," said Diana Fortuna of the Citizens Budget Commission. "The city will be continually forced to cut services if these costs are not curtailed."

In addition to the city's active workforce, New York also supports 180,000 people who have already retired.

Pension costs are the fastest rising share of the budget. According to the mayor's office, pension and fringe benefit costs rise 5 percent each year; by the year 2008, the city will pay $10 billion a year in pensions or about 20 percent of the annual budget.

WHAT CITY HALL WANTS

Since he took office in January 2002, Mayor Bloomberg has taken a fairly tough approach toward unions.

The mayor reduced the city's workforce. He threatened to jail MTA workers if they went on strike in December of 2002. And last year, he demanded $600 million in concessions from unions to help balance the budget, when they did not produce what he wanted, he blamed union leaders for tax hikes and service cuts.

"When you do something and help us, then afterward, you can get it back," the mayor told labor leaders.

The mayor's latest budget also proposes a new pension level for city employees that would apply to new employees. It would reduce cost of living adjustments, increase the age and service requirements, and require 10 years of work for city workers to become fully vested in the program. Such a program could produce a total of $10 billion in savings for the city between now and the year 2025, according to City Hall.

The New York City Council, which has no direct role in collective bargaining agreements, but must still approve the budget, generally agrees with the mayor, and has made tax cuts a priority.

"All city employees could use a raise, but unfortunately we are still in some financially difficult times," said Councilmember Joseph Addabbo, Jr., chair of the council's civil service and labor committee.

The City Council also has the power to bring certain labor issues into public view and help shape the negotiations - either by raising workers complaints or uncovering inefficient work rules.

Last fall, Councilmember Eva Moskowitz, who chairs the education committee, held a series of hearings on school employee work rules and helped bring to light how difficult it is to get rid of poorly performing teachers, a process that can sometimes take up to two years.

The union was angered by the council hearings, especially since the overwhelmingly Democratic members usually side with unions in disputes with the mayor. Still shortly after the hearings, the United Federation of Teachers released a plan to overhaul the disciplinary system for teachers, including calling for a task force of pro bono lawyers to clear the backlog of 200 teachers who still receive full pay while awaiting dismissal.

WHAT THE UNIONS WANT

While the mayor can point to rising costs and budget problems, city workers say new contracts and pay raises are long overdue.

Every city union contract - for teachers, police, firefighters, sanitation, corrections, and other workers - has expired. While this is not unusual and new contracts are agreed to retroactively, many workers feel abandoned by the city at a time when taxes, subway fares, and housing costs continue to rise.

Teachers

In June 2002, Mayor Bloomberg negotiated a new contract with teachers that his predecessor Rudolph Giuliani had put off. It included raises of between 16 and 22 percent depending on experience in exchange for working 100 extra minutes a week.

However, since then, relations between City Hall and the United Federation of Teachers have turned contentious.

Recently, the mayor proposed replacing the current 42-year-old, 200-page teachers' contract with an 8-page document that gives the city unprecedented control over educators and the classroom. Bloomberg's teachers contract would:

- Add more days to the school year.

- Bar teachers from doing union work during the school day.

- Eliminate sabbaticals teachers.

- Cut the number of unused sick days that can be cashed in by retirees.

- Give bonuses to teachers to work in low performing schools.

United Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten rejected the proposal and called it a "kick in the teeth."

However, teachers say it is not just about the details of work rules, but giving teachers the respect they deserve. The mayor, they argue, is making it more difficult to recruit and retain quality teachers.

Forty-five percent of all New York City teachers either quit the profession in their first five years or leave for a teaching position outside the city, according to the union. Currently, New York is having an especially difficult time recruiting math and science teachers. The poorest schools have the highest teacher turnover rates, which means those students are put at a further disadvantage.

Uniformed Workers

Contracts with uniformed services - police, firefighters, corrections, and sanitation worker - often follow a pattern; if one union gets a new contract, the others get agreements on a similar scale.

New York police officers, whose contract expired in July 2001, have long been seeking pay that is equal to officers in other places. The starting salary for a New York City police officer is $36,878, compared to $47,853 in Yonkers.

Like teachers, police officers say it is difficult to recruit and retain officers who can make much more in the suburbs. Police officers also stress the danger of their work - risking death while working for the city. In January, the Patrolmen's Benevolent Association unveiled a massive billboard near Times Square that read: "NYC Cops, ranked #1 in the nation in fighting crime - ranked #145 in the nation in salary: It's time to fix the injustice."

Last year, the city tried to broker a deal with correction officers union and its 9,000 members by creating longer shifts, but the deal fell apart when the city wouldn't put the money saved into pay increases. Like the police, correction officers point to the stressful and dangerous nature of their work.

"You want me to turn this entire municipal work force into a slave organization," said Norman Seabrook, president of the Corrections Officers Benevolent Association. "I don't think so."

In many ways the New York City Fire Department is still trying to rebuild the department after they lost 343 firefighters and a combined 4,000 years of experience on September 11, 2001. Last year, the city closed six firehouses in an effort to save money in the budget. Last week, the mayor agreed to increase the number of firefighters from four to five on additional engines. Union officials maintain that increased staffing is critical for ensuring the safety of firefighters and city residents.

"The difference between a five-man engine and a four-man engine is dramatic," said Stephen Cassidy of the union. "It actually takes twice as much time for a four-man engine to get water on a fire."

And the sanitation workers were angered when 217 workers were laid off for budget cuts. Those workers have now all been rehired and workers say they deserve raises and a new contract, which expired in October 2002.

Civilian Workers

City workers represented by District Council 37, which is the city's and the nation's largest union with over 125,000 members, feel particularly abandoned by the city.

The union includes many lower paying jobs like city lifeguards, traffic employees, museum employees, custodians, social workers, and health care workers. The average District Council 37 member makes $29,000 a year, according to a union spokesperson.

"Many are raising families on this salary and having trouble making ends meet," said Lillian Roberts of District Council 37. "With transit hikes and higher taxes, everything has been raised but their salaries. We urgently need a fair contract now."

Union leaders also point out that when the mayor praises city government as being more efficient, it is the everyday workers that are making it happen.

COMPROMISES AND CHALLENGES

There have been some agreements that demonstrate that the mayor and the unions can negotiate when they want to.

In December, both sides reached an agreement on health benefits. City workers and retirees will now pay on average $200 more in out-of-pocket health expenses each year. In return, the city agreed to increase its contribution to a fund for cancer, asthma, and drugs.

Both sides called it a "win-win" agreement: the city saved $100 million and union members preserved their benefit packages. Labor leaders also said that it might be a major step in moving toward new contracts.

But as workers go longer without new contracts and raises, the tension between city government and unions grows.

In New York City, city workers are not legally able to strike, so protests, work slowdowns, and sick outs are options for disgruntled workers. These actions can translate into poorer performing schools, dirty streets, and eventually less money for city services.

It is often an election that gets the city and unions to sit down and negotiate.

Right now, many union leaders are faced with a dilemma: negotiate with the mayor or try to oust him in hopes of getting someone more sympathetic.

In a recent letter to members, Weingarten said that there was a "window of opportunity" to negotiate a new contract before Bloomberg's 2005 reelection campaign, but she said she has grown more pessimistic in recent weeks.

Mayor Bloomberg, who was elected without union support in 2001, has told labor leaders that he plans on being around for a while.

"Anybody that wants to bet that I'm not going to be around in two years and they'll wait it out, that's a pretty stupid bet, if you think about it," the mayor has said. "I'm going to get re-elected."

#####

RELATED ARTICLES

School Contracts: Do They Serve Students? (January 2003)

Police Pay: What Is Fair? (September 2002)

Labor and the New Workplace (June 2002)

Labor's Bill Comes Due(January 2001)

LINKS

City Office of Labor Relations

United Federation of Teachers

District Council 37

New York City Central Labor Council

New York City Police Benevolent Association

Uniformed Firefighters Association

New York Workers Need a Raise

All New Yorkers have had to brave record low temperatures, wind, snow, sleet and rain this winter. But for Joaquim Gonzalez and thousands of other delivery people throughout New York City the past several weeks have been particularly harsh. They have had to battle the cold, slush and ice for between seven and ten hours a day, six or seven days each week. And no matter how much Gonzalez works, he still cannot get ahead.

All New Yorkers have had to brave record low temperatures, wind, snow, sleet and rain this winter. But for Joaquim Gonzalez and thousands of other delivery people throughout New York City the past several weeks have been particularly harsh. They have had to battle the cold, slush and ice for between seven and ten hours a day, six or seven days each week. And no matter how much Gonzalez works, he still cannot get ahead.

He earns the minimum wage for tipped workers: $3.30 an hour. (Workers who do not have the opportunity for tips must be paid at least $5.15.) That means eight hours of biking around snowy, crowded Manhattan streets guarantees him a mere $26.40. Sometimes he lucks out and gets a few good tips. Other times he doesn't. Last month, Gonzalez rode his bicycle more than 70 blocks in the snow for a 50-cent tip. After paying for rent, food, subway, clothes, medicine, and maintenance of his bicycle, Gonzalez is left with almost nothing.

Gonzalez, like other minimum wage workers throughout New York State, is getting a raw deal. Unlike a growing number of states, New York has failed to take action to fix the problem of a stagnant and inadequate federal minimum wage by increasing the state minimum wage.

Since 1968, the purchasing power of the federal minimum wage has fallen by 40 percent. Throughout the 1960s and 70s, a full-time, year-round worker earning minimum wage could keep a family of three above the poverty line. Today, a full-time, year-round worker earning minimum wage can barely get his or her family three quarters of the way out of poverty.

Inflation has eroded the value of the dollar, and the minimum wage has failed to keep up. In the end, the New York State government is not all that different from the woman who tipped Gonzalez 50 cents. It is undervaluing its workers and doing the very least it can get away with.

Nationally, low-wage workers' real wages (taking inflation into account) increased by 5.5 percent between 1989 and 1999, but New York State's low-wage workers saw their real wages fall by 5.5 percent over the same period. Similarly, poverty declined in the United States during the 1990s, but it increased in New York State, as the income gap between rich and poor New Yorkers grew dramatically.

Governor George Pataki's proposed 2004-2005 executive budget does nothing to fix the problems of low-wage workers. In fact, Pataki's proposals would make the situation worse. The governor has proposed reducing food and living allowances for long-term welfare recipients, even though inflation continues to decimate the value of New York State's welfare grant.

Scapegoating the poorest of the poor, though, is nothing new. What is remarkable is that Governor Pataki's budget fails to reward work in any meaningful way. In fact, he has proposed a reduction in the amount of earned income that working welfare recipients can keep before losing benefits, thereby creating a disincentive to work. Additionally, his continued failure to increase New York State's minimum wage to keep up with inflation, and keep it pegged to inflation in the future, punishes hard-working New Yorkers.

New York is full of people who face rough labor conditions and the daily indignity of struggling to survive. Their treatment affects all of us. Poverty wages for workers translates into fewer consumers for business. When under-paid workers get sick, the government -- in other words, the taxpayer -- gets stuck with the bill.

New York's neighbors in Connecticut and Massachusetts have already raised their minimum wages to $6.90 and $6.75 per hour respectively, and neither state has experienced job losses as a result. Moreover, research done in California suggests that a higher minimum wage has important secondary benefits, such as improved health for low-wage workers and a greater likelihood that their children will graduate from high school.

It is high time for New York to join the growing number of states and the District of Columbia that have raised the minimum wage above the federal minimum of $5.15 per hour. Governor Pataki should support legislation currently pending in the State Assembly that would strengthen enforcement of minimum wage violations and raise the minimum wage by almost $2. This legislation would directly benefit more than 500,000 New Yorkers, and indirectly benefit many more, while saving the state money and giving the economy a boost. Joaquim Gonzalez, like all of New York State's minimum wage workers, deserves a raise.

Andrew Friedman is a senior fellow of the Drum Major Institute for Public Policy; Fernando Ferrer, former Bronx borough president and candidate for mayor, is president of the institute.

#####

Related Story:

A Minimum Wage Increase Will Hurt Small Business and the Working Poor

by Mark Alesse and Matthew Guilbault

A Budget With No Soul

Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s $45.7 billion preliminary budget(in pdf format) for fiscal year 2005 is a bland document, with few surprises and no soul. It lays out a generally optimistic budget-balancing scenario, but lacks any vision or sense of priorities. Revenues are up more than anticipated, enough so that there should be a $1.4 billion surplus by the end of the current 2004 fiscal year in June. This is a far cry from the emergency measures — mostly much higher taxes — that marked the mayor’s November 2002 and January 2003 budget plans. Last year’s bold policies worked and created an opportunity to make a personal mark this year.

But all we get is politics. A proposed $400 property tax rebate for each of the next three years for homeowners has already improved the mayor’s popularity in polls. Yet the mayor is oblivious to the new inequities the rebate would create in an already bizarre, unfair property tax system, particularly for renters and small businesses. And there is also a political slap at the City Council: The preliminary budget has no mention of over $200 million in cuts of essential service programs created by the council and borough presidents. It’s an old Rudy Giuliani trick — keeping the council busy restoring the missing dollars — that deflects council and public attention from new and more substantive options.

The budget has no soul because it has no message. Hundreds of pages of budget documents are now easily accessible in the office of management and budget’s vastly improved Web site. But the information has no overall policy or program context. Yes, the 311-system is up and running, and, yes, there is self-congratulation in changes in education, but mostly the documents simply add up to a lot of numbers. (The release two weeks after the budget plan of the preliminary mayor’s management report(in pdf format) -- the mandated report the mayor wanted voters to eliminate through last fall’s charter-revision ballot -- repeats the pattern; lots of data and no message.)

Gains in 2004 and 2005

The city financial plan for the next four years that accompanies the preliminary budget looks a lot better today than it did last June. Some improvement in the economy (but not in new jobs) has added $765 million to projected tax revenues for this fiscal year, and other revenues pushed the total new revenues over $1 billion. This helped increase the projected surplus for this year to $1.4 billion, which the new plan uses to ease budget gaps in 2005 and 2006. The 2005 plan also includes anticipated new state actions worth $400 million and federal actions worth $300 million.

The result of the revenue enhancements and the assumed state/federal actions is that there is little need to cut services next year. The mayor in this sense continues to keep his promise to maintain service levels. In fact, the annual exercise to save money, the Program to Eliminate the Gap (PEG), is only $324 million for 2005, or about one percent of total city revenues of $30.7 billion. (Whatever happened to productivity initiatives?) And most of the $324 million in savings comes not from service cuts, but from such actions as re-estimates of federal and state revenues (higher) and of anticipated needs and expenses (lower), shifting of costs from city to other government sources, and one-time revenues.

In this positive economic and fiscal context it is unfortunate that the mayor did not acknowledge his hidden budget cuts. The council, as reported in the January 22 Daily News, has found over $200 million in cuts that are not reported in the preliminary budget. They include:

- · $12 million in library cuts

- · $11 million in cultural affairs cuts

- · $11 million in senior service cuts

- · $9 million in child care service cuts

- · $8.5 million in mental health service cuts

In addition, city funding of youth services in the 2005 budget plan totals approximately $100 million, or some $40 million less than was adopted last June for the current fiscal year. The mayor disingenuously claims that all these reductions are not “cuts” because the programs initiated by the council and borough presidents are only one-year priorities, so that they were never in the 2005 plan to begin with. Mayor Bloomberg did not invent this petty political tactic, but he has certainly made it his own.

New Jobs

Although the mayor has little interest in expressing substantive goals in the budget, there are some interesting details buried in technical sections. For instance, job-creation prospects for the next four years are modestly positive: an estimated 40,000 new jobs in 2004, 51,000 in 2005, and an average 35,000 in the subsequent three years. The good news is that, unlike previous years, the city’s job recovery is not expected to lag behind the nation’s.

The recent recession had different effects on different job sectors. In a little more than two years after 2000, for instance, the high-salary securities industry went from 200,000 to 160,000 jobs. Finance-dependent services lost 70,000 jobs in roughly the same period. But there are growth areas in health, social, and education services, which collectively added 15,000 jobs in calendar 2003, and which are projected to add 15,000 more jobs each year through 2008. The securities and finance-dependent sectors are projected to have a much more modest recovery.

Empty Office Space

The budget plan also inadvertently raises some serious questions about the mayor’s sports-stadium plans. For instance, given the strong mayoral support for the New York Jets/office development on the West Side of Manhattan and the New Jersey/Brooklyn Nets basketball arena/office space in downtown Brooklyn --projects dependent on more than 30 million square feet of new office space -- it is interesting to note that two million (of nearly five million) square feet of recently completed office space in midtown Manhattan has yet to be leased. In addition, there is an unknown quantity of “shadow space,” office space currently leased but empty, so subject to future sub-leasing and therefore further depressing the market.

Prime market vacancy rates are projected to go over 13 percent in early 2004 and remain above 10 percent through 2006. Re-building the World Trade Center office space (15 million square feet lost) adds another warning sign. How do these utopian real estate goals justify any public budget support for sports stadium plans dependent on new office space for financing?

Rebates in Cigarette and Property Taxes

The budget’s casual approach to the equity implications of bold revenue plans is evident in two areas of the new budget. One is the latest report on the results of raising the cigarette tax from eight cents to $1.50 a pack. Big success! Sales in New York City have dropped by 47 percent, to 182 million packs in 2003, but revenues have grown from $27 million to $158 million in one year, an increase of $131 million, or almost 500 percent! Of course, the cigarette tax, like the sales tax in general, is a very regressive tax.

The proposed $400 rebate to owners of 1-, 2-, and 3-family houses, condos, and co-ops will cost the city about $250 million a year in lost revenues each of the next three years (a little more than the hidden service cuts). This will for the average owner apparently wipe out the 18.5 percent property tax rate increase imposed in November 2002 (which was compounded by increased assessments). This will help hundreds of thousands of owners, but it is a crude instrument.

The Independent Budget Office has over the years issued a series of reports that underscore the inequities in the city’s property tax system. One major problem is that renters’ tax burden is in effect five times that of house owners. Another is that co-op and condo owners have a higher property tax burden than house owners.

The council has narrowed the property tax inequities between house and coop/condo owners, but as in the mayor’s rebate plan, it has not tackled the larger problem of equalizing owner and renter inequities (beyond some marginal relief for seniors). Renters, who on average earn considerably less than owners, often do not recognize they are the big losers in such narrow and inequitable “reform,” and thus apparently pose little political danger to policymakers.

The re-constituting of the city’s tax revenue base by the cigarette tax and the property tax rebate should also be seen in the context of the budget plan’s phase-out of the one major progressive tax change during the Bloomberg administration. The revenue package adopted last June included two new, progressive personal income tax brackets for (joint) households earning over $150 thousand (4.25 percent) and $500 thousand (4.45 percent). But the plan also “sunsets” those progressive rates, reducing the 4.25 percent rate in the 2004 tax year, and eliminating both rates at the end of calendar 2005.

The City Council will hold hearings on the preliminary budget shortly (see the schedule) and will presumably hold separate hearings on the preliminary mayor’s management report, which the Speaker of the Council successfully urged voters to retain in the recent charter-revision vote. Perhaps there the public will get a chance to hear what message or vision the budget really carries. For the moment, the preliminary budget reflects silence and obfuscation.

Glenn Pasanen, former associate director of City Project, teaches political science at Lehman College of the City University.

A Field of Schemes

|

|||

| • Netting the Nets by Marty Markowitz | |||

| • Cheerleaders for Real Estate? by Tom Angotti | |||

|

|

While bringing the Nets to Brooklyn may sound like an intriguing idea, it has troubling fiscal, social, and economic implications for New York City as a whole.

THE MYTH OF JOBS, RECREATION, AND HOUSING

Typically, backers of a new stadium promise it will bring jobs, jobs and more, jobs.

Supporters of this stadium project have been hypnotized by similar claims. The reality is that Yankee stadium at 57,000 seats, which is double the size of the proposed stadium in Brooklyn, only offers 65 full-time positions. Any claim that this proposed stadium would provide for significant and permanent employment is a pipe dream.

Other supporters argue that local schools and other not-for-profit organizations will use the proposed stadium for their recreational events. I respond that there are a number of proposed capital projects to renovate armories and other buildings in Brooklyn into recreational facilities. These facilities, however, do not involve the condemnation of homes and or divert public dollars for private purposes.

The developer also claims that the 17 skyscrapers in his second phase will create 4,500 to 5,500 new apartments. That claim is the biggest joke of all.

Organizations involved with affordable housing do not build high-rise apartment buildings anymore. They realize that people want housing on a human scale where children can play in a yard and neighbors can look out for each other. Furthermore, the total cost for the purchase and construction of this project will in all likelihood make housing so costly, that most working families will not be in a position to afford to live there.

DISPLACING PEOPLE, CREATING TRAFFIC

The developer also plans to use eminent domain - the power to take private property for public use - to evict entire families and businesses for his project.

Approximately 1,000 men, women and children would be displaced if the stadium plans go through (we know the number because we counted - door to door). In addition to families being removed, blocks may be closed to accommodate the stadium separating Fort Greene and Clinton Hill from the Prospect Heights community.

The junction of Flatbush and Atlantic avenues is currently congested with traffic, and adding a stadium and 17 skyscrapers would only serve to worsen traffic conditions in a dense residential community. The massive influx of automobile traffic would tie up a main artery and create the biggest parking lot in the heart of downtown Brooklyn.

Imagine 23,000 more cars - that's nearly 1,000 more an hour - and many more children with asthma.

FINANCING THE FUTURE AWAY

The biggest gamble in all of this is the method of financing the stadium.

Recently, Ratner claimed that all he wanted in exchange for this project is for New York City to kick back some of the sales and income taxes to pay off loans that he had to borrow for the project. It was reported that the total bill for the stadium and surrounding commercial, office and residential development is being estimated at $2.5 billion (not including the $300 million that he would pay for the Nets).

This project will rely upon the use of Tax Increment Financing (TIF). Tax Increment Financing is one of the fastest growing development subsidies in the country, and it diverts future property, sales and income taxes in a designated district until a developer can pay off the costs of the project. It is just another name for corporate welfare.

Bruce Ratner's past is prologue to his future. His Atlantic Center Mall, which is directly across the street from the proposed stadium, is shrouded in a cloud of controversy. It has not resulted in any appreciable benefits to the community and has a 23-year property tax abatement with a disastrous private commercial rental history.

Not only will this be bad for Brooklyn, but for all of New York.

An Independent Budget Office report on the public financing of professional stadiums concluded that dedicating taxes for huge construction projects like this ties up a significant portion of the city's revenues, and often competes with funding for other city needs like schools, police, housing, playgrounds, and sanitation.

I was elected to protect and preserve working families, to create more affordable housing and employment opportunities, and to devise economic plans that involve and respect the character of local communities. I support development of this site, but development that make sense. We need projects that will generate revenue for the area and leave the Prospect Heights community intact.

We do not need to look like an imitation of Manhattan. We stand uniquely and proudly as Brooklynites.

Letitia James represents the district 35 neighborhoods of Prospect Heights, Fort Greene, Clinton Hill and North Crown Heights in the New York City Council.

#####

In This Series:

• Field of Schemes by Letitia James

• Netting the Nets by Marty Markowitz

• Cheerleaders for Real Estate? by Tom Angotti

Netting The Nets

|

|||

| • Netting the Nets by Marty Markowitz | |||

| • Cheerleaders for Real Estate? by Tom Angotti | |||

|

|

I am well aware of negative comments by some who live in the immediate vicinity of the proposed project. I know there are real concerns that must be addressed - and they will be. Netting the Nets must be a win-win for all of us who call Brooklyn home, and any project of this scale must have real community involvement to be successful.

The plan as presented so far is not perfect nor is it final.

That's why if the Nets are purchased and their move to Brooklyn is approved, I will be working with the community on a variety of issues, such as parking, traffic, and city services that must be addressed for this project to work.

But in my opinion the benefits of this project for all of Brooklyn greatly outweigh the arguments against it.

MASS TRANSIT TO THE GAME

Unfortunately, some of these comments in opposition are misleading, and others are simply less than accurate.

For example, referring to "20,000 extra cars," as if each and every man, woman and child would drive their own car to the game! Come on now, the reason why an arena works at this location is precisely because cars are not needed to access it.

Common sense, good urban planning, and care for the environment would tell you that the arena must be located where visitors have the best access by mass transit, and this location is Brooklyn's best for public transportation, with nine subway lines, four bus lines and the Long Island Rail Road all meeting there.

The irony is that if land were available to put an arena in another area of Brooklyn, as some have suggested, it would definitely result in the use of cars almost exclusively!

ENHANCING THE NEIGHBORHOOD, CREATING JOBS

Of course nothing would make me happier than if this project didn't take a single home or business, and I have urged flexibility in the plan to limit such action if possible. However, much of this project would be constructed almost completely over empty land - yes, empty space - over the Long Island Rail Road Tracks tracks, which is not exactly one of the garden spots in Brooklyn.

The project will also create a real wealth of jobs: from construction on the project, to working in the offices and retail stores, and the boost to local businesses who will sell to both tourists and new residents, all on top of the jobs working in the arena and the ancillary businesses (sound and light technicians maintenance, catering, cleaning, etc) at the arena itself and for specific events held there.

In fact, Andrew Zimbalist, one of America's leading opponents to urban stadiums and ballparks is a consultant on this project, and he supports it fully. We have learned from the past mistakes of new facilities - there is a right way and a wrong way to build.

And with a design by the world's leading architect, Frank Gehry, I am confident this will be an attraction and a landmark that will make us all proud.

The public's investment in the proposed arena would be rather modest for a project of this magnitude. The benefits and amenities it would provide - social and economic, short- and long-term - would be the most significant project accomplished in Brooklyn in decades, especially when you factor in the overwhelming demand in Brooklyn for affordable housing and jobs.

WORLD CLASS PROJECT

It comes down to this. I believe very strongly that all of Brooklyn would benefit from the return of national sports to our borough; an arena for world-class attractions and high school and college athletics; the construction of affordable and middle income housing, which is the number one need in every survey of Brooklyn residents; the development of office space for more employment and entrepreneurial opportunities for residents; and the tremendous number of jobs and economic activity that would result on Atlantic Avenue, Flatbush Avenue, Vanderbilt Avenue, Washington Avenue, and beyond.

I am confident that a national basketball franchise in Brooklyn will immediately become one of the country's best-loved teams.

As a result, this would draw new visitors to our borough and be a huge boost to Brooklyn's growing tourism industry. Brooklyn's need for an arena is perhaps just as important. Currently, we lack a large multi-purpose indoor space.

So in addition to a home for the Nets, an arena would allow Brooklyn to host college and high-school athletic events, graduations, trade shows, concerts, the kennel show, Ice Capades, conventions and numerous other events that we currently miss out on and that Brooklynites are forced to go to New Jersey, Long Island or even Manhattan to attend.

For all of these reasons and many more, I am an enthusiastic supporter.

At the same time, I understand the concerns, and on issues such as traffic and parking, they are real and need to be reviewed by experts with the participation of our community. Sadly, thus far the cry from some has not been "let's make this work," but rather, "let's stop this project totally."

Fortunately we live in a democracy that celebrates different opinions and encourages public debate. I look forward to such a debate and am confident that a successful win-win will result for the immediate neighborhood and for all of Brooklyn and New York City. I believe we can have both: an arena and a better neighborhood.

We can elevate Brooklyn to the national stage while enhancing the neighborhoods we love.

Marty Markowitz is the Brooklyn Borough President

#####

In This Series:

• Field of Schemes by Letitia James

• Netting the Nets by Marty Markowitz

• Cheerleaders for Real Estate? by Tom Angotti

Bush Tax Cuts and New York

President George W. Bush's tax cuts may well wind up the biggest legacy of the Bush administration. Their fiscal impact on the nation and New York has already reached startling proportions. For example, Citizens for Tax Justice, a research and advocacy group founded in Washington D.C. 25 years ago, estimates that the tax cuts, along with the massive borrowing needed to pay for the cuts and increased defense spending, will add $3.8 trillion to the national debt over six years. New York State's share of that new debt will be about $260 billion.

The tax benefits to individuals are huge -- over six years the country's taxpayers will receive over $1 trillion in tax cuts, with New Yorkers receiving about $78 billion of that. But the money goes disproportionately to the richest Americans, dramatically increasing an already large gap between the rich and non-rich in the nation and especially in New York.

Since the rich are less likely to spend their savings than lower-income Americans, the tax cuts will not stimulate the economy, according to the Citizens for Tax Justice. In addition, the new debt-related expenses and lost revenues will create major federal budget problems.

TAX CUTS AND THE $10 TRILLION PROBLEM

The Bush tax cuts began in 2001, with lowered federal tax rates and the expansion of several different tax benefits over 10 years. As the Tax Policy Centerrecounts, in 2003 Bush pushed through Congress a new round of tax cuts, introducing capital gains and dividend tax breaks. He also succeeded in accelerating several provisions of the 2001 tax cuts, such as tax rate reductions, marriage penalty relief, and the child tax credit.

It is the collective impact of these tax cuts that Citizens for Tax Justice traces for national and state impacts. The additional $3.8 trillion deficit by 2007 is just the beginning. In another study (in pdf format), Citizens for Tax Justice uses data from a Congressional Budget Office report to project an annual federal budget deficit of over $1 trillion a year by 2013.

That adds up to a tripling of the national debt a dozen years after George Bush took office, from $4.5 trillion to $14.1 trillion. Thus Bush would be accountable for almost $10 trillion in new debt. (These estimates are far higher than those by the Bush administration, because their assumptions are different. They assume, for example, that projected expenditure cuts won't happen, and that tax cuts will not "sunset.")

In the shorter term, according to Citizens for Tax Justice, the first four years of the Bush term will add up to $2.3 trillion in deficit spending, two-fifths of which is attributable to the tax cuts, and most of the rest to the "lousy economy."

NEW YORK BENEFITS AND BURDENS

Citizens for Tax Justice has analyzed both the benefit and burden of the Bush tax cuts. The New York data is statewide (although New York City is obviously a significant part of that data, both on the upper and lower ends of income).

Because the tax cut is entirely paid for by borrowing, the new debt burden becomes a significant problem - an average net burden of about $9,450 per person, or $37,826 for a family of four.

But it is the disproportion of the tax benefits in New York State that is most striking. New Yorkers in the top one percent of wealth (with an average income of more than $1.4 million) will get more than a third of the benefits this year, and more than half by 2007; they are promised an average tax savings of $81,308 this year. By contrast, the poorest 20 percent in the state will get less than one percent of the benefit; these poorest New Yorkers are promised an average tax savings of just $72 this year. The middle 20 percent (those with an average income of $35,000) are promised $793 this year.

While the wealthiest will get more and more, everybody else will get less and less. Citizens for Tax Justice points out that President Bush was misleading in saying of his 2003 round of tax cuts that it represented, "on average, a tax cut of $1,126" a year. Most New Yorkers will get far less:

· In 2003, 52 percent of New Yorkers will get less than $100.

· By 2006, 87 percent will get less than $100.

FEDERAL TAX CUTS OFFSET CITY AND STATE TAX INCREASES

Over the six-year period, there will nevertheless be an average of $13 billion of tax savings a year for New York State residents. Using New York State Department of Taxation and Finance datafor 1999 (latest available) we can make a rough estimate that some 40 percent of those savings will go to New York City residents.

(In 1999, nearly 40 percent of the total New York State adjusted gross income of $400 billion reported to the department was from New York City residents. And the 71,408 New York City taxpayers who reported income over $200,000 in 1999 represented 38 percent of all state taxpayers over that income level.)

One important result of these high-income federal tax savings is that they soften the impact of recent increases in city and state taxes, which are deductible on federal returns. In one example, in a July 2003 report(in pdf format), State Comptroller Alan Hevesi said the 2003 federal tax cuts alone would save city taxpayers approximately $3.2 billion. These savings would offset the impact of 2003 rate increases in state and city personal income taxes for married couples filing jointly with adjusted gross incomes over $200,000. Thus:

· Couples earning $200,000 had a net tax savings of $1,942.

· Couples earning $250,000 had a net tax savings of $3,152.

· Couples earning $600,000 had a net tax savings of $10,479.

FEDERAL DOMESTIC SPENDING STALLS

Bush tax cuts have not been offset by spending cuts. But the pressure on domestic spending is apparent in the current federal budget.

A new reportby the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities shows that over the past three years discretionary domestic spending, as well as defense, homeland security, and international spending have all increased - if at quite different rates. In fact, in the past year, domestic spending has stalled. Assuming that the Senate in January passes the omnibus spending bill passed by the House of Representatives in December:

· Defense, homeland security, and international affairs will show huge increases -- from $345 billion in 2001 to $534 billion in 2004.

· Domestic discretionary programs outside homeland security show small gains -- from $336 billion in 2001 to $389 billion.

However, domestic spending actually declined, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. When adjusted for inflation, the $389 billion planned for 2004 domestic spending is actually $7 billion less than in 2002, a decrease of two percent.

PUTTING EDUCATION, HOUSING, HEALTH, ETC. AT RISK

The Bush tax cuts, then, will transfer over $1 trillion over six years from the federal treasury to the nation's taxpayers, primarily to the wealthiest Americans. A substantial share of that transfer will go to wealthy New Yorkers and will offset to some degree recent state and city tax increases.

The huge tax revenue loss is compounded by the decision by the president and the Republican Congress to fund the tax cuts through borrowing. All this, plus a slumping economy and a huge increase in defense spending, adds up to nearly $4 trillion in federal budget deficits from 2002 to 2007.

Because of the Republican willingness to gamble on deficit spending to fund tax cuts and an expanding engagement in the Middle East, pressures to limit or cut domestic spending are likely to increase, an ominous prospect for a New York City whose economic recovery lags behind the nation's own slow recovery.

The real cut in federal domestic spending since 2002 is a disturbing sign that federal assistance for New York City in such areas as education, housing, transportation, the environment, health, and economic development is at risk because of the Bush tax cuts and other Republican priorities.

Glenn Pasanen, former associate director of City Project, teaches political science at Lehman College of the City University.

Artists' Fight To Sell On The Sidewalk

Ever since the founding of New Amsterdam, there have been battles over the right to control the public marketplace. The city's well-traveled sidewalks and parks offer enticing places to set up shop, whether you're selling books, art, knockoff purses, or hot dogs.

The most recent battle has been simmering since last March, when a 1991 New York State law that regulated vending expired. Since then, vendors have been proliferating in Times Square, Canal Street, Battery Park, and Fifth Avenue, with their numbers peaking during the holiday season. In October, the Times Square B.I.D. counted 208 vendors in the area, 66 more than in March. Mayor Bloomberg argues that the resulting sidewalk congestion creates a public safety issue, forcing pedestrians to spill out on to the street. This month, the State Assembly is likely to vote on legislation that would revise the old regulations and also place new restrictions on vending. Advocates for artist vendors say the proposed law infringes on their First Amendment rights and threatens their livelihood, and they have sworn to fight it.

Through odd legal quirks, the fate of artist vendors is tied to that of veterans. The old law limited the number of disabled veterans allowed to sell on city streets. Once it expired, veterans could sell anywhere and street artists could follow, thanks to a Department of Consumer Affairs policy that states once a disabled veteran sets up shop on an otherwise restricted street, artists can also set up there legally.

The legislation,which passed in the State Senate in June, would clarify regulations on veteran vendors, allow for fingerprinting of any vendor arrested for vending without a license, and prohibit vending altogether for several blocks around Ground Zero. The bill stalled when Democrats rejected the fingerprinting requirement, which they viewed as a threat to immigrant and minority rights (vendors would get permanent criminal records, even if their license had only recently expired). To its supporters, fingerprinting would be a security measure and a way to deter those without permits from selling. A related bill before the City Council proposes to create a permit system for vendors of written matter in all city parks, even though such a system was found to be unconstitutional in the past.before the City Council proposes to create a permit system for vendors of written matter in all city parks, even though such a system was found to be unconstitutional in the past.

Like immigrants, minorities, and disabled veterans, artist vendors tend to live near the poverty level and make their primary income on the street. While many hawk mass-produced prints of celebrities or landmarks, others sell original art that has not made it into museums or galleries. In the early 1990s, the city began requiring that artist vendors hold licenses, even though vendors of written matter did not need to do so. To protest this, a coalition of vendors formed A.R.T.I.S.T. (Artists' Response To Illegal State Tactics) and filed suit against the city. From 1996 to 2001, the group won a series of cases, including one that the city appealed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The courts found that vendors of paintings, sculpture, prints, and photographs have the same First Amendment rights to free expression as those who sell written matter. A 1996 ruling by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit found that “visual artwork is as wide ranging in its depiction of ideas, concepts, and emotions as any book, treatise, pamphlet or other writing, and is similarly entitled to full First Amendment protection. . . . The sale of protected materials is also protected. . . . Furthermore, street marketing is in fact a part of the message of appellants’ art. Anyone, not just the wealthy, should be able to view it and to buy it.” The courts did not extend First Amendment protections to vendors of crafts, such as jewelry and pottery, though this exemption is now facing legal challenges.

Today, A.R.T.I.S.T. has 1,000 members. The group’s president, the painter Robert Lederman, says that the push to control vending is being led by Business Improvement Districts, which, he believes, want to protect established business interests and clear sidewalks for their own use. He claims that the B.I.D.s want to take out franchises on “street furniture,” such as planters and garbage cans, on which to sell advertising. “There’s been a history of conflict between business interests and vendors,” Lederman says. “In the early part of the 20th century, the Fifth Avenue Association tried to remove Jewish vendors in front of stores. And in the â€40s Mayor LaGuardia tried to ban vending at a time when there were more vendors than stores, when almost anything could be bought on the streets.”

Some store owners have complained that vending takes business away from rent-paying stores. But there is also evidence that shoppers prefer areas where street life is bustling; one study found that businesses in the Caribbean neighborhood along Flatbush Avenue suffered after unlicensed street vending was shut down.

Lederman and other arts advocates argue that the city currently has enough tools to control vending, including regulations on how and where vendors can sell (20 feet from any storefront and 10 feet from a corner or subway entrance). In addition, the police can close any vending stand under “exigent circumstances,” including sidewalk congestion. According to a report by the Urban Justice Center, the Peddler Squad has become much more aggressive in giving out fines, closing down vendors, and confiscating goods for minor violations.

Jack Nesbitt, who has been selling his paintings on city sidewalks for seven years, was arrested twice last year. The second time, police brought him in for not having a permit (which he didn’t need), and then charged him with other violations, including being too close to a storefront. “They didn’t even pull out a tape measure when they arrested me. I had to take my own time to go to criminal court, where the sentences were dismissed,” Nesbitt says. “Free enterprise needs to start somewhere, and vendors are often the seeds.”

Martha Hostetter has written about the arts for the Village Voice, American Theater and Empire New York.

The City Modifies Its Budget and Searches for Cash

Every year around this time, the city charter requires the mayor to update the budget, called a budget modification. It was during last year’s modification that Mayor Michael Bloomberg unveiled an 18.5 percent increase in property taxes. This year, there is nothing so dramatic.

The good news is that the modification suggests at least a slight improvement in the city’s economy; it includes nearly $500 million more in projected non-property tax revenues. This news is supported by the City Comptroller’s December economic reportthat says, “The city is showing clear signs of economic recovery.” The city still lags behind the national recovery, and job losses continue, but the gross city product grew in the third quarter of calendar 2003 by 0.3 percent, after 10 quarters of decline.

The sobering news is that even after a $3.4 billion increase in tax revenues this year, revenues will be nearly $1.9 billion short as early as next year, and there is a projected budget deficit for 2007 of nearly $3.9 billion.

And so, there is a new search for new revenue once again.

THE 2004 MODIFICATION

This year’s budget, only five months old, jumps to $45 billion, some $1.3 billion more than projected in late June. In addition to the $500 million increase in non-property tax revenue projections, the modification recognizes federal and state categorical grants of another $600 million. Since they are given for specific purposes, these grants generally do not help in reducing budget deficits.

The city will use most of its new revenues in two ways: The budget stabilization account – a reserve fund where the city can park dollars – gets over $400 million (which at least in the current long-term plan will be used to reduce the budget deficits in the next two years). This is in addition to $300 million already in the general reserve fund, for a projected year-end surplus of over $700 million. Another $200 million will be used this year as pay-as-you-go capital expenditures. This has the advantage of reducing capital borrowing and thus reducing interest payments. The mayor plans to repeat this annual expenditure in the three subsequent years.

Total salary, wage, pension, and fringe-benefit costs of the city workforce are up a little over $200 million, to $24 billion, while other-than-personal service projected costs (including Medicaid, public assistance, and contractual human services) are up about $500 million since June, to nearly $19 billion. These modest changes seem again, at least in broad terms, to support the mayor’s claim that he has been able to keep services stable.

BEYOND THE 2004 BUDGET

The mayor and the City Council created a good part of future budget shortfalls by making this year’s increases in personal income and sales tax only temporary.

The mayor’s tax revenue strategy last year was bold but sudden, effective but undemocratic. Both the property tax increase in November 2002 and the personal income and sales tax increases in June 2003 were last-minute proposals that made public (and city council) engagement impossible. Thus it is no surprise that this November modification contains no information about future strategies.

Tolls On Bridges

The mayor’s first ambitious revenue idea – the introduction of tolls on the city’s bridges – was floated in the early months of his administration. Strong opposition to that idea and his current reluctance to follow-up perhaps help explain the secret revenue planning since. But the Independent Budget Office’s October 2003 report, “Bridge Tolls: Who Would Pay? And How Much?” is a good reminder of how important those revenues could be to attaining structural balance in the city’s long-term financial plan. The IBO estimates that the city could raise nearly $700 million a year by tolling the East River and Harlem River bridges.

One big objection to tolling bridges, of course, is that a majority of the drivers (55 percent) are New York City residents. The report speaks to that worry by noting (in an admittedly rough estimate, based on a household survey), “Exempting city residents from tolls would reduce the annual revenues to a combined $308 million.”

In terms of numbers of users, the report shows that fewer than 300,000 New Yorkers (out of 8 million) drive across these bridges, about 3.7 trips per 100 residents. In terms of income, about 42 percent of all users of the bridges are either low to moderate-income city residents (under $50,000 household) or middle-income city residents ($50,000 to $100,000). The report points out that although the number of New Yorkers affected would be few (and some would take alternative mass transit), the impact would be much more concentrated than in the case of personal income and sales taxes.

Stock Transfer Tax

Another IBO study, “Reviving the New York Stock Transfer Tax: Revenues and Risks,” speaks to another big revenue option that has been proposed by some advocacy organizations, including the Working Families Party and the Fiscal Policy Institute. The city first imposed a stock transfer tax in 1966. It was phased out by 1981. If still in place, it would have produced $9.3 billion in 2003 for the city. The study traces the impact of reviving the tax, at half its 1970s’ rate. That would produce nearly $5 billion, if there were no “adverse reactions.”

In a best-case scenario, the study finds that the new tax would increase transaction costs by 23 percent, reducing trading volume on the New York and American stock exchanges by 18 percent. That would eliminate nearly 60,000 private-sector jobs. Since the increased revenue would fund almost 38,000 public-sector jobs, the net job loss would be 22,000. That translates into a net revenue gain of $2.9 billion for the city. The study concludes with another scenario with “significant downside risks” – where one-third of trading activity moves out of the city – and job losses in the city “could climb to 150,000 and net city revenue gains would fall to zero.”

One-Shot Deals – 1. Airport Lease Agreement

Given the imminent reduction in basic tax rates and a reluctance to tackle controversial revenue sources like the city bridges and Wall Street, the mayor has become more dependent on one-shot deal-making. The apparent long-delayed agreement on a new airport lease agreement between the Port Authority -- announced by Governor Pataki and Mayor Bloomberg in October -- is the prime example. It is worth $700 million in up-front money over the next two years, and nearly $100 million a year thereafter.

While there seems to be general acceptance among fiscal monitors of this deal (former Mayor Rudy Giuliani failed during his two terms to settle disagreement over Port Authority payments to the city under the old agreement), a deal that ties the city until 2050 has received surprisingly little public attention or review. The deal is nevertheless a key to the current four-year financial plan.

One-Shot Deals – 2. Borrowing-for-Cash With Battery Park City Authority

Another quiet deal built into the current fiscal year budget is the city’s agreement with the Battery Park City Authority, controlled by the governor, to borrow $150 million through the authority, primarily to provide cash to the city. This requires state legislative approval and mimics a similar borrowing-for-cash that former Mayor David Dinkins employed through the authority in the early 1990s when in a fiscal bind. In both cases, the city in effect pays the debt service, through reductions in excess Battery Park City revenues that would otherwise come to the city. (A related if forgotten story is that excess authority revenues were supposed to be used for affordable housing.)

One-Shot Deals – 3. Snapple

The mayor has now moved from behind-the-scenes, public-authority deal-making for cash to corporate/city deals. The mayor’s agreement with Snapple to provide certain beverages to the public schools and other city facilities has roused the opposition of both the City Comptrollerand the City Council, which held a long hearing on the deal on December 4. The Comptroller, who testified at the hearing, objects to the process, and several Council members objected both to the process and the substance of the Snapple agreements described by Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff.

The Comptroller, in his remarks, said that the city “can’t cut corners” and “must be above reproach” in the procurement process. Doctoroff later contended that the deal was not subject to city procurement rules, that it was a unique opportunity for the city to develop a profitable relationship with a brand-friendly company. Several representatives from other beverage companies charged that the competitive process was flawed and at least two said had they known the full potential of the deal, they would have bid more than Snapple.